Fig. 35.1

Total flap loss

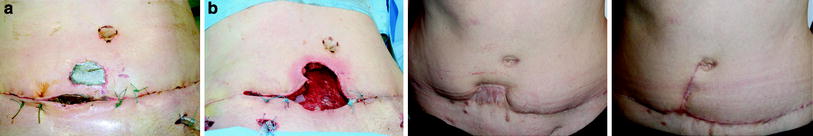

Apart from high-risk situations (smoking, obese, or diabetic patients), which are for some only relative contraindications to unipedicled TRAM flap reconstruction, significant necrosis of the flap can occur owing to a technical error during the intraoperative harvesting injuring the superior epigastric vessels as in following case. This was an obese patient of 52 years of age for whom unipedicled TRAM flap reconstruction was chosen despite a BMI of 31 to correct a faulty immediate reconstruction with an expander (infection). The operation was marked by a spontaneous and complete tear of one of the two pedicles of the upper division epigastric vessels before it entered the posterior face of the right rectus abdominis muscle. This occurred as a result of traction on the pedicle (which was attached to the rib cage) by the particularly heavy flap of this patient while it was being shifted upward. Microsurgical repair of the injured pedicle (artery and vein) was performed to save the flap, but partially failed. Further surgery was done 48 h later to resect about 25 % of skin tissue developing necrosis (Fig. 35.2a), with good progress after 1 month (Fig. 35.2b) but fat melting was recorded later (Fig. 35.2c). In these situations of significant loss of surface and volume of the flap, the secondary correction requires the use of a prosthesis or another flap. A proposal for recovery with an autologous latissimus dorsi flap associated with lipofilling was made to the patient.

Fig. 35.2

a Resection of thrombosed tissues after 48 h. b Result after 1 month. c Result after 1 year and fat melting

35.2.1.2 Moderate Flap Loss (Between 5 and 25 % of the Flap)

This complication occurs more frequently, from 3 to 15 % in published series [11, 12]. Early treatment is performed to save as much as of the flap as possible and a later treatment is proposed to correct the sequelae of this necrosis.

Often related to venous congestion (which will be the cause of necrosis), an established necrosis requires us to perform further surgery on the second postoperative day when the limits of the cutaneous vein thrombosis are well marked and before thrombosis spreads to a larger portion of the flap. It is generally found in patients whose blood supply to the flap was overestimated intraoperatively, especially in its periphery and the side opposite the pedicle muscle. In this case the removal of thrombosed tissue requires a complete remodeling of the flap, which is easy to perform on the second postoperative day before scar tissue fibrosis occurs as is shown in the case in Fig. 35.3.

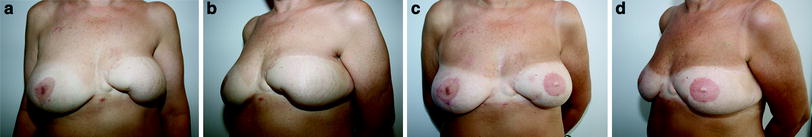

Fig. 35.3

a, b Images showing the thrombosed tissues after 48 h. c Removal of thrombosed tissues and complete remodeling of the flap. d Result 9 months later

It is better to intervene early rather than let necrosis evolve naturally, for several reasons:

Early intervention saves more volume of the flap (before the necrosis spreads).

Spontaneous evolution of the necrosis can last several months with important localized health treatment, which can lower the patient’s morale.

In some cases there is a risk of infection of necrotic tissue that may extend to the whole flap.

The final result with a retractile fibrosis and a defect located on the edge of the flap is more difficult to correct than one treated after an early intervention leaving the residual flap smoother.

The necessary correction in the long run may call for a prosthesis or another flap to make up the volume. If the patient has suitable donor areas, a correction of the flap can be done more simply by skin remodeling associated with lipofilling and symmetrization of the contralateral breast and without (Fig. 35.4) or with (Fig. 35.5) remodeling of the flap.

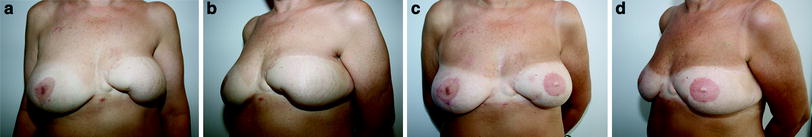

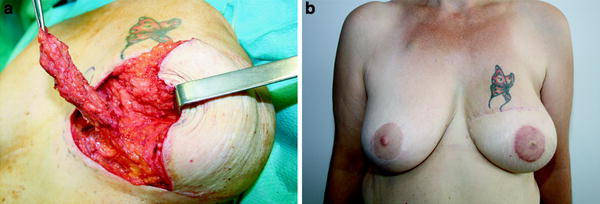

Fig. 35.4

a Frontal view and b oblique view 1 year after necrosis of both extremities of the flap. c Frontal view and d oblique view after two lipofillings (140 and 120 cm3) and nipple–areola reconstruction

Fig. 35.5

a Frontal view and b oblique view 7 years after necrosis of the inferointernal region of the flap. c Frontal view and d oblique view after remodeling of the flap, two lipofillings (110 and 160 cm3), nipple–areola reconstruction, and reduction of the contralateral breast (170 g)

35.2.1.3 Minimal Skin Necrosis (Less Than 5 % of the Flap)

This does not require early new surgery. Its boundaries are difficult to assess in the first few days after surgery and can be treated by allowing the lesion to evolve spontaneously as postoperative care is then simple and can be done by the patient herself without too much trouble. It leaves a zone of residual underlying fat necrosis. It is often associated with a small skin necrosis of the abdominal scar, reflecting a general vascular status of the patient that is not optimal.

35.2.2 Fat Necrosis

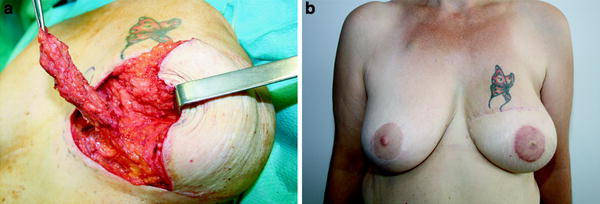

Fat necrosis is associated with skin necrosis but can also occur without evidence of skin necrosis. Its frequency ranges from 4 to 35 % depending on the series [7, 13, 14]. It is troublesome if it is large and the cause of a large induration perceived by the patient. It can, as in the case shown in Fig. 35.6, be corrected by an excision followed by remodeling of the flap done in conjunction with the areolar reconstruction.

Fig. 35.6

a Removal of internal fat necrosis (10 × 2 × 1.5 cm), remodeling of the flap, and areola reconstruction 8 months after transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap reconstruction. b Result 8 months later

If the fat necrosis cannot be resected without distorting the reconstruction, or if it is minimal, it can be left in place with reassurance given to the patient. A simple lipofilling can potentially improve the consistency of the flap or remove a superficial skin retraction.

35.2.3 The Parietal Complications

35.2.3.1 Mechanical

All types of complications can occur following a relaxation of the fascial suture in 4–29 % of cases depending on the series [15–17].

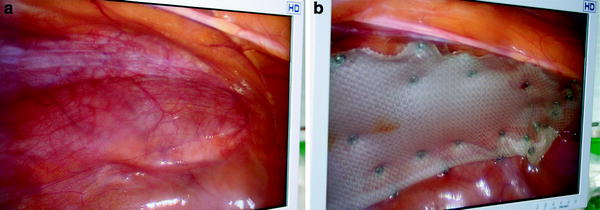

The most troublesome are the abdominal hernias, which can be localized in the epigastric region (transition zone of the flap) or below the umbilical region (area of weakness below the arcuate line). They should be treated as if they are symptomatic. The placement of a mesh by laparoscopy is the most elegant treatment (Fig. 35.7).

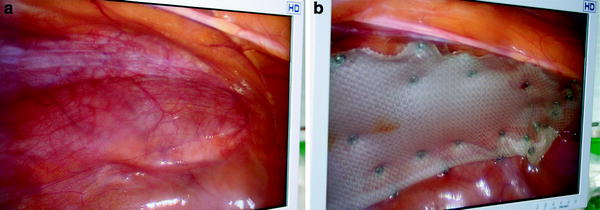

Fig. 35.7

a Laparoscopic view showing abdominal infraumbilical hernia 2 years after unipedicled TRAM flap reconstruction without preaponeurotic mesh. b Repair using intraperitoneal mesh

The commonest complication is weakness of the fascia in the infraumbilical region (laxity or bulge), which can be corrected later, if the patient wishes, by a complete detachment of the wall followed by plication of the fascia (for re-tension) and the establishment of a reinforcing preaponeurotic mesh.

35.2.3.2 Infections

Infections of the flap are rare outside necrosis cases.

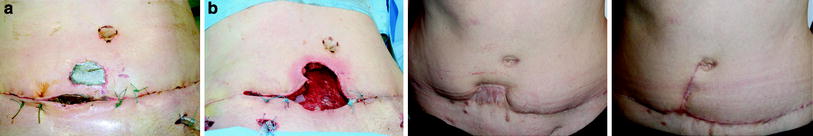

Acute and significant postoperative infections of the abdominal wall require removal of the prefascia mesh, followed by monitored wound healing and later cosmetic correction away from the abdominal scar (Fig. 35.8).

Fig. 35.8

a Drainage of acute infection with anaerobic germs of the abdominal infraumbilical skin 8 days after TRAM flap reconstruction. b Removal of the infected tissues and the prefascia mesh 15 days after TRAM flap reconstruction. c Result 6 months later, after important localized health treatment. d Result 1 year later after correction of the scarring sequelae

Infections of the abdominal wall in relation to a dehiscence abdominal scar after a deficit of blood supply to the lips are handled by local treatment without removal of the parietal prosthesis.

Some infections such as those occurring away from a hematoma or seroma of the abdominal wall can cause a chronic skin fistula problem. If the prosthesis located deep in the sheath of the right rectus abdominis muscle is affected by germs, superficial debridement of the wound, even combined with appropriate antibiotic therapy, is inadequate. The final treatment of the infection requires removal of the underlying contaminated prosthesis, which can weaken the wall, with a risk of secondary eventration. The use of a dermal matrix prosthesis can be of great help to obtain proper healing and a solid wall in a septic environment.

35.3 Our Series

We performed 192 unipedicled TRAM flap reconstructions in our unit between October 2003 and October 2009. I participated as a principal surgeon (in most cases) or as an assistant. The analysis was done from medical records (hospitalization and outpatient) and also from questionnaires sent to patients (77 % responded). In our experience, unipedicled TRAM flap reconstruction is the preferred secondary breast reconstruction technique when the morphology of the patient permits. In some cases it is done by default, even if the morphology of the patient is not ideal (with a flap of moderate size) owing to the impossibility of making a prosthesis for breast reconstruction and weighing the pros and cons with respect to the use of a latissimus dorsi flap. The patient is then warned of the risk of postoperative prolonged tension of the abdominal wall.

When possible, we use the unipedicled TRAM flap by a taking a sample of the contralateral right rectus abdominis muscle. Preparation by ligation of inferior epigastric vessels is routinely performed at least 3 months before the completion of the TRAM flap reconstruction.

We do not often use TRAM flap reconstruction for immediate reconstruction (3 % of cases), given the risk of additional treatment in cases of invasive cancer. We also systematically insist on a 3-month period after preparation, and it is difficult to delay a mastectomy for cancer, even in situ, for that period of time. Our immediate TRAM flap reconstruction involves prophylactic mastectomy.

In this series, the rate of specific complications was low. As shown in Table 35.1, there were six cases of flap necrosis (3 %), of which three cases were necroses greater than 5 % requiring further surgery: one for an intraoperative problem already described (Fig. 35.2) and two related to the overevaluation of the intraoperative vascularization of the flap, treated by removal of areas of necrosis at 48 h, with subsequent correction of asymmetry.

Table 35.1

Cases of necrosis observed (among 192 cases)

Flap loss > 25 % | 1 case |

Flap loss of 5–25 % | 2 cases |

Flap loss < 5 % | 3 cases |

Fat necrosis < 10 % | 17 cases |

As shown in Table 35.2, there were nine cases of mechanical complications of the wall (4.5 %), of which six cases were bulges and three cases were abdominal hernia requiring further surgery by laparoscopy(1.5 %).

Table 35.2

Cases of mechanical complications observed

Abdominal hernia | 3 cases |

Abdominal laxity | 6 cases |

Five infections of the abdominal wall, of which two of the more important required removal of the preaponeurotic mesh, had to be treated

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree