CHAPTER 10 Diagnosis and Management of the Patient with Tearing

Anatomy and function

Anatomic sites of obstruction

Normal tear drainage depends on a functioning lacrimal pump and an intact lacrimal drainage system (Figure 10-1). As you recall from Chapter 2, the tears enter the upper and lower puncta and travel in a short vertical portion of the puncta for 1 or 2 mm before entering the horizontal portion of the canaliculi. The canaliculi enter the lacrimal sac at an angle, which forms a sort of valve (called the common internal punctum). The lacrimal sac sits in the lacrimal sac fossa bounded by the anterior lacrimal crest (maxillary bone) and the posterior lacrimal crest (lacrimal bone). The sac narrows inferiorly, forming the nasolacrimal duct (membranous nasolacrimal duct). The duct passes inferiorly through a bony canal (osseous nasolacrimal duct) to open beneath the inferior turbinate into the inferior meatus of the nose. The valve of Hasner at this opening prevents retrograde flow of tears or air up into the duct from the nose. An abnormality anywhere along this path can delay or block the drainage of the tears, usually causing a tearing eye. Anatomic obstruction can occur in the canaliculi or the nasolacrimal duct.

History

The “watery” eye versus the “tearing” eye: the significance of true epiphora

The definition of true epiphora—“tears on the cheek”

What do the answers to these questions mean? The watery eye can be caused by a number of problems. Most of these problems are related to poor tear film, causing ocular irritation (or reflex tearing). There may be a subtle problem with one of the layers of the tears or the distribution of the tears, as we said above. These conditions improve with medical management such as lid hygiene and use of artificial tears and lubricating ointments. Watery eyes caused by an abnormal lid position or a poorly functioning pump are usually easy to diagnose on physical exam. The tearing eye (true epiphora) is usually caused by poor drainage of tears though the lacrimal system. There are exceptions to this but, in the absence of other obvious problems causing reflex tearing (an inflamed eye or trichiasis, etc.) or a lacrimal pump problem (ectropion or a facial nerve palsy), epiphora means obstruction and an operation will be required to eliminate the tearing. I’ll repeat this concept because it is important: in the absence of a cause of reflex tearing or obvious lacrimal pump problem, epiphora means obstruction of the lacrimal drainage system.

Findings suggesting lacrimal system obstruction

We have already discussed the significance of epiphora. There are always exceptions but, in most patients, nasolacrimal duct (NLD) obstruction will initially occur as a unilateral problem. A history of dacryocystitis means that a NLD obstruction is present. Onset after conjunctivitis suggests that the puncta or the canaliculi have become obstructed as a result of a viral infection (one of the few bilateral onsets). Onset after facial fracture or nasal surgery implies damage to the nasolacrimal duct (Box 10-1).

Watery eyes: findings suggesting other causes of tearing

When a patient complains of watery eyes without true epiphora, ask if the symptoms are bilateral and if any ocular irritation is present. Look for findings during the examination that confirm a poor tear film or inadequate lacrimal pump (Box 10-2).

Causes of tearing by age

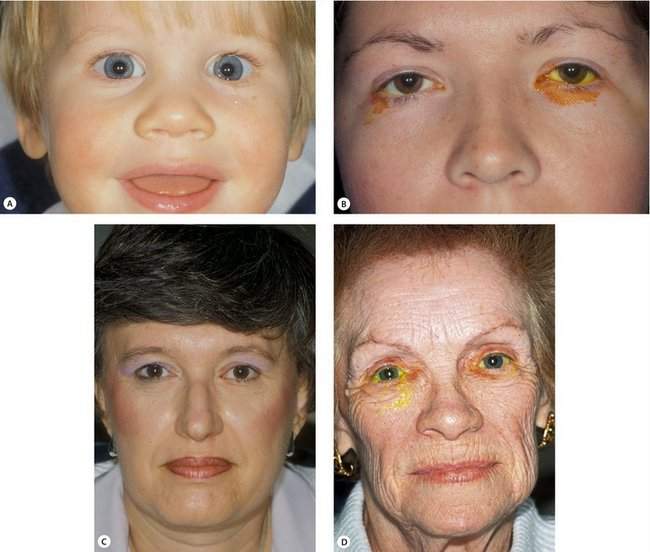

If a patient has true epiphora, you can predict the type of blockage based on the patient’s age (Figure 10-2). You will find that the following list is a great place to start for diagnosing the cause of lacrimal obstruction:

Middle-aged adults—dacryolith

A middle-aged adult, usually a woman, will describe to you recurrent symptoms of true epiphora. In some cases, the epiphora will be associated with slight pain and tenderness in the medial canthus suggesting mild dacryocystitis. In most patients, the epiphora will resolve spontaneously. Interestingly, some patients may sneeze a small cast of stones out the nose. Passing of the dacryolith usually results in resolution of the symptoms. In many patients, these symptoms will be recurrent and may require surgical treatment (Figure 10-3).

Older adults—nasolacrimal duct obstruction

An older adult, again usually a woman, will be seen with epiphora resulting from primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The cause of this scarring in the distal portion of the nasolacrimal duct is not known. Symptoms include epiphora, chronic mucopurulent discharge (chronic dacryocystitis), and acute cellulitis of the lacrimal sac (acute dacryocystitis) (Figure 10-4).

Upper and lower lacrimal drainage systems

Tear drainage can be blocked at any point from the punctum to the valve of Hasner. The lacrimal drainage system can be divided into upper and lower systems. The upper system starts at the punctum and includes the canaliculi and the common internal punctum. The lower system consists of the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct. Upper system obstruction, at the punctum or in the canaliculus, causes tearing only. Normally, mucoid secretions drain down the duct. Lower system obstruction, usually in the nasolacrimal duct, causes retention of mucus or pus in the lacrimal sac. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction may present as tearing and/or mucopurulent discharge. Partial obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct commonly occurs. Patients with partial obstruction often have tearing in the cold and wind as discussed earlier. Mucus produced in the sac is drained sufficiently to prevent signs and symptoms of dacryocystitis.

Physical examination

The patient with tearing needs a complete eye examination with an emphasis on the eyelid, eyelash, and lacrimal system (Box 10-3).

Eyelid problems

Lacrimal pump problems

Probably the most common lacrimal pump problem is related to the laxity of the eyelids associated with aging. These involutional changes do not allow tight apposition of the eyelid against the eye. Lid laxity can be diagnosed by the lid distraction test and the snap test. The normal lower eyelid cannot be pulled more than 6 mm off the eyeball. If more than 6 mm of distraction is present, the lid is said to be lax. The snap test is performed by pulling the lids downward off the eyeball. A lid with normal tone and no laxity should snap into position spontaneously. Greater amounts of laxity are associated with increasing numbers of blinks required to return the lid to normal position. I usually record the results of the snap test like this: lid returns to position with two blinks (see Chapter 3).

Punctal problems

Eversion of the lower punctum may be subtle and associated with tearing, especially in a young patient (Figure 10-5). Stenosis of the punctum often follows eyelid eversion because of the drying of the mucosa. Spontaneous stenosis or closure of the punctum is associated with echothiophate iodide (Phospholine iodide) drops, but may be associated with most antiglaucoma medications. Congenital punctal atresia is uncommon but may be present in children, often seen as a family trait. In rare patients, the canalicular system may be normal, but the puncta may be covered with a thin membrane. A discharge from a dilated punctum—the “pouting punctum”—should alert you to a diagnosis of canaliculitis, an uncommon, but frequently overlooked cause of a mattering eye.

Eyelash problems

Any condition that results in eyelashes rubbing against the eye may cause corneal or conjunctival irritation, resulting in reflex tearing. Marginal entropion is a common cause of trichiasis (see Chapter 5). Secondary lid margin changes resulting from posterior lamellar shortening may be caused by chronic blepharitis. In these patients, reflex tearing is the result of both abnormal lashes and a poor tear film.

Checkpoint

• At this point in the examination, you have eliminated eyelid or eyelash problems as a cause of tearing. What are some eyelid and eyelash problems that can cause tearing?

• You have established that the patient has true epiphora and have made a tentative diagnosis based upon the patient’s age.

• The lacrimal examination will confirm your tentative diagnosis.

The lacrimal examination

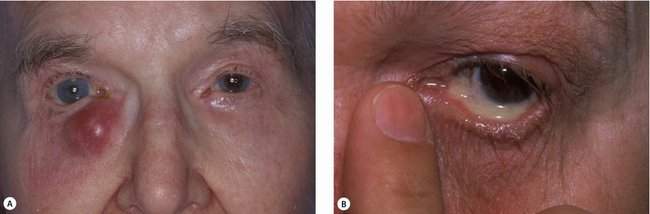

Rule out dacryocystitis first

Lacrimal system vital signs

Next check the lacrimal system vital signs (Box 10-4):

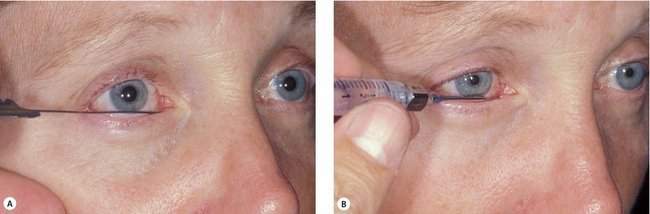

The dye disappearance test (Figure 10-6) is one of the most important lacrimal tests that you will do. After instilling a drop of topical anesthetic, place a well-formed drop of 2% fluorescein into each conjunctival fornix. After 5 minutes, check to see how much dye is retained in the eye. The yellow dye will spontaneously clear from a normal eye. The dye disappearance test is very good for confirming lacrimal obstruction. A normal result is recorded as spontaneous symmetric dye disappearance. An abnormal result is recorded as dye retained in the right or left eye. This test is most valuable when symptoms of epiphora are asymmetric. This is a very good test to use in both children and adults. In most patients, the results of the tests are obvious. However, in some older adults, the conjunctiva will stain with fluorescein in both eyes. Nevertheless, you may be able to evaluate the size of the tear film as an indicator of spontaneous tear drainage.

Figure 10-6 Dye disappearance test showing delay of fluorescein drainage and overflow of dye unilaterally.

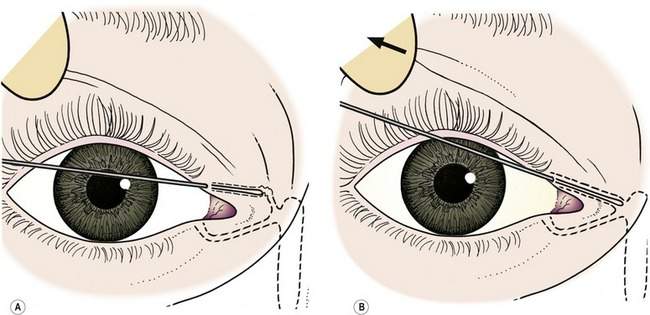

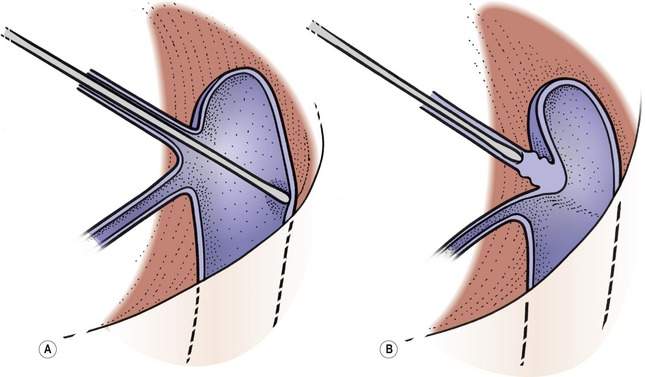

Next, demonstrate the patency of the upper and lower canaliculi using a lacrimal probe. This diagnostic test should not be confused with therapeutic nasolacrimal duct probing. To emphasize this distinction, we call this diagnostic procedure canalicular palpation (Figure 10-7, A). A 0 Bowman probe is carefully placed in the canaliculus (Figure 10-8). The lid should be pulled temporally and the probe directed toward the sac. If you meet resistance or the lid moves with the probe, you are probably pushing against the wall of the canaliculus and may cause a false passageway. The probe should pass easily to the lacrimal sac, where a hard stop should be present. This hard stop represents normal passage of the probe into the sac against the lacrimal bone. A soft stop is said to be present if a soft tissue obstruction at the lacrimal sac is encountered (Figure 10-9).

Lacrimal irrigation (Figure 10-7, B) will tell you if the NLD is normal, partially obstructed, or closed. Using a lacrimal irrigation cannula in the lower canaliculus (not the sac), you should be able to irrigate saline or water easily into the nose without any reflux around the cannula or out the upper canaliculus (normal NLD). If you can’t irrigate at all, make sure the cannula is properly placed and is not against the wall of the canaliculus. Any reflux is abnormal, suggesting resistance to flow down the duct. If the patient doesn’t taste the fluid in the throat, occlude the upper punctum with a cotton-tipped applicator (an assistant can help with this) and irrigate again. If you can irrigate into the nose with pressure on the syringe, the patient has a partially obstructed or narrow duct (functional obstruction). If you can’t irrigate with pressure on the syringe, the duct is closed (anatomic obstruction). After you are comfortable with the irrigation process, try this: when your patient has a functional obstruction, try to irrigate with progressively more pressure until you get a bit of reflux. This will give you an idea of how much fluid the NLD can drain—another form of tear drainage stress test.

Nasal examination

The last portion of the lacrimal examination includes a nasal examination. Three options for illumination and exposure are available. A hand-held illuminated speculum is a handy office tool (Welch Allyn no. 26030 illuminator and speculum or no. 26035 speculum only). Alternatively, a nonilluminated speculum may be used for exposure and a headlight can be worn to provide illumination. If you do many lacrimal operations, you may want to purchase a fiberoptic nasal endoscope, which will permit you to do the best intranasal examination. Regardless of the technique, intranasal tumors or mucosal abnormalities should be ruled out (Box 10-5).

Box 10-5 Lacrimal Examination

Checkpoint

• What are the lid distraction and lid snap tests?

• What are three signs of NLD obstruction seen on the external examination that will short cut your lacrimal system examination?

• What are the lacrimal system vital signs? (don’t skip this one)

• What is the difference between a “hard stop” and a “soft stop”?

Treatment

Treat eyelid and eyelash problems first

Ectropion, entropion, and lacrimal pump problems

In all cases, eyelid and eyelash problems should be treated before lacrimal surgery. Standard treatments for ectropion and entropion should be used. Conditions affecting the lacrimal pump should be treated. Lid deformities such as cicatricial entropion should be treated with skin grafts. Incomplete blinking can be treated with topical lubricants and gold weight placement in the upper lid. Laxity of the lower lid can be repaired using standard horizontal lid tightening procedures. Additional procedures are available for facial nerve palsy and are covered in a later chapter. In most patients, the lacrimal pump can be improved, but it is often difficult to eliminate all symptoms of tearing (Box 10-6).

After appropriate treatment of the eyelid abnormalities, the lacrimal symptoms should be re-evaluated. Before we move on to treatment of NLD obstruction, we will discuss treatment of punctal problems. Instruments and sutures of special interest in lacrimal surgery are listed in Boxes 10-16 and 10-17.

Punctal stenosis

The steps of the three-snip punctoplasty are:

1. Vertical cut of punctum: “snip 1”

2. Horizontal cut of the canaliculus: “snip 2”

3. Diagonal cut of the canaliculus: “snip 3”

In some patients, you will find that the stenosis of the punctum is associated with stenosis of the canaliculus as well. For these patients, intubation of the entire nasolacrimal system with silicone stents is appropriate. Make sure that stents will not be required before you perform a punctoplasty procedure. Once the integrity of the punctum is disturbed, stents can erode the remaining canaliculus (Box 10-7).

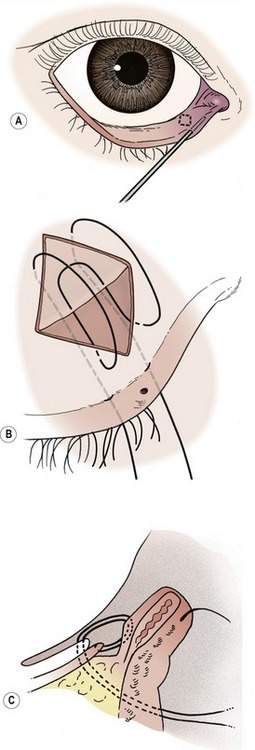

Punctal eversion

The medial spindle procedure is simple to perform and quite effective. It is a combination of a posterior lamellar shortening procedure and a mechanical inversion of the lid margin with an absorbable suture (see Chapter 3).

The medial spindle operation includes:

The steps of the medial spindle operation are:

2. Excise a diamond of conjunctiva

3. Close the conjunctiva to invert the punctum

4. Do a lateral tarsal strip operation (usually)

The chromic suture will fall out on its own in approximately 7–10 days. The overcorrection will reduce spontaneously, leaving the punctum in its normal position. Remember that the medial spindle operation must be performed before the eyelid is tightened with a lateral tarsal strip operation. Once the lateral tarsal strip sutures are tied, the medial eyelid cannot be everted to perform the medial spindle operation (Box 10-8).