Chin

BIOANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

The chin is a protrusion of soft tissue overlying the distal point of the mandible. Superiorly, it is bordered by the mental crease, and inferiorly, it merges into the neck. Laterally, the chin merges into the jawline.

The soft tissues of the skin are supplied mainly by anastomosing vessels branching from the facial artery as it deflects superiorly and lateral to the oral commissure. Sensory innervation derives from the mental nerves and motor innervation is provided by the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. In most cases, a larger caliber vessel is identified running horizontally at the junction of the mentalis with the orbicularis oris. The mental nerve ascends deep to the musculature to innervate the lip.

The contour of the chin varies substantially from one individual to another. In youth, the mental crease is often minimal, and a defined, sharp arciform mental crease is more common with age and sun exposure. The soft tissue of the chin may be clefted or rounded.

The chin is a soft dome of tissue. The dermis may be either thin or elastotic and cobblestoned. The underlying adipose is more fibrous than in other areas of the face as septae connect the underlying mentalis to the overlying dermis. There is not a clear plane on the chin between the adipose and the mentalis, as the two merge together.

Mobility on the chin is found in two planes. First, even though the adipose and mentalis intermingle, a plane can be created over the surface of the mentalis. This provides substantial motion and also prevents scar inversion in suturing smaller and moderate wounds. For closure of extensive defects, the mentalis may actually be separated from its insertion onto the mandible.

RECONSTRUCTIVE OPTIONS

Linear Repairs

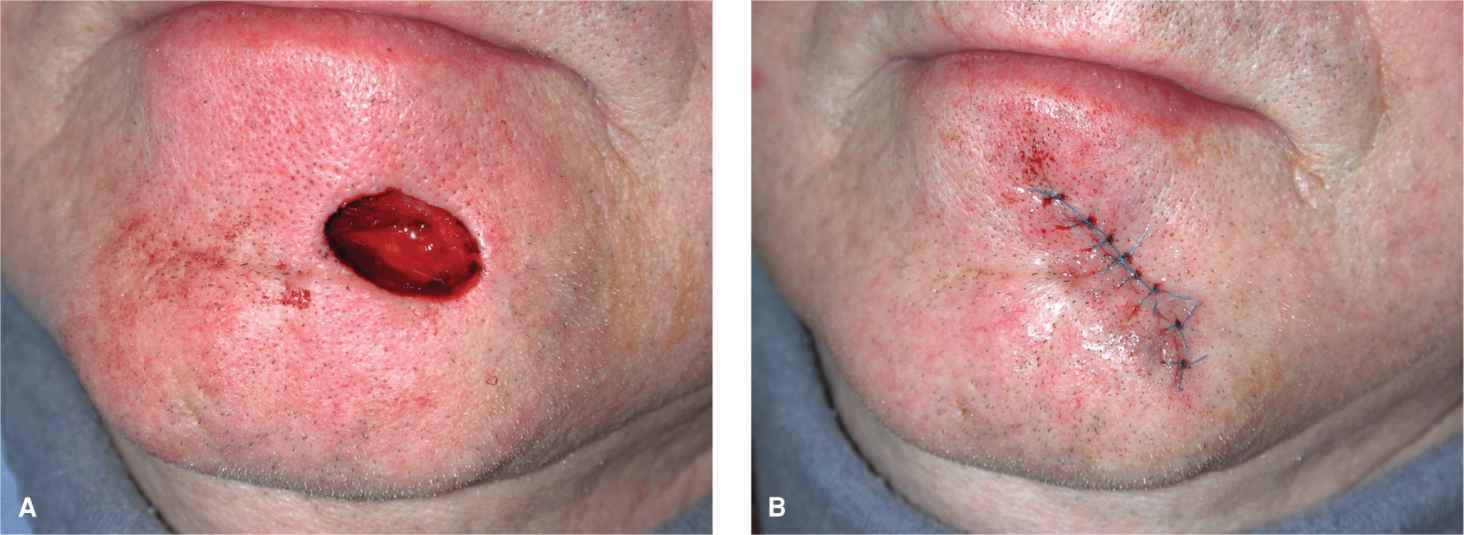

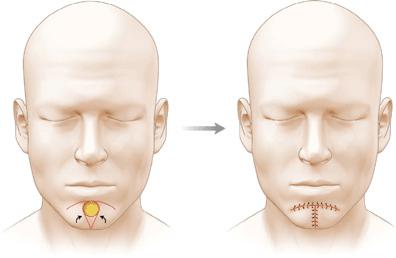

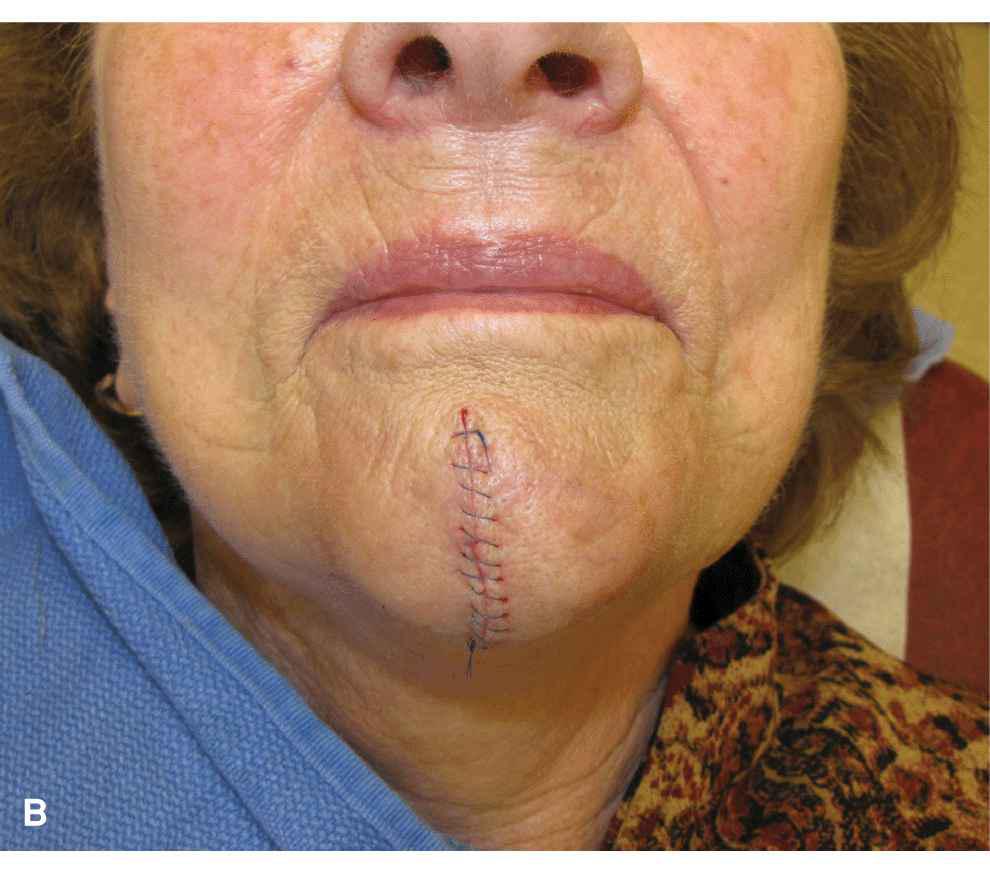

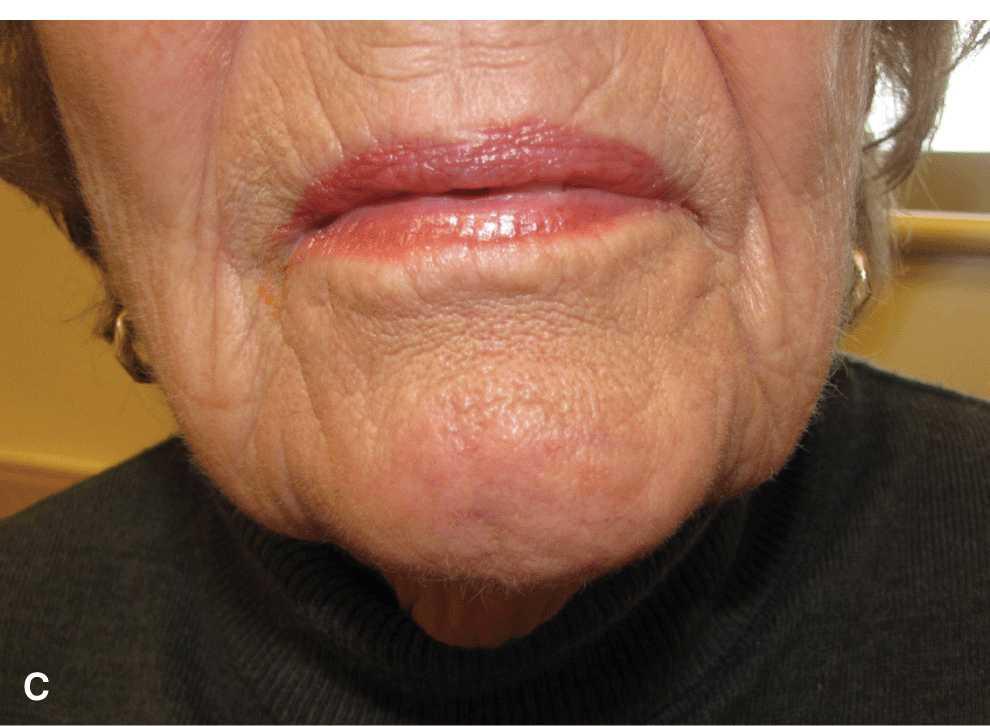

Small-to-moderate wounds on the chin are amenable to vertical linear closure. Because of the prominent convexity of the chin as it passes over the mandible, linear repairs often need to be longer than would be needed to avoid standing tissue cones on a flat surface. A consequence of performing a linear repair on the chin can be an elevation of the margin of the lip as the chin bows upward at closure. Similarly, if the repair is not carried over the margin of the chin, a standing tissue cone may develop which projects from the jaw (Fig. 15.1). In patients with a prominent mental crease, a vertical repair that bridges the chin and lower lip should generally be avoided. A way to mitigate the impact of crossing the crease is to perform the repair as an S-plasty (Fig. 15.2).

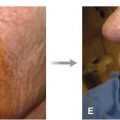

Figure 15.1 Linear repair on the chin. (A) Operative wound on the lower chin. (B) Linear repair coursed over the jawline to avoid a pucker. (C) Repair at 6 months

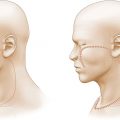

Figure 15.2 Curvilinear closure on the upper chin. (A) Operative wound bridges the chin and lower lip. (B) An S-shaped closure aids in crossing the mental crease without bridging

Linear closures on the chin should be performed just above musculature, and substantial undermining is indicated to prevent scar inversion. A repair that closes easily on the chin may still invert and create an unaesthetic scar unless the edges of the wound are suitably undermined and the edges are sutured with adequate eversion. Even when appropriately performed, linear repairs on the chin may produce a visible scar, more so than for similar repairs elsewhere on the face. While the repairs are often under little to no tension, the scar line may be prone to inversion.

Advancement and Rotation Flaps

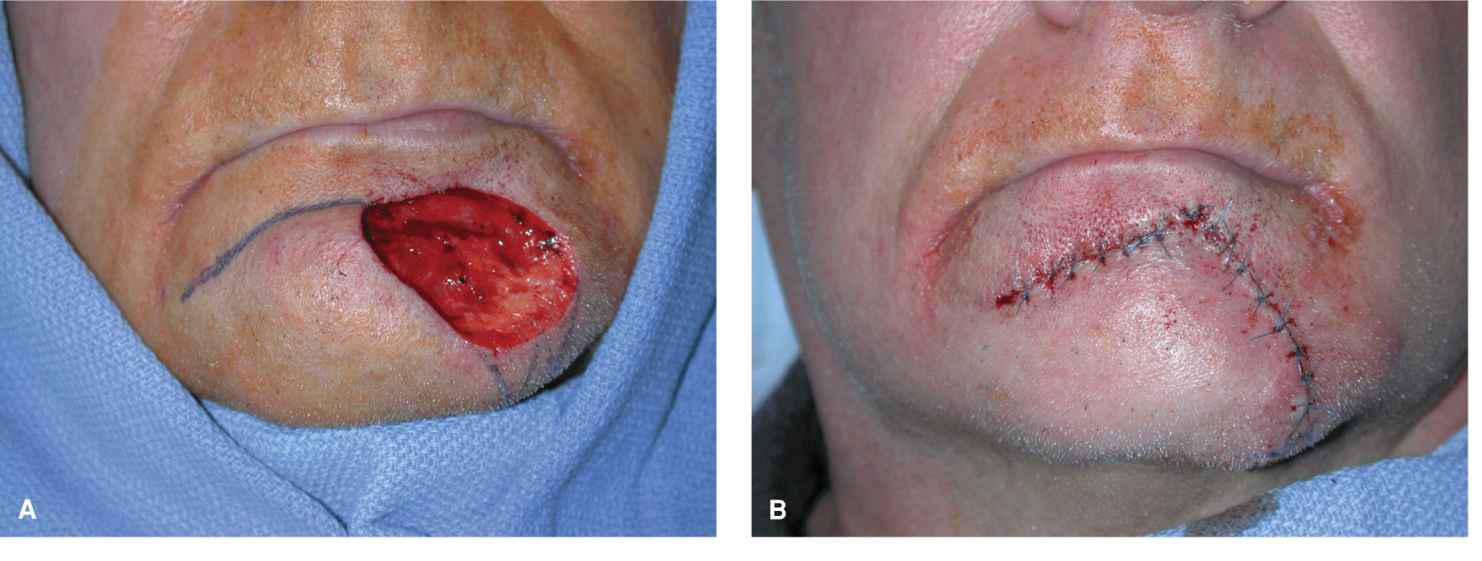

Flaps on the chin often combine components of rotation and advancement. For central defects overlying the mental protuberance, a suitable reconstruction is a bilateral rotation flap in which the standing tissue cone is removed inferlorly and the arcs of the bilateral advancement curve along the mental crease outward and inferiorly. This amounts to an A-T advancement with a component of rotation and a curved superior border conforming to the mental crease (Fig. 15.3).1 This repair is often utilized even if the wound could be closed linearly in order to avoid crossing the mental crease.

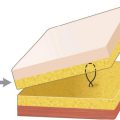

Figure 15.3 Bilateral rotation flap for closure on the chin

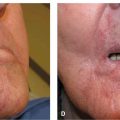

Moderate-to-large wounds of the mid-to-lateral chin are readily repaired with unilateral rotation flaps that curve along the mental crease all the way to the contralateral junction of the cheek and chin (Fig. 15.4).2 Because these tend to be longer rotation flaps, it is often feasible to sew out any length mismatches along the secondary wound and a backcut or removal of a standing tissue cone is often unnecessary. The arc of the flap should curve all the way along the mental crease and the secondary defect usually closes without placing tension on the lower lip. Modest superolateral wounds can be repaired with combined rotation and advancement from the lateral chin. A standing tissue cone is dropped inferiorly from the operative wound and a curvilinear incision is incised toward the oral commissure. The flap then advances and rotates into place (Fig. 15.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree