Repair of the cleft palate intends to establish the division between the oral and nasal cavity, thereby improving feeding, speech, and eustachian tube dysfunction all while minimizing the negative impact on maxillary growth. Before palate repair candidacy, timing and surgical method of repair is dependent on comorbid conditions, particularly cardiac disease, mandibular length, and palate width. Additionally, management of the alveolar cleft and the indications for gingivoperiosteoplasty versus secondary alveolar bone grafting is a controversial topic that weighs the risks and benefits of potentially sparing the patient an additional surgery against iatrogenic restriction of facial growth and malocclusion.

Key points

- •

A multidisciplinary approach is essential in providing the best care for patients with a cleft palate.

- •

The type and width of the cleft palate determine the appropriate surgical palatoplasty technique to adequately achieve a tension-free and multilayered closure with repositioning of the velar muscle sling.

- •

Intravelar veloplasty is a critical step during palatoplasty to ensure that children have proper velopharyngeal closure.

- •

Use of adjunctive surgical techniques and biologic materials can decrease the occurrence of fistula formation.

Introduction

The primary goal of cleft care is to optimize function and appearance while minimizing surgical interventions and complications. Although cleft palate usually is an isolated finding, greater than 30% may have additional comorbidities or an associated syndrome, which must be considered and may affect surgical candidacy, overall prognosis, and surgical outcomes. There are numerous surgical techniques that may be chosen based on cleft classification, cleft width, and surgeon experience and preference. Management and repair of the alveolar cleft is also an important aspect of care and secondary bone grafting is often required to treat alveolar defects. Primary gingivoperiosteoplasty (GPP) closes the alveolar cleft at the time of cleft lip repair, decreasing the likelihood for alveolar bone graft, although it has produced inconsistent results and is controversial. It is essential to recognize and address the emotional and psychological needs of the family, at birth and before surgical care. Overall, assessment and treatment of those with cleft lip and/or palate requires a multidisciplinary team approach.

Genetics and Prenatal Diagnosis

Cleft lip and/or palate is the most common congenital malformation of the head and neck and occurs in the setting of multiple genetic and environmental factors. The condition is linked to more than 400 genes, occurs in an autosomal-dominant or autosomal-recessive or nonmendelian inheritance pattern, and most (70%) patients present without an associated syndrome.

As genetic advances continue it is necessary to counsel expecting families on advanced diagnostic options available for future children. Ultrasound screening is routinely done in the first trimester to document viability, although the fetal face is typically not imaged adequately at this time. Three-dimensional ultrasound images of the face were first obtained in 1986 and became widely used in the mid-1990s, prenatally identifying many more cleft lip and palate patients. In 2000 this technology was used for multiplanar volume rendering and the 2007 American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine Guidelines for Prenatal Ultrasound Screening require the fetal face to be imaged in the second trimester. Addition of four-dimensional ultrasounds has improved accuracy, although diagnosing an isolated cleft palate remains difficult and false-positives may occur because of shadowing.

Classification

Multiple classification schemes have been created for orofacial clefts. These models are usually based on several features of the cleft including laterality, completeness, severity (wide vs narrow), and presence of any abnormal tissue. Diminutive orofacial clefts may also be described as microform, occult, or minor. Laterality is described as being either unilateral or bilateral. A complete cleft lip extends through the lip and the nasal sill and an incomplete cleft lip extends only through the lower part of the lip with some intact lip tissue above the cleft. The cleft alveolus can be considered complete or only notched. Weblike tissue may extend from the lip’s cleft side to the noncleft side at the nasal sill, which is termed a Simonart band and is not equivalent to an incomplete cleft. A cleft palate is unilateral if one palatal shelf attaches to the nasal septum, or bilateral. The four group classification scheme introduced by Veau is the most frequently used system:

- •

Group I: defect of the soft palate only.

- •

Group II: defect involves the soft palate and the hard palate to the incisive foramen.

- •

Group III: unilateral defect extending through the entire palate and alveolus.

- •

Group IV: bilateral complete cleft.

Introduction

The primary goal of cleft care is to optimize function and appearance while minimizing surgical interventions and complications. Although cleft palate usually is an isolated finding, greater than 30% may have additional comorbidities or an associated syndrome, which must be considered and may affect surgical candidacy, overall prognosis, and surgical outcomes. There are numerous surgical techniques that may be chosen based on cleft classification, cleft width, and surgeon experience and preference. Management and repair of the alveolar cleft is also an important aspect of care and secondary bone grafting is often required to treat alveolar defects. Primary gingivoperiosteoplasty (GPP) closes the alveolar cleft at the time of cleft lip repair, decreasing the likelihood for alveolar bone graft, although it has produced inconsistent results and is controversial. It is essential to recognize and address the emotional and psychological needs of the family, at birth and before surgical care. Overall, assessment and treatment of those with cleft lip and/or palate requires a multidisciplinary team approach.

Genetics and Prenatal Diagnosis

Cleft lip and/or palate is the most common congenital malformation of the head and neck and occurs in the setting of multiple genetic and environmental factors. The condition is linked to more than 400 genes, occurs in an autosomal-dominant or autosomal-recessive or nonmendelian inheritance pattern, and most (70%) patients present without an associated syndrome.

As genetic advances continue it is necessary to counsel expecting families on advanced diagnostic options available for future children. Ultrasound screening is routinely done in the first trimester to document viability, although the fetal face is typically not imaged adequately at this time. Three-dimensional ultrasound images of the face were first obtained in 1986 and became widely used in the mid-1990s, prenatally identifying many more cleft lip and palate patients. In 2000 this technology was used for multiplanar volume rendering and the 2007 American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine Guidelines for Prenatal Ultrasound Screening require the fetal face to be imaged in the second trimester. Addition of four-dimensional ultrasounds has improved accuracy, although diagnosing an isolated cleft palate remains difficult and false-positives may occur because of shadowing.

Classification

Multiple classification schemes have been created for orofacial clefts. These models are usually based on several features of the cleft including laterality, completeness, severity (wide vs narrow), and presence of any abnormal tissue. Diminutive orofacial clefts may also be described as microform, occult, or minor. Laterality is described as being either unilateral or bilateral. A complete cleft lip extends through the lip and the nasal sill and an incomplete cleft lip extends only through the lower part of the lip with some intact lip tissue above the cleft. The cleft alveolus can be considered complete or only notched. Weblike tissue may extend from the lip’s cleft side to the noncleft side at the nasal sill, which is termed a Simonart band and is not equivalent to an incomplete cleft. A cleft palate is unilateral if one palatal shelf attaches to the nasal septum, or bilateral. The four group classification scheme introduced by Veau is the most frequently used system:

- •

Group I: defect of the soft palate only.

- •

Group II: defect involves the soft palate and the hard palate to the incisive foramen.

- •

Group III: unilateral defect extending through the entire palate and alveolus.

- •

Group IV: bilateral complete cleft.

Patient assessment

Multidisciplinary Care

A multidisciplinary approach should be used when addressing these patients to achieve optimal outcomes. The team includes initial evaluations by a pediatrician, geneticist, surgeon, feeding specialist, social worker, and possibly others. The children also need to be seen by audiology, otolaryngology, dental, oral surgery, and speech pathology after the initial visit. Prenatal surgical consultation with the surgeon, geneticist, and speech pathologist before birth is recommended to alleviate some of the anxiety parents may be experiencing.

Surgical Assessment

A thorough physical examination is necessary soon after birth. This should include special attention to the upper lip, alveolar arches, nostrils, primary and secondary palates, nasal alar symmetry, tip projection, alar base position, and width, and any signs of dysmorphia that may lead to identification of additional congenital anomalies or syndromes. Any concern for cardiac or airway issues must be identified and assessed before surgical intervention. Specific evaluation for microform cleft lip and submucosal cleft palate, even considering ultrasound evaluation, is important because their presentation is overlooked due to subtle findings on examination. Regular clinic visits after birth allow proper counseling and guidance to the patient’s caretakers and the surgeon may need to place several referrals to any necessary specialists.

Primary repair of cleft palate

Preoperative Planning and Considerations

The preoperative evaluation is the same as for a child with a cleft lip, although it is particularly important that the caretakers understand proper feeding methods. Cleft palate may also lead to airway obstruction, therefore any airway concerns must be addressed before surgery. The type and width of the cleft must be accurately determined to select the appropriate surgical technique. Of note, patients with a submucous cleft palate may be closely monitored without intervention and only surgically repaired if they develop speech, feeding, or otologic difficulties.

Timing of Repair

The customary timing of cleft palate repair is before 18 months, with the ideal time being 10 to 12 months of age to avoid poor speech and language development associated with delayed repair. Early palate repair must be weighed against the concern of negatively affecting the patient’s maxillary growth that may occur with an earlier repair.

Patient Positioning

Positioning is similar for all techniques described next. The patient is placed supine on the operating table usually on a shoulder roll for gentle cervical extension, unless the patient has a syndrome associated with spinal abnormalities. Intubation is with either a standard endotracheal tube or a right angle endotracheal tube that is secured in the midline to the chin. Patients with midface hypoplasia and micrognathia may be difficult to intubate before surgery and experience postoperative airway obstruction; therefore, it is important for the surgical team to communicate concerns and discuss postoperative airway management. Tegaderms are used for eye protection. The surgical bed is rotated at least 90° from the anesthesiologist. Intravenous antibiotics are administered, surgical site is draped, a Dingman mouth retractor ( Fig. 1 ) is used to achieve adequate visualization, and the palate is injected with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine.

Surgical Techniques

The main principles of palatoplasty consist of a tension-free and multilayered closure with repositioning of the velar muscle sling. Several techniques along with modifications exist, and the most commonly performed options are described next.

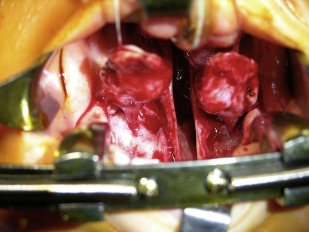

Two-flap palatoplasty

The two-flap palatoplasty is a widely used technique that is indicated for the closure of complete unilateral and bilateral clefts of the primary and secondary palate. This technique permits easy exposure of the soft tissue musculature that allows release of anomalous attachments of the levator veli palatini to complete an intravelar veloplasty and reorient the levator sling horizontally. Incisions are marked from the tip of the uvula medially along the cleft margin toward midline of the alveolus. The alveolar ridge is then followed posteriorly to the end of the alveolus where a small releasing incision is made. When making the incision along the cleft margin medially it is important to stay 1 mm to 2 mm toward the oral mucosa to ensure a suitable mucosal flap for a tension-free nasal closure. After the incision is complete attention is turned to raising palatal flaps in a subperiosteal plane until there is complete exposure of the hard-soft palate junction, taking care to identify and preserve the greater palatine artery ( Fig. 2 ). The greater palatine neurovascular bundle that supplies each flap is encountered and preserved while the foramina fascia should be released to assist with medial advancement of the flap. Osteotomies may also be made through the posterior foramina of the hard palate in significantly wide cleft palates (>20 mm) while meticulously avoiding injury to the bundle itself. Starting medially the abnormal levator muscle attachments are released from their attachment at the posterior edge of the hard palate and cleft margin. The nasal mucosa is also raised off of the superior surface of the hard palate and extended into the soft palate. Muscle fibers are released laterally until the hamulus and tensor veli palatini muscle are seen. One must check all flaps (nasal mucosa, musculature, and oral layer) for adequate length. Vomer flaps are elevated on one side only in a unilateral cleft palate but bilaterally in bilateral cleft palates to decrease the tension on the nasal layer closure.

The nasal layer of the uvula is then closed with horizontal mattress sutures using a 4–0 Vicryl on a TF needle. The remainder of the nasal layer is then closed with simple interrupted sutures using a 4–0 Vicryl on a PS-4c needle burying the knots on the nasal layer ( Fig. 3 ). If there is excessive tension on the nasal closure, the central sutures are placed after the muscle layer is approximated to decrease tension. The levator muscle is sutured to create an intravelar veloplasty with a 3–0 Vicryl on an RB1 needle in an interrupted mattress fashion. Once the nasal layer and levator sling are closed, the oral layer is closed with simple interrupted sutures starting at the base of the uvula and moving anteriorly with 4–0 Vicryl on a TF needle. When the hard palate is reached a switch is made to horizontal mattress sutures and to capture some of the nasal mucosa to obliterate the dead space ( Fig. 4 ). Once completely closed, hemostasis is achieved and microfibrillar collagen hemostatic agent is placed in the open defects laterally. If there is concern for airway obstruction, one may place a tongue traction stitch. Also, if the cleft is more than 2 cm acellular dermal matrix may be used between the nasal and oral layers at the junction of the soft palate and hard palate as reinforcement to reduce fistula formation.