When and how did the wound begin?

Can any other precipitating event be associated with the onset of the wound?

Can any other precipitating event be associated with the onset of the wound?

• A walk in bare foot

• A fall

• A new pair of shoes

• An insect bite

• A surgical or invasive procedure

What kind of treatment has been used?

What kind of treatment has been used?

What other signs and symptoms are present?

What other signs and symptoms are present?

• Fever

• Itching

• Pain

Describe the pain. Quantify the pain. What alleviates the pain?

Describe the pain. Quantify the pain. What alleviates the pain?

Is the wound improving or regressing?

Is the wound improving or regressing?

What other disease processes are present?

What other disease processes are present?

What medications (with dosages) are being taken?

What medications (with dosages) are being taken?

• Prescription

• Herbal

• Over the counter

Are there any allergies relevant to the wound?

Are there any allergies relevant to the wound?

• Analgesics

• Antibiotics

• Adhesives

• Latex

What is the nutritional status?

What is the nutritional status?

• Are you a vegetarian or vegan?

• What did you have for dinner last night? For breakfast this morning?

What are the alcohol, tobacco, and drug habits?

What are the alcohol, tobacco, and drug habits?

What is the physical activity level?

What is the physical activity level?

What kind of assistive device is required for functional activities?

What kind of assistive device is required for functional activities?

What kind of shoes does the patient wear?

What kind of shoes does the patient wear?

If the patient is in an acute care or long-term care facility, a thorough chart review will also provide information that is helpful in directing the subjective interview, in determining the diagnosis, and in identifying the inhibiting factors. Chapter 11 provides a detailed discussion of inhibiting factors and includes a chart of laboratory values that are commonly abnormal for the patient with a wound. If, during the subjective evaluation, any of the signs and symptoms listed in TABLE 3-2 are observed or reported, the patient is advised to see the primary care physician or go to an emergency care facility. After the subjective evaluation is completed, the wound assessment is initiated.

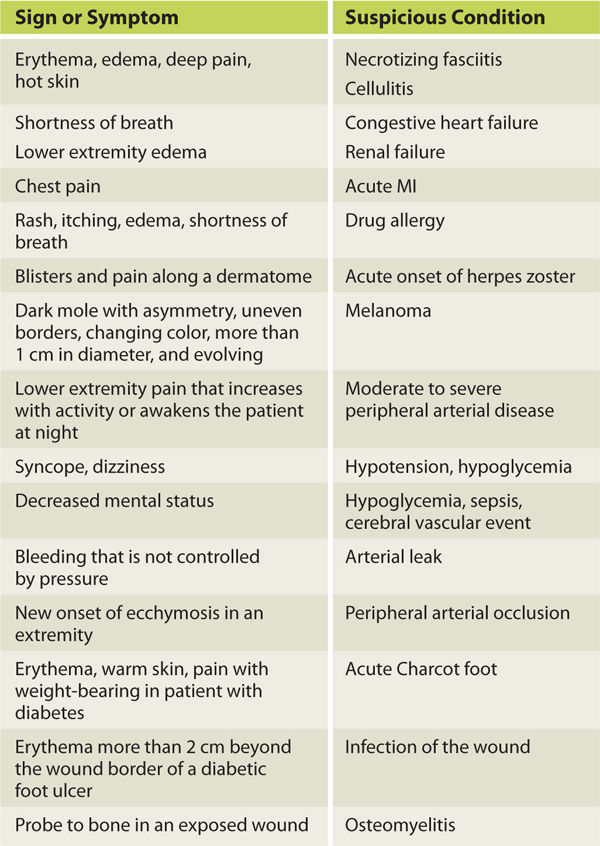

TABLE 3-2 Signs and Symptoms that Suggest a Patient Be Referred to a Primary Care Physician or an Emergency Care Facility

WOUND ASSESSMENT

In order to perform a complete wound assessment, good lighting and patient position for optimal visualization is recommended. Good patient position includes adequate support for the head and neck, covering for both modesty and comfort, and adequate exposure of the wound for both visualization and access. (FIGURES 3-1, 3-2)

FIGURE 3-1 Patient position in out-patient setting Patient with a left upper extremity wound is positioned with head slightly elevated and supported with pillows sufficient to accommodate any kyphosis; lower extremities elevated for edema reduction, access to wounds, and patient comfort; arm is supported on a table at a height that is comfortable for the shoulder. Having the hips and knees slightly bent is advised for older patients who may have low-back and leg pain due to spinal stenosis.

FIGURE 3–2 Patient position in in-patient setting Patient is positioned on the side for access to a sacral wound. A pillow between the legs prevents medial knee pressure and aligns the sacrum/low back for comfort. The patient is draped for warmth and for modesty.

Although the initial appearance of the wound and periwound skin is observed, the wound assessment is best completed after the wound is cleansed thoroughly with normal saline or sterile water and the wound base is exposed. The following substances are not advised for cleansing wounds,1 especially if there is exposed healthy tissue as in a traumatic injury:

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2): While diluted H2O2 may be useful for removing particulate debris, recent coagulum, and dried blood or debris at the wound edge, undiluted H2O2 is cytotoxic to clean or granulating tissue.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2): While diluted H2O2 may be useful for removing particulate debris, recent coagulum, and dried blood or debris at the wound edge, undiluted H2O2 is cytotoxic to clean or granulating tissue.

Ionic soaps and detergents: These cleansers (eg, pHisohex) can irritate tissue and increase the potential for infection if used on the wound surface.

Ionic soaps and detergents: These cleansers (eg, pHisohex) can irritate tissue and increase the potential for infection if used on the wound surface.

Iodine: 1% iodine is associated with decreased wound healing and has not been shown to decrease the risk of infection over normal saline (when cleansing a new, traumatic wound).

Iodine: 1% iodine is associated with decreased wound healing and has not been shown to decrease the risk of infection over normal saline (when cleansing a new, traumatic wound).

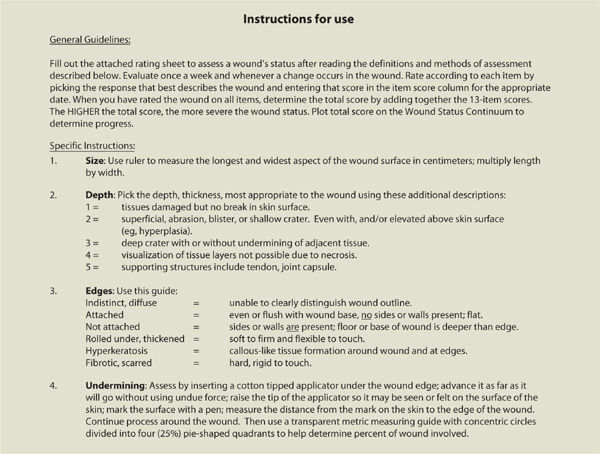

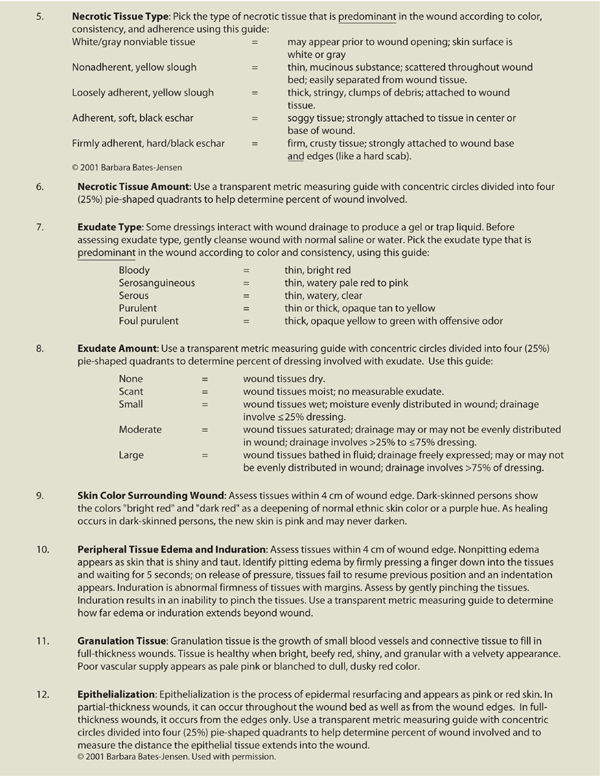

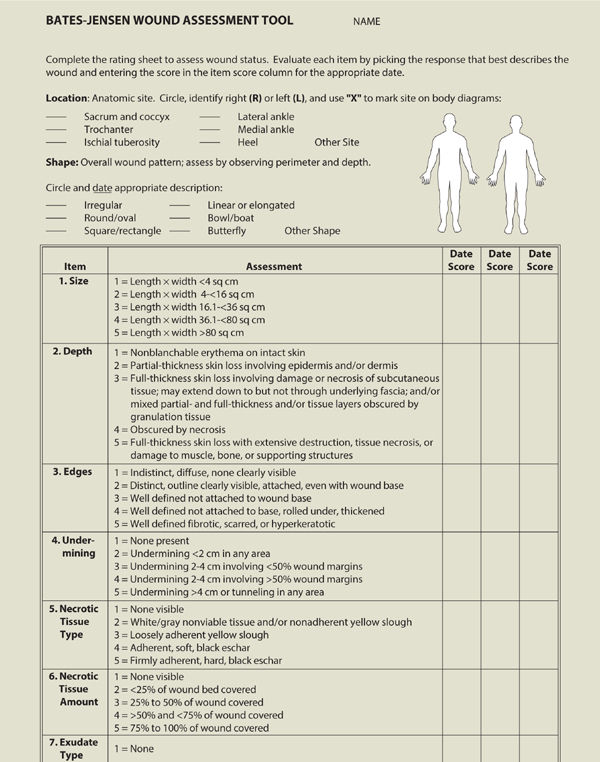

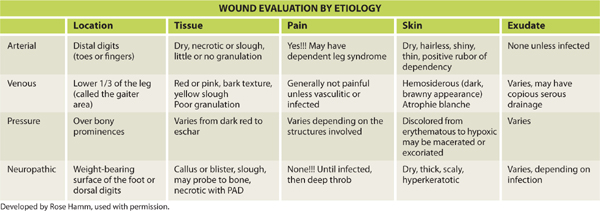

After cleansing, the wound and integumentary assessment includes location, size, tissue type, drainage, periwound skin color, edema, edges, odor, signs of infection, and pain. A standardized assessment tool such as the one developed by Barbara Bates-Jensen can be helpful in guiding the clinician through the assessment process and provides an objective total score and subsequent outcomes measures as the wound healing progresses, or can give an indication that the wound is deteriorating.2 (TABLE 3-3)

TABLE 3-3 Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool

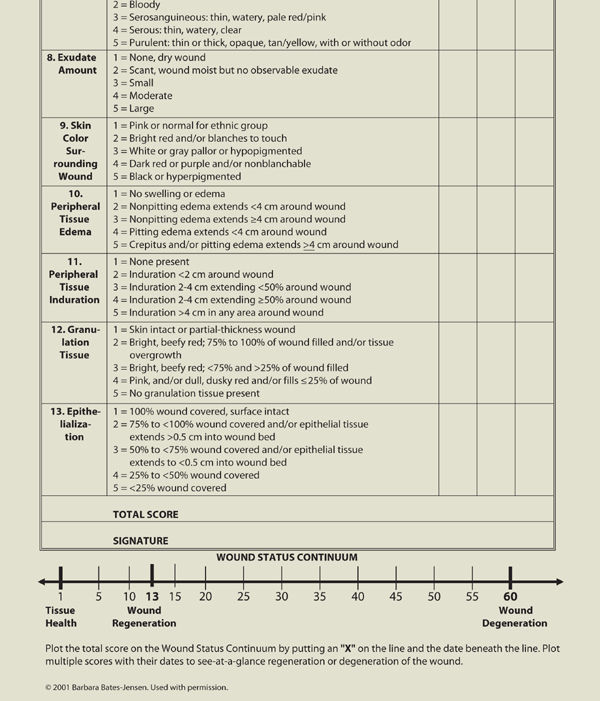

Another assessment tool is the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing, developed by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, which grades a wound based on length, width, exudate amount, and tissue type.3 This tool is described in more detail in Chapter 6, Pressure Ulcers. TABLE 3-4 provides a list of assessment tools intended to help the evaluator create an accurate picture of the wound status, assess pain associated with the wound, develop an effective and appropriate care plan, and document objectively the progression or regression of a wound.4 The literature provides several comparisons of the various tools used to assess wounds and/or predict risk for pressure ulcer development and the clinician is advised to select one that is most appropriate for the patient population being served.5,6 Use of an assessment tool is highly recommended for determining efficacy of interventions and reporting progress to third-party payers.

TABLE 3-4 Assessment Tools for Objective Wound Documentation

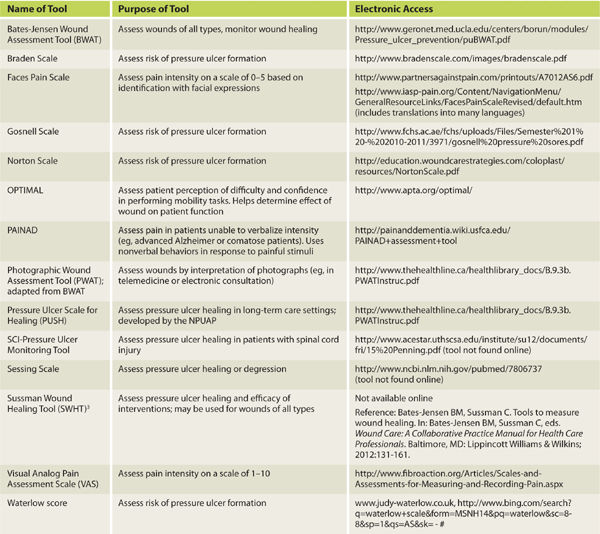

Location

Location is an important component of determining the wound etiology. TABLE 3-5 provides a summary of the characteristics of the four typical wound etiologies (arterial, venous, pressure, and neuropathic) and location differences are significant. Location is described by anatomical body part, using medical terms to define specifics. (FIGURES 3-3–3-6)

TABLE 3-5 Characteristics of the Four Typical Wound Etiologies

FIGURE 3-3 Location of wound on sacrum Wounds are located on A. left gluteal region, B. left sacral area, and C. right superior gluteal region.

FIGURE 3-4 Location of wound on the hand Wound located on the medial dorsal aspect of the right hand, including the web space, 2nd and 3rd proximal phalanxes.

FIGURE 3-5 Location of wound on lower extremity Wound located on the gaiter (or distal 1/3) area of the right lateral leg.

FIGURE 3-6 Location of wound on dorsal foot Wound located on the dorsal proximal interphalangeal joint of the right second toe.

Dimensions

Wound size is a major outcome measurement and is used to document improvement or lack of response to interventions, or to predict healing potential.7,8 For example, diabetic foot wounds that decrease in size during the first four to six weeks of healing are more likely to have full closure.9 Periodic measurements give objective feedback about the efficacy of treatment and serve as indicators as to when interventions need to be changed due to lack of tissue response. Wound dimensions are also one of the primary indicators used by third-party payers to determine treatment efficacy. Wound surface area can be calculated in several different ways; however, electronic assessment is the only method that is absolute.

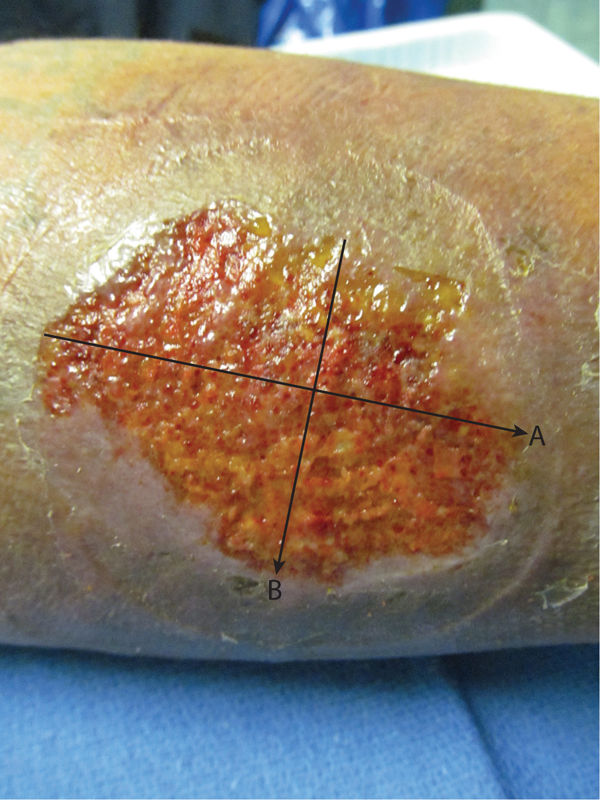

Perpendicular Method The perpendicular method measures the wound length at its longest dimension and the width at the longest dimension perpendicular to the length. (FIGURE 3-7) Measurements are recorded in either centimeters (cm) or millimeters (mm), and can be multiplied for a surface area, although it would be approximate because wounds are rarely shaped like a rectangle. The perpendicular method has been shown to have good reliability in wounds < 4cm2.10

FIGURE 3–7 Perpendicular method The perpendicular method measures the wound at the longest dimension (A) as the length, and the longest dimension perpendicular to the length (B) as the width.

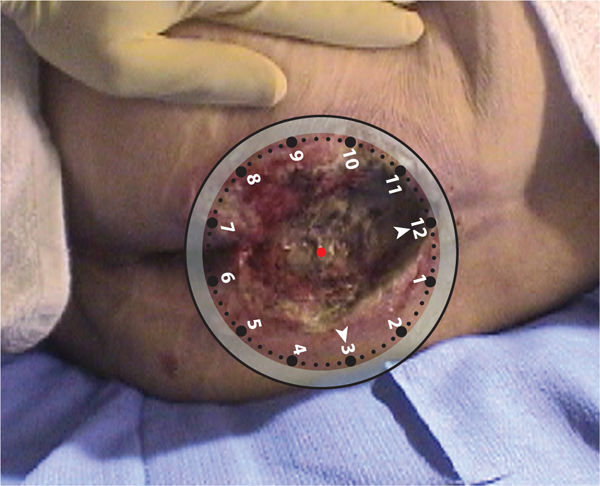

Clock Method The clock method imagines a clock superimposed on the wound with 12:00 placed cephalically and 6:00 placed caudally. Measurements are then taken at any direction on the clock and documented (eg, 6 cm at 12–6:00 and 2 cm at 3–9:00). (FIGURE 3-8) When using the clock method, which is beneficial for sacral ulcers, the position of the patient is also documented in order to have consistency of wound configuration between measurements. For example, if a patient is positioned in right side lying for measurements at the time of initial evaluation and in left side lying one week later for reassessment, the wound will have a different orientation and configuration, and measurements may not be as valid. The clock method is also helpful in describing wound landmarks (eg, undermining and sinuses) as illustrated in FIGURE 3-9.

FIGURE 3-8 Clock method for wound surface area The clock method is useful for aligning wounds with anatomical position in which 12:00 is cephalic and 6:00 is caudal, 3:00 is right lateral, and 9:00 is left lateral.

FIGURE 3–9 Clock method for location of sinus or undermining This incisional abdominal wound has a sinus at 12:00 or the superior aspect.

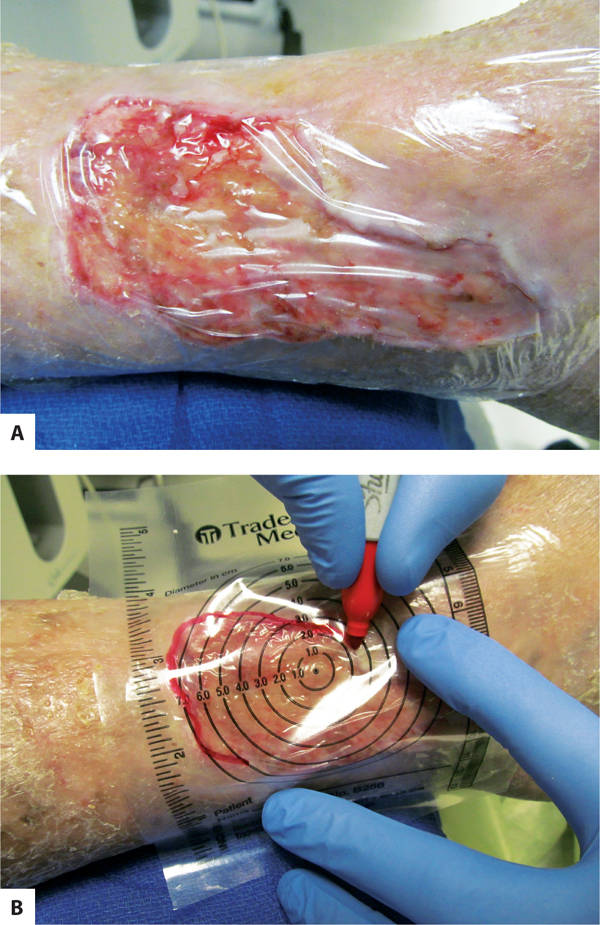

Tracing Tracing uses a clear plastic measuring guide over the wound to trace the edges and is useful for wounds that have serpentine or uneven edges. (FIGURE 3-10A, B) A clear film is placed over the wound first, and then the measuring guide, and the wound is traced with a permanent marking pen. Some guides have 1-cm grids that can be used to calculate surface area by counting the number of cross-sections or the number of blocks within the wound tracing.11 Tracing has also been combined with planimetry software to determine more accurate wound surface: the wound is manually traced, scanned into computer software, and exact surface area calculated.12

FIGURE 3–10 Tracing a wound A. Before placing the tracing guide on the wound, a clear plastic film is placed on the wound to prevent wound fluids and possible infection from being transferred to the patient chart. B. The tracing guide is placed over the first layer of plastic film and the wound is traced with an indelible marking pen. Tracing is recommended for serpentine wounds that do not have well-defined lengths and widths to measure.

Photography Digital photography has become the standard for wound photography due to its availability and its ability to be downloaded into electronic medical records. High resolution allows excellent visualization of wound characteristics. TABLE 3-6 lists some recommendations for achieving optimal results when using digital cameras. Some photographs also have the 1-cm grid described above to assist in calculating surface area.

TABLE 3-6 Guidelines for Obtaining Optimal Results When Taking Digital Photographs

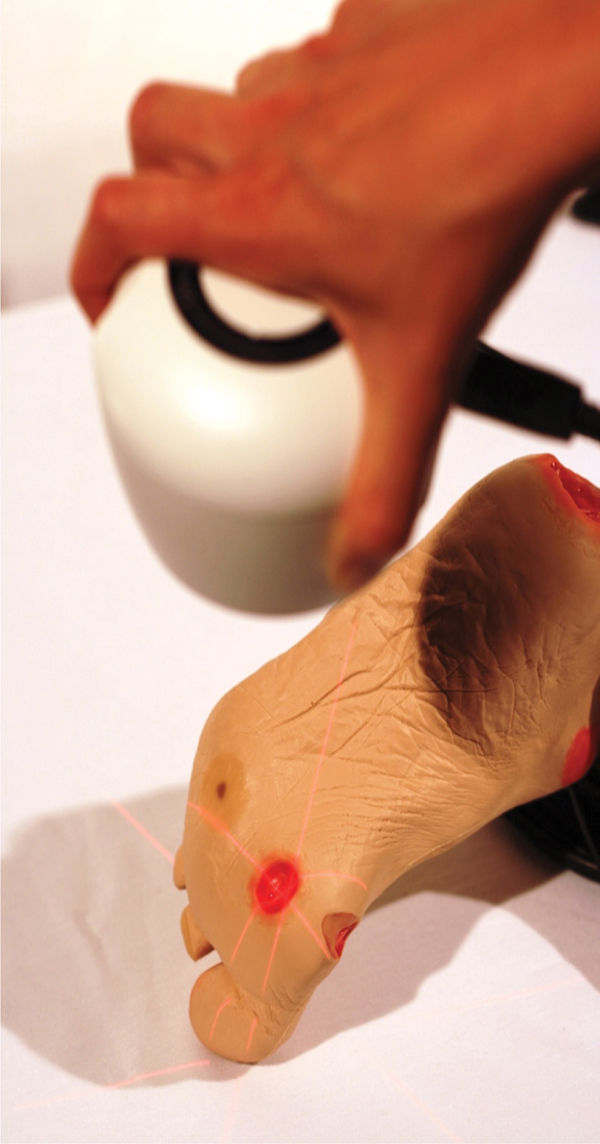

Planimetry Planimetry uses software to calculate dimensions from digital photography and has become the standard method for recording data for wound research. Results of surface area have been shown to be more accurate with planimetry, especially with wounds over 4 cm2.4 A typical system is composed of a digital camera that uses laser beams to ensure accurate focus on the wound, attachment from the camera to a personal computer, and software that allows the clinician to trace the wound bed and calculate the surface area.13 (See FIGURE 3-11)

FIGURE 3-11 Wound being photographed with Silhouette (point-of-care imaging device) The wound imaging, measuring, and documentation system uses laser intersections to focus the camera on the wound bed; transfers the image to computer software; and measures the surface area, depth, and volume electronically. The intersections of the laser lines on the wound are aligned so that they cross at the center of the wound, indicating the best focus and most accurate measuring. (Used with permission from ARANZ Medical Limited, New Zealand.)

Subcutaneous Extensions

Some wounds, especially pressure and diabetic foot wounds, tend to have necrotic subcutaneous tissue that prevents the wound edge from adhering to the wound bed. The author terms these subcutaneous extensions because the actual wound extends beneath the visible epithelial edge. Examples include undermining, sinuses, tunnels, and fistulas. Because the presence of subcutaneous extensions may be an indication of underlying infection or lead to deeper abscesses, documentation of measurement (in depth) and location (using the clock method of anatomic position) is an essential part of the assessment.3,14 Treatment plans need to include debridement, cleansing, and dressing application to subcutaneous extensions, as well as the visible wound bed.

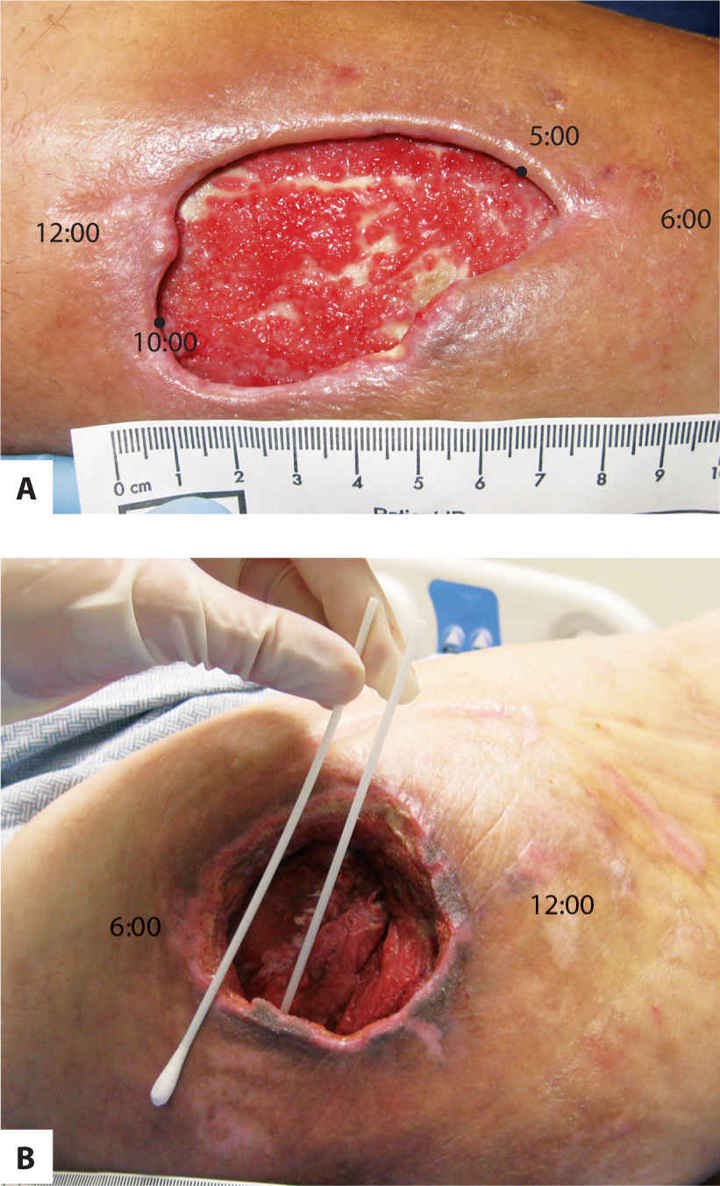

Undermining is a result of necrotic hypodermal connective tissue that disrupts the attachment of the skin to the underlying structures. Dark discolored skin around the visible periphery of the wound may be an indication of undermining and is explored with a sterile instrument to determine the extent. Documentation includes the depth at the deepest point and the extent using the clock orientation. (FIGURE 3-12A, B)

FIGURE 3-12 Undermining A. The shadow that extends across the left and upper borders of the wound indicates undermining where the skin is detached from the underlying structure, usually a result of autolysis of the subcutaneous tissue. The depth of undermining would be recorded, for example, as 3–5 mm from 10:00 to 5:00. B. Undermining is being measured in the pressure wound on a greater trochanter. The applicator on the outside indicates the depth of the undermining, which would be documented, for example, as 3.5 cm at 4:00.

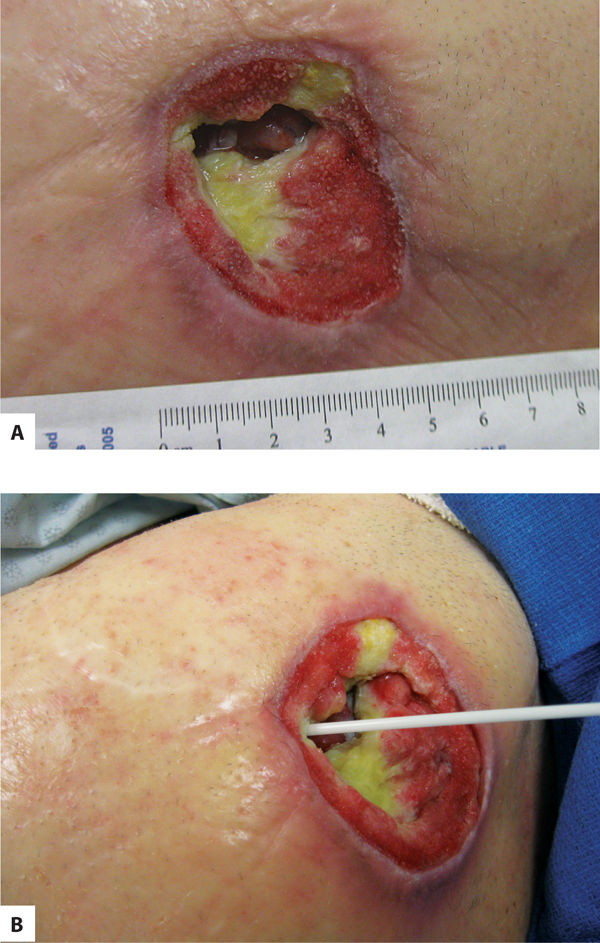

Sinuses are extensions that run along a fascial plane and usually have a small opening that connects to a deeper area of tissue loss. They may contain fluid trapped in the deeper area, and may lead to abscess formation if not explored and cleansed thoroughly. Suspicion of a sinus is indicated by a dark area at the edge of a wound, as indicated by the arrow. The depth is measured with a sterile alginate-tipped applicator and location recorded using the clock orientation. (FIGURE 3-13A, B)

FIGURE 3–13 Sinus A sinus or fascial track is indicated by the dark opening in the visible wound bed in photo A. In photo B, the sinus is being explored with a sterile applicator to determine the depth and possible pockets of fluid.

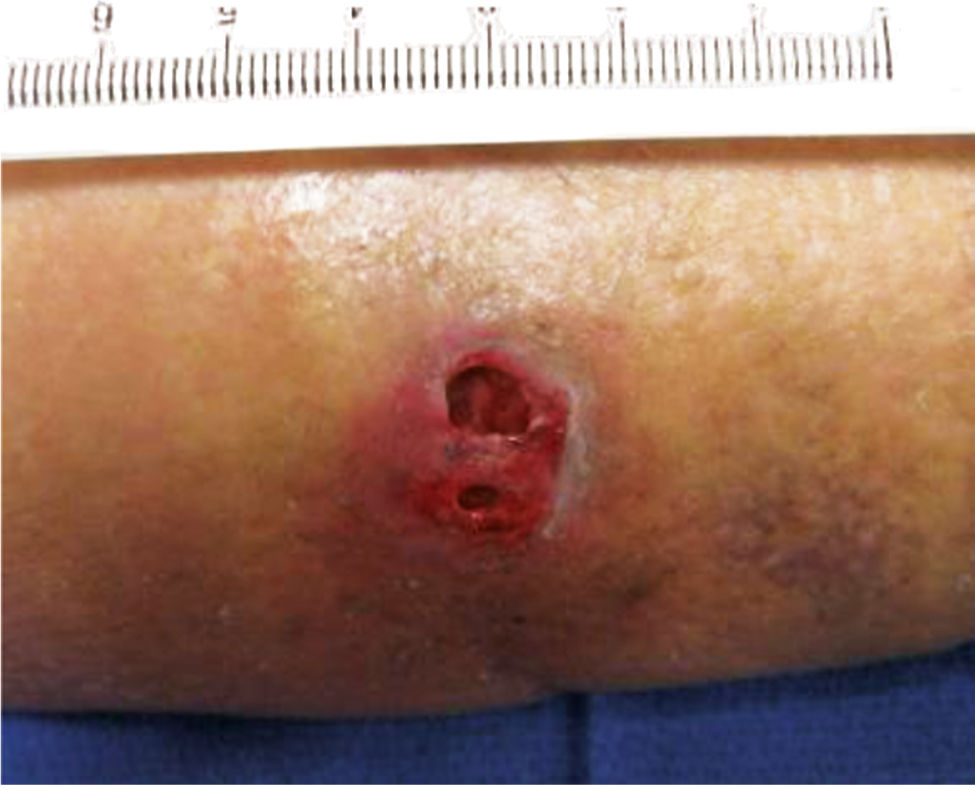

Tunneling occurs when two cutaneous wounds connect. (FIGURE 3-14) The two cutaneous wounds may initially appear to be two separate wounds, but when probed reveal that the subcutaneous tissue between the openings is necrotic and not connected to the under surface of the skin. In this case, the sizes of the two openings and the length of the tissue loss between the openings are measured and documented.

FIGURE 3–14 Tunneling A tunneling wound has two openings that are connected beneath the skin.

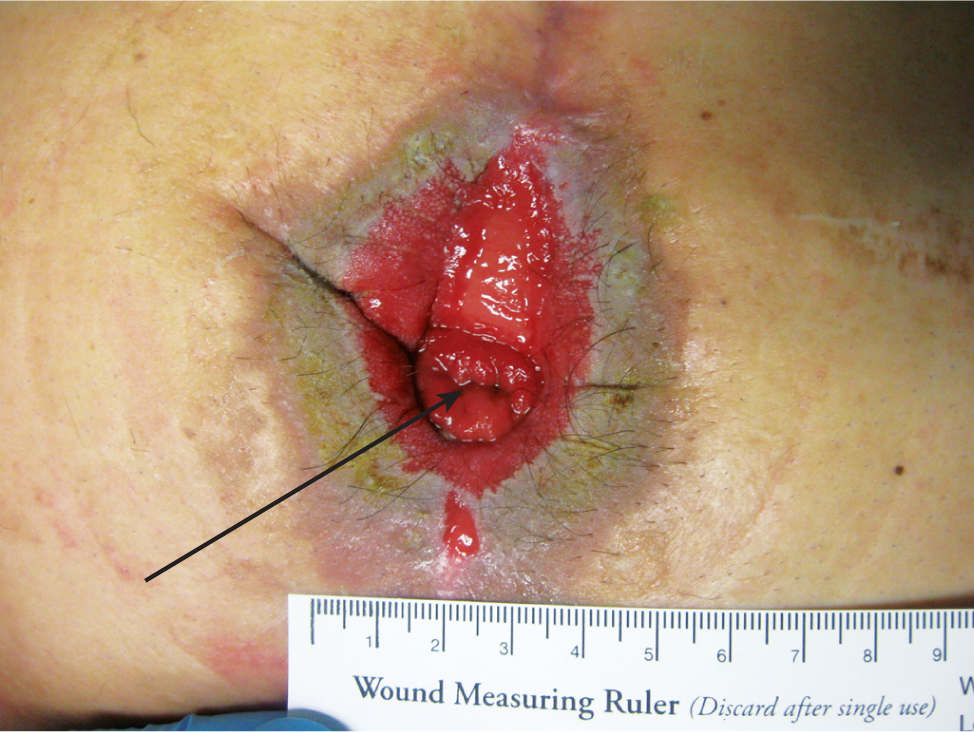

A fistula is defined as an abnormal connection between two epithelium-lined structures where a connection does not usually exist. Sometimes it is created for medical purposes, for example, in the case of an arteriovenous fistula between an upper extremity artery and vein for hemodialysis access. The type most frequently encountered in wound care is an enterocutaneous or enteroatmospheric fistula that connects some part of the digestive system with the skin or wound surface. (FIGURE 3-15) While the depth of the fistula is not appropriate to measure, the location is a component of the wound assessment. The type of drainage (eg, thin green, thick brown, or solid brown) can indicate the location of the digestive track where the fistula originates.

FIGURE 3-15 Fistula An enterocutaneous fistula is a connection between some part of the gastric system and the skin, often occurring after intestinal resection or gastric surgery. In this photo, the fistula is surrounded by a full-thickness wound, and the drainage that comes from the fistula can be caustic to the skin. When the fistula is surgically created, the everted part of the bowel is termed a stoma.

Tissue Type

Identification of the tissue type within a wound bed is necessary for understanding the phase of healing and for developing a plan of care, especially the optimal type of debridement and dressings. If one observes a structure that cannot be named or identified during the evaluation or treatment process, the procedure should be discontinued until research can help identify the tissue of concern. A documentation technique that is helpful in measuring outcomes is to assign a percentage of the total wound surface to each tissue type. While this is approximate at best, it does help document improvement in tissue quality as the wound progresses from inflammation to granulation to epithelialization. Normal structures (eg, bone, muscle, tendon, adipose) may be either viable or non-viable, healthy or not healthy, and are identified as such in the evaluation.

Eschar is nonviable or necrotic tissue that covers all or part of a wound base. It is composed of dead skin or subcutaneous cells and may vary in color (black, brown, gray, yellow, tan) and texture (hard, dry, rubbery, soft). Eschar is not synonymous with what is commonly called a “scab,” a result of blood and serum hardening over a fresh wound. (FIGURE 3-16)

FIGURE 3–16 Eschar The wound on the below-knee amputation site contains (A) hard dry black eschar and (B) softer brown eschar, both consisting of dead or necrotic tissue.

Slough is non-viable subcutaneous tissue, often found under eschar, and is a result of the body’s autolytic process to phagocytose dead cells. The usually soft and yellow substance has no real texture and is hard to grasp with forceps, unlike stringy, fibrous yellow or tan connective tissue that may also be under eschar. (FIGURE 3-17)

FIGURE 3–17 Slough The soft yellow substance on the wound surface is a result of autolysis of subcutaneous or connective tissue. Slough has no texture and is best removed with a curette.

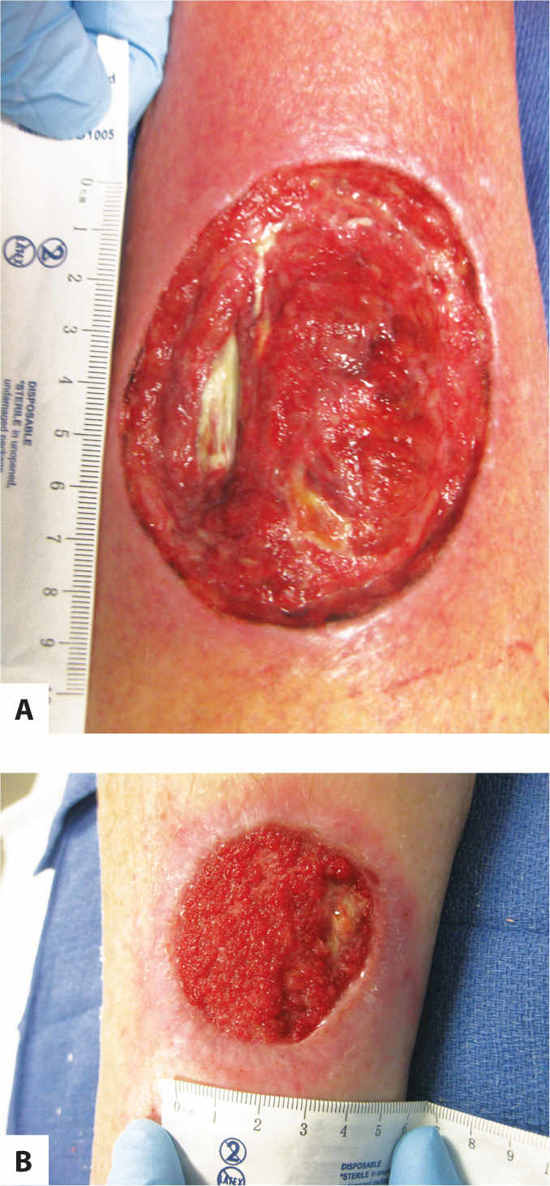

Granulation tissue, the hallmark of the proliferative healing phase, is composed of extracellular matrix and capillaries. It is the tissue that the body produces to fill in a wound cavity and has, as its name suggests, a granular appearance. Note that not all red tissue is granulation tissue; for example, muscle and subcutaneous tissue immediately after surgery may also be red but have a different texture. For this reason, describing wounds by color only (as is sometimes discussed in the literature) may be misleading in the documentation. (FIGURE 3-18A, B)

FIGURE 3–18 Granulation tissue Granulation tissue is composed of new capillaries in an extracellular matrix and has a granular, beefy red appearance, as seen in photo B (on the right). The subcutaneous tissue in photo A is also red, but has a different texture, indicating that it is not fully granulated. Photo A is transitioning from inflammation to proliferation; photo B is in the proliferative phase.

Muscle is identified by its location, its striated appearance, and its ability to contract with voluntary movement. In addition, healthy muscle bleeds when cut, is sensate and thus painful with stimulation, and is red. Conversely, unhealthy muscle is gray or brown, is insensate and therefore painless, does not bleed when cut, and has no contractibility. (FIGURE 3-19)

FIGURE 3–19 Unhealthy or non-viable muscle A. Unhealthy or non-viable muscle is dull gray or brown, is insensate and therefore does not cause pain when touched, does not bleed when cut, and does not twitch or respond to tactile stimulation. In addition, if the patient is asked to perform a joint movement, the non-viable muscle will not contract. Surgical removal is usually required for wound healing to progress. Non-viable muscle is observed in this fasciotomy wound at the time of initial evaluation. B. Three days later, the wound has started to granulate; however, non-viable muscle is still visible and requires further surgical debridement.

Bone is identified by its location and its hard texture when probed with a metal instrument. The color is tan when healthy, and black when necrotic. Usually bone is covered by periosteum, the bi-layer covering (composed of collagen and fibroblasts) of almost all bone, which contributes to bone repair and nutrition.15 (FIGURE 3-20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree