Chapter 63 Cost-containment and outcome measures

![]() IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER ![]() PowerPoint Presentation Online

PowerPoint Presentation Online

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Socioeconomic impact of burns

Burn injuries continue to plague the economic systems of both developed and underdeveloped countries. In developed countries, severe disabilities secondary to burns produce significant financial losses; in the developing world, loss of life from burns is extremely high. The death toll is highest at the extremes of age; young adults more frequently survive with disabilities that truncate their production in society.1 Minor burns represent economic loss in the form of sick leaves, and their sequelae sometimes interfere with the productivity of the victim. Survivors of massive burns are more prone to develop long-term sequelae, and consequences to their families and to society can be devastating.2,3

The overall incidence of burns in developed countries is still relatively high, while the numbers of persons who die from burns is remarkably low. It is reported that 820/100 000 persons per year are burned, with 30/100 000 persons per year requiring specialized treatment. Admissions to burn centers account for 6.5/100 000 persons per year. The gross burn mortality in developed countries (people who die at the scene of the accident plus people who die in specialized units) is only 0.6/100 000 persons per year. LD50 (the body surface area burned that kills 50% of people) in the pediatric population4,5 and in young adults6 is over 90% total body surface area (TBSA) full-thickness burns, and over 40% TBSA full-thickness burns in the elderly.6 Burn mortality indices under 4% are common among inpatient populations.

The social cost of minor burns in developed countries is significant. In Western Europe, these costs, including the loss of production at work of the individual, social security cost, and the cost of the entire treatment is around 7000 Euros. For severe burns, social costs are much higher and are to be estimated over 40 000 Euros per patient.7 These are underestimates because the true social costs of long-term disabilities resulting from burn injuries are not yet well determined.

The world estimate is more dismal. World statistics put burn injuries to the level of a major health problem. Burns described as ‘minor’ in developed countries produce severe disabilities or even death in developing countries. There are more than 150 000 fire deaths every year in the world, and approximately 30 000 000 people in the world require admission to specialized units. In developing countries, survival of patients with burns over 40% TBSA burned is minimal.8

Outcome measures

For a long time, burn mortality has been considered a major outcome measure of the quality of burn care. Improvements in burn mortality, though, have produced a change in the expectations of burn care providers.5,9 No longer is survival per se a sufficient outcome measure (mortality is being questioned as a true outcome measure in current burn practice10), but psychosocial adaptation and physical rehabilitation are of prime importance. The need for some supportive services, therefore, may extend throughout the patient’s lifetime.

Burn mortality

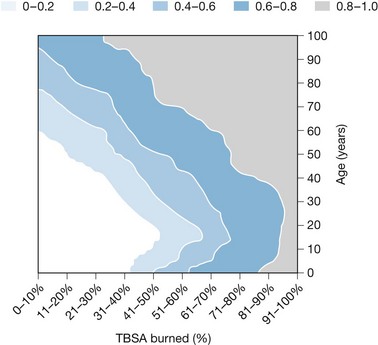

Survival is still one of the major outcome measures in burn centers. It is the most frequently used measure because data is easily retrieved and easy to compare among different centers. Although every burn center has its own particular limitations, it is clear that there exists a minimum standard of burn survival (i.e. LD50 of 90% TBSA burned in children and young adults) that should be met given the social and economic situations are provided. In order to achieve the minimal standards of care, it is important to analyze the comparability of results of every burn center. Local geographic and social parameters vary, thus the generation of models of probability of death or probit analysis11,12 with statistical logistic regression13 has proven useful for surveying the outcome of burn victims (Fig. 63.1). It has the benefit of comparability,11 but it presents also the benefit of internal control of the burn center, since the logistic model represents the standard of care for that given center. Ideally, the probability of survival should increase with time, reflecting the continuous improvement of the quality of care. The responsibility of the burn team is to continuously improve those results and generate new revised models of probit analysis. The advantage of this analysis is that it includes all the particular social and economic situations of the local geographic area, and on the other hand it is comparable with the results of other centers. One of the main disadvantages is that the prediction is based only on age and TBSA burned.

Other indexes, such as the abbreviated burn severity index (ABSI),14 includes the patient’s sex, depth of the injury, and inhalation injury as risk factors that determine the severity of the burn, achieving a more accurate predictive factor. If additional factors are considered, such as pre-existing disease or the abuse of toxic substances, the specificity and sensitivity of the predictors improve.15 However, even though survival after burn trauma is one of the primary objectives of burn centers, raw mortality and relative mortality (mortality index corrected per age and sex groups in the general population) are no longer the only outcome measures in burn health systems.10

Length of stay (LOS)

Length of stay (number of days admitted to hospital) is a relevant indicator for hospital administrators. It is a direct indicator of cost of treatment and its relevance applies to all patients, regardless their final outcome. As pointed out by Pereira et al.10 data on burn survival have been available for decades, but less information has been published on LOS. Length of stay is an indirect indicator of morbidity (uncomplicated patients should leave hospital sooner than complicated patients), although it must be interpreted with caution. Patients may stay longer for rehabilitation despite being healed completely, or, conversely, patients may be discharged home and readmitted soon after as rehabilitation patients to change insurance coding and reimbursement. The best way to standardize LOS to allow easy access and comparison is to express it as a function of burn size (days/%TBSA). It can be then used as an efficiency indicator of burn care provided, with the ratio below 1 (<1 day per 1% burn) as a goal for burn treatment. However, it works very efficiently and as a good comparison method for massive burns, but it can produce important bias when considering small burns with specific locations (hands, face, genitalia, feet); depths (deep burns requiring flaps), or age (pediatric or geriatric population). We have to assume that certain populations will stay longer than the ‘ideal’ ratio and administrators and insurance companies should be aware of that.

Quality of life

The grade of disability and the quality of life achieved by burn survivors are also considered main outcome measures. In modern society, it is not only survival that is important, but also the quality of life achieved. Survival at any price may lead to subtotal or total disability, which may or may be not acceptable for all persons. The latest reports of psychosocial adaptation of patients surviving severe or massive injuries show an optimal response and adaptation in society.2,3 Moreover, most burn survivors achieve social adjustment that is within normal limits. Physical disabilities are certainly common and so is change in body image acceptance. Location of the injury (hands, face, etc.) and background personality and premorbid psychological status are also extremely relevant for coping with the new situation (Box 63.1).

Box 63.1 Categories of burn impairment and disabilities

Class I: Impairment of 0–10%. No limitation or minimal limitation in the performance of the activity of daily living. Exposure to certain physical and chemical agents might increase limitation temporarily. Skin disorders are present, but no treatment is necessary

Class II: Impairment of 10–25%. There is limitation in the performance of some of the activities of daily living. Skin disorders are present and intermittent skin treatment is required

Class III: Impairment of 25–50%. There is limitation in performance of many of the activities of daily living. Skin disorders are present, and continuous treatment is required

Class IV: Impairment of 55–80%. There is limitation in performance of many of the activities of daily living. Skin disorders are present, and continuous treatment is required, which include periodic confinement to home or healthcare institution

The physical examination of a burn victim is much the same as the disability evaluation for any patient. With history and physical examination, and using the tables of the American Medical Association’s Guide to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, a rating of impairment can be made.16 The techniques of measuring, although complex and time-consuming, are practical and scientifically sound. A combined approach, with an occupational or physical therapist who makes the objective determination of physical impairment and a burn surgeon who makes the subjective determinations, is advisable, and, once thorough assessment has been performed, the patient will be placed in one of the categories for permanent impairment and disability (Box 63.1). Impairment and disability assessments are most relevant for insurance companies, social security, worker’s compensation, and the legal system. Since the burn team is not only responsible for the acute care, but also for continuous quality improvement and the evaluation of outcome characteristics, disability determination is an integral part of modern burn care. Only with such evaluation can the quality of outcomes be improved.

Although disability and impairment assessment is one of the main outcome measures, it alone does not describe the quality of life that patients achieve after burns are healed and all formal treatment is finished. One of the measures that adapts to healthcare systems is the Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY) introduced by Torrance in 1986.17 One QALY is a measure of all benefits of health treatment that include increase in life expectancy and enhanced quality of life. The increase in life expectancy is measured in number of years, while quality of life is measured in a scale with a maximum of 1 (perfect health). In this scale, 0 corresponds to death. There are negative numbers, since there are health situations that are considered by patients to be worse than death. The QALY are, therefore, the number of years with perfect health which are also compared to the number of years lived in a specified state of health. For example, if a person lived for 70 years in perfect health and died, they would accomplish 70 QALY. Conversely, if a person lived 45 years in perfect health, and then acquired chronic renal failure, with a quality of life of 0.4 and died at age 70, they would accomplish 55 QALY [45 QALY + 25(0.4)]. There are two sorts of methods to calculate QALY, the ‘standard gamble’18 and the ‘time trade-off’.19 The second method is the simplest and the most used. Patients are confronted with two situations: the situation of disease and/or sequelae for t years and the situation of perfect health for x years followed by death. The utility of any treatment of a chronic condition is represented by x/t. Life expectancy under a certain chronic condition is compiled from medical literature. This time is converted to QALY under perfect health, and the risks of the medical treatment are then evaluated in terms of the effectiveness in producing QALY.

When QALY are applied to burn patients, it is easy to assume that the treatment of severe injuries, which will result in death without treatment, will produce an important number of QALY. Nevertheless, many burn injuries heal with sequelae, so that the quality of life achieved is not that of perfect health, but sometimes quite less than that. Patients that survive life-threatening injuries acquire a high number of years in terms of life expectancy, whereas the total number of QALY is often less than the optimal number. This is confusing since the overall assessment of quality of life that burn patients express in the long run is usually higher than expected.2,3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree