Delayed Two-Stage Tissue Expander–Implant Breast Reconstruction

F. Frank Isik

Introduction

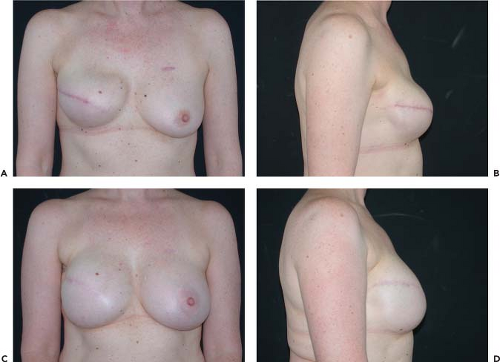

The most common method of breast reconstruction in the United States is tissue expansion followed by a saline or silicone gel breast implant. The early results with tissue expander–implant-based breast reconstructions were variable, plagued by high complication rates and poor aesthetic results (1). Over the decades, advances in expander and implant design, refined patient selection criteria, and modification in the surgical technique have improved aesthetic results and minimized complications. By adhering to the current surgical best practices, the expander–implant-based method should consistently result in an aesthetic, natural-appearing breast reconstruction (Fig. 35.1).

The expander–implant-based reconstruction method offers several advantages to women:

Outpatient surgery with relatively quick recovery

Identical skin color and texture match

Improved skin sensation

No donor-site morbidity or scars

Implant-based breast reconstruction is often presented as the simplest of all surgical options available for women who have had a mastectomy. While it is true that the operations are short outpatient surgeries, achieving an aesthetic outcome that is natural appearing, pleasing to the patient, and, in unilateral cases, matches their natural contralateral side is not simple to achieve.

The goal of expander–implant reconstruction should be a natural-appearing result, not merely symmetry in clothing. To maximize the aesthetic outcome and minimize morbidity, the plastic surgeon has to strictly adhere to guidelines regarding appropriate patient selection, expander selection, degree of expansion performed, implant selection, and timing of conversion to the final implant. Only by standardizing the approach will uniform results be achieved. In this chapter, the details of patient selection, expander–implant selection, and surgical technique will be detailed.

Indications

The primary indications for delayed two-stage expander–implant breast reconstruction are women who have had a modified radical or simple mastectomy. An alternative indication is the congenitally underdeveloped breast. Patients with Poland’s syndrome or who have sustained chest wall burns often require autogenous tissue and rarely are candidates for implant-based reconstruction alone.

The ideal candidate is a woman of near-normal weight or only modestly overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≤ 28) who has not had prior radiation, with overlying soft tissues that are mobile and nonadherent to the underlying ribs. The pectoralis muscle must be intact. The thickness of the skin flap is revealed when moving the soft tissues; they must not be of transparent thinness, in which case autogenous supplementation is indicated.

In patients with a unilateral mastectomy, the contralateral natural breast is evaluated to determine the likelihood that symmetry will be achieved. The size, base width, and degree of ptosis of the other breast will determine whether any procedures, such as a reduction, augmentation, mastopexy, or a combination augmentation-mastopexy, will be required to make the natural breast simulate the envisioned implant-based reconstruction.

Timing

Patients may present for a breast reconstruction consultation weeks before or decades after their mastectomy. Whereas immediate reconstruction is an option for many patients, there are good reasons to delay reconstruction: patients with unclear margin status and patients who smoke or have hypertension or may have complicated healing (2). Finally, patients who undergo delayed expander–implant reconstruction are more likely to achieve better aesthetics with fewer complications (3).

If delayed breast reconstruction is chosen, reconstruction should not be performed prior to 6 to 8 weeks following mastectomy. There are several reasons for this delay. First, waiting 6 to 8 weeks allows pathology issues to be completely resolved before starting reconstruction. Second, the drain has been removed and the field is sterile. Third, the viability of the mastectomy skin and/or nipple is clearly defined. Finally, waiting 6 to 8 weeks allows the breast skin to adhere to the pectoralis major muscle so that when the inferior border of the muscle is detached, the skin and pectoralis muscle act as a single fused unit, prohibiting the superior retraction of the inferior muscle border.

The patient may have had a skin-sparing or even nipple-sparing-mastectomy, but any redundant soft tissues will be smoothened during subsequent expansion (see Fig. 35.1). Of course, many patients are seen months to years after their mastectomy, and further delay is unnecessary, provided the patient does not have a chronic seroma preventing the adhesion of the skin to the muscle. In that case, complete capsulectomy is recommended as an initial procedure and allowed to heal 6 to 8 weeks prior to expander placement.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications for placement of a tissue expander include infection, nonviable chest wall skin, poor quality of the

chest wall skin, and prior radical mastectomy. Patients with tight, nonmobile chest tissues should be considered as having an absolute contraindication as they are highly unlikely to achieve adequate expansion and an acceptable aesthetic outcome.

chest wall skin, and prior radical mastectomy. Patients with tight, nonmobile chest tissues should be considered as having an absolute contraindication as they are highly unlikely to achieve adequate expansion and an acceptable aesthetic outcome.

Relative contraindications include prior chest wall radiation and obesity. Prior radiation decreases the elasticity of the skin, which resists expansion (4,5). This imposes limitations on the final reconstruction, from minor to major. The radiated chest wall skin may not relax sufficiently during expansion and, despite capsulotomy at the time of implant conversion, lead to a tight-appearing reconstruction that lacks inferior pole shape (Fig. 35.2). However, with more severe radiation changes, attempted expansion may lead to wound dehiscence and expander extrusion. Although radiated patients have to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, in general these patients are best served by autogenous methods.

Obese patients (BMI 30 to 35) are rarely candidates for the expander–implant method of breast reconstruction (6). The available expanders do not expand the thicker, heavier soft tissues well, and even the largest implants lack sufficient base width and projection. Furthermore, obese patients often have a noticeable cavitation field defect from the mastectomy, which implants cannot resolve. Obese patients are best served by weight loss and/or autogenous methods.

Preoperative Planning

Expander Selection and Markings

There are a multitude of expander designs available for breast reconstruction. The expander choices include multichamber models that allow differential upper and lower chamber fill, expanders that are designed to become the permanent implants after removing the port (Becker design), and single-chamber expanders of varying shapes and heights. The fill ports can be integrated or remotely located from the expander. Unless the surgeon is using a Becker design, remote ports can be problematic and in my view are best avoided.

Selecting the correct tissue expander is as critical as patient selection. An examination of Figure 35.3 illustrates my rationale for choosing low-height tissue expanders with integrated fill ports, such as the Inamed 133LV series. To achieve an ideal breast profile, the required soft tissue envelope expansion has to occur in the inferior one third, not in the upper portion. Examination of Figure 35.3B shows that the low-height expander expands only the lower pole of the skin envelope. When the expander is ultimately removed, the maximal inferior expansion created by a low-height expander creates a soft-tissue hammock in to which the implant is placed, so as to create a mild, yet naturally pleasing ptosis (Fig. 35.3C, D).

To determine the size of the expander to be placed in unilateral cases, the base width of the natural breast is measured with calipers. In bilateral cases, or in patients who will be

having a reduction or augmentation on their natural side, the chest wall anatomy is measured. The patient’s horizontal chest dimension is measured from the midsternum to the anterior axillary line (Fig. 35.4). This distance minus 1 to 1.5 cm is used to select the diameter of the tissue expander that will be used so as to recreate the anatomically appropriate inframammary fold curvature.

having a reduction or augmentation on their natural side, the chest wall anatomy is measured. The patient’s horizontal chest dimension is measured from the midsternum to the anterior axillary line (Fig. 35.4). This distance minus 1 to 1.5 cm is used to select the diameter of the tissue expander that will be used so as to recreate the anatomically appropriate inframammary fold curvature.

Patients are always marked in the standing position, shoulders level. The exact location of the desired inframammary fold (IMF) is outlined. A template of the expander that will be used is then drawn on the patient so that the pocket that is created is accurate for the chosen expander size and anatomically at the correct vertical and horizontal axis (Fig. 35.5). Dissection beyond the template boundaries will result in expansion in the improper location and a poor aesthetic result.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree