CHAPTER 8 Evaluation and Treatment of the Patient with Ptosis

Anatomy and function

Normal eyelid position

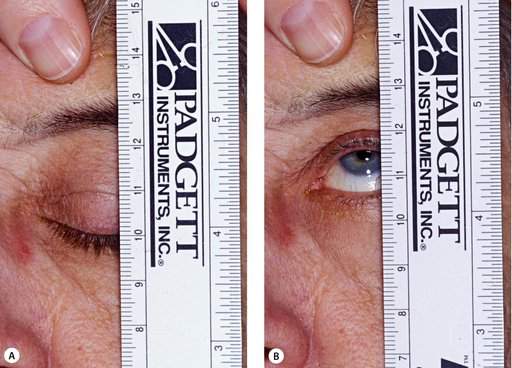

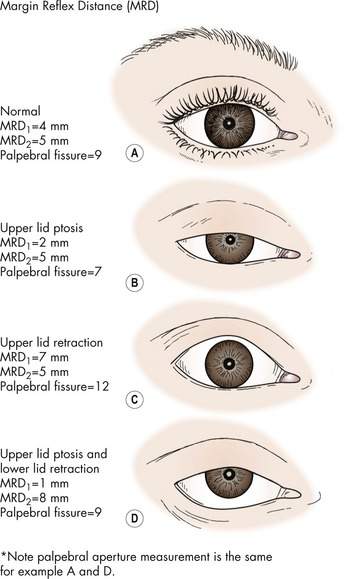

The upper lid rests at or just below the upper limbus. The lower lid normally sits at the lower limbus. The palpebral aperture is the distance between the upper lid margin and the lower lid margin. The normal measurement is approximately 9 mm. The position of the upper lid is best quantified as the upper lid margin reflex distance (MRD1). This measurement extends from the central corneal light reflex to the upper lid margin and is normally 4–5 mm (Figure 8-1).

The upper eyelid retractors

The retractors open the upper eyelid. The retractors are:

Functional or anatomic abnormalities in the levator muscle complex are the cause of most ptosis.

The levator muscle

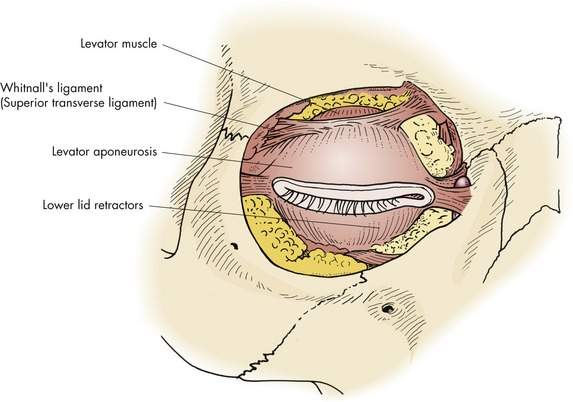

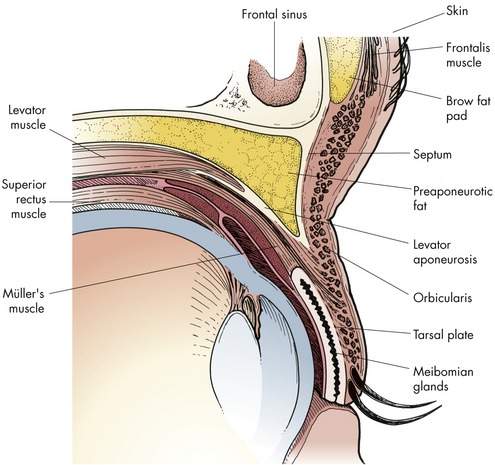

The levator muscle is the primary retractor of the upper eyelid. This skeletal muscle is responsible for voluntary elevation of the upper eyelid. Innervation to the levator muscle is via the superior division of the third cranial nerve (the oculomotor nerve). The levator muscle originates at the orbital apex and extends forward inferior to the bone of the orbital roof (Figure 8-2). At the orbital aperture, the levator is supported by Whitnall’s ligament (see Figure 2-22). As the levator muscle travels anteriorly, it becomes a fibrous aponeurosis that extends inferiorly into the eyelid to insert on the anterior aspect of the tarsal plate. Fibrous extensions of the aponeurosis pass through the orbicularis muscle to create the upper eyelid skin crease (Figure 8-3).

Müller’s muscle

Müller’s muscle is responsible for the involuntary upper eyelid elevation seen in the sympathetically innervated “fight or flight” phenomenon. Müller’s muscle is “sandwiched” between the conjunctiva posteriorly and the levator aponeurosis anteriorly. Müller’s muscle extends from the superior margin of the upper tarsal plate to the level of Whitnall’s ligament (Figure 8-3). A prominent surgical landmark on the surface of Müller’s muscle is the peripheral arcade, a vascular arcade extending across the muscle a few millimeters above the tarsal plate (Figure 8-4; see also Figure 2-23). You will recall that the loss of innervation to Müller’s muscle results in the mild ptosis associated with Horner’s syndrome.

The frontalis muscle

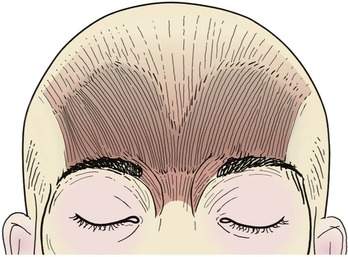

No doubt you have patients with drooping upper lids who lift their eyebrows to provide a tiny bit more upper eyelid elevation. The frontalis muscle lifts the brows and is a weak retractor of the upper eyelids (Figure 8-5). The frontalis muscle is part of the galea aponeurotica of the scalp. The fibrous aponeurosis extending from the occiput becomes the frontalis muscle inferior to the hairline. Like the other muscles of facial expression, the frontalis muscle is innervated by a branch of the facial nerve, the frontal nerve (see Figure 2-27). Elevation of the eyebrows and prominent forehead furrows seen in a patient with ptosis tell you that the drooping lids are interfering with the patient’s vision. In some patients, a brow ache will occur with extended brow activity. The action of the frontalis muscle should be “blocked” with your thumb when making measurements of the eyelids.

The “eyelid vital signs”

The condition or “health” of the eyelid can be identified by measuring the eyelid vital signs:

We have already mentioned the MRD as a simple way to measure the height of the upper lid. The most practical measure of the strength of the levator muscle is the levator function. The levator function is defined as the excursion of the upper lid from extreme downgaze to extreme upgaze measured in millimeters. This movement is normally 15 mm. You will recall that the upper eyelid skin crease is created by the pull of the levator aponeurosis on the skin. The skin crease height is the distance from the lid margin to the crease. This height varies among individuals, but averages 6–8 mm for men and 8–10 mm for women at the highest point. The crease slopes both medially and laterally. A weak levator muscle creates less pull on the skin so the crease is less distinct or “weak.” Read this paragraph again.

• Simple congenital ptosis is associated with decreased levator function

• Involutional ptosis is associated with normal levator function

• If levator function is normal, a shortening of the aponeurosis works well to lift the upper lid (a levator aponeurosis advancement operation)

• If the levator function is poor, the eyelid is surgically “connected” to the brow (a frontalis sling operation). The action of the frontalis muscle lifts the upper eyelid

Notice how important the levator function is. As you become experienced in taking care of patients with ptosis, you will see that asking “What is the levator function?” becomes the critical question (Box 8-1). We will discuss this further in the next section.

Box 8-1 The “Eyelid Vital Signs”

The upper lid skin crease is formed by the pulling of the levator aponeurosis from beneath skin:

• The position and strength of the upper lid skin crease help in recognizing the amount of levator function present and the type of ptosis

• In involutional ptosis, the crease is high and pulls diffusely

• In simple congenital ptosis, the crease is not well defined and there is reduced pull

• Proper placement of the crease during surgery is important for symmetry and an optimal surgical result

Classification of ptosis

A simplified system

There are many types of ptosis and many systems that classify the types (Box 8-2). From a practical point of view, most patients you will see have either simple congenital ptosis or involutional ptosis. Most of the children you will see have simple congenital ptosis. Most of the older adults you will see have an involutional ptosis. I group the other less common types into the category unusual ptosis. This is an oversimplification, but it works well.

The levator function: the relationship to classification

Levator function is the key concept in ptosis classification and treatment. We have already stated that levator function is defined as the movement, or excursion, of the eyelid from extreme downgaze to extreme upgaze. It is measured in millimeters with 15 mm being the average normal adult measurement (Figure 8-6). The levator function is the most clinically useful indicator of the health of the levator muscle. Normal movement suggests that the levator muscle has normal strength (Box 8-3). As we have said, the levator function forms the basis of both classification and treatment of ptosis. Does the patient have “normal” levator function? Is the levator function reduced? Is it poor or absent?

Box 8-3 Levator Function

Levator function is the basis of both classification and treatment of ptosis. The extremes are:

• Simple congenital ptosis is associated with reduced levator function

• Involutional ptosis is associated with normal or near normal levator function

• Unusual types of ptosis are usually associated with reduced levator function, but levator function also can be normal

Simple congenital ptosis

Let’s start with some comments on nomenclature. Some classification systems include congenital and acquired ptosis as the major categories. This is appropriate in some ways. Obviously congenital ptosis means that the patient was born with a drooping lid, and acquired ptosis means that the ptosis developed after birth. Unfortunately, so many varied types of ptosis fit into these two categories that you are not given any direction for a treatment plan using this classification. To avoid confusion with the inclusive term congenital ptosis, I like to use the term simple congenital ptosis to describe a specific form of ptosis present at birth. For the most common form of acquired ptosis that occurs late in life, I like to use the term involutional ptosis (Box 8-4).

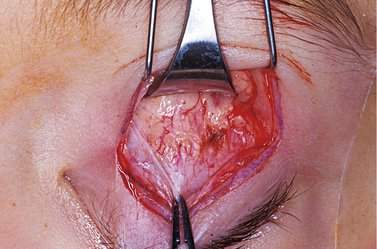

In simple congenital ptosis, the eyelid is ptotic because of a dystrophy of the levator muscle itself. I use the term simple to specify that the only problem is the dystrophic levator muscle. When you perform ptosis surgery on a patient with simple congenital ptosis, you will see that the dystrophic muscle is infiltrated with fatty tissue. The muscle is no longer a healthy red color, but yellowish to a variable degree (Figure 8-7). This weak muscle cannot move well so the levator function is reduced. Usually the degree of ptosis is related to the levator function, that is the lower the levator function, the more ptosis present. In patients with severe ptosis, the levator function may be totally absent. In patients with mild ptosis, the levator function may be minimally reduced.

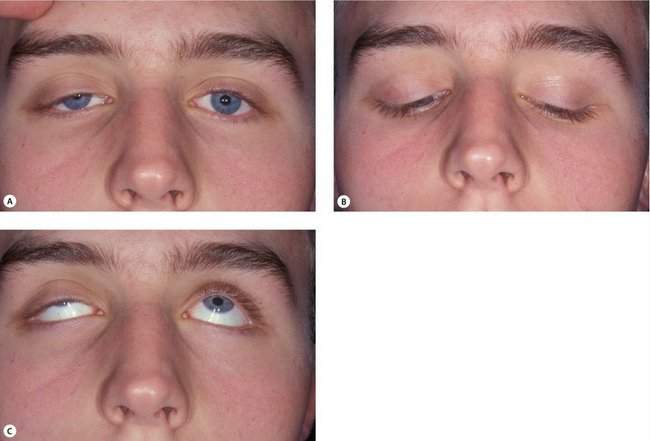

Although we usually think of the upper lid not moving up well, it is probably more accurate to think of the weak and fibrotic muscle not moving well in either upgaze or downgaze. A characteristic of congenital ptosis demonstrating this is known as lid lag on downgaze (Figure 8-8).

Simple congenital ptosis ranges from mild to severe. In essentially all patients with congenital ptosis, the problem is bilateral. Sometimes, the amount of ptosis is quite asymmetric, and parents will only recognize that one side droops (see Figure 8-8). It is worth pointing out the bilaterality because it will probably affect some of the subtleties of the treatment.

Typically, simple congenital ptosis is associated with:

We have stressed that levator function is the key to both classification and treatment of ptosis. For simple ptosis with levator function greater than 4 mm, a levator aponeurosis advancement (tightening the levator) is the correct treatment. Greater amounts of advancement are necessary for diminishing amounts of function. If the levator function is less than 3 mm, a frontalis sling is appropriate. For levator function between 3 and 4 mm, a generous advancement is usual, with the resection extending high above Whitnall’s ligament into the muscle itself (Box 8-5).

Involutional ptosis

Involutional ptosis ranges from mild to severe. It may be bilateral or unilateral. Usually there is an element of bilaterality to the ptosis if you look for it, although the patient often only complains about the more ptotic side.

Typically, involutional ptosis is associated with:

Compare the photos of the patients with simple congenital and involutional ptosis to get these points clear in your mind (Figure 8-9). Although not all patients show these features on examination, the concept is valuable. However, as we will discuss later, the etiology of involutional ptosis as being entirely “aponeurotic” is likely not accurate.

Checkpoint

• Using our simplified classification system, what are the three types of ptosis?

• What are the characteristics of the two most common types of ptosis in terms of the “eyelid vital signs”? Describe the physical characteristics of the levator muscle and aponeurosis that account for the “eyelid vital signs” associated with each ptosis type

History

Introduction

With the background you have so far, you know that most children will have simple congenital ptosis, and most adults will have an involutional type of ptosis. During the history taking and physical examination, you will look for findings that confirm the diagnosis. At the same time, you will be looking for factors that point away from the common diagnosis.

Taking a history in children with ptosis

• Any ptosis will be slightly worse when the patient is tired. Wide variations in the day are not typical of simple congenital ptosis.

• Extreme variation of the lid position from moment to moment suggests a synkinetic form of ptosis. As the name suggests (syn, same; kinesis, movement), these disorders include abnormal simultaneous movements of the lid and another muscle. Ptosis associated with abnormal lid movements caused by chewing, sucking, or other changes in jaw position is known as Marcus Gunn jaw winking. Ptosis associated with abnormal lid movements caused by changes in eye position is seen in third nerve palsy with aberrant regeneration.

Is there a family history of ptosis?

• Strict inheritance of simple congenital ptosis is rare.

• Occasionally a family will have several family members with ptosis without any other associated abnormality.

• More likely, a family history suggests the presence of blepharophimosis syndrome. The epicanthal folds and telecanthus are usually easy to recognize. The facies are usually a well-recognized “family trait” because of the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Often the parent bringing the child will have the syndrome. Sporadic cases are not uncommon, however.

• Congenital ptosis is not commonly associated with any ocular or systemic abnormalities. The dystrophy of the levator muscle is the only abnormality present. Rarely, a congenital ptosis may occur as part of a syndrome. Usually the presence of a syndrome is obvious, based upon physical or neurologic development, but questions about the child’s medical history are appropriate.

Identifying factors that modify the treatment plan

Is the lid open above the pupil? During what part of the day?

• Surgical repair of simple congenital ptosis is usually done before the child starts school (at age 4). Features in the history suggesting the possibility of amblyopia should alter the timing of treatment.

• Amblyopia caused by congenital ptosis is rare. Severe unilateral ptosis is the most likely type to cause amblyopia. Associated astigmatism may also cause amblyopia.

• You should ask the parents to call you if the child stops trying to see out from under the drooping eyelid.

• A history of previous ptosis surgery makes your operation more difficult. Previous ptosis repair, especially levator aponeurosis advancement (tightening) procedures, puts the patient at risk for corneal exposure after more advancement.

By the end of the history taking, you should have an idea whether the ptosis is the simple congenital type. You should also have some idea of what operation the child will need and factors that might influence the timing of the operation. In the physical examination, you will confirm your impressions (Box 8-6).

Taking a history in adults with ptosis

• Determine the etiology of the ptosis

• Identify any characteristics suggesting an unusual type of ptosis

• Identify factors that modify the planned operation

• In the adult, an additional piece of information to obtain is documentation of the effect of the ptosis on the patient’s vision

• Most adults will have an acquired form of ptosis, usually the common involutional type. The onset is difficult to identify as the progression is usually so gradual over several years that no particular time can be identified as the exact onset.

• An acute onset suggests a diagnosis other than involutional ptosis.

• An exception to this is the onset of involutional ptosis after cataract surgery. This is uncommon today, but occurred often when a superior rectus fixation suture was used in cataract surgery.

• Occasionally an adult will have pre-existing congenital ptosis that has slowly gotten worse over time or may have asymmetric congenital ptosis that can no longer be ignored because the “normal” side has progressively drooped more. A review of old photos is rarely necessary because the physical examination will probably confirm the reduced levator function of congenital ptosis.

• Remember that any cause of ptosis in a child persists into adulthood.

Identifying factors that modify the treatment plan

Does the patient have symptoms of “dry” eye? Symptoms such as burning or eye irritation with air movement across the eye may suggest an undiagnosed dry eye condition. The frequent use of eye drops or ointment may mean that the patient has a known dry eye problem (Box 8-7).

Box 8-7 Adult with Ptosis: History Taking

Involutional adult ptosis

What is the patient’s general health?

• Is the patient taking a long list of medications? This may suggest to you that the ptosis repair should be done in an operating room with more supervision than in an office or an outpatient operating room.

• Is the patient particularly nervous during the examination, suggesting to you that you would like an anesthesiologist present to help with sedation?

Physical examination

Introduction

• Classify the type of ptosis based on levator function

• Identify findings suggesting that an unusual ptosis is present

• Document the degree of ptosis

• Look for factors that might modify the usual ptosis operation

You should measure the eyelid vital signs in every patient with ptosis.

The margin reflex distance

The MRD1 measures the degree of ptosis. It should be measured using a penlight and a millimeter rule. With the patient at your eye level, ask him or her to look straight ahead at a distant target. Shine the penlight at the patient’s eye. The distance from the corneal light reflex to the upper lid margin, measured with the millimeter rule, is the MRD1. With some experience, it is easy to estimate the MRD1, if you assume that the corneal diameter is 10 mm and that the normal upper lid resting position is just below the upper limbus. The normal MRD1 is between 4 and 5 mm. If the lid margin crosses the pupil, the MRD1 is 0 mm. If the lid margin is about halfway down from the limbus to the corneal light reflex, the MRD1 is 2.5 mm (a good number to remember because this is the MRD1 often considered to indicate that a visual impairment exists) (Figure 8-10).