The pathologic evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes for melanoma metastases is not without significant challenges. It is affected by significant variation in approaches, which may compromise the final interpretation, leading to nonrepresentative spurious results. This article discusses various approaches along with recommended dos and don’ts for optimum evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes for melanoma metastases.

Many studies emphasize the role of sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy in the management of cutaneous melanoma. The pathologic evaluation of SLNs for melanoma metastases, however, is not without significant challenges. It is affected by significant variation in approaches, which may compromise the final interpretation, leading to nonrepresentative spurious results. Because of this, conclusions derived from most of the clinical trials and studies, based on older evaluation methods with older immunomarkers, may not be realistic. Some of the causes for concern include inadequate grossing/cutting of the SLNs, proportion of SLNs evaluated, selection of immunomarkers to detect the rare event of melanoma micrometastases, and application of some practices inadvertently compromising the final evaluation, such as frozen section analysis (FS).

The conventionally used melanoma immunomarkers, such as S-100 protein and HMB-45, have significant drawbacks when applied to evaluation of SLN for melanoma micrometastasis. MCW melanoma cocktail (MMC), a mixture of monoclonal antibodies to MART-1 {1:500}, Melan-A {1:100}, and tyrosinase {1:50}, has demonstrated an excellent discriminatory immunostaining pattern with significant advantages.

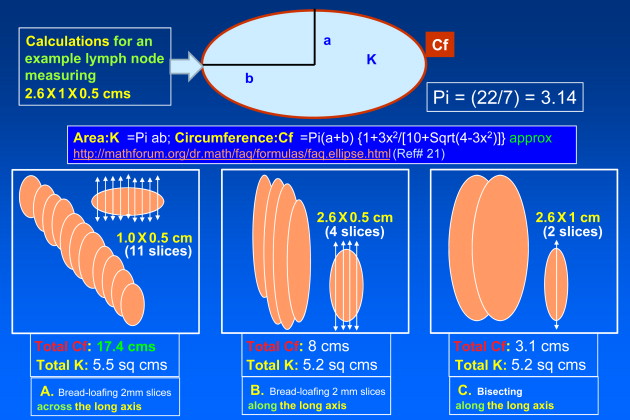

Melanoma metastases are located predominantly along the capsule of SLN and in the hilar area. Because of this, it is critical to evaluate a maximum portion of the subcapsular area. Transecting the lymph node perpendicular to the long axis and bread-loafing it into 2-mm thick sections achieves maximum exploration of this location.

Although the most precise approach would be to examine the entire SLN tissue, that is prohibitively expensive and unrealistic. Many studies have explored different approaches to address this issue with variable rates of detectability of melanoma metastases. Although evaluation of more levels increases the number of positive SLNs, the most practical approach is to evaluate three step levels at intervals of 200 μm. The section adjacent to the hematoxylin-eosin (H & E)–stained section at each level should be evaluated by immunostaining with optimum melanoma immunomarkers, such as MMC. All three levels may be immunostained simultaneously and evaluated. Alternatively, only the middle level is immunostained and evaluated initially, followed by immunostaining and evaluation of the other two levels if the middle level is negative. Or, all the three sections are evaluated together if they are small enough to be mounted on a single slide. An additional approach is to include SLN gamma counts in the algorithm with processing of SLNs proportionate to their level of gamma counts (examining more sections of hotter SLNs as compared with fewer sections for colder SLNs).

Because of its clean discriminatory immunostaining pattern in lymph nodes, MMC can also be applied for rapid intraoperative evaluation of SLNs for detection of melanoma micrometastases in imprint smears. In positive cases, this provides the opportunity to complete regional lymphadenectomy during the same surgical event and avoid additional surgical intervention at a later date. This article discusses these approaches along with recommended dos and don’ts for optimum evaluation of SLNs for melanoma metastases.

Perspective

General

Although the clinical relevance of SLN metastases is still evolving and not entirely understood, the status of SLNs is considered one of the most important prognostic factors in the management of cutaneous melanoma. Patients undergoing an immediate complete lymph node dissection after a positive sentinel node evaluation demonstrated a longer 5-year survival rate (72.3%), as compared with a statistically significant lower survival rate (52.4%) for those in whom the lymphadenectomy was delayed until the lymph nodes were clinically detectable.

Patients with morphologically positive SLNs may not progress to clinically widespread disease, so it is suggested that SLN biopsy may contribute to considerable biologic false positivity. Because individual tumor cells vary biologically, melanoma cells in a particular SLN may not have acquired the genotype to support their survival in distant sites. This concern is applicable, however, to many morphology-based scenarios in oncopathology.

Grossing of Sentinel Lymph Notes

It is usually recommended that a SLN is bisected along its long axis and submitted for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sectioning. Larger nodes are cut parallel to the meridian at 1-mm intervals. Melanoma metastases are located predominantly along the capsule and in the hilar area. Because of this, it is crucial to evaluate most of the subcapsular area of the SLNs.

As demonstrated by calculations and sketches in Fig. 1 , the total surface area evaluated by any cutting approach is not significantly affected, but the proportion of the circumference available for microscopic evaluation is markedly variable with different cutting methods. Bread-loafing the lymph nodes perpendicular to the long axis (see Fig. 1 A) explores maximum circumference, as compared with bisecting along the long axis (see Fig. 1 C) or bread-loafing along the long axis (see Fig. 1 B).

Identifying and Confirming Sentinel Lymph Node Status

Currently only a physician mapping the SLN and performing its biopsy can validate the sentinel status of the biopsied node. Pathologists may suggest the sentinel nature of the lymph node, if the node under evaluation is blue during grossing, but cannot confirm it objectively. Sentinel nodes may not be positive for metastases and other nonsentinel nodes may be positive for tumor cells. Because of this, presence or absence of metastasis cannot decide the sentinel node status.

To confirm the sentinel status of biopsied lymph node objectively, carbon particles have been included in the dye used for lymph node mapping. Identification of carbon particles in the lymph node during histomorphologic evaluation would allow confirmation of sentinel status of the biopsied lymph node. This approach, however, cannot be applied to cases where a carbon-based black tattoo is located in the same anatomic area as the primary melanoma, because it may share overlapping or identical lymphatic drainage. To avoid this challenge in the future, other colored nanoparticles may be used to replace carbon particles in the injected dye used for sentinel lymph node mapping.

How to and How Many Levels to Evaluate

Cases without grossly identifiable metastasis require the application of a more sensitive approach. If intraoperative evaluation is planned, FS should not be performed, to avoid introduction of freezing artifacts and significant loss of SLN tissue during FS procedure. These negatively affect the final morphologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. Multiple serial sections at different levels are evaluated with H&E stain and immunocytochemistry. The number of sections to be evaluated with H&E and immunohistochemistry is a nagging dilemma with variable approaches.

Immunohistochemical evaluation

Currently, morphologic examination with immunohistochemistry is the most reliable means of SLN evaluation, especially for the detection of melanoma micrometastases and for distinguishing them from benign nevus inclusions.

Conventionally applied immunomarkers for sentinel lymph node evaluation

Although S-100 protein and HMB-45 are excellent conventional melanoma immunomarkers, they can be ineffective in evaluation of SLNs for melanoma micrometastases.

S-100 protein (immunostain dendritic cells in the lymph nodes) and HMB-45 (immunostain mast cells) have a high noise-to-signal ratio in SLNs, with a less reliable interpretation than some of the recent melanoma immunomarkers, especially regarding melanoma micrometastases. Due to the previous biopsy procedure for the primary melanoma in the draining lymphatic field, reactive cells, including dendritic cells and mast cells, are relatively prominent in SLNs, further enhancing this noise factor.

Recent immunomarkers for evaluation of melanoma sentinal lymph nodes

Recently, MART-1, Melan-A, and tyrosinase were reported as melanoma immunomarkers without confounding immunostaining of different components in the reactive lymph nodes. A standardized cocktail can evaluate multiple epitopes and antigens in a single histologic section. This avoids challenges associated with evaluation of coordinate immunoreactivity for individual components in the cocktail in different sections. A mixture of these immunomarkers in the proportions standardized previously as MMC ( Table 1 ) showed an excellent discriminatory immunostaining pattern in lymph nodes, with improved detection and interpretation of melanoma cells ( Fig. 2 ).

| Melanoma Immuniomarker | Clone | Source | Concentration in the Final Cocktail a |

|---|---|---|---|

| MART-1 | M2-7C10 | Signet Laboratories (Dedham, Massachusetts) | 1:500 |

| Melan-A | A103 | Dako Corporation (Carpinteria, California) | 1:100 |

| Tyrosinase | T311 | Novocastra Laboratories (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) | 1:50 |

a To 9.68 mL of DAKO antibody diluent (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, California) add 20 μL MART-1, 100 μL Melan-A, and 200 μL tyrosinase.

Evaluation of other melanoma immunomarkers, such as HMB-45 and microphthalmia transcription factor, suggested that they would introduce nonspecificity if included in the cocktail. Although a cocktail of HMB-45 along with Melan-A and tyrosinase has been used in some studies, such cocktails have the potential for nonspecific immunostaining of certain cells in reactive lymph nodes (such as mast cells by HMB-45 component), and affect the final interpretation (especially in cases with scant tumor cells).

Although MMC is an excellent immunomarker for evaluation of melanoma micrometastases and covers a wider spectrum of melanoma epitopes and antigens than any single immunomarker (three epitopes in two antigens, Melan-A and MART-1, are two epitopes of the same antigen), it has a few relative limitations. Special variants of melanoma, such as desmoplastic melanoma and clear cell melanoma, are known to demonstrate variable immunoreactivity for different melanoma immunomarkers, including S-100 protein. This should not be a limiting concern because the diagnosis of melanoma is known at the time of SLN biopsy, and the purpose of evaluation of SLN is primarily to detect the metastases of a known melanoma. If the primary melanoma is a rare variant, the surgical pathology of the primary lesion should be evaluated for comparative review along with its immunoreactivity for MMC. If the primary melanoma is nonimmunoreactive for MMC, other melanoma immunomarkers (to which the primary tumor is immunoreactive) should be used with the caveat of accepting the limitations associated with that particular immunomarker. Usually, S-100 protein covers most melanomas and may be the immunomarker of choice in these rare situations, with a caution that the possibility of false positivity exists in interpreting scant micrometastases because of immunoreactivity of other nonmelanoma constituents, such as dendritic cells.

Immunohistochemical Evaluation of Sentinel Lymph Nodes for Melanoma Micrometastases in Paraffin-Embedded Tissue Sections

The details of the protocol for immunostaining 3-μm–thick, paraffin-embedded, tissue sections with MMC were reported previously. Applicable to most of the melanoma markers, MMC also immunostains benign capsular nevi (BCN) in 4% to 10% of SLNs (in addition to melanoma cells).

Distinguishing BCN from melanoma metastases is one of the most significant diagnostic challenges during evaluation of melanoma SLNs. Currently, morphologic evaluation, with some assistance from immunochemistry, is the only approach to distinguish them. BCNs are generally nonimmunoreactive or weakly immunoreactive for HMB-45, and it has been suggested as an immunomarker to differentiate capsular nevi from melanoma micrometastases. Several melanomas are also nonimmunoreactive for HMB-45. A strong immunoreactivity for HMB-45 favors melanoma metastases and may rule out capsular nevus. Nonimmunoreactivity for HMB-45, however, does not equate with BCN.

Thus, morphology is the most reliable distinguishing feature. BCN are usually seen as cohesive groups of spindle shaped benign melanocytes, mostly along the capsule, and have been reported in variable numbers, ranging from 4% to 22 % of lymph nodes.

This challenge is enhanced further by the observation that singly scattered MART-1 or Melan-A immunoreactive parenchymal cells may be observed even in lymph nodes from nonmelanoma cases. One study reported such cells in 11 lymph nodes (two lymph nodes also had associated BCN, four lymph nodes from same case with squamous cell carcinoma) out of 217 lymph nodes from nonmelanoma cases. Because of this reason, non–in situ molecular methodologies, such as reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction, without morphologic input are not adequate for separating out BCN from melanoma metastases. Nonmorphology-based molecular tests alone have higher false-positive results, introducing significant nonspecificity, so are not reliable.

Although the immunohistochemical features (discussed previously) may be considered, morphology is an important primary tool for correct interpretation of capsular melanocytic nevi in the current situation. Cytologic atypia along with location in the subcapsular sinus favors micrometastases. Scant isolated cells with MART-1 or Melan-A immunoreactivity in melanoma SLNs without associated cytologic atypia, comparable to that of the primary melanoma lesion in H&E stained sections, should be interpreted with caution. This highlights the crucial role of morphology in SLN work-up with caution regarding nonmorphology based molecular tests.

Immunohistochemical evaluation

Currently, morphologic examination with immunohistochemistry is the most reliable means of SLN evaluation, especially for the detection of melanoma micrometastases and for distinguishing them from benign nevus inclusions.

Conventionally applied immunomarkers for sentinel lymph node evaluation

Although S-100 protein and HMB-45 are excellent conventional melanoma immunomarkers, they can be ineffective in evaluation of SLNs for melanoma micrometastases.

S-100 protein (immunostain dendritic cells in the lymph nodes) and HMB-45 (immunostain mast cells) have a high noise-to-signal ratio in SLNs, with a less reliable interpretation than some of the recent melanoma immunomarkers, especially regarding melanoma micrometastases. Due to the previous biopsy procedure for the primary melanoma in the draining lymphatic field, reactive cells, including dendritic cells and mast cells, are relatively prominent in SLNs, further enhancing this noise factor.

Recent immunomarkers for evaluation of melanoma sentinal lymph nodes

Recently, MART-1, Melan-A, and tyrosinase were reported as melanoma immunomarkers without confounding immunostaining of different components in the reactive lymph nodes. A standardized cocktail can evaluate multiple epitopes and antigens in a single histologic section. This avoids challenges associated with evaluation of coordinate immunoreactivity for individual components in the cocktail in different sections. A mixture of these immunomarkers in the proportions standardized previously as MMC ( Table 1 ) showed an excellent discriminatory immunostaining pattern in lymph nodes, with improved detection and interpretation of melanoma cells ( Fig. 2 ).

| Melanoma Immuniomarker | Clone | Source | Concentration in the Final Cocktail a |

|---|---|---|---|

| MART-1 | M2-7C10 | Signet Laboratories (Dedham, Massachusetts) | 1:500 |

| Melan-A | A103 | Dako Corporation (Carpinteria, California) | 1:100 |

| Tyrosinase | T311 | Novocastra Laboratories (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) | 1:50 |

a To 9.68 mL of DAKO antibody diluent (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, California) add 20 μL MART-1, 100 μL Melan-A, and 200 μL tyrosinase.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree