Excision of Bone Tumors of the Knee

Raffi S. Avedian

DEFINITION

Bone tumors of the knee may be benign or malignant (bone sarcoma) and exhibit a variable natural history ranging from latent to rapid growth.

A bone tumor located in the distal femur or proximal tibia such that definitive treatment requires excision of part or all of the knee is discussed in this chapter.

Treatment for a bone tumor of the knee requires reconstruction of the knee articulation.

ANATOMY

The knee is the largest joint in the body. It is made up of the patellofemoral, lateral, and medial compartments.

Knee motion is primarily flexion and extension; however, bending and rotation are important components of knee kinematics.

The primary stabilizers of the knee are the extra-articular medial and lateral cruciate ligaments and intra-articular anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments.

The popliteal artery travels along the back of the knee and along with the tibial nerve travels between the lateral and medial head of the gastrocnemius. It branches into the posterior tibial artery, which travels deep to the soleus muscles; the anterior tibial artery, which passes from posterior to the anterior compartment distal to the tibia-fibula joint; and the peroneal artery, which branches off the tibiofibular trunk and is located medial to the fibula next to the flexor hallucis longus.

The geniculate vessels branch off from the popliteal vessels and are often all ligated during tumor resection of the distal femur.

The tibial nerve is located next to the popliteal vessels. The common peroneal nerve travels medial and deep to the biceps femoris muscle; a constant relationship that facilitates finding and protecting the nerve during tumor dissection.

PATHOGENESIS

The mechanism for bone tumor formation is not known.

Risk factors for sarcoma development include radiation exposure, radiotherapy, pesticide exposure, and hereditary conditions including Li-Fraumeni syndrome and retinoblastoma gene mutation.1

NATURAL HISTORY

Active benign tumors, such as giant cell tumor of bone, chondroblastoma, and aneurysmal bone cyst, will progress over time, may recur after excision, but are not lethal.

All bone sarcomas have the potential for local recurrence and metastasis.

Bones sarcomas have an estimated incidence of 3260 in the United States.

Lungs and other osseous sites are the most and second most common location of metastasis, respectively.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Pain is a common presenting symptom for aggressive bone tumors.

A thorough history and examination are important to assess duration of symptoms, comorbidities, physical dysfunction, organ involvement, overall health, and patient expectations in order to best tailor treatment strategy for the individual patient.

Neurovascular examination is mandatory for any extremity tumor.

IMAGING

Plain radiographs are used to formulate a differential diagnosis and a preoperative plan.

Magnetic resonance imaging is routinely used to determine extent of intramedullary tumor involvement, presence of soft tissue extension, status of the neurovascular structures, and presence of tumor within the joint space.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for a bone tumor includes benign tumors, sarcomas, lymphoma of bone, infection, and metabolic lesions (eg, hyperparathyroidism).

The most common bone sarcomas are osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The appropriate treatment for any musculoskeletal tumor is based on its diagnosis and natural history.

Biopsy incisions are considered contaminated and must be resected at the time of definitive surgery. Care should be taken to place the biopsy in a location that does not interfere with the final surgical plan.2

If a bone sarcoma extends into the knee joint space by direct growth, pathological fracture, or iatrogenic contamination, an extra-articular resection (keeping the knee joint closed) should be performed.

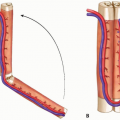

Reconstruction depends on the extent of bone excision and may include simple bone grafting, endoprosthetic implants, bulk allografts, osteoarticular implants, or vascularized fibula.

Preoperative Planning

A patient is considered ready for surgery after completion of staging and multidisciplinary review of pertinent imaging, pathology, and treatment strategy.

The surgical plan is created by thorough study of the preoperative radiographs and MR scan.

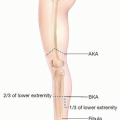

Bone cuts are planned by measuring on preoperative imaging the distance from an intraoperatively identifiable landmark (eg, femoral condyle, epicondyle) to the desired osteotomy site.

The soft tissue margin depends on the size and location of a soft tissue component to the tumor. For example, an anterior soft tissue mass long the distal femur can be safely resected by incorporating a portion of the vastus intermedius as the margin.

When tumor abuts but does not encase blood vessels or nerves, they can be dissected free by leaving adventitia and epineurium on the tumor as the margin.

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position; a hip bump may be placed if more lateral exposure is desired.

A sterile or nonsterile tourniquet may be used.

A leg holder may be used in cases where an endoprosthetic knee replacement is being performed.

Approach

The surgical approach varies based on location of the tumor.

The guiding principles for the approach to the knee in the setting of a bone sarcoma are to maintain a sufficient margin around the tumor and preserve as much normal tissue as possible without sacrificing cancer treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree