Cosmetic Issues of Concern for Potential Surgical Patients

Chang-Keun Oh

H. Ray Jalian

Stephanie R. Young

Seong-Jin Kim

Darker-skinned individuals (Fitzpatrick skin type IV through VI) represent 30% of the population, U.S. population and the majority of the global population (see Chapter 2), thus physicians are more likely to encounter such patients in their clinics and practices, and therefore must know how to treat diverse skin types. Until recently, training programs have paid little attention to ethnic skin, focusing instead on procedures and treatments relating to fair-skinned individuals. Today’s rapidly increasing population of darker skin types requires that cosmetic surgeons recognize the need for safe, effective treatments for people of color.

Several studies have assessed the incidence of skin diseases in patients of color. Halder et al.1 assessed the incidence of common dermatoses in 2,000 patients in a predominantly black dermatologic practice. The four most common skin diseases, in order of incidence, were acne vulgaris (27.7% of patients), eczema (23.3.%), pigmentary disorders other than vitiligo (9%), and alopecias (5.3%). Alopecias were predominantly chemical and traction alopecia. Pigmentary disorders were predominantly postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and melasma.

Table 6-1 Cosmetic issues of concern for darker ethnic groups | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Child et al.,2 assessing the spectrum of skin disease in a predominantly black population in southeast London, recorded diagnoses in 461 consecutive African, Afro-Caribbean, and mixed-race patients. The most common diagnoses in the 274 adults included in the study were acne vulgaris (13.7%), eczema (9%), psoriasis (4.8%), and keloidal scars (4.1%). Several of the aforementioned conditions are considered “cosmetic.”

The cosmetic surgeon should have an in-depth understanding of the physiological and functional differences that exist between fair-skinned individuals and their dark-skinned counterparts. Data, however, relating to these primary differences remain limited.3,4,5 Despite this, surgeons who keep diversity of skin in mind in their practices will do a great benefit to their patients by allowing their postoperative experience to be predictable and without complications.

This chapter will provide an introductory overview for cosmetic issues of concern in darker racial ethnic groups. These issues include pigmentation disorders, skin laxity, wrinkles, sensitivity, oily skin and acne, and scarring.6 Many of these disorders will be discussed in depth in other chapters (Table 6-1).

Pigmentary Disorders

Variation of skin color is believed to have evolved as a result of selective pressures present in particular environments, mainly extremes in light and temperature. The most apparent and important morphological difference in darker racial groups involves pigmentation. The reactivity of melanocytes and the profound tendency toward hyperpigmentation are unique characteristics of darker-skinned individuals.

It is well established that there are no racial differences in the number of melanocytes7 in darker compared with lighter skin types. Differences in melanocytes and melanin production have been discussed in Chapter 2. The increased epidermal melanin content of darker-skinned individuals provides greater intrinsic photoprotection, perhaps explaining why problems such as photodamage, actinic keratoses, rhytides, and skin malignancies are less common in deeply pigmented skin. However, the increase in epidermal melanin and the often capricious response of melanocytes to inflammation or injury can lead to distressing dyschromias characterized by hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation.

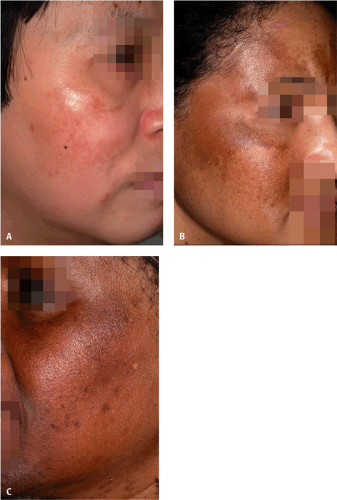

Melasma is a troublesome acquired hypermelanosis, usually occurring symmetrically on the face (Fig. 6-1). Although melasma can affect all people, Asian, Hispanic, and black women are most commonly affected.8 Although the precise cause of melasma is unknown, multiple factors have been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of this condition. These include genetic influences, sunlight

exposure, pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, cosmetics, and medications, such as phototoxic and antiseizure medications. Recently, Grimes et al. reported hyperactive melanocytes and increased epidermal melanin in the affected skin of patients with melasma.9 Electron microscopy studies showed enlarged melanocytes with increased numbers of melanosomes and prominent dendrites. This study suggested that melasma may be a consequence of hyperactive and hyperfunctional melanocytes causing excessive melanin deposition in the epidermis and dermis.

exposure, pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, cosmetics, and medications, such as phototoxic and antiseizure medications. Recently, Grimes et al. reported hyperactive melanocytes and increased epidermal melanin in the affected skin of patients with melasma.9 Electron microscopy studies showed enlarged melanocytes with increased numbers of melanosomes and prominent dendrites. This study suggested that melasma may be a consequence of hyperactive and hyperfunctional melanocytes causing excessive melanin deposition in the epidermis and dermis.

Figure 6-2 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Note hyperpigmented macules and patches of the face. (Courtesy of Pearl E. Grimes, MD.) |

Another important cosmetic pigmentation issue is PIH (Fig. 6-2). PIH is characterized by an acquired increase in cutaneous pigmentation secondary to an inflammatory process. Excess pigment deposition may occur in the epidermis or in both epidermis and dermis. The condition occurs in all racial and ethnic groups; however, it has a higher incidence in people with darker complexions. Previous studies have suggested that inflammatory reactions that cause a release of arachidonic acid from cell membranes may be a cause of PIH. Mediators implicated in PIH include endothelin 1, prostaglandins, interleukin-1, and stem cell factor.10,11

Lentigines

Solar lentigo (Fig. 6-3) are common light brown to brown lesions occurring as discrete hyperpigmented macules on

sun-exposed areas of skin, such as the face, arms, chest, and back. Solar lentigo is induced by natural or artificial ultraviolet light sources. Such lesions are common in skin type IV, in particular in Asians and Hispanics. They are less common in blacks. Histologically, they are characterized by elongated rete ridges, club-shaped extensions, and a proliferation of melanocytes, and keratinocytes.12

sun-exposed areas of skin, such as the face, arms, chest, and back. Solar lentigo is induced by natural or artificial ultraviolet light sources. Such lesions are common in skin type IV, in particular in Asians and Hispanics. They are less common in blacks. Histologically, they are characterized by elongated rete ridges, club-shaped extensions, and a proliferation of melanocytes, and keratinocytes.12

Hori’s nevi are acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules symmetrically located on the forehead, temples, eyelids, and malar regions. These often occur in young women with a family history for these lesions. They are also aggravated by sun exposure.13 Histologically, the overlying epidermis is normal. In the papillary and upper reticular dermis, dendritic melanocytes are present and surrounded by a fibrous sheath.14

Treatment with laser light can create unwanted epidermal side effects, such as blistering, dyspigmentation, and scarring, because the higher epidermal melanin content acts as an additional chromophore (Figs. 6-4 and 6-5). A higher level of laser expertise and clinical experience in treating darker skin is mandatory to ensure that patients are treated safely and effectively. Test spots should always be performed as an aid to selecting the safest and most effective parameters of treatment, including determining the appropriate fluence, wavelength, and thermal relaxation time. Efficient cooling devices are essential to prevent the unwanted thermal damage that could potentially cause pigmentary complications. Transient hyperpigmentation can be prevented or relieved by the pre- and postoperative use of hypopigmenting agents.

Vitiligo is a relatively common pigmentary disorder characterized by patches of depigmentation. The disease affects 1% to 2% of the population and shows no racial or ethnic predilection. Vitiligo is indeed a disfiguring and psychologically devastating disease. The disorder may be imperceptible in individuals with skin types I and II. However, the condition is striking in darker racial ethnic groups (Fig. 6-6). Patients with vitiligo experience profound psychological trauma in light of the cosmetic deformity. Psychological profiles document perceived job discrimination, low self-esteem, suicidal ideations, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships.15,16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree