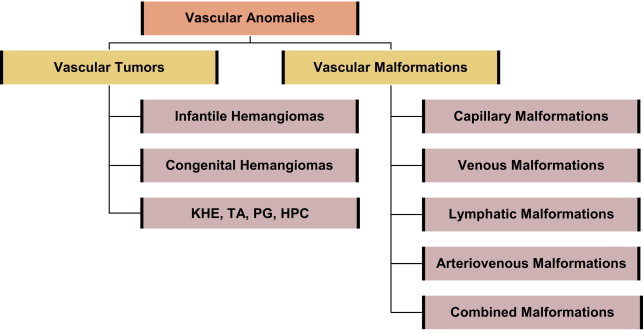

In 1982, vascular anomalies were classified as either vascular tumors or vascular malformations. Hemangiomas were identified as benign tumors that undergo a phase of active growth characterized by endothelial proliferation and hypercellularity, followed by gradual tumor regression over the first decade. Vascular malformations were described as structural congenital anomalies derived from capillaries, veins, lymphatic vessels, arteries, or a combination of these. Unlike vascular tumors, vascular malformations were shown to have normal levels of endothelial turnover and to grow proportionately with the child. This article describes the most common types of vascular anomalies and available treatment modalities.

Key points

- •

All cutaneous vascular lesions (more appropriately called vascular anomalies) can be divided into vascular tumors and vascular malformations.

- •

The most common vascular tumors are infantile hemangiomas, which present shortly after birth, grow for 6 to 9 months, and then undergo programmed cell death, leading to involution.

- •

Vascular malformations are present at birth and are composed of dysmorphic blood vessels, which grow proportionate with the size of the child and do not involute as the child gets older.

- •

Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon is associated with kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas and tufted angiomas, and not infantile hemangiomas.

- •

Infantile hemangiomas that have the potential of causing long-term functional or aesthetic issues should be treated with medicine or surgery.

- •

Management of vascular malformations is limited mostly to laser, sclerotherapy, or surgical treatment.

Vascular tumors

Infantile Hemangioma

The most commonly occurring vascular tumor is the infantile hemangioma, affecting 1 in 10 white infants in North America, although it is less common in children of African or Asian descent ( Fig. 1 ). These tumors are more common in females (3:1) and in infants with low birth weight. They are typically observed at birth or during the first several weeks of life. Lesions generally present cutaneously in the head and neck (60%), but can involve any anatomic site, including the extremities (15%), visceral organs, and brain.

Infantile hemangiomas are clinically characterized as superficial, deep, or combined, depending on their anatomic depth. Superficial lesions are typically soft, red, and raised, whereas deep lesions show a spectrum of appearance and consistency, ranging from soft and supple to raised and firmer warm masses with a bluish hue. Combined lesions have both a red epidermal coloration and a subcutaneous mass that is either blue or flesh-colored.

Although most tumors present singularly, up to 20% of affected infants have multiple cutaneous lesions. When a patient has 6 or more cutaneous hemangiomas, there is an increased risk of having visceral hemangiomas, which in turn can give rise to serious or life-threatening conditions such as hepatomegaly, gastrointestinal bleeding, profound hypothyroidism, anemia, or congestive heart failure.

Hemangiomas of infancy generally follow a predetermined clinical course of active growth (proliferation) and later tumor regression (involution); however, there is wide variation in the rate, duration, and degree of growth and spontaneous tumor regression. Proliferation begins during the first few weeks of life and generally continues for 4 to 10 months, although deep lesions may proliferate until age 2 years. The proliferative phase is followed by a period of quiescence, during which the growth rate of the lesion stabilizes. Involution occurs at 12 to 18 months and can last up to 5 to 6 years. During this time, the color of the lesion fades, becoming grayish or dull purple ( Fig. 2 ). Clinical studies show that maximum involution occurs in 50% of children by age 5 years and in 90% by age 9 years.

The cosmetic outcome after involution varies considerably and is generally unpredictable. In many patients, involution results in the restoration of normal skin. In others (20%–40%), residual changes of the skin such as laxity, discoloration, telangiectasia, fibrofatty masses, or scarring are seen in the affected area. Given this unpredictability, for patients who are not at risk, clinical monitoring, parental education, and ongoing support are preferable to early intervention.

There is sound evidence that hemangiomas of infancy are related to placental endothelial cells. Four markers of hemangioma cells that are coexpressed in placental vessels have been identified :

- 1.

GLUT1 (a glucose transporter enzyme)

- 2.

Merosin

- 3.

Lewis Y antigen

- 4.

Fcγ-RIIb

GLUT1 is strongly expressed in infantile hemangiomas, placentas, and the blood-brain barrier; however, it is not expressed in normal surrounding vascular endothelium or in vascular malformations, nor is it generally expressed in congenital hemangiomas (see later discussion). Because the positive expression of GLUT1 persists throughout all phases of the hemangioma life cycle, this histochemical marker is particularly useful in distinguishing hemangiomas of infancy from other vascular tumors and from vascular malformations.

Congenital Hemangiomas

Congenital hemangiomas are an uncommon variant of infantile hemangiomas. They differ from infantile hemangiomas in clinical behavior, appearance, and histopathology, and are occasionally diagnosed in utero. Unlike infantile hemangiomas, congenital hemangiomas present at birth as fully grown lesions and do not undergo additional postnatal growth. Congenital hemangiomas fall into distinct subgroups: rapidly involuting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs) and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (NICHs). RICHs typically involute by age 12 to 14 months, leaving a residual patch of thin skin with prominent veins and little, if any, subcutaneous fat. NICHs do not undergo involution. Both tumor types have a predilection for the head or limbs. Both tumor types generally present as solitary violaceous lesions at birth and rarely coexist in a patient with a typical infantile hemangioma. Both are high-flow lesions that can be misdiagnosed as arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). In contrast to infantile hemangiomas, congenital hemangiomas are GLUT1 negative and comprise less than 3% of all hemangiomas seen in infancy.

Problematic Head and Neck Hemangiomas

Hemangiomas can occur anywhere in the head and neck region. Hemangiomas can occur singularly on the neck, cheek, nose, ears, forehead, or scalp, or multifocally at several of these sites. The head and neck can also be the site of segmental hemangiomas that occupy an entire developmental subunit ( Fig. 3 ).

PHACES

Hemangiomas that present in developmental segments are referred to as segmental lesions. These lesions are less common than focal lesions and have a higher risk of being life-threatening or function-threatening and of having associated structural anomalies. Large cervicofacial segmental hemangiomas, particularly those on the forehead, temple, upper cheek, and around the periorbital area can be accompanied by a constellation of anomalies referred to as PHACES association. This association is more common in females. Accompanying anomalies include:

- •

Posterior fossa brain malformations (eg, Dandy-Walker malformation)

- •

Hemangiomas

- •

Arterial abnormalities

- •

Cardiac and aortic arch defects (eg, aneurysms, and congenital valvular aortic stenosis)

- •

Eye abnormalities (eg, congenital cataract, microphthalmia, and abnormal retinal vessels)

- •

Sternal clefts or supraumbilical raphes

More than 50% of patients are affected by neurologic sequelae, including seizures, stroke, developmental delay, and migraines.

Segmental hemangiomas are plaquelike in contour, typically undergo an extended proliferative period of 18 months, and unlike most hemangiomas of infancy, they do not completely regress. Furthermore, segmental hemangiomas are at a higher risk of ulceration and residual scarring. When there is an index of suspicion for PHACES association, referral should be made for an ophthalmologic and neurologic examination, screening echocardiogram, and possibly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head, neck, and chest. Patients in whom imaging reveals a central nervous system abnormality should be closely monitored. The frequency of repeated imaging depends on symptom presentation and disease progression.

Hemangiomas in a beard distribution

Sixty-five percent of patients with hemangiomas that occur in a beard distribution (ie, the chin, jawline, and preauricular areas) have associated airway involvement, and most airway hemangiomas are localized in the supraglottic or subglottic region. Patients must be closely followed and treatment should be initiated when airway involvement is suspected. Localized lesions are managed with laser ablation, intralesional steroids, surgical resection, or medical therapy (see later discussion). Tracheotomy placement is used only in refractory cases or in cases in which the airway hemangioma is extensive. Hemangiomas that occur in the beard distribution often involve the parotid glands. Parotid gland hemangiomas typically occupy the entire gland and adjacent parapharyngeal space. They grow rapidly, causing extrinsic compression of the upper pharyngeal airway. These lesions frequently have a prolonged proliferative phase (12–16 months) and may require systemic therapy if the airway is compromised. Children with extensive hemangioma of the parotid region and pharyngeal area often have chronic recurrent otitis media, likely secondary to extrinsic compression of the eustachian tube.

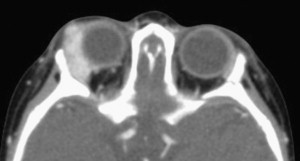

Periocular hemangiomas

Periocular hemangiomas can involve the upper lid, lower lid, or the retrobulbar space ( Fig. 4 ). Pressure from the hemangioma on the globe may lead to astigmatism and amblyopia. Early ophthalmologic evaluation and treatment are indicated for all cases of periocular hemangiomas to avoid deprivation amblyopia, which can occur with as little as 1 week of deprivation during key developmental periods. Treatment options for vision obstructing periocular hemangiomas include either medical therapy or surgical excision. Children older than 1 year who have gone untreated have rates of deprivation amblyopia as high as 75%.

Nose, lip, and ear hemangiomas

Hemangiomas involving the nose occur in close to 16% of facial hemangiomas. Proliferation of lesions on the nasal tip often distort the anatomy of the nose, causing misalignment of the nasal cartilages and mild to severe nasal volume increase. Management approaches must consider the depth, location, rate of involution, and functional and cosmetic disturbance caused by the lesion. In view of possible complications such as severe cutaneous infiltration, the consequences on nasal growth, and the psychological impact of nasal distortion, surgical excision before school age is recommended. Various surgical techniques have been reported.

Lesions of the pinna of the ear can deform normal anatomic structures and result in ulceration, with focal destruction of the auricle. Lesions obstructing the auditory canal can cause temporary conductive hearing loss. Lip lesions frequently involute slowly, sometimes leaving residual skin changes. In addition, lip ulcerations can result in feeding difficulties, secondary infection, and significant scarring.

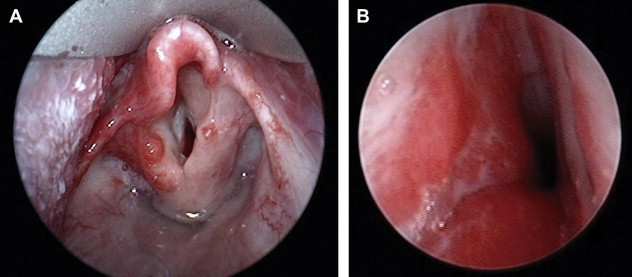

Subglottic hemangiomas

Hemangiomas can occur anywhere within the tracheobronchial tree; however, they are most commonly seen in the subglottis ( Fig. 5 ). As mentioned earlier, there is a close association of hemangiomas in a beard distribution with airway hemangiomas. However, airway hemangiomas can occur without associated cutaneous hemangiomas. Only 50% of patients with airway hemangiomas have cutaneous hemangiomas. Presentation usually occurs within the first 6 months of life, and the earlier the presentation, the greater the likelihood that patients will require surgical intervention. Symptoms typically include progressive stridor and retractions. The diagnosis is made on rigid bronchoscopy, and although radiologic evaluation (MRI with contrast enhancement) is indicated, it rarely shows extension of the lesion beyond the confines of the subglottis. Lesions are typically asymmetric and usually covered by a normal smooth mucosa. Treatment options range from medical management to laser ablation and surgical excision.

Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon

Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon is a rare, life-threatening condition associated with 2 specific subtypes of vascular tumors: tufted angioma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon is included in this section only to highlight the fact that it is not associated with infantile hemangiomas, as sometimes construed. In Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon, the tumor traps and destroys platelets. In addition to platelet trapping, there are other associated coagulopathies. As the tumor grows, it causes more platelet trapping. No single treatment approach is effective, and responses to various treatments are inconsistent.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Infantile Hemangiomas

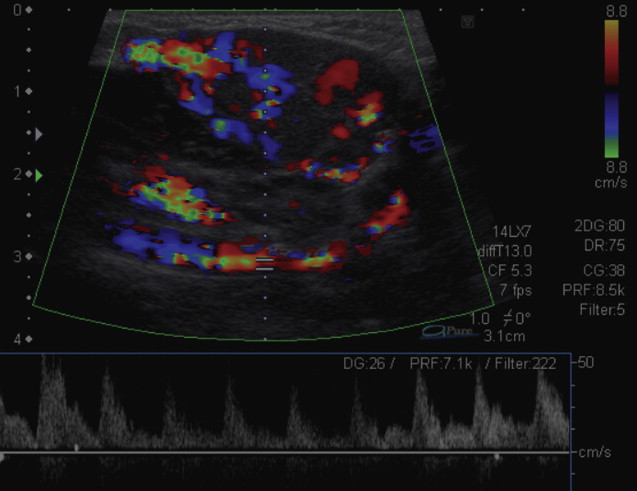

The diagnosis of infantile hemangiomas is generally established by clinical presentation, history, and physical examination. In patients with complex lesions that require surgical intervention, additional investigations can be helpful in determining the extent of involvement. Ultrasonography (US) with color flow Doppler can be useful in differentiating hemangiomas from vascular malformations that may have a similar appearance. On US, an infantile hemangioma appears hypoechoic, well-defined, and heterogeneous in texture, with small cystic and sinusoidal spaces. In most proliferating hemangiomas, a characteristic fast-flow pattern and blood vessel density (>5 blood vessels/cm 2 ) is visualized by Doppler US ( Fig. 6 ).

MRI and computed tomography (CT) scans can delineate the extent and involvement of the hemangioma and can also be helpful in distinguishing hemangiomas from other malformations ( Table 1 ). In the proliferative phase, a hemangioma appears as a well-circumscribed tumor with homogeneous parenchymatous density and intense enhancement. In the involutive phase, it appears heterogeneous, with distinct lobular architecture and large draining veins in the center and the periphery. Biopsy is indicated when the diagnosis is uncertain or when the possibility of malignancy must be ruled out.

| Anomaly Type | T1-Weighted | T2-Weighted | Contrast | Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemangioma | Soft-tissue mass, isointense or hypointense, flow voids | Lobulated soft-tissue mass, increased signal, flow voids | Uniform intense enhancement | High-flow vessels within and around soft-tissue mass |

| Venous malformation | Isointense to muscle, possible high signal thrombi | Septated soft-tissue mass, high signal, signal voids (phleboliths) | Diffuse or inhomogeneous enhancement | No high-flow vessels |

| Lymphatic malformation | Septated soft-tissue mass, low signal | Soft tissue mass, high signal, fluid levels | Rim enhancement or no enhancement | No high-flow vessels |

| Arteriovenous malformation | Soft tissue thickening, flow voids | Variable increased flow voids | Diffuse enhancement | High-flow vessels throughout abnormal tissue |

Treatment of Infantile Hemangiomas

Most uncomplicated focal hemangiomas involute spontaneously and do not require intervention. Nevertheless, rapidly proliferating lesions are sometimes problematic and can cause a wide array of complications, including ulceration, infection, hemorrhage, necrosis, airway obstruction, loss of vision, and cardiac failure. To ensure timely intervention should any of these complications occur, patients should be closely monitored during the proliferative phase. Optimally, management strategies for complex lesions should be planned by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians with expertise in treating vascular anomalies. Management decisions should consider the size and location of the lesion, the presence of complications at diagnosis, the age of the patient, and the rate of tumor growth. Large segmental hemangiomas and life-threatening or function-threatening hemangiomas are likely to require immediate treatment. Immediate treatment is also essential in the presence of ulceration or secondary infection. Serious aesthetic concerns such as the possibility of permanent disfigurement or scarring warrant early intervention.

These patients almost always require multimodal therapy. Major therapies include pharmacotherapy, chemotherapy, laser therapy, and surgical excision. Recently, the dramatic effect of oral propranolol has been reported in several small case series, and prospective studies are under way at several major centers. Although research regarding propranolol is in its infancy, this medication has replaced steroids as the first line in medical management. Propranolol is discussed further later.

Ulceration is the most common complication of hemangiomas, often occurring in lesions involving the nose, lips, and periorbital region. Most ulcers develop during a phase of rapid growth. They are often painful and can lead to infection, anemia, scarring, and disfigurement. Treatment should focus on decreasing pain, preventing secondary infections, and promoting reepithelialization. Painful ulcerations may require oral medications such as acetaminophen or acetaminophen with codeine. Superficial ulcerations generally respond to supportive therapy such as gentle cleansing and the daily application of a topical antibiotic. Dressings that cover the ulceration such as DuoDERM (Convatec, Skillman, New Jersey) or Mepilex (Molnlycke Health Care US, LLC, Norcross, Georgia) can provide pain relief and promote healing. When an associated cellulitis occurs, oral systemic antibiotics are given. Ulcerations on localized cervicofacial lesions are amenable to surgical resection, which generally results in excellent cosmetic outcomes. When resection is not feasible or desirable, Pulse Dye Laser (PDL) is used to promote reepithelialization and decrease pain. This approach is particularly helpful in anatomic areas that are not amenable to resection, such as extensive facial lesions. Products such as imiquimod, which stimulates endogenous interferon production, and becaplermin gel, which seems to accelerate reepithelialization, have been used for treating refractory ulcerated hemangiomas, but require further study.

Until recently, corticosteroids have remained the first line of therapy for the treatment of complicated hemangiomas. Currently, the 2 indications for the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of infantile hemangiomas is for those patients who fail propranolol treatment or for intralesional injection in small focal hemangiomas. Local injection is especially effective in the periorbital region, nasal tip, and subglottic region. Some surgeons and ophthalmologists recommend using general anesthesia, whereas others perform the procedure on an outpatient basis using a topical anesthetic. A long-acting steroid (eg, triamcinolone acetonide) and a short-acting steroid (eg, betamethasone acetate) can be combined in a total volume that generally does not exceed 2.5 mL. The dose and volume are individualized according to the size of the lesion. A 25-gauge needle is used and injections are made directly into the hemangioma in different directions through the same needle hole. After this stage, direct pressure is applied for 2 to 10 minutes to stop bleeding. In subglottic lesions, it is important to avoid direct injection of the cricoid plate, because cartilage resorption may occur. Although this approach is associated with a 70% to 90% response rate in periorbital hemangiomas, a known complication is the risk of retinal artery embolization and thrombosis, with resulting blindness. To lessen this risk, fundoscopic retinal examination should be performed as the lesion is slowly injected so as to recognize early signs of retinal arterial flow interruption. Adrenal suppression and failure to thrive have also been reported after local injection for periocular hemangioma.

Propranolol, a nonselective β-blocker, has recently been introduced as a novel modality for the treatment of proliferating hemangiomas. The dramatic effect of propranolol therapy on hemangiomas was first described in 2008 by Leaute-Labreze and colleagues. These investigators serendipitously discovered that propranolol induced early regression of infantile hemangiomas during their proliferative phase. Their reported findings in a small series of infants sparked the enthusiasm of clinicians eager to identify appropriate uses for propranolol. Buckmiller and colleagues reported the successful management of tracheal hemangiomas in a young patient with otherwise treatment-resistant airway lesions. Within 6 weeks of beginning oral propranolol (2 mg/kg/d), airway compromise was eliminated and the patient had complete resolution of endoscopically visible disease. No side effects occurred. Denoyelle and colleagues reported the successful management of 2 infants with subglottic hemangiomas that were resistant to established medical treatments. Both patients’ subglottic hemangiomas responded dramatically to propranolol and no side effects were noted. The mechanisms of action are speculative, but may involve the downregulation of angiogenic factors and upregulation of apoptosis. Early research shows that propranolol may be a safe and effective therapeutic strategy for both cutaneous and airway lesions. There is controversy as to the diagnostic testing needed before drug administration and the appropriate venue (inpatient or outpatient) for the drug. Box 1 shows an inpatient and outpatient algorithm developed by our vascular anomalies team. In general, we advocate inpatient protocol for infants younger than 2 years and children with comorbidities. The parents of all other children are given the choice of inpatient or outpatient treatment. Side effects that have been reported to date include hypoglycemic seizures and sleep disturbance.

Inpatient Propranolol Algorithm

- •

Preadmission diagnostic testing: echocardiogram to rule out congenital anomalies in patients with a history of murmurs, failure to thrive, or other significant medical comorbidities; electrocardiography (EKG) to rule out cardiac arrhythmia

- •

Admit to telemetry unit with continuous heart rate and blood pressure monitoring

- •

Initiate propranolol at 0.5 mg/kg by mouth twice a day for 2 doses; increase to 1 mg/kg by mouth twice a day for 2 doses; increase to 2 mg/kg by mouth twice a day

- •

Propranolol is increased in this manner if the patient shows no adverse response to the administration of the medication

- •

Check blood glucose 2 hours after each dose of propranolol

- •

Check EKG 24 hours after initiation of propranolol

- •

Discharge home after second dose of propranolol at 2 mg/kg, with contact information if questions or problems arise

- •

Parents are instructed to maintain a strict feeding regimen. If the child is younger than 6 months, feeds should be every 2 to 4 hours. Older children can be spaced to feeds every 6 to 8 hours

- •

Parents are instructed to hold medication if the child becomes ill or has decreased oral intake

Outpatient Propranolol Algorithm

- •

Diagnostic testing: same as for inpatient algorithm

- •

Monitor on telemetry unit for 6 hours with continuous blood pressure and heart rate monitoring

- •

Initiate propranolol at 0.5 mg/kg

- •

Check blood glucose 2 hours after each dose of propranolol

- •

Discharge instructions as for inpatient algorithm, with contact information if questions or problems arise

- •

Continue propranolol at 0.5 mg/kg by mouth twice a day or 1 week

- •

Return to hospital for 6-hour admission on telemetry unit, during which propranolol is increased to 1 mg/kg. An EKG is obtained before increasing the dose, and blood glucose is checked 2 hours after dose. Discharge home at this dose for a week, with discharge instructions as previously

- •

Return to hospital for 6-hour admission, during which propranolol is increased to 2 mg/kg. Blood glucose is again checked 2 hours after dose. Patient is discharged home, with discharge instructions as previously with follow-up in 4 weeks

Lasers have a limited role in the treatment of hemangiomas. The PDL is often used at the end of the involution phase to reduce any residual vascular markings. PDLs are also used as mentioned earlier to promote wound healing, reepithelialization, and pain control for ulcerated hemangiomas that are refractory to medical management. CO 2 and ND:YAG (neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) lasers have been used to ablate airway hemangiomas, although overaggressive use of these lasers can cause scar deposition and subglottic stenosis.

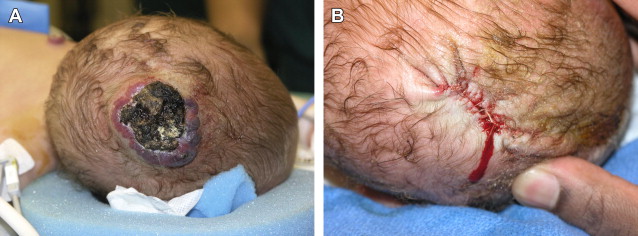

The indications for the surgical excision of hemangiomas are in evolution, especially given the natural regression of these lesions and the efficacy of medical management. Nonetheless, there are several clinical situations in which surgical excision is an attractive treatment option ( Box 2 ). Large hemangiomas that are likely to leave large amounts of fibrofatty residuum or excess skin are often good candidates for surgical excision. Ulcerative hemangiomas that fail medical management and can be excised completely are another candidate for surgical excision ( Fig. 7 ). Periorbital hemangiomas and airway hemangiomas that are causing significant signs and symptoms and are unlikely to respond quickly or do not respond to medical management are often best treated by surgical excision. Hemangiomas that are not completely resolved by school age and cause psychosocial distress can also be treated with surgical excision. The timing of surgery remains a controversial subject, particularly in regard to early surgery on hemangiomas that are disfiguring and in which the results of spontaneous involution are difficult to predict. Surgical intervention should be considered when surgery is believed to provide a better overall outcome to the patient than natural regression or medical management.

- •

Noninvoluting congenital hemangioma.

- •

Ulcerative hemangioma that will likely leave a large scar.

- •

A hemangioma that is causing significant functional compromise or signs and symptoms and is not responding expeditiously to medical management. Examples of functional compromise include obstruction of visual axis with changes in vision, or airway obstruction.

- •

A hemangioma that has a pedunculated appearance, and therefore will likely not involute completely.

- •

A hemangioma that causes significant psychosocial or appearance issues to the patient as they enter school and that can be removed with a satisfactory cosmetic outcome.