Ear Reconstruction

Charles H. Thorne

PARTIAL ACQUIRED DEFECTS

Most acquired, partial auricular defects have a good surgical solution. The more superior on the ear the defect is located, the more choices there are for reconstruction. Reconstruction of the lobule is the most difficult and is aesthetically the most important.

Although some defects can be closed by soft tissue alone, cartilage is usually required for support. For smaller defects, a conchal cartilage graft may suffice. However, for larger defects the rules of Firmin (Firmin, Personal communication, 2013) are extremely helpful: Defects that consist of 25% or more of the helical rim or involve more than two planes (i.e., involve antihelix as well as helix and scapha) will require rib cartilage for support. Conchal cartilage will not provide sufficient support in these cases.

Specific Regional Defects

External Auditory Canal.

Stenosis is best treated by a full-thickness graft applied over an acrylic mold, provided a reasonable recipient vascular bed can be prepared. Occasionally, multiple Z-plasties are used to relieve webbing of the orifice, or a local flap is employed to line the canal and break up the contracture. An acrylic stent is recommended for several months to counteract the inexorable tendency toward contracture.

Helical Rim.

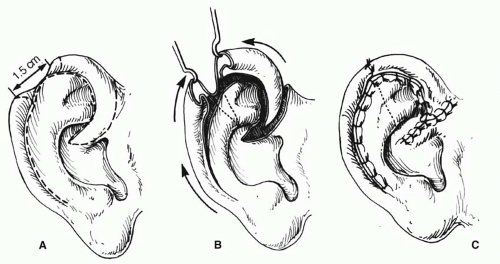

Acquired losses of the helical rim vary from small defects to major portions of the helix. The former defects, which usually result from tumor excisions or minor traumatic injuries, are best closed by advancing the helix in both directions, as described by Antia and Buch1 (Figure 27.1). The success of this excellent technique depends first on freeing the helix from the scapha via an incision in the helical sulcus that extends through the cartilage but not through the posterior skin. The posterior auricular skin is undermined, until the entire helix is hanging as a chondrocutaneous flap on the posterior skin. Extra length can be gained by a V-Y advancement of the helical crus, as described in the correction of the constricted ear. Defects up to 1.5 cm can be closed without tension. Defects larger than 2 cm are too large for this technique. In order to facilitate closure, it is necessary to “cheat” by removing some of the scaphal cartilage, taking tension off the reapproximated helical rim. Reducing the scapha reduces the size of the ear and the patient should be alerted to this fact in advance. Although originally described for upper-third auricular defects, this technique is also effective for middle-third defects, as well as for defects at the junction of the middle and lower thirds.

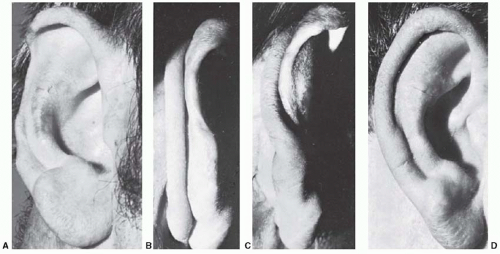

If the helical rim alone is missing, as may occur in burn injuries, a thin tube of retroauricular skin can be applied to the residual scapha with acceptable results (Figure 27.2). This is one example where cartilage may not be necessary. The disadvantage of this technique is that it requires three stages to “waltz” the tube into place: (a) formation of the tube in the sulcus, (b) transfer and insetting of one end of the tube, and (c) transfer and insetting of the other end of the tube.

Upper-Third Defects.

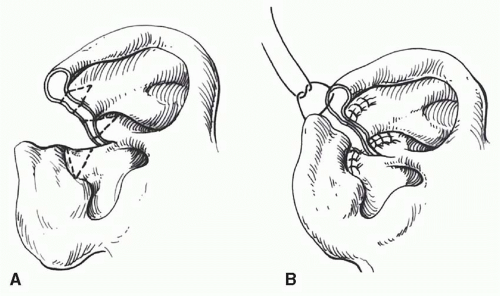

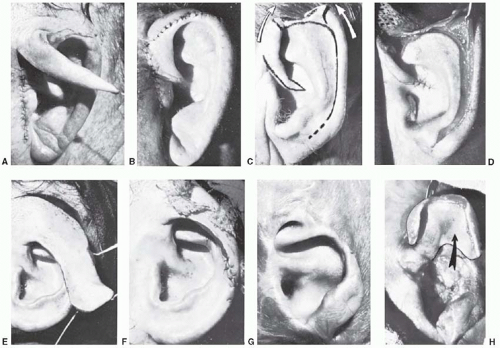

Techniques available for upper-third defects in increasing order of size and complexity are as follows (Figure 27.3):

Local skin flaps (Figure 27.3 A and B)

Helical advancement (Figure 27.3 C and D).

Contralateral conchal cartilage graft covered with a retroauricular flap (Figure 27.3 E and F).

Chondrocutaneous composite flap (Figure 27.3 G and H).

Rib cartilage graft covered with retroauricular skin or temporoparietal flap/skin graft (see Figure 27.5).

Middle-Third Defects.

Techniques available for middle-third defects are as follows:

Primary closure with excision of accessory triangles (Figure 27.4).

Helical advancement.

Conchal cartilage graft and retroauricular flap.

Rib cartilage graft and retroauricular flap and/or temporoparietal flap (Figure 27.5).

FIGURE 27.3. Four techniques for repairing upper-third auricular defects. A and B. Preauricular flap. The flap is transposed to repair a minor rim defect. C and D. Antia-Buch helical advancement. E and F. The combination of a retroauricular flap and conchal cartilage graft. G and H. Chondrocutaneous conchal flap to reconstruct the helical rim. Of the upper-third techniques, the only one not shown is a rib cartilage graft, which is shown in Figure 30.11. (Courtesy of Burt Brent, MD.) |

Cartilage grafts can be inserted via the Converse tunnel procedure in which the skin is not detached at the junction of the residual ear and the retroauricular skin. The problem is that precise placement of the graft with exact coaptation

to remaining cartilage is difficult using this approach, and a detached retroauricular flap (Figure 27.5) is preferable. Middle-third auricular tumors are excised and closed by either a wedge resection with accessory triangles (Figure 27.4) or a helical advancement, as previously described.

to remaining cartilage is difficult using this approach, and a detached retroauricular flap (Figure 27.5) is preferable. Middle-third auricular tumors are excised and closed by either a wedge resection with accessory triangles (Figure 27.4) or a helical advancement, as previously described.

Lower-Third Auricular Defects.

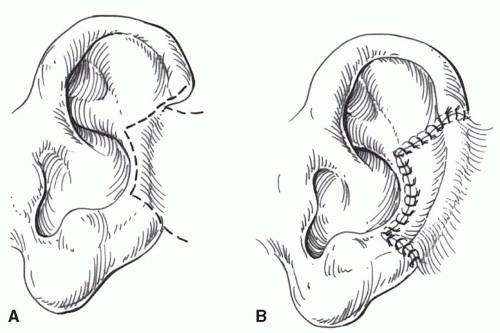

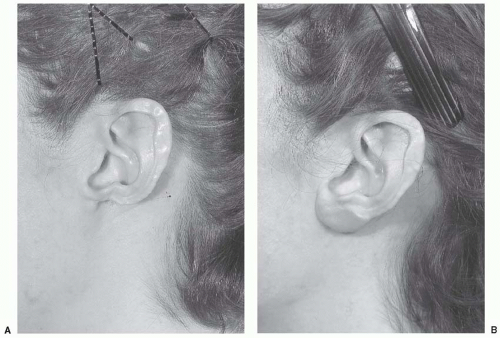

Various techniques have been described to reconstruct earlobe defects using soft-tissue flaps. These techniques are not as effective as those that employ cartilaginous support. Like the alar rim, the normal earlobe does not contain cartilage. A reconstructed earlobe, however, will only maintain its contour if cartilage is included, analogous to nonanatomic alar rim grafts. The author prefers to use thin, flat cartilage obtained from the nasal septum.2 The cartilage is placed beneath the cheek/retroauricular skin in the first stage. A hole can be made in the cartilage at this initial stage for later ear piercing. In the second stage, an incision is made around the cartilage graft and the flap is advanced beneath the earlobe as in a facelift (Figure 27.6).

MICROTIA

Microtia literally means small ear. The simplicity of the term belies the vast complexity of this entity, in terms of both the variable clinical presentation and the difficulty of surgical reconstruction.

History

Gillies is credited with the first use of rib cartilage for construction of an auricular framework in 1920. The importance of his contribution was temporarily obfuscated by several reports using allogeneic cartilage. The allogeneic cartilage, whether from a living donor such as the patient’s parent or preserved cadaver cartilage, always underwent gradual resorption.

The modern era of auricular reconstruction began with Tanzer3 who reintroduced the technique of autogenous costal cartilage grafts as a method of auricular reconstruction. Tanzer’s results inspired Brent who modified, improved, and standardized a four-stage technique of auricular reconstruction.4 Nagata developed a more complex technique that condensed microtia repair into two stages.5 The Nagata technique requires more cartilage and the construction of a higher profile, more detailed framework than the Brent technique. Firmin analyzed those characteristics of a “Brent ear” that fall short of a normal ear and reported a large series using her modification of the Nagata technique.6

While the technique of autogenous auricular reconstruction was evolving, silastic was also used, instead of rib cartilage, as the auricular framework. This material, as well as other artificial materials, led to a high incidence of extrusion. More recently, the use of porous polyethylene frameworks has been explored and has become the standard treatment offered by some surgeons. The largest series was reported by Reinisch.7 Early attempts were associated with a 42% incidence of framework extrusion leading to modifications of the original technique and coverage of the framework using a temporoparietal fascial flap. This drastically reduced the complication rate and is the technique of choice in his opinion.

Finally, an auricular prosthesis is another option. The introduction of titanium osseointegrated fixtures by Branemark has made prosthetic reconstruction of the auricle a more stable and user-friendly alternative.8 The role of prosthetic reconstruction in microtia will also be discussed later.

Anatomy and Surgical Challenge

The ear is composed of a delicate and complex-shaped cartilage framework covered on its visible surface with thin, tightly adherent, hairless skin. A reconstructed auricular framework must be more rigid than the cartilage framework of a normal ear. When the auricular framework is placed beneath the skin in the temporal region, a combination of the tight skin envelope and the progressive scar contracture will gradually obliterate the fine details if the framework is built to mimic the delicate framework of the normal ear. As such, any reconstructed ear that maintains its projection and definition in the long term will be more bulky and will lack the flexibility of the normal ear.

Consequently, even the best result using current techniques for auricular reconstruction is imperfect. The deficiencies of current techniques make it even more important that the reconstructed auricle be the correct size, be located in the proper position such that one earlobe is not higher than the other, and be properly angulated relative to the other facial structures.

Embryology

The middle and external ears are derived from the first (mandibular) and second (hyoid) branchial arches. Most patients with microtia have atresia (absence) of the external auditory canal and tympanic membrane with variable deformities of the middle ear ossicles. Rarely, a patient will present with microtia and a patent, stenotic canal. Least common but most difficult to repair are patients with an auricular vestige and canal that are markedly abnormal in position. Because

the meatus can only be moved a limited distance, the surgeon must consider complete excision of the canal.

the meatus can only be moved a limited distance, the surgeon must consider complete excision of the canal.

FIGURE 27.6. Earlobe reconstruction using nasal septal cartilage. A. Original defect secondary to discoid lupus erythematosus. B. Final result after two-stage reconstruction using thin cartilage from the nasal septum. (Copyright of Charles H. Thorne, MD).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|