Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common skin cancer, accounting for 15% to 20% of all cases of skin cancer in the United States. Similar to BCC, there is marked geographic variability in the incidence of cSCC, with more patients affected in areas with increased sun exposure. Although primary tumors can be locally invasive, it is frequently diagnosed in the early stages when it is a highly curable disease. Approximately 3,000 patients die from cSCC annually in the United States,

8 and the incidence of more aggressive or advanced tumors is increasing.

Chronic cumulative sun exposure is the prevalent risk factor for cSCC, and both UVA and UVB are implicated in tumor pathogenesis. This is significant because the sun protection factor in sunscreens only measures protection against UVB. The incidence of cSCC increases significantly with age, likely reflecting an increased cumulative exposure to sunlight. Other environmental risk factors for cSCC include a history of radiation, chronic inflammation (as in Marjolin’s ulcer), and exposure to arsenic and hydrocarbons. Chronic immunosuppression secondary to organ transplantation markedly increases the risk of cSCC up to 250 times the general population and is closely correlated to the type of transplant, immunosuppressive drug burden, and time since transplantation.

9,10 Host risk factors for cSCC include Fitzpatrick I-II skin types, fair hair, previous history of non-melanoma skin cancer, and infection with HPV. Additionally, certain inherited disorders such as xeroderma pigmentosum, epidermolysis bullosa, and albinism confer a genetic susceptibility to developing cSCC. UV-induced mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene are thought to be the molecular mechanism of malignant transformation of keratinocytes.

Diagnosis and Staging

The majority of cSCC is diagnosed on sun-exposed skin of the head and neck, dorsum of hands, lower arms, and legs. Unlike BCC, however, cSCC can arise from a premalignant actinic keratosis, identified as an area of erythematous, rough, scaly plaque that exhibits dysplastic growth and malignant potential.

Up to 80% of cSCC tumors arise in association with a preexisting actinic keratosis, although overall <1% of all actinic keratoses undergo malignant transformation annually.

11,12,13 Features of actinic keratosis that are associated with malignant transformation include inflammation, diameter >1 cm, rapid growth, ulceration, bleeding, and erythema.

14 A cutaneous horn is a clinical variant of actinic keratosis that presents as a hyperkeratotic protuberance shaped like a cone extending above the plane of the skin. Approximately 15% of cutaneous horns actually contain cSCC,

15 and excision is indicated.

cSCC in situ, also referred to as Bowen’s disease, frequently presents as a slowly growing, erythematous, scaly

patch. It is most frequently diagnosed in older patients (>60 years) and can occur anywhere on the body including the mucosal surfaces. When cSCC in situ occurs on the mucocutaneous epithelium of the glans of the penis or labia majora, it is referred to as erythroplasia of Queyrat. It occurs most often in uncircumcised men and is thought to be associated with chronic irritation, infection with HPV, and immunosuppression. It classically appears as a velvety red plaque on the glans of the penis. Progression to invasive cSCC occurs in up to 33% of cases over variable periods of time.

16 When cSCC in situ occurs in the oral or genital mucosa, it presents as adherent white patches clinically referred to as leukoplakia. Notably, this must be differentiated from other causes of leukoplakia such as chronic irritation (usually from smoking), candidal infection, and HPV infection. This often requires a biopsy of suspicious lesions. Squamous cell carcinoma develops in 10% to 20% of all patients with leukoplakia.

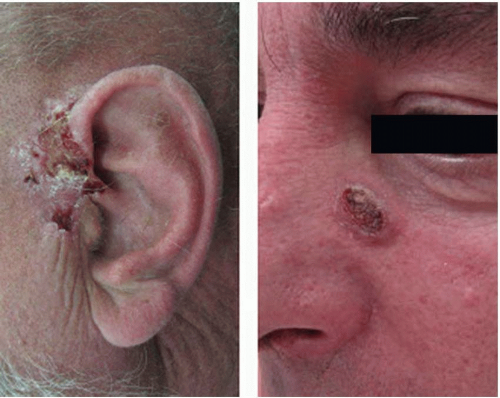

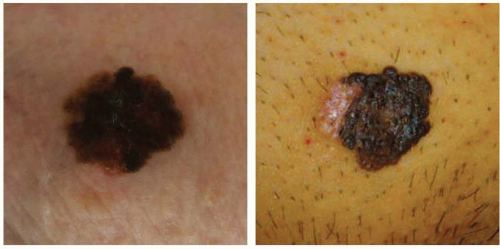

Keratoacanthoma is a rapidly growing nodule (over weeks to months) with a central ulceration or keratin plug that is found mainly in sun-exposed skin (

Figure 14.2). Left untreated, it may spontaneously involute. Keratoacanthoma is felt to be a low-grade variant of cSCC, but is clinically difficult to distinguish from high-grade invasive cSCC. Shave biopsies are not helpful in making this distinction; therefore, surgical excision is recommended.

Invasive cSCC penetrates the basement membrane to reach the dermis and either arises de novo or is associated with actinic keratosis (

Figure 14.3). Characteristic lesions are firm, raised, pink- or flesh-colored papules with frequent keratinization, scaling, ulceration, or crusting on the surface. These most often represent well-differentiated tumor types. Poorly differentiated lesions are typically soft, granulomatous nodules with areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, and ulceration and lacking in keratinization. Invasive cSCC associated with actinic keratosis in sun-exposed areas has a low metastatic risk and a favorable prognosis. De novo invasive cSCC, however, is a high-risk variant typically occurring in immunocompromised hosts or in areas of chronic irritation (such as burns) and has a metastatic rate as high as 14%.

17Diagnosis of cSCC is made by tissue biopsy to distinguish it from other neoplasms or cutaneous inflammatory conditions. In addition to definitive tumor diagnosis, patients with cSCC should undergo clinical examination of the appropriate draining lymph node basins. Palpable nodes should be biopsied by fine needle aspiration. Routine imaging studies for cSCC is not indicated, but should be obtained in patients that exhibit specific neurological symptoms or regional lymphadenopathy.

For the first time, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has introduced a completely separate staging system for cSCC, which was formerly incorporated into the “Carcinoma of the Skin” comprised of 80 different nonmelanoma skin cancers. This new TNM staging system utilizes a multidisciplinary evidence-based experience to more accurately describe the history and prognostic outcomes of cSCC (

Tables 14.2 and

14.3).

18 Due to the fact that most cSCC occurs in the head and neck, this system is meant to be consistent with the AJCC Head and Neck Staging system. The new cSCC staging system has several notable changes. The T staging (Tumor Characteristics) of the TNM system has been modified to eliminate the 5 cm size criteria and invasion of extradermal structures criteria to define a T4 lesion. Instead, a new list of “high-risk” features has been added, which impacts the overall T staging. Of these features, tumor grade now also contributes to the overall stage groups. The N component (Regional Lymph Nodes) of the TNM system has been totally revised to incorporate data indicating that overall survival decreases with increased node size and number involved.

While the majority of cSCC is diagnosed and cured in the early stages, the reported rate of regional metastasis ranges from 0.5% to 10%. While there is no consistent definition or stratification of what features of a primary tumor are considered “high risk” for regional spread, there are a number of tumor- and patient-specific characteristics that can be used to guide management. Tumor-specific features that are considered “high risk” include tumors located on the ears, lips, or within chronic wounds or scars, horizontal size >2 cm, thickness of 2 to 6 mm (low risk) or >6 mm (high risk), poorly differentiated cell types, perineural invasion, and rapidly growing or recurrent lesions.

19 Patients who are organ transplant recipients or who are diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma, epidermolysis bullosa, or HIV/AIDS are more likely to exhibit more aggressive tumor types and disease progression (

Table 14.1).

Surgical Treatment

The surgical treatment options for cSCC are similar to those of BCC and are based on assessing the risk of local regional recurrence or distant metastasis. In selected low-risk cases, destructive treatment modalities can be used with excellent results. Direct surgical excision can be used for both lowrisk and high-risk lesions. In order to increase the chance of

achieving histologically negative margins, the recommended surgical margin for low-risk lesions is 4 mm, and for high-risk lesions it is 6 to 10 mm. An increasing number of high-risk features of the primary tumor may require a larger margin of resection.

In anatomically complex areas of the face or in particularly high-risk cSCC tumors, Mohs’ micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice. Since cSCC tends to metastasize to the lymph nodes preferentially, there is some interest and initial success in using sentinel lymph node biopsy to diagnose subclinical lymph node metastasis and stage high-risk tumors. However, more controlled prospective randomized trials are required to determine whether detection of subclinical nodal metastasis will result in better clinical outcomes.

20 There is currently no role for adjuvant therapy in patients who are at risk for recurrence. Patients with distant metastasis or advanced local disease not amenable to surgery or other treatment modalities require systemic chemotherapy.