Erythema Multiforme: Introduction

|

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute self-limited, usually mild, and often relapsing mucocutaneous syndrome. The disease is usually related to an acute infection, most often a recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. EM is defined only by its clinical characteristics: target-shaped plaques with or without central blisters, predominant on the face and extremities.

The absence of specific pathology, unique cause, and biologic markers has contributed to a confusing nosology. Recent medical literature still contains an overwhelming number of figurate erythema reported as EM, and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD9) still classifies Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) under the heading of EM.

The definition of EM in this chapter is based on the classification proposed by Bastuji-Garin et al.1 The principle of this classification is to consider SJS and TEN as severity variants of the same process, i.e., epidermal necrolysis (EN), and to separate them from EM (see Chapter 40). The validity of this classification has been challenged by some reports, especially for cases in children and cases related to Mycoplasma pneumoniae. It has been confirmed by several others studies however, especially the prospective international Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions study.2 That study demonstrated that, compared with SJS and TEN, EM cases had different demographic features, clinical presentation, severity, and causes.

The original name proposed by von Hebra was erythema exudativum multiforme. The term erythema multiforme has now been universally accepted (Box 39-1).

|

Epidemiology

EM is considered relatively common, but its true incidence is unknown because largely cases severe enough to require hospitalization have been reported. Such cases are in the range of 1 to 6 per million per year. Even though the minor form of EM is frequent than the major form, many other eruptions (including annular urticaria and serum sickness-like eruption) are erroneously called EM.3

EM occurs in patients of all ages, but mostly in adolescents and young adults. There is a slight male preponderance (male–female sex ratio of approximately 3:2). EM is recurrent in at least 30% of patients.

No established underlying disease increases the risk of EM. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus and collagen vascular disorders do not increase the risk of EM, in contrast to their increasing the risk of epidermal necrolysis. Cases may occur in clusters, which suggests a role for infectious agents. There is no indication that the incidence may vary with ethnicity or geographic location.

Predisposing genes have been reported, with 66% of EM patients having HLA-DQB1*0301 allele, compared with 31% of controls.4 The association is even stronger in patients with herpes-associated EM. Nevertheless, the association is relatively weak, and familial cases remain rare.

Etiology

Most cases of EM are related to infections. Herpes virus is definitely the most common cause, principally in recurrent cases. Proof of causality of herpes is firmly established from clinical experience, epidemiology,2 detection of HSV DNA in the lesions of EM,5,6 and prevention of EM by suppression of HSV recurrences.7 Clinically, a link with herpes can be established in about one-half of cases. In addition 10% to 40% of cases without clinical suspicion of herpes have also been shown to be herpes related, because HSV DNA was detected in the EM lesions by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.6 EM eruptions begin on average 7 days after a recurrence of herpes. The delay can be substantially shorter. Not all symptomatic herpes recurrences are followed by EM, and asymptomatic ones can induce EM. Therefore, this causality link can be overlooked by both patients and physicians. HSV-1 is usually the cause, but HSV-2 can also induce EM. The proportion probably reflects the prevalence of infection by HSV subtypes in the population.

M. pneumoniae is the second major cause of EM and may even be the first one in pediatric cases.8–10 In cases related to M. pneumoniae, the clinical presentation is often less typical and more severe than in cases associated with HSV. The relationship to M. pneumoniae is often difficult to establish. Clinical and radiologic signs of atypical pneumonia can be mild, and M. pneumoniae is usually not directly detected. PCR testing of throat swabs is the most sensitive technique. Serologic results are considered diagnostic in the presence of immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies or a more than twofold increase in IgG antibodies to M. pneumoniae in samples obtained after 2 or 3 weeks. M. pneumoniae-related EM can recur.11

Many other infections have been reported to be causes of EM in individual cases or small series, but the evidence for causality of these other agents is only circumstantial. Published reports have implicated infection with orf virus, varicella zoster virus, parvovirus B19, and hepatitis B and C viruses, as well as infectious mononucleosis and a variety of other bacterial or viral infections. Immunization has been also implicated as a cause in children.

Drugs are a rare cause of EM with mucous membrane lesions. Most literature reports of “drug-associated EM” actually deal with imitators, for example, annular urticaria12 or maculopapular eruption with some lesions resembling targets. “EM-like” dermatitis may result from contact sensitization. These eruptions should be viewed as imitators of EM, despite some clinical and histopathologic similarities.

Idiopathic cases are those in which neither HSV infection nor any other cause can be identified. Such cases are fairly common under routine circumstances. However, HSV has been found in situ by PCR in up to 40% of “idiopathic” recurrent cases.9 Some such cases respond to prophylactic antiviral treatment and are thus likely to have been triggered by asymptomatic HSV infection; others are resistant.

Pathogenesis

The underlying mechanisms have been extensively investigated for herpes-associated EM.13 It is unknown whether similar mechanisms apply to EM due to other causes.

Complete infective HSV has never been isolated from lesions of herpes-associated EM. The presence of HSV DNA in EM lesions has been reported in numerous studies using the PCR assay. These studies have demonstrated that keratinocytes do not contain complete viral DNA, but only fragments that always include the viral polymerase (Pol) gene. HSV Pol DNA is located in basal keratinocytes and in lower spinous cell layers, and viral Pol protein is synthesized. HSV-specific T cells, including cytotoxic cells, are recruited, and the virus-specific response is followed by a nonspecific inflammatory amplification by autoreactive T cells. The cytokines produced in these cells induce the delayed hypersensitivity-like appearance in histopathologic evaluation of biopsy sections of EM lesions.

HSV is present in the blood for a few days during an overt recurrence of herpes. If keratinocytes are infected from circulation virus, one would expect disseminated herpes, rather than EM. In fact, HSV DNA is transported to the epidermis by immune cells that engulf the virus and fragment the DNA. These cells are monocytes, macrophages, and especially CD34+ Langerhans cell precursors harboring the skin-homing receptor cutaneous lymphocyte-associated (CLA) marker. Upregulation of adhesion molecules greatly increases binding of HSV-containing mononuclear cells to endothelial cells and contribute to the dermal inflammatory response. When reaching the epidermis the cells transmit the viral Pol gene to keratinocytes. Viral genes may persist for a few months, but the synthesis and expression of the Pol protein will last for only a few days. This may explain the transient character of clinical lesions that are likely induced by a specific immune response to Pol protein and amplified by autoreactive cells. To the best of current knowledge, the mechanisms and regulation of this immune response are different from drug reactivity leading to SJS or TEN.14,15

Clinical Findings

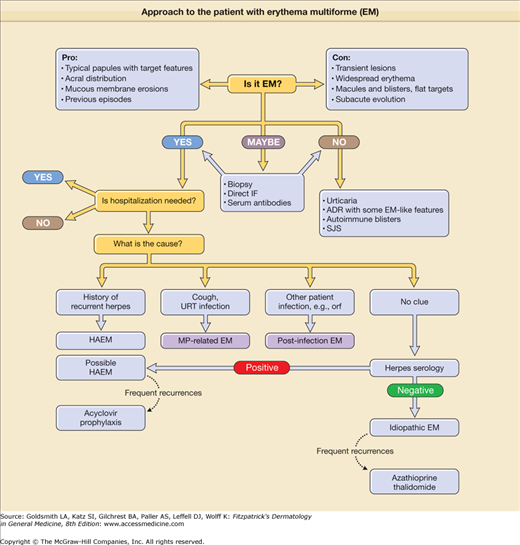

The first step is to suspect EM, based on clinical features. A skin biopsy and laboratory investigations are useful mainly if the diagnosis is not definite clinically. The second step is to determine whether hospitalization is needed when EM major (EMM) occurs with oral lesions severe enough to impair feeding, when a diagnosis of SJS is suspected, or when severe constitutional symptoms are present. The third step is to establish the cause of EM by identifying a history of recurrent herpes, performing chest radiography, or documenting M. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 39-1).

Prodromal symptoms are absent in most cases. If present, they are usually mild, suggesting an upper respiratory infection (e.g., cough, rhinitis, low-grade fever). In EMM, fever higher than 38.5°C (101.3°F) is present in one-third of cases.2 A history of prior attack(s) is found in at least one-third of patients and thus helps with the diagnosis. The events of the preceding 3 weeks should be reviewed for clinical evidence of any precipitating agent, with a special focus on recurrent herpes.

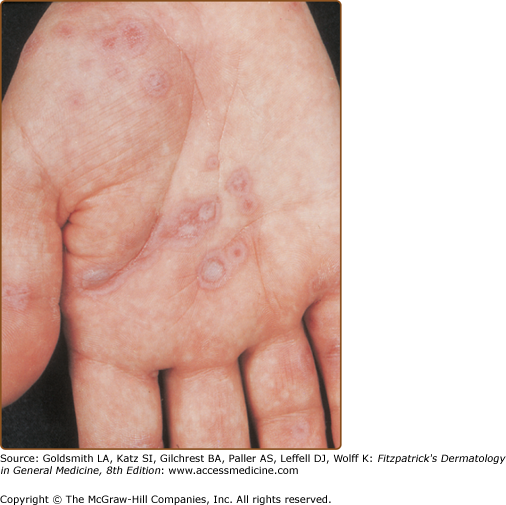

The skin eruption arises abruptly. In most patients, all lesions appear within 3 days, but in some, several crops follow each other during a single episode of EM. Often there are a limited number of lesions, but up to hundreds may form. Most occur in a symmetric, acral distribution on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (hands and feet, elbows, and knees), face, and neck, and less frequently on the thighs, buttocks, and trunk. Lesions often first appear acrally and then spread in a centripetal manner. Mechanical factors (Koebner phenomenon) and actinic factors (predilection of sun-exposed sites) appear to influence the distribution of lesions. Although patients occasionally report burning and itching, the eruption is usually asymptomatic.

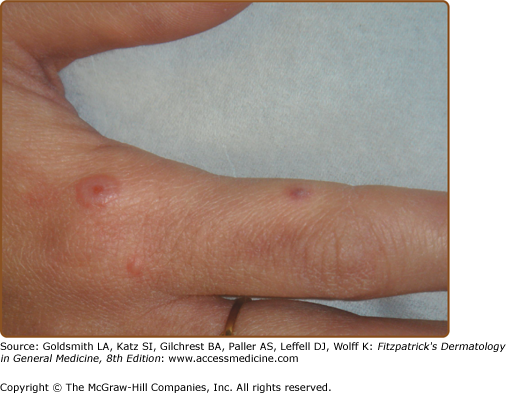

The diversity in clinical pattern implied by the name multiforme is mainly due to the findings in each single lesion; most lesions are usually rather similar in a given patient at a given time. The typical lesion is a highly regular, circular, wheal-like erythematous papule or plaque that persists for 1 week or longer (Fig. 39-2). It measures from a few millimeters to approximately 3 cm and may expand slightly over 24 to 48 hours. Although the periphery remains erythematous and edematous, the center becomes violaceous and dark; inflammatory activity may regress or relapse in the center, which gives rise to concentric rings of color (see Fig. 39-2). Often, the center turns purpuric and/or necrotic or transforms into a tense vesicle or bulla. The result is the classic target or iris lesion.

According to the proposed classification, typical target lesions consist of at least three concentric components: (1) a dusky central disk, or blister; (2) more peripherally, an infiltrated pale ring; and (3) an erythematous halo. Not all lesions of EM are typical; some display two rings only (“raised atypical targets”). However, all are papular, in contrast with macules, which are the typical lesions in epidermal necrolysis (SJS–TEN). In some patients with EM, most lesions are livid vesicles overlying a just slightly darker central portion, encircled by an erythematous margin (Figs. 39-3, 39-4, and 39-5, Fig. 39-8). Larger lesions may have a central bulla and a marginal ring of vesicles (herpes iris of Bateman) (Figs. 39-6 and 39-7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree