Chronic Pain Syndromes

George D. Chloros

L. Andrew Koman

Zhongyu John Li

Thomas L. Smith

I. Introduction

Pain is defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage” by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Chronic extremity pain, which persists in the absence of ongoing cellular injury or compromise and extends beyond the injured area or distribution of the involved nerve, is termed complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). It is a clinical syndrome without a pathognomonic marker.

There are three types of CRPS

Type 1—previously termed reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD)—includes the clinical manifestations of pain, functional impairment, autonomic dysfunction, and/or dystrophic changes without an identifiable nerve lesion.

Type 2—previously termed Causalgia—is defined by pain, functional impairment, autonomic dysfunction, dystrophic changes with an identifiable nerve lesion.

Type 3—are other pain dysfunction problems and are not discussed in this chapter except as part of the differential diagnosis.

CRPS types I and II may be sympathetically maintained or sympathetically independent, as defined by pain relief from a sympatholytic intervention such as intravenous phentolamine of a stellate ganglion block. Many oral medications have a sympatholytic effect.

Terminology

Nociceptive pain originates from a mechanical source. A nociceptive origin or component of CRPS is common.

Neuropathic pain emanates from an injury or malfunction of a peripheral nerve. CRPS is one manifestation of neuropathic pain. For example, pain from a neuroma or a neuroma-in-continuity that is localized to the injured nerve or phantom-limb pain is neuropathic but not CRPS.

Sympathetically maintained pain (SMP) is defined as pain, which is ameliorated by blocking sympathetic receptors. Drugs, which have this property are termed sympatholytic.

II. Complex Regional Pain syndrome

CRPS is a clinical entity defined by pain, autonomic dysfunction, trophic change, and functional impairment. There is no pathognomonic marker or test.

In the absence of pain, the process is no longer CRPS. However, residual contracture, deformity, and stiffness are considered the sequelae of CRPS.

Incidence and prevalence is

Unknown in most locals.

In Olmsted County, the incidence was reported as 5.5 per 100,000 and the prevalence as 20.7 per 100,000 in 2003.

The incidence after fracture of the distal radius varies from 4% to 39% in prospective series.

Smoking is a significant risk factor.

Synonyms—there are over 40. Some of the most common are

Algodystrophy

RSD

Causalgia

Major causalgia

Minor causalgia

Minor traumatic dystrophy

Major traumatic dystrophy

Shoulder-hand syndrome

Sympathetic-maintained pain syndrome (SMPS)

III. Anatomy and Physiology of Pain

Pain is initiated in the periphery, potentiated by local reflexes and humeral factors, relayed via peripheral nerves to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (wide dynamic range neurons), amplified and modified in the spinal cord; and transmitted to cortical centers.

Within the spinal cord, the pain signal is modified and modulated. The magnitude of pain depends upon the mechanism of initiating event; afferent information transmitted; efferent modulation; and CNS interpretation.

Painful (nociceptive) information is activated peripherally (transduction) by mechanical, thermal, chemical, or ischemic events and transmitted by small myelinated (A-D) and small unmyelinated C afferent peripheral nerve fibers to spinal cord.

The perception and physiologic consequences are related to a complex interplay of physiologic events and psychological factors.

Pathophysiology—Proposed mechanisms fall into two large groups

Peripheral abnormalities include alterations in vasomotor tone with enhanced nociceptor activity; abnormal sympathetic activity; abnormal stimulation of somatic sensory axons following partial nerve injury; increased sensory afferent impulses; local demyelination with “sprout” outgrowth resulting in increased nociceptor sensitivity; damage to peripheral nerve; damage to mixed motor/sensory nerves; peripheral microvascular shunting and secondary to abnormal sympathetic tone

Central neurologic dysfunction

These include abnormalities of the “internuncial pool”; increased activity within the substantia gelatinosa; abnormal modulation of widedynamic-range neurons; abnormal modulation of afferent signals in higher cortical centers of the brain; and/or cortical adaptations and changes.

True pathophysiology is probably a combination of peripheral and central mechanisms.

CRPS is conceptually an exaggeration or abnormal prolongation of the “normal” pathophysiologic events following injury.

IV. Natural History

Observations and prognosis

CRPS type 1 and 2 is a departure from the orderly and predictable response of an extremity to a traumatic or surgical insult. There is persistence of neuropathic pain with an inappropriate intensity combined with absence of impeding or ongoing tissue damage.

It may either represent multiple pathophysiologic subgroups or have a common etiology; however, the exact pathophysiologic cause is not defined.

A transient dystrophic response (abnormal physiology) to injury or trauma is a normal phenomenon. Abnormal prolongation of this response and inability of the patient to modulate or control the pain cycle appears to be the best explanation of RSD. A cascade of reversible and irreversible events then ensues.

The natural history is poorly defined and is altered by treatment.

CRPS is not a psychogenic condition, and the emotional suffering is the result, and not the cause of CRPS.

In general, diagnosis and initiation of treatment within 6 to 12 months of onset result in significant improvement.

However, patients with CRPS and fracture of the distal radius have a poorer prognosis; stiffness, and “poor finger function” at 3 months correlate with 10 year morbidity

Some patients in spite of early and appropriate treatment do poorly with long-term functional impairment, chronic pain, deformity, or any combination thereof.

CRPS may result in irreversible end-organ dysfunction, including loss of normal arteriovenous (AV) shunt mechanism and permanent alterations in central neurologic responses.

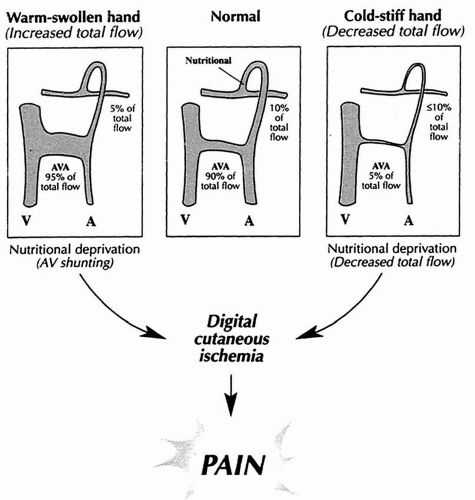

Swelling occurs early, and stiffness and atrophy are present in later stages; pain at any stage is associated with AV shunting and nutritional deprivation (relative ischemia).

Eighty percent of those treated within 1 year of injury show subjective improvement; only 50% of those treated after one year improve.

The most effective aspect of treatment of RSD is early recognition—best results occur if diagnosis and active management are initiated before 6 months.

Clinical characteristics

Pain is unremitting, “out of proportion to the injury” and does not depend on the magnitude of the inciting effect; often described as “tearing”, “burning”. Some CRPS patients may fearfully withdraw the limb from the examiner and develop avoidance patterns. Pain on exposure to cold is frequent. Pain is not significantly improved with the use of narcotic analgesics, but it will frequently respond to sympatholytic medications. Difficulty sleeping, restlessness, and anxiety are common complaints. Pain may be assessed using standardized and/or validated instruments (e.g., visual analog scale, Short-Form 36, self-administered questionnaires). Cold sensitivity may be assessed using the McCabe scale.

Pain includes

Allodynia (painful response to a nonpainful stimulus)

Hyperpathia (increased pain sensitivity)

Hyperalgesia

Stiffness of fingers, wrist, and shoulder is common.

Functional deficit is secondary to pain swelling and stiffness.

Trophic changes (autonomic dysfunction) include sudomotor dysfunction, temperature, swelling, diffuse osteopenia, and skin alterations.

V. Diagnosis/Clinical Presentation

Extremely variable in history, physical findings, and diagnostic workup.

History almost always includes surgical or traumatic insult; however, it may have been very mild.

Clinical diagnosis is made if pain is intense or unduly prolonged; and two or more of the following are noted: Stiffness; delayed functional recovery; trophic changes and/or autonomic dysfunction.

Autonomic dysfunction is almost always present in some form and includes vasomotor instability; pseudomotor abnormality; thermoregulatory changes; and abnormal nutritional flow with aberrant AV shunting.

Presentation—usually presents after trauma—major or trivial. Women are more frequently affected than men. Children and adolescents are afflicted rarely but can have severe involvement. Upper and lower extremity involvement is approximately equal. An identifiable mechanical trigger or etiologic component (e.g., entrapped nerve) is present in less than 50% of cases.

Signs and symptoms are pain; swelling; stiffness; dry skin; hair loss; abnormal sweating; and /or discoloration.

Diagnostic tests

Plain x-rays may be normal but often show osteoporosis with subchondral resorption. Classic CRPS roentgenograms demonstrate osteopenia with periarticular and subchondral resorption (Sudeck atrophy), but changes appear late and therefore radiographs are not a useful screening tool. As many as 30% of patients have no x-ray abnormalities.

Bone scans may be characteristic and confirmatory for CRPS, but are not pathognomonic. Three phase scans are utilized but are insufficiently sensitive. First and second phase bone scans may demonstrate asymmetry of flow dynamics and quantify vasomotor instability and abnormal autonomic flow. Third phase scans—when positive—demonstrate increased periarticular uptakes in involved and uninvolved joints.

A positive third phase bone scan adds credence to the clinical diagnosis; identifies a recognizable subgroup of CRPS; has no prognostic significance; and does not correlate with thermoregulatory or vasomotor states.

Kozin

MacKinnon

Werner

Specificity

75%-85%

96%

92%

Sensitivity

<60%

98%

50%

Thermoregulatory and nutritional blood flow testing help to quantitate and quantify distal extremity autonomic function as reflected in thermoregulatory and nutritional blood. A form of stress—thermal or emotional— improves reliability and reproducibility (Fig. 9.1).

Isolated cold stress test has been described to assess dynamic sympathetic response of an extremity to changes in environmental temperature.

It permits the measurement of skin surface temperature of the digit, which is a reflection of total blood flow. It is highly sensitive to vasomotor disturbances that occur in 80% to 90% of patients with RSD. It is not specific for CRPS.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access