Disorders of Porphyrin Metabolism

Vincent DeLeo M.D.

Clinical Pearls

(VD)

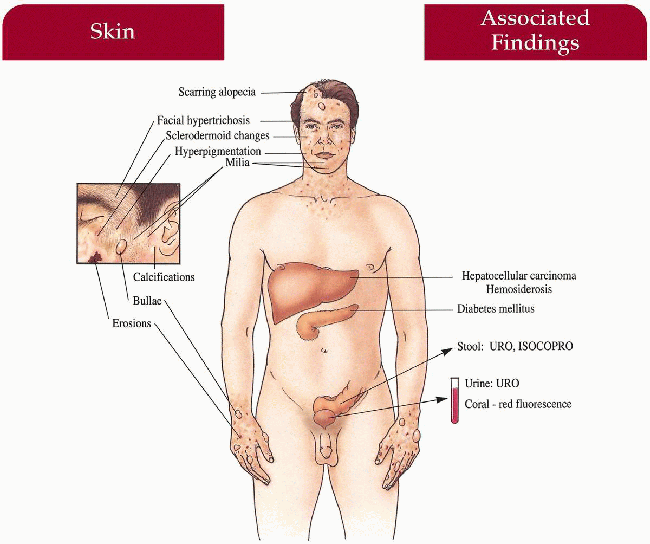

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda (PCT)

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant; Uroporphyrinogen (UROGEN) decarboxylase gene on 1p34—less common (20% of cases)

Sporadic/acquired—more common

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA analysis in familial cases

Incidence

Most common porphyria; approximately 1:25,000 in North America; M=F

Age at Presentation

Usually third to fourth decade of life; some familial patients in first decade of life

Pathogenesis

UROGEN decarboxylase gene mutation leads to UROGEN decarboxylase deficiency in erythrocytes, hepatocytes, and 50% of all tissues in familial form; deficient enzyme in hepatocytes in sporadic form

Increased uroporphyrin (URO) in skin leads to photosensitization after absorbing light energy in soret band (400-410 nm)

Alcohol, estrogen, hepatic tumors precipitate all acquired forms and may unmask familial cases

Key Features

Skin

Delayed-type photosensitivity with bullae, erosions, skin fragility, facial hypertrichosis, hyperpigmentation; late changes include scarring, milia, sclerodermoid changes, subcutaneous calcification, alopecia

Gastrointestinal

Hepatocellular carcinoma (rare)

Liver hemosiderosis

Endocrine

Diabetes mellitus

Differential Diagnosis

Variegate porphyria (VP; p. 218)

Pseudoporphyria

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

Hereditary coproporphyria (p. 221)

Laboratory Data

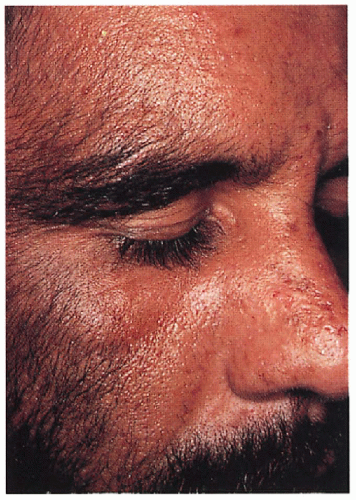

Plasma porphyrin level and fluorescence spectrum—24-hour urine porphyrin level (≠URO) complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests, iron level, hepatitis panel, liver scan; in-office urine screen—coral pink fluorescence with Wood’s light (high number of false-negatives)

Management

Phlebotomy—1 unit every 2 to 4 weeks until hemoglobin (Hb) 11 g/dL, hematocrit (Hct) 35

Antimalarials (low dose)

Eliminate alcohol, estrogen, iron exposure

Sun protection/physical-block sunscreens

Referral to dermatologist, internist, gastroenterologist

Prognosis

Normal life span with clinical and biochemical remission achievable with treatment; premature death with hepatocellular carcinoma

Clinical Pearls

I refer most of my patients to a hepatologist for work-up … Urine fluorescence in the office is a fun test, but certainly not an adequate screen given high number of false-negatives … Plasma porphyrin screens are useful in following patients therapeutically but I have had difficulty recently with plasma porphyrin analysis from the major labs around the country, so I am sticking to urine for follow-up … Some studies have shown extremely high levels of hepatitis C in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) … I get a hepatitis panel … I recommend titanium dioxide or mexoryl containing sunscreens … Women usually have electrolysis or use depilatories for the hypertrichosis … First line therapy is phlebotomy as an outpatient if there are no contraindications … Clinical response lags behind biochemical response … I’ve taken care of at least 30 patients, and I’ve never seen a failure with phlebotomy … There is no evidence suggesting that by simply having PCT leads to liver damage … I would want my residents to know how to differentiate VP from PCT… They can have identical cutaneous findings … Once you have a positive porphyrin screen, you must rule out a seizure history, and check the ratio of URO to COPRO in the urine… In PCT, 8:1; in VP, 1:1 or COPRO > URO. VD

|

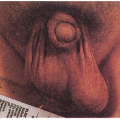

7.1. Facial hypertrichosis with erosions and scarring on nose. (5) |

7.2. Urine porphyrin screen-coralpink fluorescence with Wood’s light. (5) |

Variegate Porphyria (VP)

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant; protoporphyrinogen (PROTOGEN) oxidase gene on 1q22; severe forms associated with hemochromatosis gene on 6p21

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA analysis

Incidence

Most common in South Africa—1:330 in white population

Elsewhere approximately 1:50,000 to 100,000; M=F

Age at Presentation

Usually begins after puberty in second to third decade of life

Pathogenesis

Mutation in PROTOGEN oxidase gene causes a 50% decrease in PROTOGEN oxidase activity

Acute attacks precipitated by drugs (barbiturates, estrogen, griseofulvin, sulfonamides), infection, fever, alcohol, pregnancy, decreased caloric intake Increased Δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) synthetase with attacks

Key Features

Skin

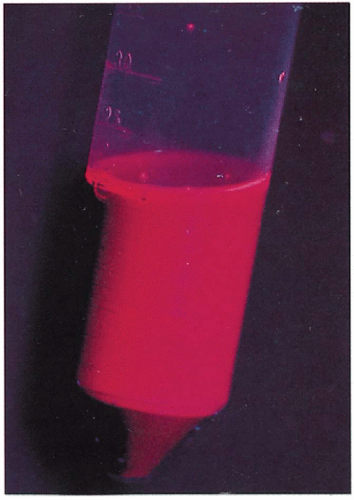

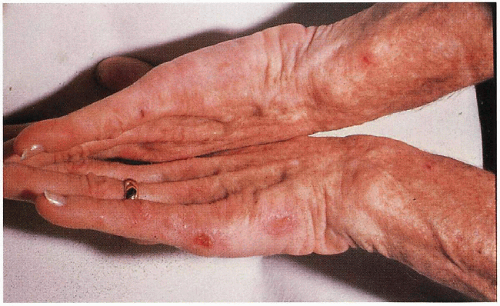

Indentical to PCT with bullae, erosions, skin fragility, scarrring, millia, hypertrichosis, hyperpigmentation on photodistributed face, neck, and dorsum of hands

Acute Attacks (i.e., Acute Intermittent Porphyria and Hereditary Coproporphyra) Gastrointestinal

Colicky abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation

Central Nervous System

Peripheral neuropathy with pain, weakness, paralysis; confusional state, anxiety, depression, delerium, seizures, coma

Cardiovascular

Tachycardia, hypertension

Differential Diagnosis

Porphyria cutanea tarda (p. 216)

Acute intermittent porphyria (AIP; p. 220)

Hereditary coproporphyria (HCP; p. 221)

Laboratory Data

Plasma porphyrin level

Plasma porphyrin fluorescence spectrum—626 nm is diagnostic

Twenty-four-hour urine porphyrin levels—coproporphyrin = or > uroporphyrin

Urinary ALA and porphobillinogen (PBG) levels increased during attacks

Fecal porphyrin levels—markedly elevated; protoporphyrin > coproporphyrin

Management

Glucose loading, hematin infusion during attacks

Avoid drug precipitators, severe dieting

Referral to dermatologist—opaque sunscreens, topical antibiotics, β-carotene

Referral to neurologist—antiseizure medication, pain control

Referral to nutritionist—small carbohydrate meals to maintain glucose levels

Prognosis

Acute attacks may be life threatening and may leave residual neurologic damage

Clinical Pearls

Still most common in the Dutch Afrikaners of South Africa … 50% with combination skin and neurologic, 15% just neurologic, 35% just skin … Don’t bleed patients —you might rev up the cycle and lead to an attack … The trick is sun avoidance with titanium dioxide and mexoryl sunscreen … Need to work with neurologist who is aware of porphyria … Prior to surgery, the neurologist should talk with the anesthesiologist … Long periods of NPO (nothing by mouth) may be dangerous … Treat infection quickly … Hand patient “avoid these medications” list … Should they become pregnant?—tough question … Needs to be discussed with primary physician and obstetrician. VD

7.3. Bullae, erosions scattered on dorsum of hands in patient with variegate porphyria (VP). (5) |

7.4. Patient with variegate porphyria (VP) with bullae, erosions on toes. (5) |

Acute Intermittent Porphyria (AIP)

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant; Porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD) gene on 11q23

Prenatal Diagnosis

Amniocentesis: porphobilinogen (PBG) deaminase deficiency in cultured amniotic fluid cells

DNA analysis

Incidence

Approximately 1:66,000 worldwide; much higher in Scandinavia

M:F=1:1.5

Age at Presentation

Third to fourth decade of life

Pathogenesis

PBGD gene mutation causes a deficiency in PBGD activity

Acute attacks may be spontaneous or precipitated by drugs (see VP, p. 218), estrogen, infection, fever, decreased caloric intake, alcohol, pregnancy, menses

Increased ALA synthetase with attacks

Mechanism for attacks unknown

Key Features

Acute Attacks

Central Nervous System

Peripheral neuropathy with pain, weakness, paralysis; anxiety, depression, seizures, confusional state, delirium, coma; rarely, respiratory failure caused by paralysis

Gastrointestinal

Colicky abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation

Cardiovascular

Tachycardia, hypertension

Hematologic

Hyponatremia secondary to antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion

Differential Diagnosis

VP (p. 218)

Hereditary coproporphyria (p. 221)

Acute abdomen

Organic neurologic/psychiatric disease

Laboratory Data

Enzyme assay—decreased PBGD in red blood cells

Plasma porphyrin level and fluorescence spectrum

Twenty-four-hour or spot urine—increased ALA and porphobilinogen during and between attacks; dark, port wine-colored urine

CBC with differential (leukocytosis), chemical screen

Management

Glucose load, hematin infusion during acute attacks

Referral to neurologist—antiseizure medication, pain control

Avoid precipitators

Referral to nutritionist—small carbohydrate meals to maintain glucose levels

Fluid and electrolytes monitored

Check family for carrier status with enzyme assay

Prognosis

Improved with avoidance of precipitators; acute attacks may be life threatening and leave residual neurologic deficits

Clinical Pearls

I can see these patients being labeled as having “chronic fatigue syndrome” … A lot of people end up having multiple exploratory laporatomies … They’ve seen multiple physicians including gastrointestinal, neurologic, and psychiatric … Many are thought to be crazy … Always give list of medicatoins to avoid … Pregnancy, surgical issues must be discussed with patients and their physicians … They can die from their attacks … But I don’t think it’s a high mortality rate at all … Like other seizure patients, they shouldn’t swim alone. VD

Hereditary Coproporphyria (HCP)

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant; coproporphyrinogen (COPROGEN) oxidase gene on 3q12

Prenatal Diagnosis

DNA analysis

Incidence

Rare—estimated 2 per million in Denmark; M=F; symptomatic M:F=1:2.5

Age at Presentation

Third to fourth decade of life

Pathogenesis

COPROGEN oxidase gene mutation causes the phenotype

Acute attacks precipitated by same factors as AIP and VP

Increased ALA synthetase with attacks

Key Features

Skin (approximately 30% of symptomatic patients)

Laboratory Data

Plasma porphyrin level and fluorescence spectrum

Increased coproporphyrin levels in stool and urine

Increased ALA and PBG in urine during attacks only

Prognosis

Acute attacks may be life threatening; many gene carriers are asymptomatic throughout life