Drainage of Breast Cysts and Abscesses

Amy C. Degnim

Breast Cysts

Breast cysts are common, both as identifiable symptomatic lesions and as asymptomatic findings during screening or diagnostic breast imaging. Prior to the widespread use and availability of ultrasound, most cysts were diagnosed and treated simultaneously with fine needle aspiration. In the current era, management of breast cysts is determined by their imaging appearance and symptoms. A symptomatic breast cyst classically presents as a smooth, well-circumscribed, mobile, soft-to-firm lump; tenderness is variable and is based on the degree of fluid tension within the cyst. Cysts that present as palpable breast lesions should be evaluated with ultrasound prior to intervention, if at all possible. This is a feasible goal, given common availability of good-quality portable ultrasound units and increasing numbers of surgeons trained in basic ultrasound. Diagnostic mammography is also standard in the imaging evaluation of new palpable lesions in women 35 years and older.

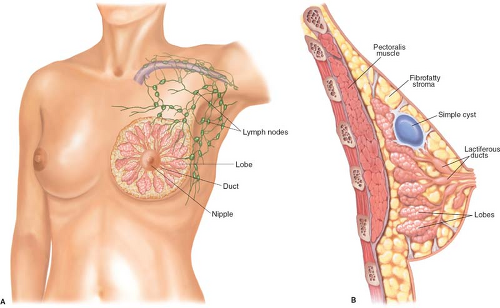

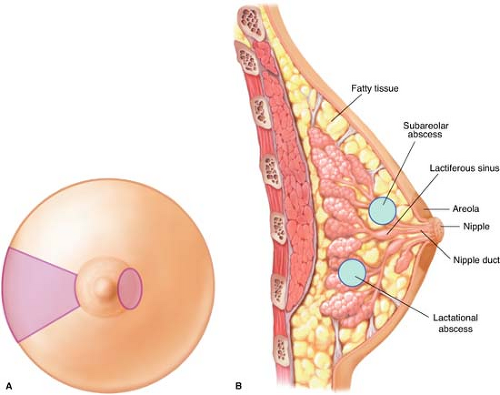

The breast is a glandular organ that serves the purpose of postpartum lactation. The normal anatomy comprises 15 to 20 lobar structures that are supported in fibrofatty stromal tissue. The lobar glandular elements are connected via microscopic ducts that converge in the central breast under the areola and exit through the nipple (Fig. 2.1A). In the subareolar location, the ducts dilate as lactiferous sinuses that act as small reservoirs of milk in the lactating state. Breast cysts can occur anywhere in the breast but most commonly are found within the parenchyma of the breast outside the nipple/areolar location (Fig. 2.1B).

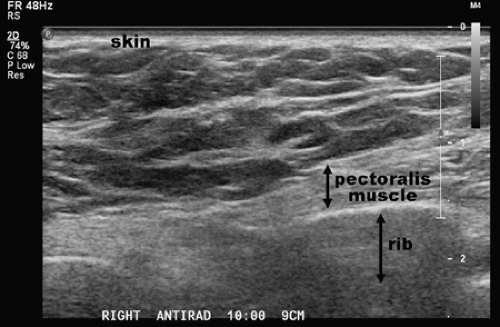

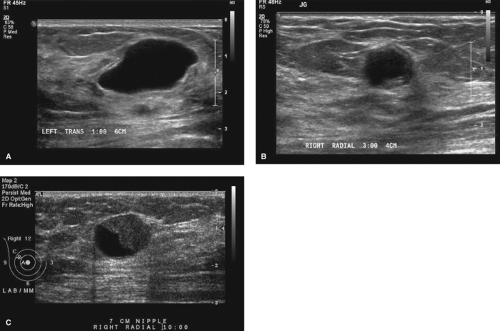

Ultrasound is the primary diagnostic modality for diagnosis of breast cysts, with high sensitivity at discriminating fluid versus solid lesions. By ultrasound, normal breast tissue demonstrates some heterogeneity in echogenicity of the parenchyma but does not show discrete abnormalities (Fig. 2.2). When evaluating cysts sonographically, the location, size, borders, and internal echogenicity should be noted and recorded in detail to facilitate future comparison. The ultrasonographic criteria for diagnosis of a simple cyst are well established, such that asymptomatic simple cysts do not require aspiration. These strict

sonographic features are anechoic (containing no echoes), sharply circumscribed margins, posterior acoustic enhancement, and refractive (edge) shadows (Fig. 2.3A). Simple cysts that meet these criteria do not require aspiration unless painful or worrisome to the patient. Some overlap exists with features and terminology of complex cysts and complex masses, but any solid component of a lesion in the breast should undergo tissue biopsy. Complex cysts are those that truly are cysts but do not meet the strict sonographic criteria for simple cysts (Fig. 2.3B). When ultrasound shows internal echoes, ill-defined margins, or wall thickening, the lesion should be described as a complex mass despite the presence of some cystic features (Fig. 2.3C). Complex cysts should undergo aspiration, and complex masses should be treated as solid masses and undergo core needle biopsy. In summary, cysts with indications for aspiration are simple cysts that are symptomatic, and complex cysts that do not meet strict sonographic criteria for simple cysts.

sonographic features are anechoic (containing no echoes), sharply circumscribed margins, posterior acoustic enhancement, and refractive (edge) shadows (Fig. 2.3A). Simple cysts that meet these criteria do not require aspiration unless painful or worrisome to the patient. Some overlap exists with features and terminology of complex cysts and complex masses, but any solid component of a lesion in the breast should undergo tissue biopsy. Complex cysts are those that truly are cysts but do not meet the strict sonographic criteria for simple cysts (Fig. 2.3B). When ultrasound shows internal echoes, ill-defined margins, or wall thickening, the lesion should be described as a complex mass despite the presence of some cystic features (Fig. 2.3C). Complex cysts should undergo aspiration, and complex masses should be treated as solid masses and undergo core needle biopsy. In summary, cysts with indications for aspiration are simple cysts that are symptomatic, and complex cysts that do not meet strict sonographic criteria for simple cysts.

Percutaneous aspiration of a cyst can be performed either in freehand fashion or with ultrasound guidance. Ultrasound guidance is strongly preferred for several reasons: (1) it will help to achieve maximal drainage and (2) it will evaluate for any residual mass after aspiration that may be present but not palpable once the bulk of fluid is removed. It is not necessary to discontinue aspirin or anticoagulants such as warfarin for a fine needle aspiration. As with all procedures, informed consent should be obtained via discussion with the patient. All materials should be assembled and ready, including skin prep solution, sterile drape and gloves, 21-gauge needle, 5- or 10-mL syringe, and a plastic strip bandage. After skin prep and drape, the needle should be attached to the syringe and the plunger worked to ensure it is moving freely. If ultrasound is not available, a freehand technique may be used.

Freehand Technique of Cyst Aspiration

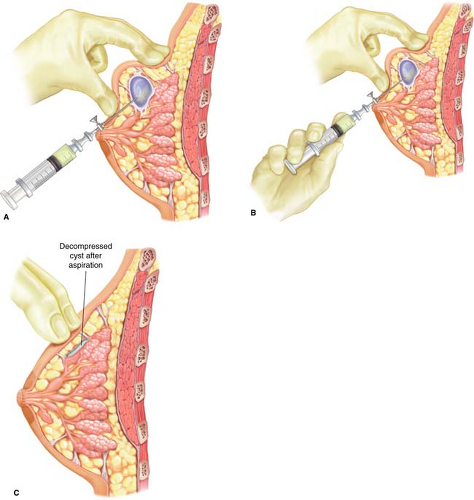

For this approach, the lesion is stabilized between the thumb and the fingers of the nondominant hand (Fig. 2.4A). The syringe is grasped with the dominant hand across the palm with the needle end of the syringe extending between the thumb and the forefinger, such that the fourth finger and the fifth finger can withdraw the plunger, enabling the operator to direct the needle and apply suction simultaneously (Fig. 2.4B). Local anesthetic can be applied in a skin wheal but is not necessary. Needle entry site is

planned such that the needle tract will be parallel to the chest wall in order to avoid pneumothorax. After skin prep, the needle is placed under the skin and negative pressure is applied to the syringe. The needle is advanced directly into the lesion, maintaining negative pressure in the syringe. The cyst is aspirated until there is no residual palpable mass (Fig. 2.4C). Aspirated fluid that is nonbloody may be simply discarded. If the aspirate is bloody or gelatinous, postaspiration imaging and tissue biopsy are indicated. Cytologic evaluation of bloody aspirate fluid is obtained in some practices, but this practice is not routinely recommended, as false-negative cytology is common among inexperienced samplers and pathologists not specially trained in cytology. Should a residual mass be palpable after cyst aspiration, repeat imaging is required to evaluate whether there is persistent cystic fluid that was not adequately drained or whether there is a residual solid component to the palpable mass that requires tissue biopsy.

planned such that the needle tract will be parallel to the chest wall in order to avoid pneumothorax. After skin prep, the needle is placed under the skin and negative pressure is applied to the syringe. The needle is advanced directly into the lesion, maintaining negative pressure in the syringe. The cyst is aspirated until there is no residual palpable mass (Fig. 2.4C). Aspirated fluid that is nonbloody may be simply discarded. If the aspirate is bloody or gelatinous, postaspiration imaging and tissue biopsy are indicated. Cytologic evaluation of bloody aspirate fluid is obtained in some practices, but this practice is not routinely recommended, as false-negative cytology is common among inexperienced samplers and pathologists not specially trained in cytology. Should a residual mass be palpable after cyst aspiration, repeat imaging is required to evaluate whether there is persistent cystic fluid that was not adequately drained or whether there is a residual solid component to the palpable mass that requires tissue biopsy.

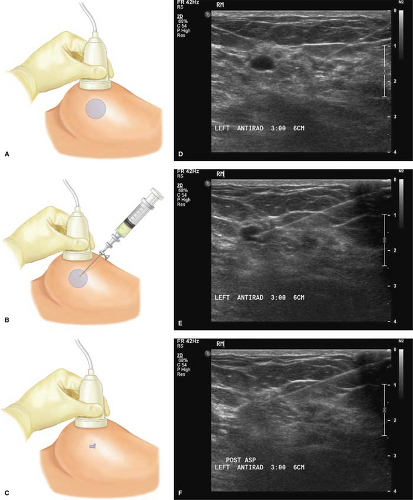

Ultrasound-guided Percutaneous Aspiration of a Breast Cyst

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous aspiration of a breast cyst is performed according to standard techniques for image-guided breast biopsy. As in freehand aspiration, a 21-gauge needle and a 5- or 10-mL syringe are used. The lesion is visualized optimally with ultrasound and stabilized under the transducer with the nondominant hand (Fig. 2.5A,D). After antiseptic skin prep, the needle is advanced at a 45-degree angle in line with the long axis of the ultrasound transducer into the field of view and into the center of the cyst (Fig. 2.5B,E). All fluid is aspirated until the cyst completely disappears (Fig. 2.5C,F). As in freehand aspiration, any lesions with bloody aspirate or residual mass–like features require core needle diagnostic biopsy.

Having all necessary materials available and ready facilitates a smooth procedure. It is also helpful to have an assistant available to converse with the patient and provide reassurance during the procedure; in addition, this reduces interruption of the procedure if an additional syringe or other supply is needed. Always be aware of the depth of the target lesion within the breast and the position of the needle tip in order to avoid pneumothorax as a possible complication. If frank blood is encountered in an aspiration, withdraw the needle and hold direct pressure over the site for at least 5 minutes. The procedure should be aborted and reattempted another day, once any hematoma has resolved.

For palpable/symptomatic simple cysts, a follow-up visit in 4 to 6 weeks is recommended to identify early recurrence of the cyst, although the value of this practice has been recently questioned. If the cyst recurs within this short period of time, then surgical excision is recommended. If the cyst is not palpable and initial diagnostic imaging was negative other than the cyst, then the patient is recommended to return to routine breast cancer screening guidelines. Simple cysts that are detected incidentally do not require any specific follow-up, and routine screening guidelines may be resumed.

There are very few complications of cyst aspiration. Bruising, hematoma, and infection can occur rarely, and the risk of pneumothorax is remote.

Ultrasound is the preferred diagnostic evaluation for suspected cystic lesions, and diagnostic mammography should also be performed for women aged 30 to 35 years and older. Simple cysts that are asymptomatic do not require aspiration, which is indicated for symptomatic simple cysts and complex cystic lesions. Most aspirated cysts do not recur rapidly, with only approximately 10% clinically apparent at 6- to 8-week follow-up visit. Ultrasound guidance is recommended for aspiration and allows immediate determination of the therapeutic benefit of the procedure as well as determination of any residual mass lesion and thus which patient should undergo core needle biopsy, since up to 25% of complex cysts and 50% to 60% of cystic masses harbor cancer.

Figure 2.5 Ultrasound-guided cyst aspiration: (A/D) Center ultrasound transducer over cyst, (B/E) direct needle along long axis of transducer over the cyst, and (C/F) collapsed cyst after aspiration. |

Table 2.1 Features of Lactational and Nonlactational Abscesses | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Breast Abscesses

Breast abscesses are generally categorized as one of two types: lactational abscesses and nonlactational abscesses (alternate terminology is puerperal and nonpuerperal abscesses). These two different types of breast abscesses have different profiles in terms of etiology, location, microbiology, and relapse patterns (Table 2.1; Fig. 2.6A,B). Nonlactational breast abscesses can occur at virtually any age, whereas lactational abscesses are most common in the third decade of life as would be expected around the childbearing years. Because of differences in their nature and treatment, these two entities will be discussed separately.

Lactational Abscesses

By definition, lactational abscesses are associated with lactation in the puerperium. Specifically, this includes abscesses occurring during pregnancy, lactation, or within the first 3 months after cessation of lactation. Inspissated secretions and stasis of the breast milk with its intrinsic sugar content provide the ideal bacterial culture medium, and infection can progress rapidly. The responsible organism is almost always Staphylococcus aureus, attributable to the skin flora of the breast and also present in the oral flora of the suckling infant. Usually, lactational abscesses are preceded by lactational mastitis, characterized by fever, malaise, and exquisite tenderness (with or without overlying erythema) in a segmental area of the breast gland. Occasionally, systemic sepsis can be evident. Prompt treatment with antibiotics is paramount to prevent progression to abscess–-oral antibiotics if the patient is stable and intravenous if septic. Dicloxacillin for 14 days is the recommended regimen. Rest, increased fluid intake, and more frequent suckling of the infant are additional important components of treatment to help clear the ductal obstruction. Diagnostic ultrasound should be obtained if there is any suspicion of abscess at presentation or if rapid clinical improvement does not occur with antibiotic therapy. If mastitis progresses to lactational abscess, then drainage is indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree