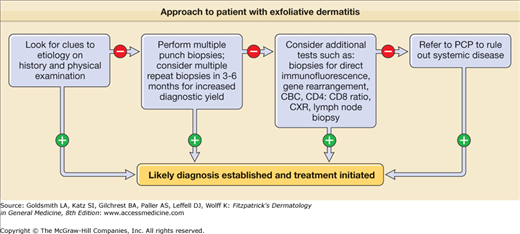

Exfoliative Dermatitis: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Several large studies have reported a widely varied incidence of exfoliative dermatitis (ED) ranging from 0.9 to 71.0 per 100,000 outpatients.1–4 A male predominance has been described, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1 to 4:1. Any age group can be affected, and with most studies excluding children, the average age of disease onset varies from 41 to 61. ED is a rare disease in children, and only little epidemiologic data is available for pediatric populations. One study found 17 patients, recorded over a 6-year period, with a mean age of onset of 3.3 years and a male-to-female ratio of 0.89:1.5 ED occurs in all races.6

A preexisting dermatosis plays a role in more than one-half of the cases of ED. Psoriasis is the most common underlying skin disease (almost one-fourth of the cases). In a recent study of severe psoriasis, ED was reported in 87 of 160 cases.7

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Establishing the etiology of ED can be challenging since it can be caused by a variety of cutaneous and systemic diseases (Table 23-1). A compilation of 18 published studies1,2,4,6,8–21 from various countries on ED shows that a preexisting dermatosis is the most frequent cause in adults (52% of ED cases; range, 27%–68%) followed by drug hypersensitivity reactions (15%), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) or Sézary syndrome (5%). No underlying etiology is identified in approximately 20% of ED cases (range, 7%–33%) and these cases are classified as idiopathic.

Dermatoses | Systemic | Infections | Malignancy | Congenital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Psoriasis is the most common underlying skin disease to cause ED (23% of cases), followed by spongiotic dermatitis (20%). Possible triggers for psoriatic ED include the following:

- Medications, such as lithium, terbinafine, and antimalarials

- Topical irritants including tars

- Systemic illness

- Discontinuation of potent topical or oral corticosteroids, methotrexate, or biologics (efalizumab)22,23

- Infection including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Pregnancy

- Emotional stress

- Phototherapy burns

Less common causes of ED in adults include immunobullous disease; connective tissue disease; infections, including scabies and dermatophytes; pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) (4% of dermatoses); and underlying malignancy. Even in patients with underlying dermatoses, it is critical to consider other possible etiologies. In one case series, malignancy-related ED was identified in seven patients, five of whom had a preexisting dermatosis.11 In about 5%–10% of idiopathic ED cases, erythrodermic CTCL was ultimately diagnosed.24 Solid organ malignancies as well as hematologic and reticuloendothelial malignancies may manifest as ED.

In neonates and infants, the differential diagnosis includes dermatoses (such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis), drugs, and infection (particularly staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome). In addition, several congenital disorders including the ichthyoses, both bullous and nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, Netherton syndrome, and immunodeficiencies should be considered (Box 23-1).

Most Likely

Consider

Always Rule Out

|

Topical and systemic medications are implicated in a significant percentage of ED cases (15%; range, 4%–39%) and the introduction of new drugs is likely to increase the incidence of ED. Both allopathic and naturopathic medications have been suggested to cause ED and the list is constantly expanding (Table 23-2). The most commonly implicated drugs include calcium channel blockers, antiepileptics, antibiotics (penicillin family, sulfonamides, vancomycin), allopurinol, gold, lithium, quinidine, cimetidine, and dapsone. However, most of the drugs are reported in single case reports. In addition to drugs, the contrast medium iodixanol (Visipaque) used during percutaneous coronary interventions has recently been reported to cause ED.25

Antibiotics |

Aztreonam |

Doxycycline123 |

Gentamicin136 |

Minocycline |

Neomycin |

Ribostamycin145 |

Rifampin |

Teicoplanin158 |

Thiacetazone2 |

Tobramycin163 |

Antivirals |

Dideoxyinosine171 |

Indinavir173 |

Interferon α 176 |

Zidovudine178 |

Antilepromatous |

Clofazimine183 |

Antifungals |

Nystatin197 |

Terbinafine201 |

Ketoconazole205 |

Griseofulvin207 |

Antiepileptics |

Lamotrigine214 |

Phenobarbital219 |

Aztreonam |

Anti-inflammatory |

Aspirin |

Celecoxib132 |

Diflunisal135 |

Metamizole137 |

Phenylbutazone2 |

Piroxicam140 |

Cardiac drugs |

Amiodarone143 |

Captopril146 |

Enalapril151 |

Isosorbide dinitrate12 |

Mexiletine |

Nifedipine159 |

Nitroglycerin161 |

Practolol1 |

Verapamil168 |

Chemotherapy |

Bevacizumab172 |

Carboplatin174 |

Cisplatin177 |

Denileukin diftitox179 |

Doxorubicin182 |

Fluorouracil |

Mitomycin C195 |

Pentostatin198 |

Vinca alkaloids202 |

Diabetic |

Sulfonylureas |

Chlorpropamide208 |

Psychiatric |

Barbiturates |

Bupropion217 |

Chlorpromazine1 |

Desipramine221 |

Escitalopram222 |

Etumine10 |

Fluoxetine224 |

Imipramine221 |

Lithium225 |

Phenothiazines |

Methylphenidate226 |

Aspirin |

Other |

Arsenicals |

Bacille Calmette-Guérin immunization138 |

Bromodeoxyuridine139 |

Cimetidine141 |

Clodronate142 |

Efalizumab147 |

Ephedrine150 |

Epoprostenol152 |

Ethylenediamine157 |

Fluindione160 |

Furosemide162 |

Homeopathic medicine (NatMur200)165 |

Hypericum (St. John’s wort)169 |

Interleukin 2170 |

Iodine14 |

Leflunomide175 |

Phenolphthalein14 |

Propolis184 |

Pseudoephedrine194 |

Ranitidine196 |

Roxatidine acetate hydrochloride206 |

Terbutaline12 |

Tetrachloroethylene14 |

Thiazide12 |

Timolol eye drops218 |

Tocilizumab220 |

Tramadol |

Tumor necrosis factor-α170 |

Valiya narayana223 |

Currently, the pathogenic mechanisms of ED have not been elucidated. It is not well understood how a preexisting dermatosis progresses to ED, an underlying disease manifests as ED, or the de novo ED develops. While the clinical presentation is similar in patients with diverse etiologies of ED, it is likely that different pathways lead to the common end result of skin-selective recruitment of inflammatory cells.

Cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors are believed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of ED. A study of cytokine profile in dermal infiltrates showed that there may be differences in pathophysiologic mechanisms between benign ED and Sézary syndrome—a T helper 1 cytokine profile was found in benign ED while a T helper 2 cytokine profile was found in Sézary syndrome.26 In a recent report, an overexpression of both T helper 1- and T helper 2-related chemokine receptors (CCR4, CCR5, and CXCR3) was found in ED of inflammatory origin, while a selective overexpression of CCR4 was found in Sézary syndrome,27 suggesting that Sézary syndrome is a T helper 2 disorder and that different pathways may contribute to skin homing of reactive lymphocytes in different etiologies of ED. Another study showed that Sézary syndrome and inflammatory ED are characterized by different memory T-cell subset expression, further suggesting different pathophysiologic mechanisms.28

The interaction between adhesion molecules and their ligands is important during inflammatory and immunological responses. Increased circulating levels of adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin) have been reported in benign reactive ED secondary to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis compared to controls.29 In contrast, no differences in expression levels of these molecules on endothelial cells were found in different types of ED, leading to the hypothesis that there are similarities in end-stage immunologic pathways in different types of ED.30

The complex interaction between adhesion molecules and cytokines likely contributes to the significantly increased mitotic and epidermal turnover rate in ED. The scaling of ED skin is a reflection of decreased transit time through the epidermis and leads to significant loss of protein, amino acids, and nucleic acids. Protein loss may increase by 25%–30% via scaling in psoriatic ED, and 10%–15% in nonpsoriatic ED.31 Additionally, protein-losing enteropathy may contribute to hypoalbuminemia.

Some patients with chronic idiopathic ED have been reported to develop CTCL that has led to concern that patients with chronic idiopathic ED may be at increased risk for progression to mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome.18,32 The chronic T-cell stimulation in these patients has been suggested to promote the development of CTCL.33–37 Recently, a premalignant or pre-Sézary-like condition has been described in elderly patients with chronic or relapsing ED without progression to hematologic malignancy characterized by a monoclonal expansion of CD4+CD7−CD26− lymphocytes.34 The term monoclonal T-cell dyscrasia of undetermined significance (MTUS), a T-cell equivalent to monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, has been proposed for this condition, which is believed to be probably benign.34 However, chronic idiopathic ED may also represent primary chronic, undiagnosed CTCL. Indeed, in up to 10% of idiopathic ED cases, erythrodermic CTCL is ultimately diagnosed.24

A role for immunoglobulin (Ig) E in ED has been proposed based on the observation of increased IgE levels in many types of ED. For example, it has been theorized that elevations in IgE in psoriatic ED may point to a change from a T helper 1 cytokine profile in psoriasis to a T helper 2 cytokine in psoriatic ED.38 This secondary mechanism is different than the primary overproduction of IgE in atopic dermatitis. Hyper-IgE syndrome is an immune deficiency that has been associated with ED, and has high IgE production due to selective insufficient interferon-γ secretion.39 The mechanisms related to this elevation of IgE may be related to the underlying disease process or to the manifestation of the disease as ED. Again, the mechanisms of IgE elevation appear to be different in different types of ED.

Recently, it has been theorized that Staphylococcus aureus colonization or another antigen, such as toxic shock syndrome toxin-1, may play a role in the pathogenesis of ED.40,41 Research on the immunopathogenesis of toxin-mediated infection demonstrates staphylococcal pathogenicity islands encoding superantigens (see Chapter 177). These islands carry the genes for the toxins of toxic shock syndrome and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome.42 83% of patients with ED were noted to have S. aureus colonization in the nares, while 17% had colonization in the skin; however, only one in six patients was S. aureus enterotoxin positive.41 (See Tables 23-1 and 23-2.)

Clinical Findings

A detailed history of a patient who presents with ED is an important tool for diagnosing the underlying etiology. The patients may have a history of dermatoses (psoriasis, atopic dermatitis) or a systemic medical condition. A thorough medication history should be elicited, including naturopathic and over the counter therapies. Patients with history of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis should be queried specifically regarding use of topical and systemic corticosteroids, methotrexate, and other systemic medications; topical irritants; systemic illness; infection; phototherapy burns; pregnancy; and emotional stress. ED patients commonly report thermoregulatory disturbances, malaise, fatigue, and pruritus; these symptoms are not specific to any etiology.

The onset of symptoms is important to assess different etiologies of ED. Primary skin diseases have a slower course while drug reactions usually have a rapid onset and resolution. One exception is ED associated with drug hypersensitivity reactions due to anticonvulsants, antibiotics, and allopurinol. This reaction develops in 2–5 weeks after medication is started and may remain ongoing after discontinuation of the medication. Associated signs of a possible drug etiology include fever, lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, edema, leukocytosis with eosinophilia, and liver and renal dysfunction.153,215

History and clinical presentation alone may not be sufficient to diagnose ED due to internal malignancy. Important clues for this diagnosis are an absence of prior skin disease, gradual onset, and a lack of response to standard therapies. A history of transplant should raise suspicion of CTCL, as it has been found that there is a higher frequency of ED secondary to CTCL in posttransplant patients.227

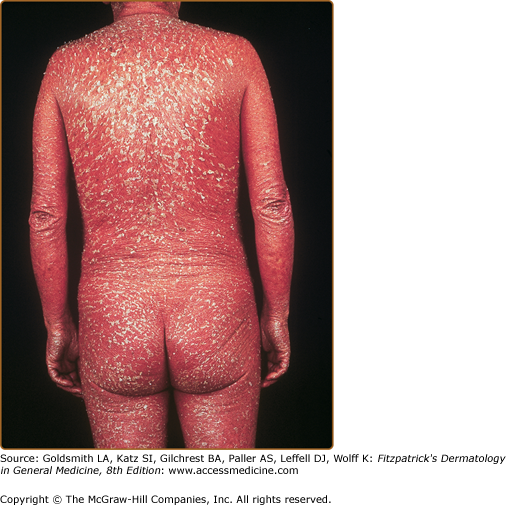

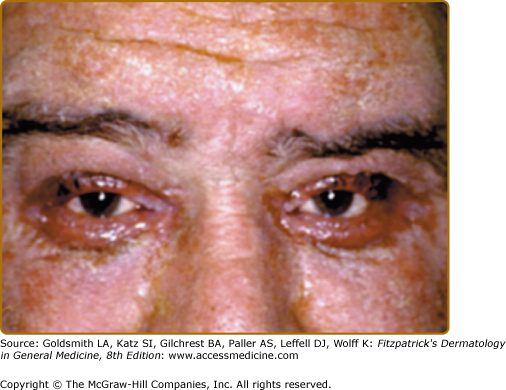

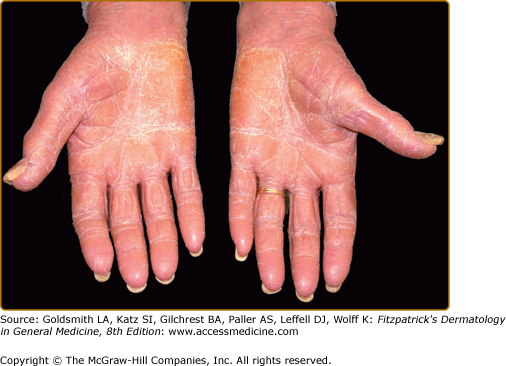

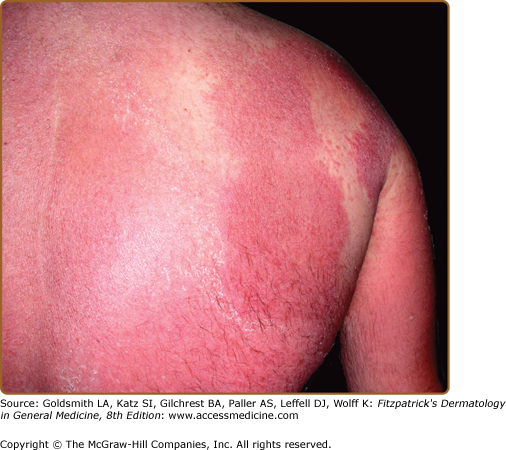

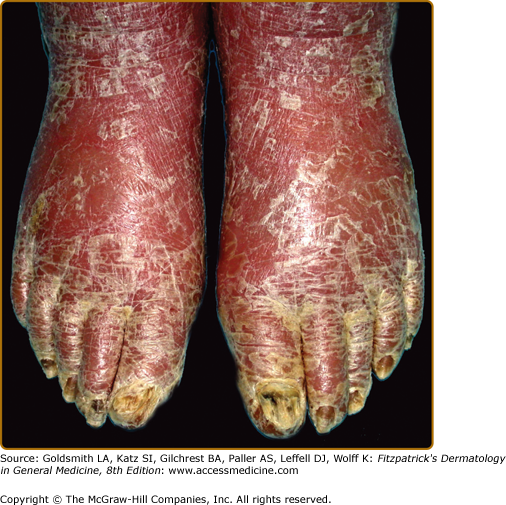

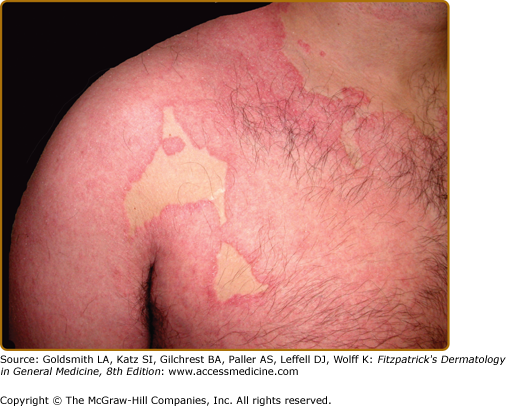

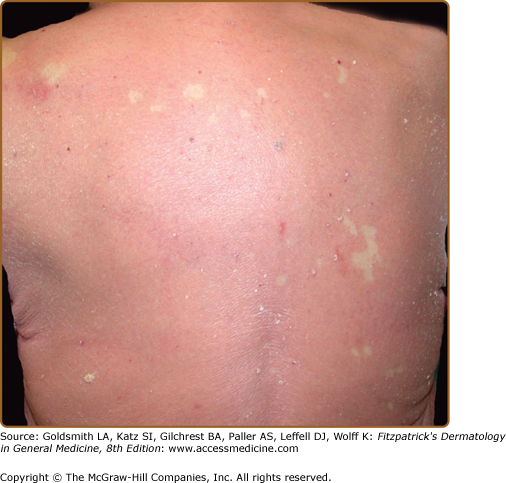

The classic presentation of ED is erythematous patches that increase in size and coalesce into generalized red erythema with a shiny appearance. By definition, ED involves more than 90% of the patient’s skin surface (Fig. 23-2). A few days after the onset of erythema, fine white or yellow scaling begins, classically arising in the flexures. Plate-like scaling may occur acutely and on the palms and soles. The scaling progresses further, giving the skin a dull red appearance. With chronicity, edema and lichenification lead to skin induration. Ectropion and epiphora may develop secondary to chronic periorbital involvement (Fig. 23-3). Palmoplantar keratoderma (Fig. 23-4) has been noted in up to 80% of patients with chronic ED.18

Some patients develop involvement of their hair and nails. Scaling of the scalp, alopecia, and in some cases, diffuse effluvium can be seen. Nail changes may include onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, splinter hemorrhages, paronychia, Beau’s lines, and, occasionally, onychomadesis.2 Shore-line nails with alternating bands of nail plate discontinuity represent drug-induced ED reflecting the periods of time the drug was used.228

Sparing of the nose and paranasal areas (the “nose sign”) has been described in some studies. Areolar sparing has been noted in some cases of CTCL, drug reactions, “eczema,” psoriasis, photosensitivity, and PRP.229 Typically, there is not mucosal involvement. Eruptive seborrheic keratoses may arise in patients with ED.230–232 The keratoses often resolve spontaneously as the ED subsides.

The cutaneous lesions may suggest the underlying etiology of ED. For example, in early psoriatic ED, classic psoriatic plaques may be seen. Gottron’s papules, heliotrope rash, and muscle weakness may be present in ED caused by dermatomyositis. Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji typically spares the abdominal skin folds (the “deck chair” sign).

Features of underlying diseases may aid in diagnosis (see Table 23-3 and eFigures 23-4.1, 23-4.2, 23-4.3, and 23-4.4).

Underlying Disease Process | Clinical Clues | |

|---|---|---|

Idiopathic erythroderma (“red man syndrome”) | Elderly men Chronic and relapsing course Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy | Pruritus Palmoplantar keratoderma |

Psoriasis (see Chapter 18) | History of localized disease Personal or family history of psoriasis Classic psoriasiform plaques on elbows, knees, sacrum, etc. Well-circumscribed plaques at margins of erythroderma (eFig. 23-4.3) | Large lamellar scales Psoriatic nail changes: pits, oil drop sign, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis Collarettes of scale suggestive of ruptured pustules of pustular psoriasis Psoriatic arthritis |

Atopic dermatitis (see Chapter 14) | History of localized disease, most often moderate to severe Personal or family history of atopy (atopic dermatitis, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis) Marked pruritus | Classic atopic lesions in antecubital and popliteal fossae Lichenification and prurigo nodularis Excoriations Focal skin atrophy from years of use of potent topical steroids |

Spongiotic dermatitis of other etiologies, such as contact dermatitis (see Chapter 13) (eFig. 23-4.1) or stasis dermatitis (see Chapter 174) | Distribution of original skin lesions History of contactant History of preexisting venous disease | |

Drug reaction (see Chapter 41) | Recent start of new drug, or use of frequently implicated drug Rapid onset of rash and progression to exfoliative Dermatitis | Lymphadenopathy Organomegaly Fever |

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (see Chapter 145) | Severe debilitating pruritus Fissured, painful keratoderma Hepatosplenomegaly | Lymphadenopathy Alopecia Leonine facies |

Immunobullous disease | ||

Pemphigus foliaceus and fogo selvagem (see Chapter 54) | Flaccid blisters Collarettes of scale at sites of previous blisters Superficial erosions and crusts | |

Bullous pemphigoid (see Chapter 56) | Tense blisters (early lesions) Deep erosions and superficial ulcers Urticarial plaques | Pruritus Elderly patient |

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (see Chapter 55) | Mucosal erosions and crusting prominent Rash resembles erythema multiforme Failure to thrive (i.e., cachexia) | |

Paraneoplastic ED | Failure to thrive (i.e., cachexia) | |

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (see Chapter 24) | Initial lesion: seborrheic dermatitis-like eruption of the scalp Worsening postsun exposure Generalized salmon-colored slightly infiltrated erythema (eFig. 23-4.4) | Islands of sparing (eFig. 23-4.4) Palmoplantar keratoderma, often orange (Fig. 23-4) Follicular pink papules of elbows, wrists, dorsal fingers or in skin spared from ED |

Chronic actinic dermatitis (see Chapter 91) | Photo-accentuation | |

Acute graft-versus-host disease (see Chapter 28) | History of bone marrow transplantation or blood transfusion | Initial lesion: palmar erythema Progression to toxic epidermal necrolysis |

Dermatomyositis (see Chapter 156) | Gottron papules Heliotrope sign Poikiloderma | Periungual telangiectasia Muscle weakness |

Sarcoidosis (see Chapter 152) | Apple jelly papules, plaques, and/or nodules | |

Norwegian scabies (see Chapter 208) | Down syndrome or nursing home patient Burrows | Massively thickened nails Keratoderma |

Related physical findings due to ED of any etiology may include the following:

- Tachycardia due to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss due to disrupted epidermal barrier.

- High-output cardiac failure has been infrequently reported secondary to the high-flow state in ED.233

- Thermoregulatory disturbances can result in hyperthermia or less commonly hypothermia; however, most patients complain of feeling chilly.

- Generalized lymphadenopathy occurs in more than one-third of patients.2,12,15 The clinician must distinguish between dermatopathic lymphadenopathy and lymphoma. If lymphadenopathy is prominent, a lymph node biopsy may be required.

- Hepatomegaly may occur in about one-third of patients 2,12,15 and is more commonly seen in drug-induced ED.

- Splenomegaly has also been rarely reported12 and is most commonly associated with lymphoma.

- Peripheral pedal or pretibial edema may occur in up to 54% of patients.15,32 Rarely, facial edema has been reported in drug-induced ED.

Laboratory tests are most often not diagnostic and not specific. Common laboratory abnormalities found in ED patients include anemia, leukocytosis, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, increased IgE, decreased serum albumin, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Fluid loss may lead to electrolyte abnormalities and abnormal renal function (elevated creatinine level). Elevated IgE levels have been noted in patients with ED unrelated to atopic dermatitis,10,12,18 including in 81.3% of psoriatic ED patients.38 Eosinophilia is nondiagnostic and has been found in 20% of ED patients.17 However, when highly elevated eosinophil counts are noted, the possibility of associated Hodgkin disease must be investigated.

It is very important to differentiate benign erythrodermic inflammatory diseases from Sézary syndrome. In cases where erythrodermic CTCL is suspected, a thorough evaluation of skin, blood, and lymph node samples is required for definitive diagnosis. Studies have shown that a level of 20% or more circulating Sézary cells is a useful diagnostic criterion for Sézary syndrome, whereas less than 10% is nonspecific.17,32 Exceptions do occur, such as in certain severe drug-induced reactions that can mimic Sézary syndrome (as hydantoin hypersensitivity).234 Several benign dermatoses, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, discoid lupus, lichen planus, and “parapsoriasis” show the presence of Sézary cells in numbers less than 10%.235 Demonstration of a clonal T cell receptor gene rearrangement is recommended for a sensitive and specific differentiation of Sézary syndrome from other etiologies of ED.

In a recent study, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis of the expression values of five genes [(1) STAT4, (2) GATA-3, (3) PLS3, (4) CD1D, and (5) TRAIL] has proven useful for molecular diagnosis of Sézary syndrome236

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree