Micro/macrocystic lymphatic malformation

19.6 %

Non-eponymous combined vascular malformation

13.0 %

Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome

10.9 %

Capillary malformation

10.9 %

Hemihypertrophy

8.7 %

Posttraumatic swelling

8.7 %

Parkes Weber syndrome

6.5 %

Lipedema

6.5 %

Venous malformation

4.3 %

Rheumatologic disease

4.3 %

Infantile hemangioma

2.2 %

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

2.2 %

Lipofibromatosis

2.2 %

Table 16.2

Diagnosis of patients referred to a lymphedema center with an enlarged extremity (n = 217)

Total (%) | <21 years (n = 61) (%) | >21 years (n = 156) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Lymphedema | 75 | 90 | 69 |

Venous stasis | 7 | 0 | 10 |

Lipedema | 6 | 0 | 8 |

Obesity | 4 | 0 | 6 |

Injury | 4 | 4 | 4 |

Rheumatological disease | 3 | 3 | 3 |

Vascular malformation | 1 | 3 | 0 |

Accurately diagnosing a patient with lymphedema is necessary in order to be able to counsel the individual and family about the prognosis and treatment of the disease. As we previously have shown for infantile hemangioma, if a disease is called by the incorrect name, the patient is more likely to receive erroneous (and potentially harmful) treatment [1]. Consequently, the burden is on the health care provider to determine whether an individual with an overgrown extremity does, in fact, have lymphedema. The prognosis and management of lymphedema can be very different than for other conditions. For example, a patient with diffuse capillary malformation is not at risk for infection and may have a leg-length discrepancy (in contrast to an individual with lymphedema).

Diagnosis of Lymphedema

History

Ninety percent of patients with lymphedema may be diagnosed by history and physical examination. In the pediatric population, at least 97 % of children have idiopathic, primary disease (Fig. 16.1); only 3 % have secondary lymphedema from injury to axillary or inguinal lymph nodes [4]. Primary lymphedema affects approximately 1/100,000 children [5]. Boys are most likely to present during infancy and have bilateral lower extremity disease [4]. Girls usually develop swelling in adolescence; typically only one lower extremity is involved [4]. Males most commonly present with lymphedema in infancy (68.0 %), compared to childhood (12.0 %) or adolescence (20.0 %) [4]. The median age when males and females develop lymphedema is <12 months and 10 years, respectively [4]. Boys and girls are equally at risk for developing primary lymphedema, and thus, the gender of the patient does not heighten the suspicion for lymphedema [4]. Idiopathic upper extremity or generalized lymphedema is rare. Children with primary lymphedema have an 11 % chance of having hereditary and/or syndromic lymphedema (e.g., Milroy, Noonan, Meige, lymphedema–distichiasis, Turner, Hennekam) [4]. If a child has a parent with lymphedema, it is very likely that the patient also has the condition because many syndromic causes of lymphedema are hereditary.

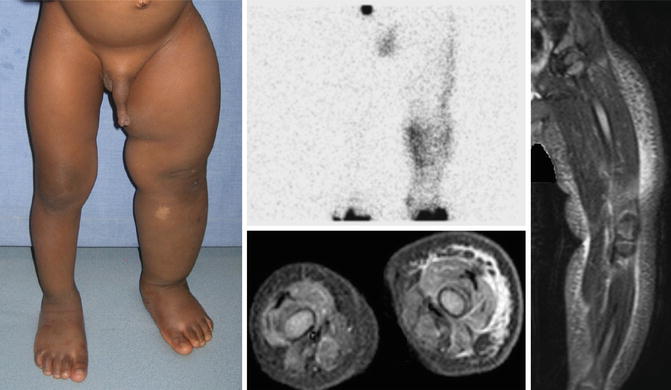

Fig. 16.1

Primary lymphedema. 2-year-old male with left lower extremity swelling since birth. Lymphoscintigram demonstrates dermal backflow and absent inguinal node drainage 2.5 h after injection. Axial T2-weighted MR with fat saturation shows a hyperintense reticular network of dilated subcutaneous channels between the dermis and fascial plane. With permission from Schook CC, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Alomari AI, Grant FD, Greene AK. Differential diagnosis of lower extremity enlargement in pediatric patients referred with a diagnosis of lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:1571–1581 © Wolters Kluwer in 2011 [2]

In the adult population, secondary lymphedema accounts for approximately 99 % of cases (Fig. 16.2). Adult-onset primary lymphedema is rare. Patients are asked about a history of injury to the axillary or inguinal nodes (e.g., lymphadenopathy, radiation, operations). If they have had a significant trauma to the axillary or inguinal nodes, then the likelihood that they have lymphedema is increased. Adults are also queried about systemic diseases (e.g., congestive heart failure, renal failure, hepatic dysfunction, rheumatological disorders) and history of extremity trauma. Patient body mass index (BMI) is recorded; if it is greater than 60, then it is probable that the individual has obesity-induced lymphedema [6, 7].

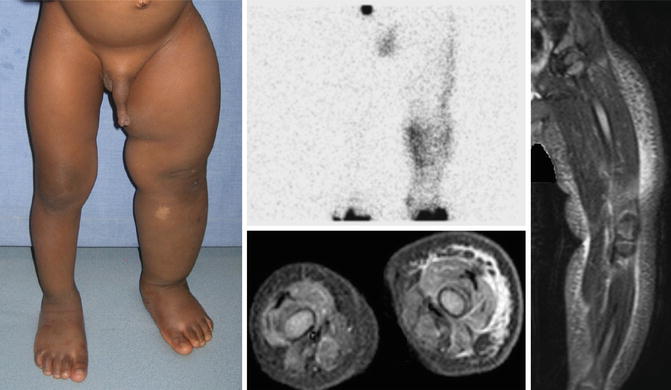

Fig. 16.2

Secondary lymphedema. Adult male with a history of right inguinal lymphadenectomy for cancer. Lymphoscintigram shows minimal drainage on the right side 1 h after injection. MRI illustrates thickening of the subcutaneous fat with edema

If a patient has a history of infections involving the extremity, then it is more likely that he/she has lymphedema because individuals with lymphedema have a significantly increased risk of infection in the affected limb. Because the most common cause of lymphedema worldwide is a parasitic infection, families are queried about a history of travel to areas endemic for filariasis. If the patient has resided in an area endemic for filariasis, then the probability that the individual has lymphedema is increased.

Physical Examination

Primary lymphedema affects an extremity in 95.7 % of children [4]. The lower limb is most often involved (91.7 %), and 9.4 % have both upper and lower extremity swelling [4]. Bilateral disease is more likely in patients presenting in infancy (62.9 %) or childhood (66.7 %), versus adolescence (30.8 %) [4]. There is no difference in bilateral lymphedema between the upper extremities (63.6 %) or lower extremities (52.9 %), or in females (49.4 %) compared to males (49.0 %) [4]. Bilateral disease is more common in patients presenting in infancy (62.9 %) or childhood (66.7 %), versus adolescence (30.8 %) [4]. Genital lymphedema occurs in 18.1 % of patients with primary lymphedema; 4.3 % of males have isolated involvement and 13.8 % have genital and lower extremity lymphedema [4]. Males are more likely than females to have genital lymphedema (36.8 % versus 4.9 %) [4].

Lymphedema almost universally affects the distal extremity and then migrates proximally. If a patient does not have distal limb swelling, it is very unlikely that he/she has lymphedema. A fairly sensitive and specific sign for lymphedema is the Stemmer sign. If the examiner is unable to pinch the skin on the dorsum of the hand or foot (positive Stemmer sign), then it is likely the patient has lymphedema [8]. Chronic swelling, inflammation, and adipose deposition cause the skin to thicken which reduces the ability to lift and pinch the integument of the distal extremity. Patients also are examined for scars in the axillary or inguinal regions, which may represent injury to lymph nodes in these regions. Lymphedema is typically a painless condition and cutaneous ulceration is uncommon. Overlying skin discoloration can occur, but is unusual. Lymphedema does not affect the underlying bone, and thus, patients do not have a leg-length discrepancy. Over time, individuals with lymphedema can develop lymphatic vesicles, usually involving the toes, which can bleed and leak lymph fluid (lymphorrhea).

Imaging

Because lymphedema easily can be confused with other causes of extremity overgrowth, we have a low threshold to obtain a lymphoscintigram to: (1) confirm or rule-out the disease, and (2) assess the degree of lymphatic dysfunction in patients who have a high likelihood of having the condition. Lymphoscintigraphy is 92 % sensitive and 100 % specific for lymphedema [9]. Although MRI and CT are non-diagnostic for lymphedema, findings consistent with the condition include: (1) subcutaneous adipose tissue overgrowth, (2) edema, (3) thickened skin, and (4) findings isolated to soft-tissue above the muscle fascia [2]. Typically, subcutaneous adipose hypertrophy and fluid findings are symmetrical and circumferential. A key finding is that lymphedema does not affect structures beneath the muscle fascia. If a patient has a normal lymphoscintigram and/or their disease involves muscle or bone, then it is very unlikely the patient has lymphedema.

Differential Diagnosis of Lymphedema

Capillary Malformation

A diffuse capillary malformation of an extremity can cause circumferential and longitudinal limb enlargement (Fig. 16.3) [4, 10]. These children have diffuse capillary malformation with overgrowth (DCMO). Capillary malformation is caused by a somatic mutation in GNAQ. Unlike lymphedema, the underlying bone is involved and patients are monitored for a leg-length discrepancy [2]. The capillary malformation causes progressive overgrowth of the underlying subcutaneous adipose tissue which generally results in circumferential and symmetrical growth. Occasionally, hypertrophy of tissues beneath the stain can be localized. Patients have normal lymphatic function by lymphoscintigraphy and do not have an increased risk of infection. Patients are managed using pulsed-dye laser to lighten the cutaneous stain, liposuction to debulk the subcutaneous adipose hypertrophy, and orthopedic procedures to address the bony overgrowth.

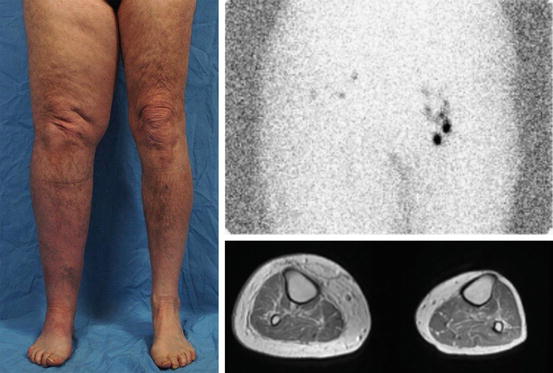

Fig. 16.3

Capillary malformation. 24-year-old female with a diffuse capillary malformation of the skin and subcutaneous adipose overgrowth of the left lower extremity. MRI shows thickening of the subcutaneous fat without edema

CLOVES Syndrome

CLOVES syndrome (Congenital Lipomatosis, Overgrowth, Vascular malformations, Epidermal nevi, and Scoliosis/Skeletal/Spinal anomalies) is a non-familial condition caused by a PIK3CA mutation. Major features include: (1) a truncal lipomatous mass, (2) a slow-flow vascular malformation (typically a capillary malformation overlying the lipomatous mass), and (3) hand/foot anomalies (increased width, macrodactyly, first web-space sandal gap) [11]. Less common findings include paraspinal fast-flow malformations, linear epidermal nevus, and hemihypertrophy. Children are at risk for developing Wilms tumor and thus require renal ultrasound examination every 3 months until they reach 8 years of age. Central and thoracic phlebectasia can cause pulmonary embolism. Extremity overgrowth is typically hemihypertrophy affecting all tissues of the extremity (skin, subcutis, muscle, and bone) (Fig. 16.4). Orthopedic consultation is obtained to determine whether a leg-length discrepancy is present. Patients may require soft-tissue debulking or amputations to facilitate shoewear and/or ambulation.

Fig. 16.4

CLOVES syndrome. In contrast to lymphedema, the right leg has asymmetrical overgrowth of all structures (skin, subcutis, muscle, and bone) and the patient has bilateral foot anomalies

Hemihypertrophy

Hemihypertrophy is the idiopathic enlargement of an area compared to the contralateral side (Fig. 16.5). It is a rare condition that is present at birth [2, 12]. All components of an extremity are overgrown (i.e., bone, muscle, subcutis, skin). Imaging studies do not exhibit pathological findings other than enlarged structures [2]. Lymphatic function and lymphoscintigraphy are normal. Hemihypertrophy is usually a diagnosis of exclusion. Because the bone may be involved, children can have a leg-length discrepancy that necessitates orthopedic intervention. Circumferential overgrowth can be improved by removing subcutaneous adipose tissue using suction-assisted lipectomy. Because patients are at risk for Wilms tumor, they must undergo renal ultrasound screening.

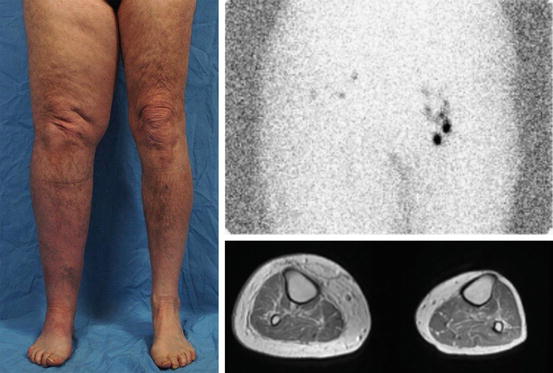

Fig. 16.5

Hemihypertrophy. 15-year-old female with right lower extremity hemihypertrophy diagnosed at birth. She was screened for Wilms tumor and had a ray amputation to facilitate her ability to wear shoes. MRI demonstrates overgrowth of the subcutaneous fat, muscle, and bone

Infantile Hemangioma

Rarely, an infantile hemangioma can be diffuse and cause overgrowth of an extremity (Fig. 16.6). These lesions are differentiated from lymphedema because they grow rapidly during the first few months of life, then stabilize, and regress after 12 months of age [13]. “Reticular” hemangioma involves the lower extremity and can be infiltrative and involve fascia or muscle [14]. These children are at risk for underlying urogenital anomalies, and thus, ultrasound and/or MRI is considered. Infantile hemangiomas may ulcerate and/or cause congestive heart failure. Large, symptomatic tumors are managed with prednisolone or propranolol. Residual telangiectasias are treated with pulsed-dye laser.

Fig. 16.6

Infantile hemangioma. 3-month-old with a reticular infantile hemangioma of the left lower extremity that appeared shortly after birth. The red appearance of the skin and rapid postnatal progression was inconsistent with lymphedema, but typical for infantile hemangioma. With permission from Schook CC, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Alomari AI, Grant FD, Greene AK. Differential diagnosis of lower extremity enlargement in pediatric patients referred with a diagnosis of lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:1571–1581 © Wolters Kluwer in 2011 [2]

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma is a rare vascular neoplasm that is locally aggressive, but does not metastasize (Fig. 16.7). It affects approximately 1/100,000 persons (similar to primary lymphedema) [15]. Sixty percent are present at birth, and 93 % are diagnosed during infancy [15]. The tumor is often diffuse, and an extremity is affected in approximately one-third of patients. The lesion slowly enlarges during the first 2 years of life and then partially regresses. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma frequently persists long-term and can cause chronic pain, stiffness, and contractures. The skin is reddish-purple, and pain is common. Seventy percent of patients have Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon (KMP) (thrombocytopenia <25,000/mm, [3] petechiae, bleeding), which is pathognomonic for the condition [15]. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma also has a lymphatic component, which stains positive for the lymphatic markers D240 and PROX1. Most patient with kaposiform hemangioendothelioma are treated to prevent life-threatening complications from Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon and to minimize long-term pain and contractures. Management includes either vincristine or sirolimus [13]. Resection is rarely possible because the tumor involves multiple tissue planes and important structures.

Fig. 16.7

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. 3-month-old with kaposiform hemangioendothelioma diagnosed by history, physical examination, and laboratory findings. The patient suffered from diffuse discoloration of the extremity, bruising, and thrombocytopenia which do not occur with lymphedema. With permission from Schook CC, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Alomari AI, Grant FD, Greene AK. Differential diagnosis of lower extremity enlargement in pediatric patients referred with a diagnosis of lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:1571–1581 © Wolters Kluwer in 2011 [2]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree