Fig 13.1

Appearance of hand allograft prior to required amputation in patient 4

A Rose Is Not a Rose

Unlike the experience in solid organ transplantation, it appears that chronic rejection may manifest in several different ways in VCA recipients. We have discussed the aggressive, confluent, concentric graft vasculopathy that was seen in patients 4 and 6 at our center. All arteries in the graft were involved from the ulnar and radial arteries to the digital arteries, and there was thickening of venous walls as well. In contrast, we have also seen a focal, sometimes acentric vasculopathy that is found in some but not all arteries in the graft, and progresses very slowly. We have mapped specific lesions in some of our patients that have not changed significantly in 3 years of follow-up. In some cases these thickened areas are in the digital arteries, and in some cases are in the ulnar arteries. While these focal lesions do not appear to change significantly over time, there is a clear distinction in most of our unilateral recipients between the transplanted hand and the native hand. The vessel walls have sharper images and are easier to view than the transplanted hand which has slightly thicker vessel walls in general compared to the native hand. This is not true for everyone. In patient 7, who has a unilateral transplant, but who has a native hand that endured significant damage in the original accident, it is easier to image by UBM in his transplanted hand than his native hand. In the eight hand transplant recipients transplanted at our center, two recipients have had multiple significant acute rejection episodes in the skin component of the graft, both in the first-year posttransplant and many years posttransplant. Most would predict that these two patients might have the greatest level of graft vasculopathy, and might suffer from the more confluent variety. That has not been our experience. Our second patient, who is now more than 12 years posttransplant has had eight episodes of biopsy proven skin rejection of grade 2 or higher. Our third patient has had at least 12 episodes of grade 2 or higher rejection. Both of these patients have shown minimal changes in their vessels over the past 3 years, with very good blood flow, excellent digital temperatures, and no obvious changes in vessel wall thickness by UBM imaging.

In contrast, patients 4 and 6 had relatively quiet courses with respect to skin rejection (Table 13.1). In these patients, the vasculopathy quickly escalated to the point the graft was lost to ischemia in patient 4, and without intervention, patient 6 may have lost his graft as well. The other patients to date have areas of vascular thickening, but it has not progressed noticeably, and in none of these cases does the vasculopathy seem to be affecting either blood flow or graft function in the slightest. Both forms are a type of vasculopathy, but they do not appear to be similar in any respect other than both are thickening of the vessels restricted to the graft. A similar variance in presentation is seen in other transplant vasculopathies. In cardiac transplantation, 50 % of all patients develop graft vascular disease (GVD) within 12 months, one third of which is rapidly progressive [36, 57]. The lack of correlation between skin rejection and vasculopathy is supported by recent observations in a nonhuman primate model of face transplantation [39]. In this model, animals that lost their graft upon cessation of immunosuppression also developed a near occlusive intimal thickening, and the grafts were edematous and pale, supporting a restriction of blood flow. Superficial punch skin biopsies in these animals also failed to show evidence of immunologic rejection despite a restriction of the vasculopathy to the graft vessels. Interestingly, biopsy of deeper tissues revealed an active immune response, with development of tertiary lymphoid follicles [39]. In our clinical experience, both patients with aggressive vasculopathy had surface skin biopsies that were negative for cellular infiltrates. The histology of deep tissue in the amputated graft did reveal significant infiltrates in the deeper tissues. Whether that was due to a rejection process, or severe ischemia, or both is unknown. Like our clinical experience, in the primate face transplant model antibodies did not appear to play a role in the vasculopathy. There was no immunoglobulin (Ig)G or IgM alloantibody production that correlated with intimal hyperplasia, and staining for C4d deposition was negative in both the thickened vessels and the tertiary lymphoid follicles. In our clinical trial, we saw nonspecific staining of C4d in both skin punch and deep tissue biopsies. Of note, with the exception of patient 2 who developed donor-specific antibodies (C1q negative) at year 6, none of our patients have evidence of donor-directed HLA-specific alloantibodies (DSAs). In patient 4, DSAs were negative up to and at the time of amputation , but DSAs were detected 2 days after amputation and 4 days after immunosuppression was stopped. Similar conversions to a positive DSA after graft removal have been shown in renal transplants [9]. Landin et al. have also reported that development of donor-specific antibodies does not necessarily correlate with staining of C4d on skin biopsies [31]. Kanitakis et al. examined C4d expression in four VCA recipients and found no evidence of C4d staining, despite development of DSA antibodies [25]. Dr. Anthony J. Demetris at the University of Pittsburgh has suggested that staining of vessels within adipose tissue might reduce the nonspecific staining and allow us to detect an active humoral response to the donor. Mundinger et al. reported that in their nonhuman primate model, Notch pathway receptors 1, 3, and 4 and Notch pathway ligand Jagged-1 were upregulated specifically in the areas of large vessel intimal hyperplasia compared to unaffected control vessels, suggesting this may be an important pathway in the development of graft vasculopathy [39].

Table 13.1

Lack of association of skin allograft rejection and vasculopathy

Nonvascular Targets of Chronic Rejection in VCA Recipients

The graft loss from ischemia and evidence for at least some vascular thickening in comparison to the native hand in 100 % of our recipients is strong evidence that the vasculature may be a target of chronic rejection in hand transplant recipients . We and others hypothesized that the skin would be a primary target of chronic rejection, and data from experimental models and our own patients support this. Unadkat et al. have shown in a model of rat hind limb transplantation with multiple episodes of acute rejection that both the vasculature and other tissue show signs of chronic rejection (skin atrophy and fibrosis, as well as muscle atrophy and infiltration [58]). In this model, the experimental group received cyclosporine A in an irregular manner to simulate noncompliance, and rejection episodes were repeatedly treated, and animals were allowed to reject again. The investigators then followed the animals to determine the effect of multiple rejection episodes on the development of chronic rejection as defined by vasculopathy and skin and tissue changes. Animals with multiple episodes of acute rejection showed patchy hair loss with dermal atrophy and apoptotic bodies in the sebaceous glands and hair follicles demonstrating adnexal structure involvement. The dermis was thinner, however, fibrosis at the epidermo-dermal juncture resulted in significantly thicker skin in the multiple Acute Rejection (AR) animals [58]. Changes were also seen in muscle and there was an increase in osseous malunion in the multiple AR group. This association of multiple AR episodes with increased incidence of chronic rejection makes immunologic sense. Correlation of acute rejection and increased risk of chronic rejection is well documented in solid organ transplantation [41, 59, 60]. As previously stated, reports of chronic rejection directed at skin or tissue other than the vasculature have been rare in clinical VCA recipients. Careful assessment of five hand and face recipients from 10 to 2 years posttransplant failed to produce any evidence of changes in the skin or vessels, or decreases in function or sensorimotor recovery [44]. The authors suggest that strict adherence to triple-drug immunosuppression without attempts to wean or minimize may have contributed to freedom from evidence of chronic rejection [44]. A trend toward higher immunosuppression may contribute, however, other groups who have implemented immunosuppression minimization have not reported issues with chronic rejection in compliant patients to date either [3]. In fact, no center has reported loss of a VCA graft due to skin rejection in a compliant patient.

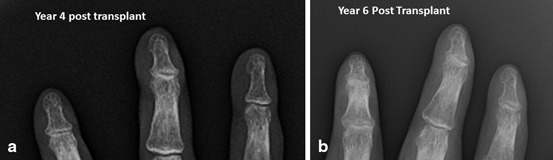

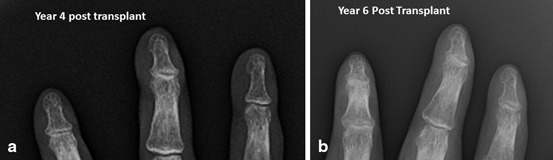

Recently, our center reported what appears to be evidence of chronic changes in the skin and adnexal structures of our third hand transplant patient who is now 6 years posttransplant [26]. Our third recipient received his unilateral graft in 2006. At year 4, the patient presented with thinning of the digits and partial loss of fingernails on the transplanted hand. At presentation, overexposure to topical steroids was suspected. Fungal scrapings were negative and skin biopsies were negative for fibrosis. At year 5, he presented with complete loss of the nails and thinning of the skin as well as a noticeable rash on the skin. Radiographs of the hand at years 4 (Fig. 13.2a) and 6 (Fig. 13.2b) were unremarkable for loss of bone in the digits, but loss of soft tissue especially at the tips was noted in year 6 (Fig. 13.2). Electromyography (EMG) conductivity is reduced at year 6. Figure 13.3 shows the changes in his skin and nails between year 2 and year 6. Significant changes in the nails were noted in year 4 (Fig. 13.3b), and the nails disappeared by year 5 (Fig. 13.3c). This subject is notable for a preexisting and stable marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) diagnosed 18 months posttransplant. The patient is also notable for multiple episodes of skin rejection over the previous 6 years, with biopsies of histologic grade 2 or higher. Note that these rejections are in the face of good compliance with immunosuppressive medications. This patient is also remarkable in that while skin atrophy is present, skin biopsies to date have been negative for significant fibrosis, in contrast to the histology found in the nonhuman primate model of face transplantation [39]. Scleroderma patients have been proposed as a good model to study for chronic rejection in VCA [50]. To date, our center has not seen a VCA recipient that resembles a scleroderma patient. Antibodies do not seem to be a major initiating factor. Fibrosis and/or collagen deposition has not been a factor in either acute or chronic rejection in our patients or those of our colleagues. The field of VCA is young, and there may be a subpopulation of VCA patients with chronic rejection that resembles scleroderma. But to date, this has not been our experience.

Fig 13.2

(a) Radiograph of fingertips of patient 3 at year 4, (b) and at year 6 posttransplant. Note the reduction of soft tissue at the tips of the fingers at year 6

Fig 13.3

Changes in appearance, skin thinning, and loss of adnexal structures over time in patient 3. a Year 2 posttransplant; b year 4; c year 5; d year 6. Note the complete loss of fingernails by year 5 and 6 posttransplant

Potential Causes of Chronic Rejection in VCA Transplantation

It is clear that nonimmune components as well as allogeneic responses contribute to vasculopathy and chronic rejection in solid organ transplantation [2, 12, 37]. The nonimmune aspects which are unique to VCA include mechanical and traumatic stress to the graft and possibly surgical techniques such as the long donor brachial artery harvest. However, mechanical stress alone and/or long artery harvest cannot be sufficient for development of vasculopathy. Patients transplanted previously and subsequently at our center who also routinely stress their grafts mechanically in manual labor and who have received a graft with a long brachial artery did not develop aggressive vasculopathy [52]. We believe that the aggressive vasculopathy we have seen in our patients is due to a “perfect storm” of both alloimmune and nonimmune factors. Our data and the data from other centers and from experimental models suggest that there may be multiple types or targets of chronic rejection in VCA grafts. We hypothesize that the four major types of chronic rejection in VCA recipients are: (1) aggressive confluent graft vasculopathy, (2) focal slowly progressing graft vasculopathy, (3) chronic rejection of the skin, with atrophy of the skin and underlying muscle, loss of adnexal structures such as fingernails, hair follicles, and sebeaucous glands, and (4) a classic chronic rejection of the skin with dermal atrophy, loss of adnexal structures, and thickening of the skin due to fibrosis. As clinical and experimental evidence accumulates, the first type of graft vasculopathy may turn out to be more of an acute type of rejection rather than a chronic rejection. We were encouraged by the fact that this type of vasculopathy was receptive to treatment. The more indolent type of vasculopathy may not be amenable to treatment. However, we would predict that few grafts would be lost to this much more focal and slowly progressing form.

There are multiple factors that can induce intimal hyperplasia and vasculopathy. Trauma alone can induce intimal hyperplasia [7, 36]. Any mechanical, cytotoxic, immunologic, and thermal injury that might result in endothelial damage can in turn initiate and propagate intimal hyperplasia [15, 36], as well as remodeling [37]. Recently, Christensen et al. reported that repeated rubbing of cage wire induced episodes of rejection in a swine model of hind limb transplantation [7]. In a rat model of sustained thrombocytopenia after injury, restoration of platelets even 2 weeks after injury can trigger smooth muscle cell proliferation [49]. Factors such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) have also been shown to induce vasculopathy [42]. In the face of these stimuli, and when allogeneic immune responses are also occurring, a situation that is conducive to the development of chronic rejection is created. Patient 4 who lost his graft received less immunosuppression than the first two patients who have done well clinically and with respect to vasculopathy. This patient also prided himself on the aggressive use of his allograft. It is not possible to know for sure, but one can hypothesize both of these scenarios contributed to the aggressive vasculopathy and loss of the graft. This hypothesis was the impetus for starting patient 6 on standard triple-drug immunosuppression. Nonetheless, patient 6 also developed severe vasculopathy despite conventional levels of immunosuppression (induction, followed by triple-drug therapy with maintenance steroids). This patient had wound coverage issues and infectious complications requiring multiple surgical debridements. This level of mechanical trauma could also have contributed to his aggressive vasculopathy.

Diagnosis/Monitoring of Chronic Rejection in VCA

Most VCA programs have excellent monitoring protocols which involve testing blood levels of immunosuppressive drugs, frequent interactions with nurse coordinators to discuss clinical changes and problems, protocol skin biopsies, and annual monitoring of vascular changes by digital brachial indices, MR or CT angiography, and CT scans. Sensorimotor function and EMG changes are also monitored. Based on our experience, we highly recommend that programs implement vascular monitoring using high-resolution ultrasound imaging . Ideally, centers should have access to an ultrasound unit with probes of at least 20–40 mHz. If smaller vessels such as the digital arteries will be monitored, probes of 50–70 mHz are recommended. Note that the higher resolution probes are not effective for vessels more than a centimeter or so under the skin. Our established recipients who are doing well are monitored on an annual basis, and recent transplant recipients are monitored monthly or as clinical course indicates.

Treatment of Chronic Rejection

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree