Hair and nails are important appendages of the skin for both protection and self-esteem. In addition to protecting us and providing tactile sensations, our hair and nails can provide valuable clues to localized disorders and systemic disease. In the 21st century, there is a thriving industry dedicated to the enhancement of these otherwise ordinary appendages. While the process of enriching our hair and adorning our nails can be beneficial in the short run, long-term use of certain products can have their own deleterious effects. This chapter will review various hair and skin abnormalities, and will demonstrate some important information that can be obtained if the keen observer knows where to look.

DISORDERS OF HAIR

Disorders involving hair loss or excess have significant social and psychological implications for men and women. Hair styles and hair care can communicate much about a person, and diseases of the hair can have a significant impact on one’s self-esteem. Understanding the anatomy and growth cycle of hair is fundamental to understanding the causes of hair growth abnormalities. In this section, we will discuss how to recognize disorders involving both hair loss and hair excess. Reduced eyelash growth is discussed in chapter 23.

Types of Hair

Hair follicles differentiate and produce three different types of hair: lanugo, vellus, and terminal hairs. Around the 12th week, the embryo develops lanugo hair, which is short, soft, and nonpigmented, over the entire body. This immature hair is shed about 1 month before birth and is replaced with vellus and terminal hairs. Vellus hair is relatively nonpigmented and is not associated with a sebaceous gland. Terminal hairs cover the head and often arms, legs, and other parts of the body and are associated with sebaceous glands.

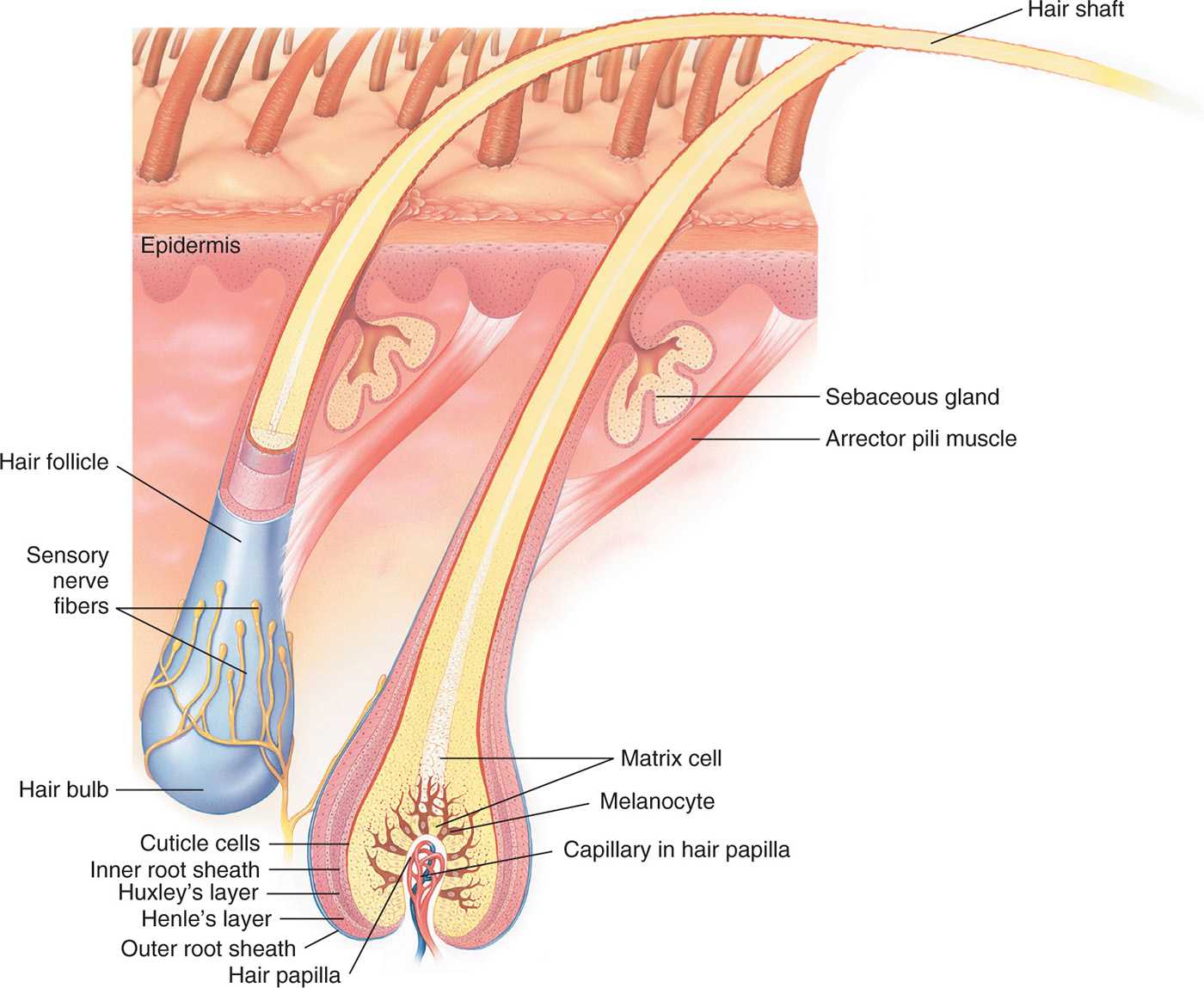

Hair has two separate structures that work together, the follicle and the hair shaft. The inferior portion of the follicle includes the hair bulb and the dermal papillae from which the hair shaft is formed and is rooted in the subcutaneous fat. The emerging hair shaft consists of an outer cuticle which is tightly compacted to support the cortex, and the interior of the follicle with rapidly dividing and growing cells. Melanocytes in the hair bulb give the cortex its color. Each hair shaft has a tapered tip, and the hair is lubricated by the sebum produced by the sebaceous gland (Figure 14-1).

Hair Growth Cycle

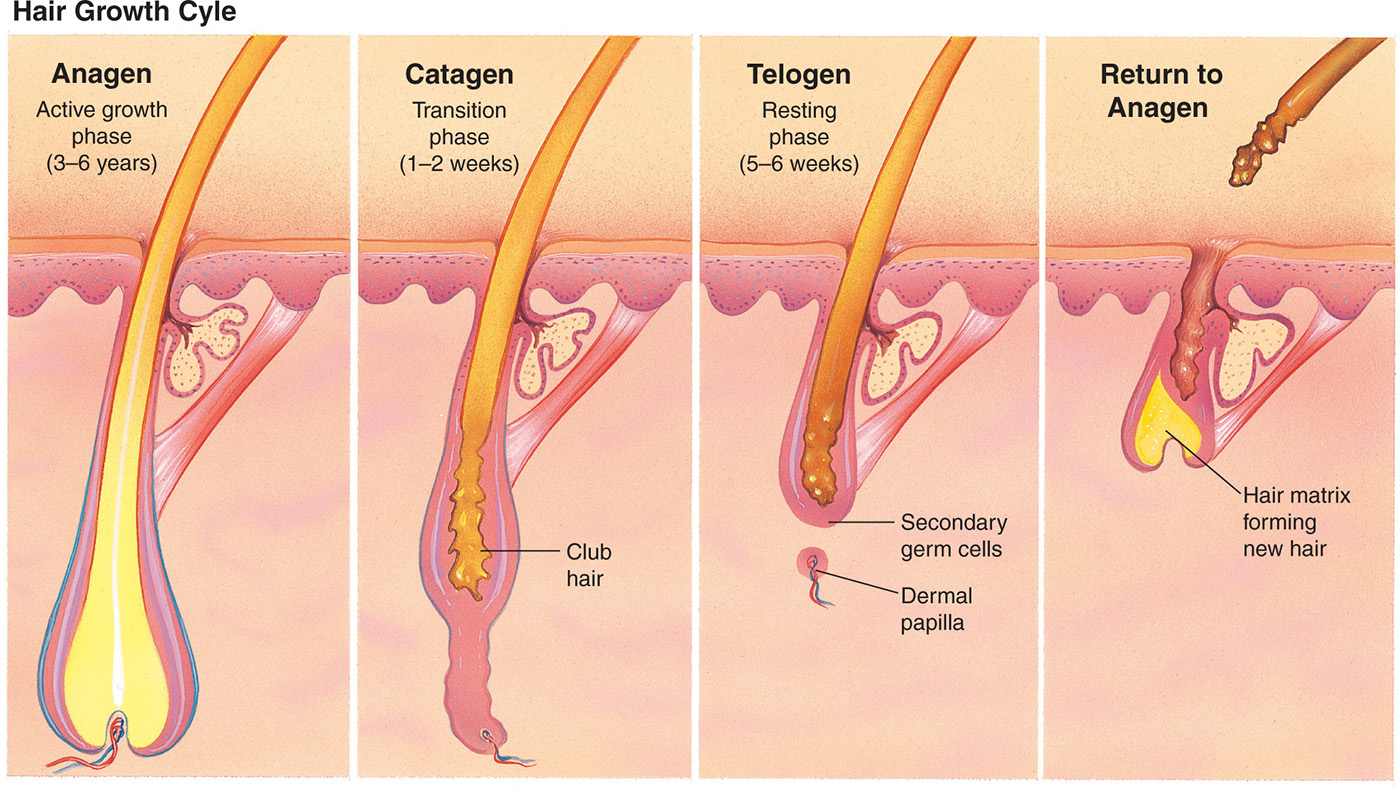

The cycle of hair growth has three phases: anagen, catagen, and telogen. The anagen phase is the growth phase, which occurs when the cells in the bulb and the dermal papilla are actively dividing and forming a new hair shaft. Normally, 90% to 95% of hairs are in the anagen phase, which can last 2 to 6 years and enables some to achieve hair of extraordinary lengths. The anagen phase, which is genetically determined, is longest on the scalp and much shorter on other areas such as eyelashes and brows.

The catagen phase is a short transitional phase lasting a few days to weeks, with only a few hairs (<1%) at any given time. During this phase, the hair bulb goes through an involution and the outer sheath shrinks and detaches from the follicle but attaches to the hair shaft to develop a tighter club hair. The inferior portion of the hair shaft detaches from the dermal papilla, comes to rest at the level of the erector pili muscle, and is eventually pushed out. The dermal papilla rests under the hair follicle bulge before it starts to reform a new hair shaft.

The telogen phase is the resting phase and lasts 2 to 3 months, accounting for the average loss of 50 to 100 hairs daily. In many animals, telogen and shedding are seasonal but in humans it is random (Figure 14-2).

HAIR LOSS

Alopecia, or hair loss, can be divided into two main categories: scarring (cicatricial) and nonscarring (noncicatricial). Nonscarring alopecia is seen more commonly and comprises patchy hair loss, thinning, or shedding without any scarring features. Scarring alopecia is less common and associated with an inflammatory or infectious etiology. It is characterized by an area of complete destruction of the follicles with resulting scar formation. The hair loss is most often permanent and irreversible. Each of these categories can be further divided into diffuse or localized (patchy) hair loss. These four characteristics of alopecia are important clues for an accurate assessment and differential diagnoses (Table 14-1).

As with most medical problems, a good assessment of a patient with the complaint of hair loss begins with a complete history and physical examination. History alone is sometimes sufficient to determine the diagnosis, especially in nonscarring alopecia (Table 14-2). A physical examination should begin by assessing the entire scalp surface and the hair shaft. Other hair-bearing areas, such as eyebrows, eyelashes, beard and moustache, axillae, genitals, and extremities, should be inspected if indicated. As mentioned, specific characteristics of the alopecia can guide the clinician to develop a differential diagnoses and appropriate diagnostics. There are a few diagnostics needed in the evaluation of any hair loss (Box 14-1).

NONSCARRING ALOPECIA—DIFFUSE

Male Pattern Hair Loss

Patterned hair loss in men (MPHL) is viewed by some as inevitable and tolerable, while others find it unacceptable. MPHL is the most common cause of alopecia in men, with the highest prevalence in Caucasian males, having an onset before age 50, but usually showing signs of thinning before the age of 30 years. There is higher incidence of benign prostatic hypertrophy in patients with MPHL.

FIG. 14-1. Anatomy of hair.

FIG. 14-2. Hair growth cycle.

Characteristics of Alopecia for Differential Diagnosis |

TYPE | DIFFUSE | PATCHY/FOCAL |

Nonscarring | Androgenetic alopecia (thinning) Telogen effluvium (shedding) Anagen effluvium | AA Trichotillomania Tinea capitis or infection* |

Scarring | Lichen planopilaris Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus Dissecting cellulitis | Discoid lupus CCCA Acne keloidalis Traction alopecia |

*If not treated early, can result in scarring alopecia.

Pathophysiology

MPHL is caused by a genetically predetermined influence of androgens on hair follicles. Normally, 5α-reductase converts testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone and increases scalp and beard growth in the male adolescent. Later in life, however, the dihydrotestosterone binds to the androgen receptor in the follicle, causing a shortening of the anagen cycle and miniaturization of hair follicles. The result is finer, shorter, and fewer hairs that can ultimately lead to baldness.

Clinical presentation

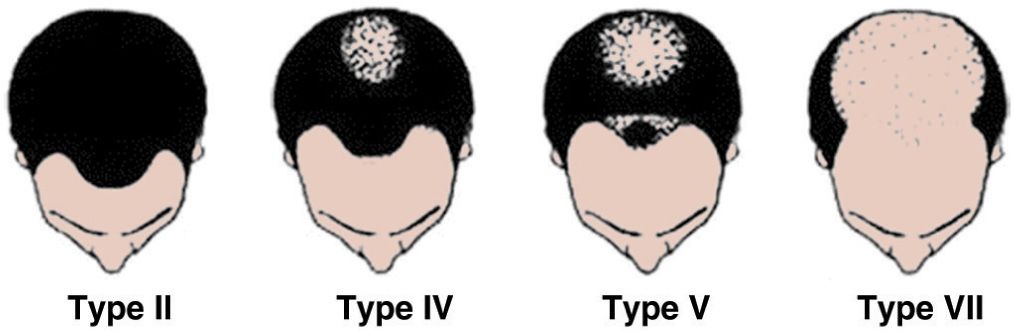

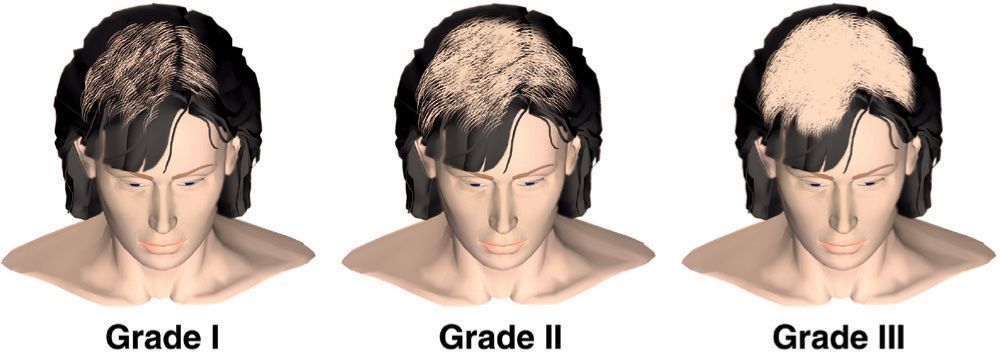

Most often it is not difficult to diagnose MPHL. Hair thinning and loss usually occur in the “M” distribution, affecting the bilateral temples and crown. These are considered the androgen-sensitive hair follicles. MPHL may be partial or complete and usually spares the sides and back. The Hamilton–Norwood classification is used to document and monitor the extent of hair loss. Seborrheic dermatitis is also commonly seen (Figure 14-3).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Male pattern hair loss |

• Alopecia areata (diffuse)

• Telogen or anagen effluvium

Evaluation of Hair Loss: History |

PERSONAL HISTORY | MEDICAL HISTORY | FAMILY HISTORY |

Ask the patient: • When did you first notice hair loss? • When did your hair last seem normal? • Was it sudden or gradual? • Is hair falling out (and seen in the drain or brush) or do you notice thinning (not as thick)? • Is the hair loss diffuse or patchy? • Is it only on the scalp or in other areas? • Any recent trauma, physical, or emotional? If yes, when did this occur? • What treatments have you tried? • Detailed inquiry about: • Hair care, products, styling • Use of tools (hot combs), relaxers or dyes, heat, use of extensions or weaves, and styling that pulls or binds (corn rows, ponytails, etc.) | List medications, especially new medications • Consider undeclared use of anabolic cortico steroids • Corticosteroids is one word use of prescription or over-the-counter herbs or supplements • Recent illness, surgeries, anesthesia, weight loss (diets) • Thyroid disease • Ob/gyn issues: menstrual irregularities, infertility • Skin conditions: acne, hirsutism, etc. | Balding male or female family members Thyroid disease |

FIG. 14-3. Hamilton–Norward classification of male pattern baldness.

Management

MPHL is a cosmetic concern where both medical and surgical treatments are available. Determining how aggressive your patient wants to be is important when suggesting therapies. Medical therapies do not cure, but instead slow the progression and promote a thicker hair shaft. They also cannot grow hair on bald areas void of hair follicle. Minoxidil 2% and 5% topical solutions have been used for many years, however. Oral minoxidil was originally used as an antihypertensive drug for vasodilatory effects. But it also increases the anagen cycle and decreases miniaturization. Good results have been achieved using the 5% solution b.i.d. but will not achieve noticeable results for many months, and it must be continued for the long term. Minoxidil is applied to the entire affected area (dry scalp) twice daily and should remain on for at least 1 hour. When applied at night, it should be 2 hours before bedtime to prevent transfer of the product to the pillowcase. Touching the face during sleep could result in an increase of facial hair. The most common side effect is irritation and itching. It is more efficacious in young males with new onset of hair loss on the vertex and less effective in bitemporal loss.

Greater success has been seen with finasteride, a 5α-reductase antagonist, which blocks the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, slowing the binding to androgen receptors and therefore slowing miniaturization. It is approved for use in males aged 18 years and older, dosed at 1 mg per day, and must be given for 3 to 6 months before success is determined. It is successful 70% to 80% of the time and should be continued indefinitely. Although there is no supporting evidence, many men use both oral and topical therapies concurrently. Patients should be advised that finasteride may decrease their libido or cause impotence and issues with ejaculation. Most symptoms subside upon discontinuance of the drug.

Important Findings in Patients with Hair Loss |

Physical Examination

• Location and pattern of hair loss

• Diffuse or localized

• Complete loss or thinning

• Hair texture, length, and color

• Presence of scarring

• Presence of erythema, pustules, scale, or abnormal pigmentation

• Nail findings

• Acne or hirsutism

• Patient affect and behaviors (i.e., anxiety)

Diagnostics (if indicated)

Part Width Test

Performed with the patient’s head tipped forward, begin by parting the hair on the frontal scalp with a comb (if available) or the wooden end of a cotton-tipped applicator. Observe the width of the part and then compare the part width of the crown with many parallel parts on the temporal areas and occipital areas. Check to see if the part width is consistent in all sections.

Hair Pull Test

Consists of grasping 20 or so hairs on the crown. Pull gently but with enough pressure to tent the scalp and slide the fingers along the hair shafts distally to pull some hairs out. Examine the bulbs of the extracted hairs with a magnifier. Telogen hairs will appear as white bulbs at the end of the shaft. Fewer than six bulbs is considered normal (5%–10%). This may need to be repeated on two to three additional areas.

Punch Biopsy

Aids in the diagnosis of scarring alopecias. Indicated if the diagnosis is uncertain, the patient has multiple characteristics or failure to respond to treatment. A 4-mm (not any smaller) punch biopsy should be performed on the scalp area affected and close to the active edge of the scalp area. Be sure to get a sample of hair follicles and punch deep enough to get subcutaneous tissue where the bulb of anagen hairs will be located. Many clinicians will send two specimens, with one indicated for vertical sectioning, allowing for a good examination of the hair bulb. The specimen should be labeled for hair evaluation. Avoid specimens from the bitemporal area, which normally have some miniaturized hairs.

Laboratory Diagnostics

• Not often necessary but are guided by specific differential diagnoses.

• Fungal cultures can help to confirm tinea.

• Serologies help identify underlying disease causing alopecia: complete blood count and ferritin (iron-deficiency anemia); RPR (syphilis); antinuclear antibodies (autoimmune diseases); and TSH, T4, and thyroid antibodies (hypothyroidism).

• In women, serum testosterone (free and total), DHEAS, and prolactin levels (if galactorrhea is present).

• Additional hormonal studies should be done in the presence of menstrual irregularities or hormonal abnormalities.

Surgical treatments include hair transplantation and scalp reduction. These are generally available through dermatology surgeons or plastic surgeons skilled in this fine art. Hair weaves are noninvasive techniques that use real hair to form a matrix which is then attached to the remaining short hairs. These treatments are commercially available through hair restorative groups or persons skilled in the process of creating wigs. Patients should be careful to avoid any harsh treatments on the hair or scalp and treat any scalp conditions like seborrheic dermatitis.

Female Pattern Hair Loss

Patterned hair loss in women (FPHL) is not as well understood as its male counterpart, but it is thought to be primarily genetic with at least one first-degree male relative with androgenic hair loss. It is a diffuse and nonscarring process. The onset for women is during their 20s or late 40s and can be perimenopausal. A common presenting complaint is “I can see my scalp” or “I am getting a sunburn on my scalp.”

Pathophysiology

Because the pathogenesis of FPHL is not well understood, the term androgenetic is no longer accurate, although still often used. There is little evidence to support the theory that androgen levels were increased; furthermore, most women with FPHL lack any other signs of hyperandrogenism. Estrogen protects against hair loss and therefore FPHL is seen to some degree in all women who are postmenopausal.

Clinical presentation

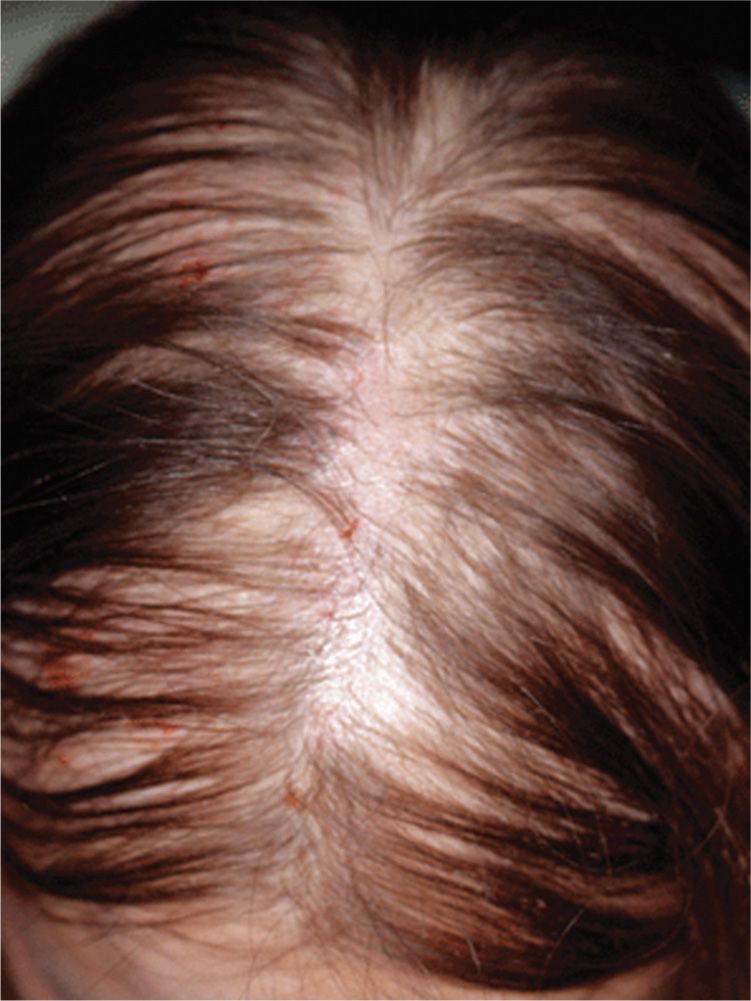

The presenting complaint by patients is usually for generalized hair loss or thinning, while on examination hair changes are most visible on the crown. Excess shedding is not a symptom; lack of growth leading to thinning is the problem. The part width is increased when compared to the temporal and occipital areas and is often described as a Christmas tree pattern (Figure 14-4). There can be significant miniaturization and thinning of the crown, but the frontal border of hair is always preserved (Figure 14-5).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Female pattern hair loss |

• Telogen effluvium (acute and chronic)

• Diffuse alopecia areata

FIG. 14-4. Female pattern hair loss begins with widening central part and diffuse thinning.

FIG. 14-5. Ludwig classification of female pattern hair loss. Note the retention of the frontal hairline despite the increasing severity of hair loss.

Management

The only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved treatment for FPHL is minoxidil 2% solution. Many clinicians start with a 2% solution twice daily to minimize side effects and increase to a 5% solution (off-label) if there has been no improvement after 6 months. The 5% preparation of minoxidil is more effective but also has higher risk of hypertrichosis on the malar prominences and forehead. The application and side effects are the same as with men. Most women with FPHL do not have hyperandrogenism; therefore, use of antiandrogens is neither indicated nor supported by any evidence. However, clinicians sometimes treat FPHL with oral contraceptives, spironolactone, or finasteride based on some anecdotal reports of success. Minoxidil is contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation.

Cosmetic aids such as powdered dyes or lotions can camouflage the scalp, making the hair loss less obvious. Wigs are often used in addition to hair extensions and weaves. Surgical therapies are available.

Referral and consultation

If DHEAS or testosterone levels are elevated and abnormal, a referral to an endocrinologist may be necessary.

Prognosis and complications

FPHL is a lifelong problem that does not have physical complications, but can have a significant psychosocial impact on patients.

Patient education and follow-up

Follow-up is generally not needed, and patients can continue use of Minoxidil indefinitely. However, sudden changes or rapidly advancing alopecia should prompt a reevaluation with the clinician.

Telogen Effluvium

Telogen effluvium (TE) is a nonscarring, diffuse hair loss, which causes women significant psychological stress. It is commonly seen in both primary care and dermatology offices.

Pathophysiology

TE occurs when there is an alteration in the hair growth cycle, primarily anagen and telogen phases. It is usually acute, but there are some cases of chronic TE occuring in middle-aged women. TE can be triggered by a significant emotional event or physical trauma in a patient’s life. This can include illness, fever, hospitalization, surgery, childbirth, death of a loved one, or divorce. The growth cycle of the anagen hair is abruptly terminated, and a large number of follicles advance to the telogen phase. The result is shedding hairs at a higher than normal rate. In most cases of TE, less than half of the follicles are affected.

Medications that can cause TE include warfarin, isotretinoin, β-blockers, and ace inhibitors. It is not necessary to discontinue these medications as the hair growth cycle will eventually adjust itself back to normal. Discontinuing estrogen therapy or oral contraceptives can also cause a transient TE, and restarting therapy is not necessary.

Clinical presentation

Examination of a scalp with TE does not reveal noticeable abnormalities. There should be no erythema or scale and typically no areas of complete loss. Oftentimes, the density of the hair appears normal to the examiner, yet the patient gives a history of a significant change. Patients complain, “I am losing my hair” or “I am noticing a lot of hair in the shower drain.” The key is that patients report increased shedding. These patients begin to shampoo less often in hope of preserving hair. They fail to realize that the average number of hairs lost daily is more evident on days they shampoo.