10

Endoscopic Forehead Rejuvenation

The symmetry and balance of the face, which are essential components of an aesthetically pleasing visage, are gradually altered as a result of various aging factors. The resulting dissonance of various facial features poses a challenge to the facial plastic surgeon. The dissonance from aging is often most dramatically reflected in the upper third of the face: development of forehead rhytids, sagging of the eyebrows, and hooding of the upper eyelids.

The aesthetic importance of the upper third of the face is well established, and efforts at facial rejuvenation typically focus on this region. For nearly a century, aesthetic rejuvenation of the aging face has involved the surgical elevation of the brow. Several different techniques have been widely utilized to reverse the forehead aging process and to restore a youthful appearance. Three classic approaches to forehead rejuvenation include the coronal forehead lift, the high forehead lift, and the midforehead lift. Despite their popularity, these approaches have carried significant disadvantages such as visible scars, hypoesthesia, alopecia, and the unnecessary removal of healthy hair-bearing skin.

The advent of endoscopic facial plastic surgery has allowed present-day aesthetic surgeons to avoid many of these morbidities without compromising the result. First introduced by Keller in 1991, the endoscopic forehead lift is a minimally invasive technique for forehead rejuvenation. Under endoscopic visualization the surgeon may perform myotomies of the muscles contributing to brow ptosis and forehead rhytids, as well as temple lifts. When compared with the classic approaches, several advantages are evident with the endoscopic technique: preservation of the scalp sensory nerves, better control of brow position, accurate resection of brow depressor muscles, decreased postsurgical numbness and edema with a shorter recovery period, and preservation of hair-bearing skin.

Since its introduction many authors have reported their personal experiences and have offered various modifications of the endoscopic technique. There has been great success with the technique, with long-lasting results equivalent to those of the traditional open approaches, yet without the associated morbidity of the traditional procedures. Accordingly, many surgeons are now choosing the endoscopic technique in preference to coronal brow lift procedures.

The Aging Process

The Aging Process

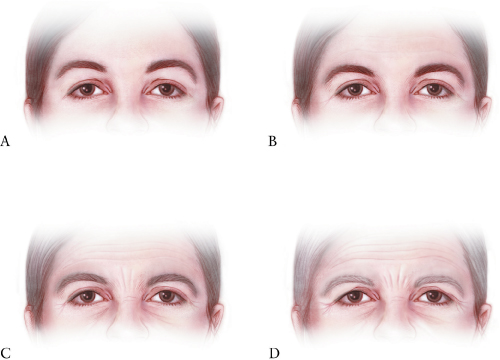

Aging is a gradual process in which the smooth, wrinkle-free skin of youth is altered. This process begins to manifest itself in the forehead region as early as the fourth decade, at which point horizontal lines begin to appear. These lines begin to deepen and vertical lines form in the glabella during the fifth decade. Concurrently, the eyebrows begin to descend and flatten with prolapse of the infrabrow tissue over the thin eyelid skin, leading to medial and lateral hooding of the upper eyelid. These various changes combine to alter the aesthetically appealing Y-shaped sweep between the eyebrow, medial orbit, and lateral nose to a T-shaped impression. The result is a countenance seemingly conveying anger, sadness, or fatigue (Fig. 10-1A-D).

The aging effects on forehead skin are pronounced because of the uniquely intimate relationship between the skin and muscle of the upper third of the face. With minimal subcutaneous tissue present to separate skin from muscle, the repetitive actions of facial muscles are directly transmitted to the overlying skin, predisposing this region to develop deep wrinkles and furrows. Ellis and Masai1 have previously discussed three basic patterns of facial animation that lead to the development of rhytids and brow ptosis: eyebrow raising, frowning, and squinting. Eyebrow raising, which involves the contraction of the frontalis muscles, gradually but permanently establishes horizontal wrinkles on the forehead. The most inferior horizontal rhytid, over the radix of the nose, is due to the action of the procerus muscle. Frowning reflects the action of the corrugator supercilli muscles to bring the medial club heads of the eyebrows together, resulting in deep vertical glabellar rhytids. Lastly, repeated squinting—contraction of the orbicularis oculi—causes “crow’s feet” at the lateral canthus.

Figure 10-1 Aging process in the forehead region. (A) A young wrinkle-free forehead develops (B) horizontal rhytids by the fourth decade. (C) Vertical glabellar furrows begin to develop subsequently. (D) Ultimately, an appearance seemingly conveying anger, sadness, or fatigue results. (Courtesy of Karl Storz Endoscopy-America, Inc., Culver City, California.)

Aesthetic balance requires that the vertical proportion of the middle third of the face be equivalent to that of the lower third. With forehead aging and the resultant brow ptosis, the middle third of the face becomes increasingly compressed and narrowed in comparison to the lower third. Rejuvenation of the upper third of the face serves to restore balance and symmetry to the lower two thirds of the face.

Forehead Anatomy

Forehead Anatomy

A comprehensive understanding of surgical anatomy is a prerequisite for any successful cosmetic surgical procedure. This is particularly true with the use of the endoscope, which necessitates a different perspective on the forehead anatomy. Appreciation of the various features of forehead musculature, fascia, and neurovascular structures will afford the surgeon superior results while avoiding potential complications.

Scalp and Forehead Musculature

The scalp is composed of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, aponeurosis or galea, loose areolar tissue, and periosteum. The galea aponeurotica is a connecting band of tissue between the bellies of the frontalis and occipital muscles. Contraction of these muscles causes the scalp to slide back and forth over the underlying loose areolar plane. Laterally, the galea merges with the temporalis fascia.

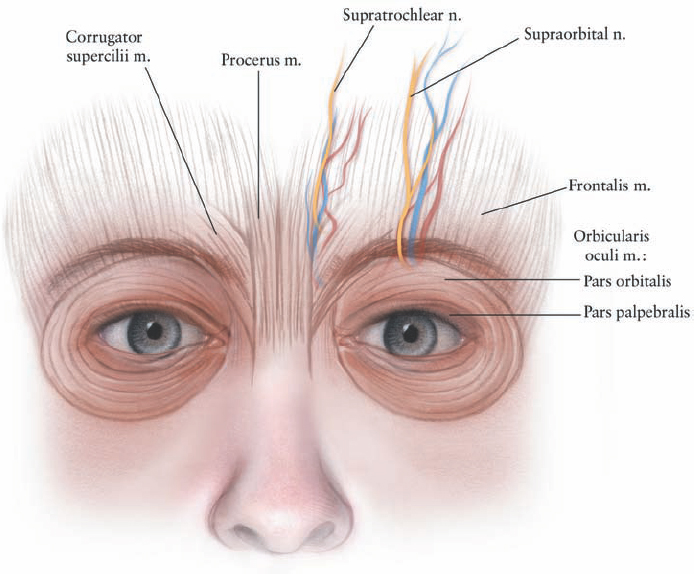

The occipitofrontalis muscle consists of thin and wide muscle bellies joined through the intermediate aponeurosis. At the coronal suture, the galea gives rise to the insertion of the frontal bellies, which frequently appear in a quadrilateral shape. The frontalis is contiguous with the procerus muscle (via medial fibers), corrugator supercilii muscle (via intermediate fibers), and the pars orbitalis of the orbicularis oculi muscle (via lateral fibers) (Fig. 10-2). The perceived action of the occipitofrontalis muscle, functioning as a unit, is to raise the eyebrows with an associated transverse creasing of the forehead. The frontal bellies, acting separately, only raise the eyebrows. The occipitofrontalis muscle is the only elevator of the brow, whereas there are four muscles that are depressors of the brow: the procerus, pars orbitalis of orbicularis oculi, depressor supercilii, and corrugator supercilii.

The procerus is a small pyramidal muscle arising from the fascia overlying the cephalic portion of the upper lateral nasal cartilages and the inferior aspect of the nasal bones. The muscle fibers, which interdigitate with the medial border of the frontalis muscle, insert into the skin between the eyebrows. Contraction of the procerus leads to the pulling down of the glabella and results in the formation of the lowermost horizontal rhytid over the radix of the nose.

The pars orbitalis is the only one of the three components of the orbicularis oculi that has an impact on eyebrow motion. The attachment of the superomedial fibers of the pars orbitalis to the brow allows it to function as one of the main depressors of the brow. The depressor supercilii muscle is located on the medial arc of the orbicularis oculi and is considered by some to be a part of the larger muscle. This muscle acts in concert with the corrugators to depress the medial brow.

The corrugator supercilii is a complex muscle consisting of both transverse and oblique heads. The muscle originates from the medial portion of the supraorbital rim and inserts into the dermis of the medial eyebrow, deep to the orbicularis and frontalis muscles. At their medial point of insertion, the corrugator muscle fibers blend with those of the pars orbitalis and the frontalis. The contraction of the corrugator pulls the eyebrow medially and leads to the development of deep vertical furrows.

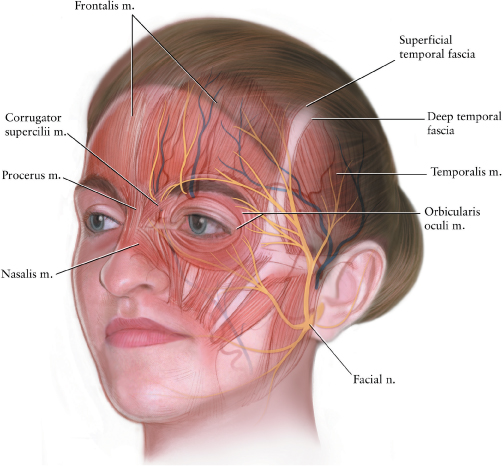

Fascia

During an endoscopic forehead lift, the dissection crosses several fascial planes, and a detailed understanding of these planes allows the surgeon to safely approach the brow. The superficial temporal fascia (i.e., temporoparietal fascia) is the first fascial plane encountered just underneath the skin and subcutaneous fat of the temporal area. Within this plane the temporal artery and vein may be found superiorly. The superficial temporal fascia merges inferiorly with the extensive superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) of the lower face and is in continuity with the galea superiorly, the frontalis anteriorly, and the occipitalis posteriorly2 This fascial layer lies superficial to the zygomatic arch and encompasses the temporal branch of the facial nerve (Fig. 10-3).3 Beneath the superficial temporal fascia lies the subaponeurotic plane, which is a loose areolar plane separating the superficial temporal fascia from the layer of deep temporal fascia.4 Dissection in the temporal region should proceed within this plane, just on the deep temporal fascia. This allows the surgeon to avoid the temporal branch adherent to the undersurface of the superficial temporal fascia. Violation of the deep temporalis fascia exposes the underlying deep temporal fat pad, which may then atrophy and result in temporal wasting.

Figure 10-2 Musculature and neurovascular structures of the forehead. The frontalis is the sole elevator of the brow, the remaining forehead muscles function as brow depressors. The supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves provide sensation to the forehead. (Courtesy of Karl Storz Endoscopy-America, Inc., Culver City, California.)

Figure 10-3 Relevant surgical anatomy of the forehead and midforehead. The surgeon should appreciate the various fascial planes and their relationship to relevant neurovascular structures. (Courtesy of Karl Storz Endoscopy-America, Inc., Culver City, California.)

Neurovascular Structures

Sensation of the forehead is provided by the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves arising from the first branch of the trigeminal nerve. The supraorbital nerve exits the skull via the supraorbital foramen in the midpupillary line—lateral to the supratrochlear nerve—in association with the supraorbital artery. The supraorbital nerve is the predominant sensory nerve of the forehead. The fibers of the supratrochlear nerve are often located within the corrugator muscle, 8 to 12 mm medial to the supraorbital nerve (Fig. 10-2).

The facial nerve supplies all the muscles of facial expression (Fig. 10-3). Specifically, the temporal branch of the facial nerve innervates the frontalis and corrugator muscles, whereas the zygomatic branch innervates the procerus, depressor supercilii, and orbicularis oculi.5 The temporal branch of the facial nerve may be found during an endoscopic approach by locating a series of bridging vessels between the superficial and deep temporal fascial layers. The point at which the bridging vessels insert into the superficial temporalis fascia identifies the site of the temporal branch as it courses superficially through the fascia. At the level of the frontozygomatic suture, 1.5 cm lateral to the lateral canthus, the sentinel vein can be found. This vein is the medial branch of the zygomaticotemporal vein (a tributary of the internal maxillary vein) and drains the temporal region. The sentinel vein serves as a reliable marker for the facial nerve, which is found just lateral to it.6

Forehead and Brow Facial Analysis

Forehead and Brow Facial Analysis

The concept of attractiveness and beauty in facial aesthetics is not defined by any single particular attribute, but rather by the combination of facial features and aesthetic balance. It is the facial plastic surgeon’s objective to identify and improve upon any distinct qualities or proportions of the face that are perceived to be undesirable by the patient and society. With this in mind, authors have proposed numerous methodologies for facial analysis. The concept of the ideal forehead and brow has been extensively explored, and several common principles have emerged.

Facial height in Caucasians can be evaluated by dividing the face into equal thirds. The upper third of the face contains the forehead and extends from the trichion to the glabella and superior aspects of the eyebrows laterally. In men there is a greater prominence of the supraorbital ridge with more supraorbital bossing as compared with women, who have a more gradual curvature of the forehead.

The brow shape and position vary on the basis of sex. The classically described brow position in a female has the following characteristics7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree