Disorders with Malignant Potential

Lawrence Eichenfield M.D.

Clinical Pearls

(LE)

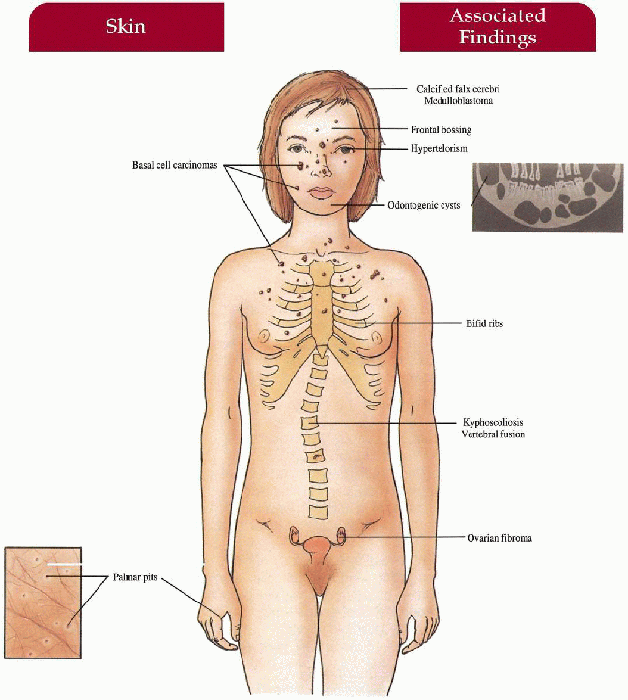

Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Synonym

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome

Gorlin syndrome

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant; PTCH1 (PATCHED1) gene on 9q22-31

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA mutation analysis

Incidence

Approximately 1:60,000; M=F

Age at Presentation

Birth (bossing, skeletal anomalies); childhood (jaw cysts, basal cell carcinoma)

Pathogenesis

Mutations in PTCH1, a tumor suppressor gene encoding the sonic hedgehog transmembrane receptor protein; receptor interacts with signaling proteins important for controlling cell fate, patterning, and growth

Key Features

Skin

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs)—multiple, skin-colored to tan, dome-shaped papules on face, neck, trunk

Palmoplantar pits—2- to 3-mm erythematous pits, rarely develop into BCCs; milium, epidermoid cysts

Musculoskeletal

Jaw cysts (odontogenic keratocysts)—secondary pain, swelling, drainage, increased in molar and premolar areas in maxilla, usually multiple, lining with malignant potential

Frontal bossing, bifid ribs, vertebral fusion, kyphoscoliosis

Central Nervous System

Calcification of falx cerebri, agenesis of corpus callosum, medulloblastoma, mental retardation (less common)

Eyes

Hypertelorism, congenital blindness, cataracts, colobomas, strabismus

Genitourinary

Ovarian fibromas, fibrosarcoma

Differential Diagnosis

Bazex syndrome

Unilateral linear nevoid basal cell carcinomas

Melanocytic nevi

Rombo syndrome

Xeroderma pigmentosa (XP) (p. 174)

Laboratory Data

Skin biopsy

Skeletal surveys of skull, maxilla, mandible, ribs, vertebrae

Management

Referral to dentist/oral surgeon

Referral to dermatologist/Moh’s surgeon—surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage with/without general anesthesia, topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod; frequent cutaneous examinations

Oral retinoids—suppression of new BCCs

Avoid radiotherapy/x-rays—induces new BCCs

Sun avoidance, broad-spectrum sunscreen, protective clothing

Referral to orthopedist, neurologist, ophthalmologist

Prognosis

Normal life span if BCCs treated early on and no other malignancies develop; close surveillance with physician throughout life; disfiguring scars may create psychosocial problems

Clinical Pearls

The syndrome is caused by gene defects that regulate growth and differentiation; mutations in the PTCH gene impair the PTCH protein inhibition of SMOOTHENED (SMO), a transmembrane protein. SMOs active signaling contributes to tumor formation … Clues to the diagnosis in early life include a family history, frontal bossing, and hypertelorism … Cleft lip and palate may be associated … BCCs begin in early childhood, and are often small, banal appearing monomorphic, brown, smooth dome shaped papules, very acrochordon-like, and not looking like typical adult BCC’s at all … Learning difficulties are common … A pediatric dentist should be part of the care team … Photoprotection is important, and should include sunprotective garments, hats, and broad-spectrum sunscreens … X-rays and radiotherapy should be avoided … Consider topical imiquimod as a treatment option … LE

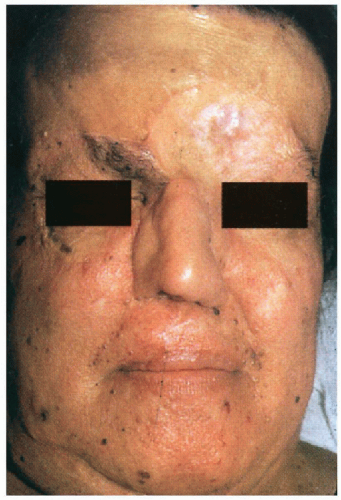

5.1. Pigmented facial basal cell carcinomas with post-surgical scars and glabellar graft. (5) |

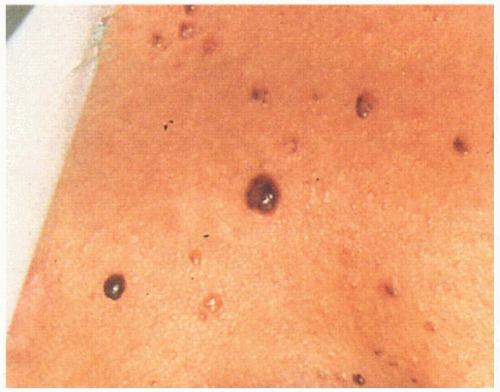

5.2. Multiple tan-brown basal cell carcinomas on patient’s back. (5) |

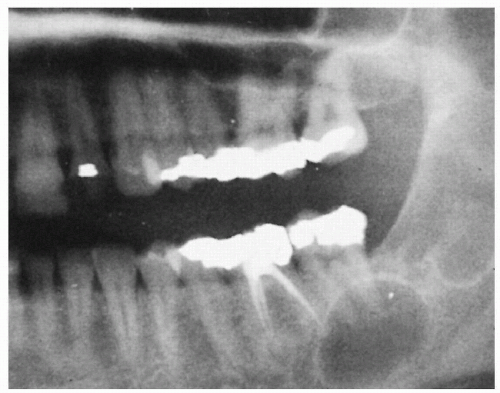

5.3. Large jaw cysts in maxilla and mandible. (5) |

|

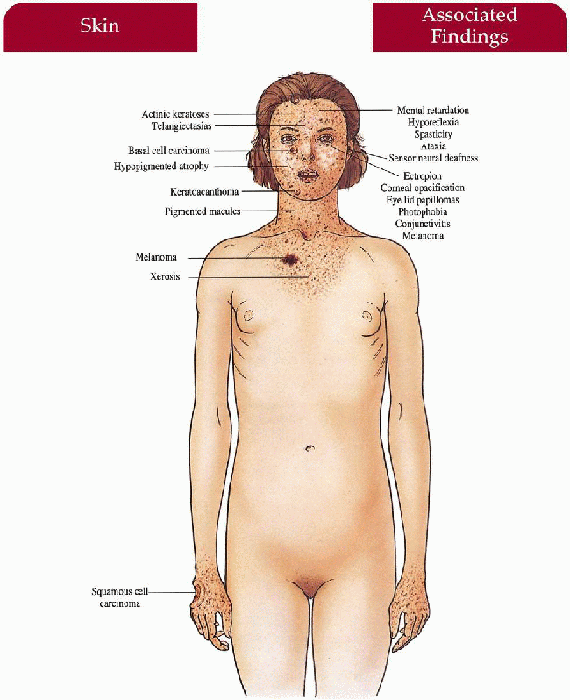

Xeroderma Pigmentosum

Inheritance

Autosomal recessive

XPA gene encodes DNA damage binding protein 1 (DDB1) gene on 9q22

XPB gene encodes excision-repair cross-complementing 3 (ERCC3) gene on 2q21

XPC gene encodes endonuclease on 3p25

XPD gene encodes ERCC2 on 19q13

XPE gene encodes DDB2 on 11p12

XPF gene encodes ERCC4 on 16p13

XPG gene encodes endonuclease on 13q33

XPV (Variant) gene encodes polymerase η on 6p21

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA analysis

UDS (unscheduled DNA synthesis) assay on cultured amniotic fluid cells

Incidence

1:1,000,000 in the United States; 1:40,000 in Japan; M=F

XPA, C, and V comprise 75% of all patients

XPA—most common form in Japan, over 90% with identical single base substitution mutation; skin with mild-severe neurologic manifestations

XPB—rare in the United States; skin and neurologic; association with Cockayne syndrome, trichothiodystrophy

XPC—most common form in the United States, rare in Japan; skin without neurologic manifestations

XPD—moderate frequency; association with trichothiodystrophy and XP-Cockayne complex, skin and neurologic manifestations

XPE—rare; mild skin without neurologic manifestations

XPF—moderate rare; most seen in Japan; skin without neurologic manifestations

XPG—extremely rare; association with Cockayne, skin with Cockayne-like neurologic manifestations

XPV—approximately 30% of all cases; United States, Europe, Japan; mild-severe skin without neurologic manifestations

Age of Presentation

First few years of life

Pathogenesis

Mutations in genes encoding DNA repair enzymes (DNA helicase, endonuclease, or DNA damage-binding protein) leads to defective DNA excision repair upon exposure to ultraviolet radiation; defective postreplication repair in XPV group

Complementation groups (total of 8), based on correction of reduced post-UV UDS after fusion of skin fibroblasts from two different patients, have distinct clinical characteristics, frequency and distribution

Key Features

Skin (severity may vary with different complementation groups)

Infancy

Acute sun sensitivity with sunburn-like reaction (erythema, inflammation, bullae)

First Years of Life

Childhood/adolescence (listed in order of appearance)—pigmented macules, achromic macules, and telangiectasias in photodistribution; dry, scaly, atrophic, with narrowing of mouth and nares; actinic keratoses, keratoacanthomas; 1,000-fold increased risk for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma

Eyes

Progressive symptomatology with photophobia, conjunctivitis, telangiectasia and pigmentation of lid and conjunctiva; ectropion, corneal vascularization, opacification; benign lid papillomas; BCC, malignant melanoma

Neurologic (20% of cases—most in XPA and XPD)

Progressive neurologic degeneration with mental retardation, sensorineural deafness; with/without microcephaly, hyporeflexia, spasticity, ataxia

Differential Diagnosis

Laboratory Data

DNA analysis

UDS assay from cultured skin fibroblasts

Management

Referral to dermatologist—sun avoidance/limit outdoor activity to early morning, late afternoon and night; photoprotect with physical block sunscreen, long-sleeve, long pants, frogskin clothing, wide-brimmed hat, UV-blocking glasses with side shields, long hair styles

Dermatologic cancer screening every 3 months with weekly examination by informed parent

Removal of cutaneous neoplasms, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod Isotretinoin—prevention of new skin cancers

Referral to ophthalmologist—corneal protection with methylcellulose drops, soft contact lens; corneal transplantation, regular cancer screening

Referral to neurologist if symptomatic

Referral to XP support group

Prognosis

Early diagnosis with UV protection and close malignancy surveillance will prevent skin cancers; otherwise premature death at early age; UV exposure prior to diagnosis and protection may induce neoplasm; neurologic symptoms are progressive and unaffected by UV protection; severe psychosocial impact

Clinical Pearls

XP is caused by gene mutations responsible for the repair of UV-induced DNA damage, which involves recognition of damaged DNA, unwinding of the DNA by helicase, and incision and removal of injured DNA strands by endonucleases; each step has mutations associated with one or several complementation groups … Photosensitivity in infants can show up as crying on sun exposure … Families shouldn’t make their life adjustments alone; the XP support group and website www.xps.org, is invaluable in keeping “state of the art” with XP care … Sunprotective garments or UV suits, window tinting, and UV meters are important parts of care, along with constant broad-spectrum sunscreen, to be worn inside and out … Children may be tutored at home, although we have been able to accommodate classrooms with UV filters and set-up special programs … Consider developmental delay, and refer early for evaluation and management … Vigilant cancer screening is crucial, and serial photography is very useful to track changing skin lesions … “Camp Sundown” is a must—it is a camp dedicated to sun-sensitive children and their families … LE

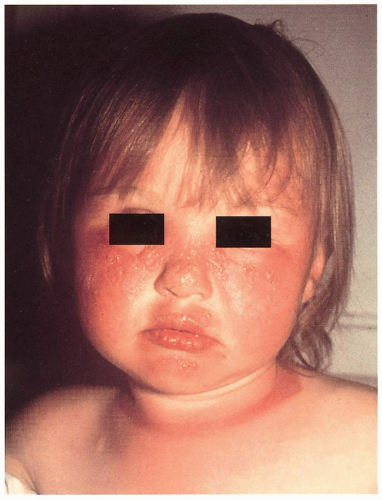

5.4. Photodistributed bullae, erythema, and inflammation in girl with XP. Note sharp cut-off of eruption on exposed neck. (66) |

5.5. Destructive cutaneous carcinomas and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in this unfortunate terminal boy. (20) |

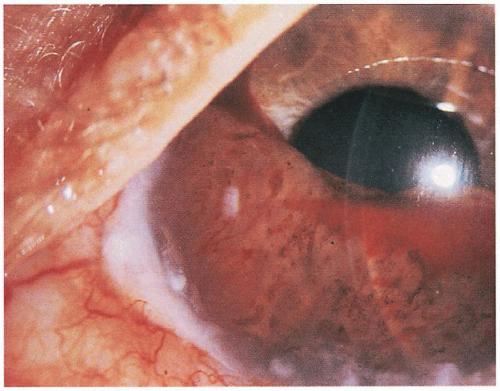

5.6. Iris melanoma and blood obliterate the anterior chamber of the eye. (67) |

|

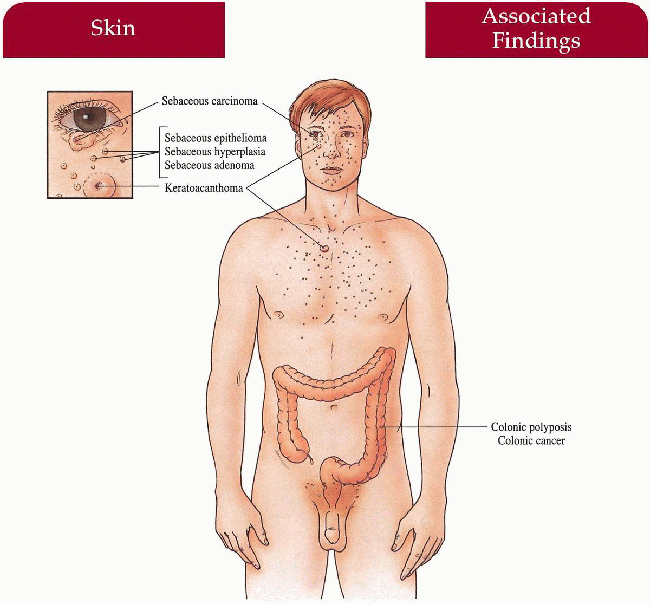

Muir-Torre Syndrome

Synonym

Torre syndrome

Torre-Muir syndrome

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant; MSH1 and MSH2 genes on 3p21 and 2p22-21, respectively

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA analysis

Incidence

At least 65 cases reported; M=F

Age of Presentation

Fifth to sixth decade of life (internal malignancies usually precede cutaneous lesions)

Pathogenesis

Mutations in MSH2 (most common) and MSH1, DNA mismatch repair genes, produces phenotype; syndrome is linked to the Lynch II cancer family syndrome

Key Features

Skin

Multiple sebaceous tumors: adenomas (most common), carcinomas, hyperplasias, epitheliomas, basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation Keratoacanthomas

Neoplasms

Adenocarcinoma of the colon (most common), other gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, lung, breast, and hematologic malignancies described

Laboratory Data

Skin biopsy

Endoscopy/gastrointestinal x-ray

Management

Close follow-up by internist screening for malignancy

Referral to dermatologist

Referral to gastroenterologist

Prognosis

Malignancies usually low-grade with good prognosis; may have normal life span with close surveillance and early detection of malignancy

Clinical Pearls

Ophthalmic sebaceous tumors may be a presenting sign … Sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma should prompt a trip to an internist for a screening evaluation, looking for visceral malignancies … Sebaceous hyperplasia and sebaceous epitheliomas arising witin nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn are not part of the syndrome … The associated visceral malignancies may be indolent, and detection can lead to prolonged survival … Both hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and Muir-Torre syndrome are caused by inherited DNA mismatch repair defect … Mutations in the MSH2 gene located on 2p are commonly implicated, while mutations in the MSH1 gene located on 3p, can also cause the syndrome … LE

|

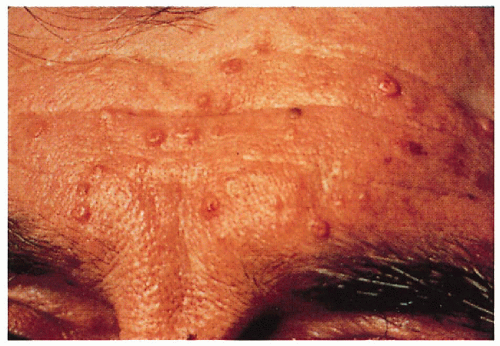

5.7. Multiple sebaceous hyperplasia and sebaceous adenomas on patient’s forehead. (68) |

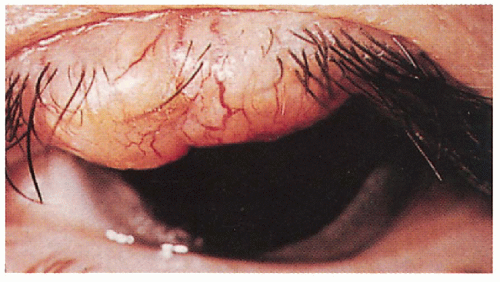

5.8. Sebaceous carcinoma of upper eyelid. (69) |

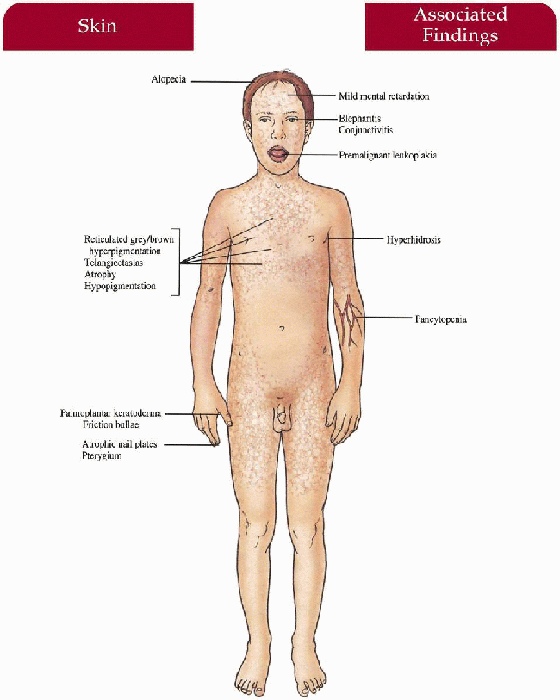

Dyskeratosis Congenita

Synonym

Zinsser-Engman-Cole syndrome

Inheritance

X-linked recessive (most common); dyskerin (DKC1) gene on Xq28; autosomal dominant and recessive patterns have been described; telomerase RNA component (TERC) gene on 3q21-q28 in autosomal dominant cases

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA analysis

Incidence

Over 100 cases reported; M:F=10:1

Age at Presentation

First decade of life (cutaneous, nail, mucosal changes)

Pathogenesis

Mutation in the DKC1 gene encoding the dyskerin protein has untoward effects on RNA nucleolar function and RNA telomerase activity with subsequent problems in cell proliferation in blood and epithelium; TERC gene mutations responsible for the RNA component of telomerase, has been implicated in autosomal dominant cases

Key Features

Skin

Reticulated gray-brown hyperpigmentation on neck, face, trunk, upper thighs; atrophy, hypopigmentation, and telangiectasias within pigmentation Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, hyperhidrosis, friction bullae, acrocyanosis

Hair

Thinning alopecia on scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes

Nails

Dystrophic with longitudinal ridges, pterygium; atrophic, or absent

Mouth

Premalignant leukoplakia of the tongue, buccal mucosa, pharynx; dental caries with early loss of teeth

Mucous Membranes

Premalignant leukoplakia of any mucosal surface

Hematologic

Fanconi’s type pancytopenia with secondary infection, hemorrhage

Eyes

Blepharitis, conjunctivitis, lacrimal duct obstruction with epiphora, ectropion

Central Nervous System

Mild to moderate mental retardation (50%)

Differential Diagnosis

Fanconi syndrome

Pachyonychia congenita (p. 294)

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (p. 238)

Chronic graft vs. host disease

Laboratory Data

Mucosal biopsy

Bone marrow biopsy

DNA analysis

Management

Referral to hematologist/oncologist—bone marrow transplantation, transfusions, oral retinoids

Referral to dermatologist, otolaryngologist, gastroenterologist, ophthalmologist

Counsel against excessive sun exposure, smoking

Prognosis

Death usually in 20s to 30s secondary to malignancy (usually squamous cell carcinoma), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or opportunistic infection

Clinical Pearls

Dyskeratosis congenita is caused by inherited defects in the telomerase complex … Autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita is associated with mutations in the RNA component of telomerase, hTERC, while X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in the gene encoding dyskerin, a protein implicated in both telomerase function and ribosomal RNA processing … X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is clearly the most common … X-linked recessive and autosomal recessive cases have a high incidence of nail dystrophy, skin changes and leukoplakia, with earlier presentation (median is approximately 15 years) … Autosomal dominant cases are usually milder, and may present later (median age at diagnosis, 28 years) … Some patients may be thought to have twenty-nail dystrophy; pigmentary and mucosal changes are sufficient to make the differentiation … Bone marrow dysfunction can be the first manifestation … Mucosal surfaces should be followed carefully with liberal biopsies of any worrisome changes … Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is the standard treatment of bone marrow complications; nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens may be more successful. LE

5.9. Poikilodermatous changes in the axilla extending on to arm. (1) |

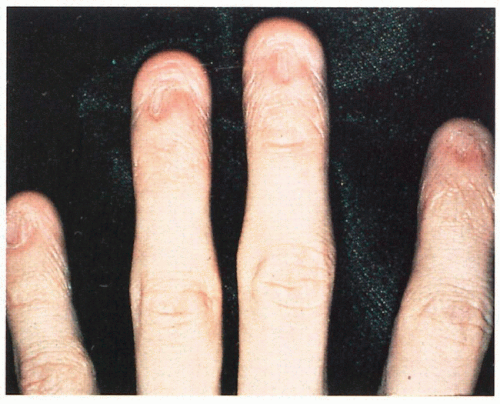

5.10. Dystrophic and absent nails. (1) |

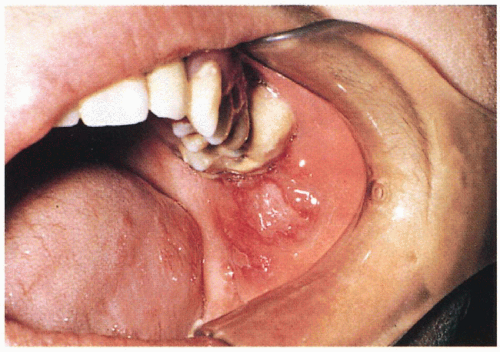

5.11. Premalignant leukoplakia of the buccal mucosa. (70) |

|

Gardner Syndrome

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant; adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene on 5q21-22

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA analysis

Incidence

Approximately 1:14,000; M=F

Age at Presentation

Infancy to early childhood (bone, skin lesions); second to fourth decade (gastrointestinal lesions)

Pathogenesis

Mutations in APC, a tumor suppressor gene that regulates B-catenin, an adherens junction protein controlling cell growth and early embryonic axis formation, promotes tumor formation; high dietary fat may play a role in patients with the genetic defect

Key Features

Skin

Epidermoid cysts—increased on head and neck; may have unusual location on toe, scalp, shin

Fibromas

Musculoskeletal

Osteomas—maxilla, mandible, other skull bones; small, multiple

Gastrointestinal

Polyposis with high predisposition to malignant adenocarcinoma; most common in colon/rectum

Desmoid tumors—postabdominal surgery; uteral or intestinal obstruction

Eyes

Congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE)—congenital marker for diagnosis

Teeth

Odontomas, supernumerary teeth

Differential Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree