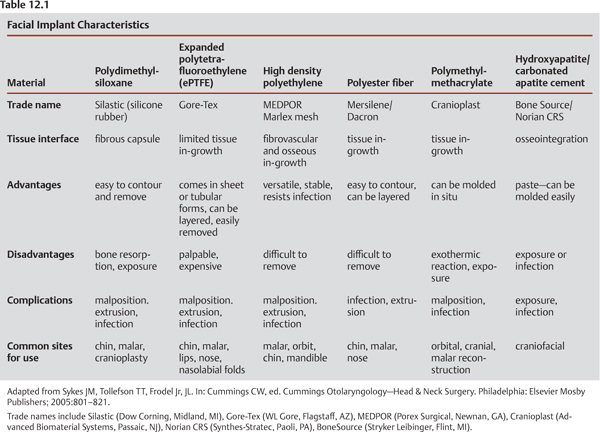

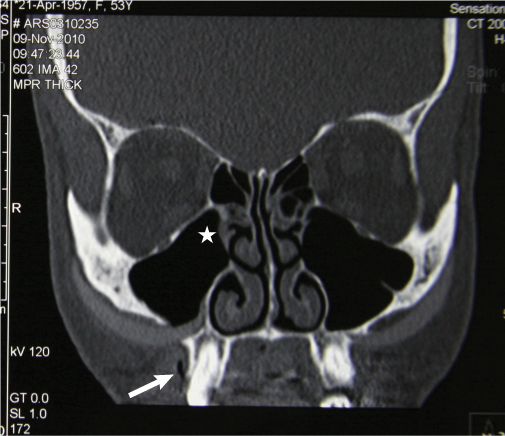

12 Contemporary care in facial plastic surgery mandates familiarity and facility with facial implants. Over the past few decades, trends have stressed the restoration of facial volume and the importance of enhancing skeletal facial proportions. One has only to look at the success of facial fillers to see this. Like injectable fillers, facial implantation has also become an increasingly popular way to replenish lost volume and to correct contour abnormalities that result from developmental, traumatic or age-related etiologies. When it is possible, most surgeons prefer the implantation of autologous tissue; however, the additional morbidity associated with the harvest of donor tissue, the limitation of tissue availability, and the risk of graft distortion or resorption are potential drawbacks. Alternatives to autologous tissue include allografts, xenografts, and alloplastic materials. The use of allograft tissue tends to have similar limitations to the use of autologous tissue in terms of resorption and distortion (perhaps more so), in addition to the remote possibility of disease transmission. Their more predictable long-term outcomes and limitless availability make alloplastic implants particularly attractive; however, the use of alloplastic implants is not without its own set of risks (including elevated risk of infection), and the search for the optimal implant material continues.1 Table 12.1 outlines the commonly used facial implant materials and their characteristics. Most alloplastic implants used today for facial enhancement are synthetic polymers. These are macromolecules of repeating monomeric units. They may be solid polymers, such as polydimethylsiloxane or solid silicone (Silastic, Dow Corning, Midland, MI) and polymethylmethacrylate; porous polymers, such as high density porous polyethylene (MEDPOR, Porex Surgical, Newman, GA) and fibrillated expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) (Gore-Tex, WL Gore, Flagstaff, AZ); or meshed polymers such as polyethylene terephthalate (Mersilene, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). In addition, certain metals such as gold (Au-79) and titanium (Ti-22) are used as implants, primarily for reconstructive purposes.2 Ceramics such as hydroxyapatite are also useful, particularly in craniofacial reconstructive procedures. The biocompatibility or interaction between implant and host is influenced by many factors, including the chemical composition of the implant material, host reaction, and surgical technique. The ideal implant material is nontoxic, nonantigenic, noncarcinogenic, acceptable to the host, durable, and resistant to infection. It is costeffective, easy to sculpt or customize without compromising its integrity, easy to insert, and able to withstand mechanical strain without changing its shape. It has few surface imperfections, is able to conform to irregular surfaces, and is easily removable without causing significant tissue injury.3 Although a multitude of implant materials are available in the market, currently none satisfy all these criteria. Each implant material has its own risks and benefits, and there is presently no ideal permanent implant. Understanding the complications associated with facial implantation from study of the literature has its limitations. Some surgeons are reluctant to report complications or poor results, and patients with adverse outcomes often seek alternative opinions and are lost to follow-up.4 In any event, complications from facial implantation do occur and result from a combination of factors related to the patient (host), the implant material, and the surgeon’s technique. The following discussion will treat each of these areas separately. Patient-related complications are typically from mismanaged expectations that lead the patient to be dissatisfied with the outcome. These complications are largely preventable with open and frank communication between patient and surgeon. Prevention begins with a comprehensive evaluation of the patient, including careful analysis of standardized digital photographs. Consistent photographic techniques with appropriate views are essential for accurate preoperative and postoperative comparisons. Inadequate preoperative analysis can lead to selection of the improper implant and an unhappy patient. Computerized morphing techniques may be used to manage patient expectations and demonstrate the need for appropriate additional interventions to achieve the best possible aesthetic outcome. One must be careful to emphasize that such morphing is an approximation and by no means a guarantee of a surgical result. Having the patient sign a waiver to this effect is helpful from a legal standpoint.5 Although they are designed to be inert, specific implant materials can cause hypersensitivity reactions in some patients and therefore produce adverse outcomes. Hypersensitivity tends to be more common with filler materials such as bovine collagen, which has a 2–3% incidence of an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction and requires double skin testing prior to usage. Complications from surgical technique are somewhat generic to any implantation procedure, but the risk varies with specific sites and the implant material(s) used. Most surgical complications are fortunately minor and self limiting. Major complications must be dealt with expeditiously to avoid long-term sequelae. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy and meticulous attention to surgical technique are critical to avoid adverse surgical outcomes. The surgical complications commonly encountered with facial implants are discussed below. Blood that accumulates in a tight pocket can lead to pressure necrosis of the overlying skin and soft tissue, resulting in implant exposure and extrusion. Hematomata need to be drained and the bleeding controlled in a timely fashion.6 Depending on the site of implantation, nerve injury can manifest as paresthesias or dysesthesias involving the infraorbital or mental nerve. Occasionally, weakness involving the frontotemporal or marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve (VII) can also occur. Nerve injuries are commonly neurapraxias resulting from aggressive retraction or transmitted thermal injury, and they typically resolve in less than three weeks. Should they persist beyond that time period, one must have a low threshold for exploring the area and ruling out malposition of the implant and induced neurapraxia.7 Very rarely, nerve injuries can be permanent.6 Postoperative facial edema after implantation typically resolves in three weeks or less. Occasionally edema can last several months and can be caused by chronic inflammation. Discrete areas may be treated with intralesional triamcinolone.6 Patients commonly need reassurance. Displacement of the implant from its intended position is a well-known complication of facial implant surgery. Malposition itself is problematic (e.g., a chin implant that lies obliquely to or off the midline), but it also can cause problematic asymmetry when paired implants are employed (e.g., malar implants may be differently positioned). Malposition can result from an improperly sized pocket or inadequately secured implant3 (Fig. 12.1). Pocket inadequacy or an excessively sized implant may cause pressure necrosis of the overlying skin/soft tissue envelope, resulting in exposure and eventual extrusion. A displaced implant needs to be repositioned expeditiously. Extrusion can also occur from an infected implant. Extrusion warrants implant removal, with possible reinsertion once the extrusion site is completely healed.6 Persistent seromas tend to occur most often with Silastic (silicone) implants and may need to be drained repeatedly.8 The exact pathophysiology of seroma formation after silicone implantation is unclear. Infection can occur with any implantation procedure but may be more common with intraoral approaches. Some studies suggest that soaking the implant in an antibiotic solution (Bacitracin 50,000 units in 1 liter of normal saline) and using perioperative antibiotics may decrease the incidence of implant-related infections.3 Should an infection occur, aggressive antibiotic therapy with grampositive and anaerobic coverage is indicated. Commonly cultured organisms include staphylococcal and streptoccoccal species and anaerobes. Certain implants with good vascular ingrowth may be salvageable (such as Gore-Tex and MEDPOR) with antibacterial therapy, but infection frequently requires removal of the implant. Fig. 12.1 Coronal CT of the face revealing significant displacement of a 10-year-old Silastic malar implant. The patient was experiencing right facial swelling, discomfort, and other symptoms consistent with unilateral maxillary sinusitis. Physical examination also revealed a 3 mm oroantral fistula on the affected side. In addition to the displaced implant, the CT also illustrates soft tissue near the right maxillary ostium (star), which was consistent with polypoid degeneration seen on nasal endoscopy. The fistula tract is also partially visualized on CT (arrow). Preventive measures to help reduce the incidence of such complications include timely cessation of aspirin, anticoagulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), vitamins (especially vitamin E), and herbal medications. As long as it is cleared with the patient’s primary physician, patients should be off these medications long enough to return the blood clotting cascade or platelet function to normal. Most commonly, two weeks before surgery is sufficient. Steroids are commonly administered intraoperatively, and continued for 24 hours perioperatively to decrease postoperative edema. Similarly, an appropriate intravenous dose of a first-generation cephalosporin or clindamycin should be administered (ideally 30 minutes before the initial incision), and perioperative antibiotics (again, with good gram-positive and anaerobic coverage) are prescribed for five days. A pressure dressing can be helpful for the first 24–48 hours after any implantation procedure to decrease the risk of a hematoma and limit edema. Patients are additionally instructed to elevate their heads and to use cold compresses on the surgical site for the first 48 hours after surgery. Implant-related complications tend to vary with the implant material used and site of implantation. As previously indicated, implant and host factors are interrelated. Common implant-related problems include inflammation, edema, displacement, infection, exposure, extrusion and bone resorption. Rare complications include the potential risk of carcinogenicity, but the level of this risk is ill-defined in the literature. Silicone, in particular, has been implicated as an etiologic factor in certain connective tissue diseases, yet several large series show no increased risk in women following silicone breast augmentation.4

Complications with Facial Implantation

The Ideal Facial Implant

The Ideal Facial Implant

Implant Complications

Implant Complications

Patient-Related Complications

Complications Related to Surgical Technique

Hematoma

Nerve Injury

Prolonged Edema

Implant Migration and Extrusion

Persistent Seromas

Infection

Implant-Related Complications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree