CHAPTER 17 Male Rhinoplasty

Summary

With the ever-increasing trend in male plastic surgery, proficiency in male rhinoplasty techniques continues to be essential. This chapter should provide the basic techniques and a guide to understanding and performing the male rhinoplasty.

Introduction

Reconstructive rhinoplasty dates back millennia to ancient Egypt. 1 Ancient papyrus translated by modern Egyptologists has shown that the Egyptians used nasal disfigurement as a means of punishment and with this came the need for reconstructive surgery. Interestingly enough, this was not limited to just the Nile River Valley. Throughout the ancient world, nasal disfigurement and its subsequent repairs have been described ranging from Mesopotamia to India. 2 , 3 The repairs often used local tissue versus pedicle flap techniques to help reconstruct the soft-tissue defects. Over the next several thousand years, multiple surgeons developed their own techniques of nasal reconstruction but progress was overall slow compared to modern growth. It is impressive, however, that this was all done before antiseptic techniques and without the advent of anesthesia. The modern history of rhinoplasty dates back to the early 19th century with Carl Ferdinand von Graefe’s publication of the book Rhinoplastik in 1818 detailing various reconstructive techniques. Over the next 100 years, advances in rhinoplasty, especially for cosmetic purposes, came from Dieffenbach, Roe, Weir, and ultimately a young physician named Jacob Lewin Joseph, also known as Jacques Joseph. 1 Joseph himself put on workshops where he would directly and indirectly end up teaching the likes of Gustave Aufrecht, John M. Converse, Irving Goldman, and Maurice Cottle. 1

Rhinoplasty as a procedure can base its roots on generations of surgical knowledge being passed down and, in the past 40 years, has truly blossomed into what is in practice today. The publication of Open Structure Rhinoplasty by Calvin Johnson and Dean Toriumi heralded in the era of the open approach. 4 Current rhinoplasty practices include both the endonasal and open approaches with surgeon preference and patient selection guiding the decision.

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons releases data annually detailing the number of cosmetic procedures performed. In 2015, the most commonly performed surgical procedure in males was rhinoplasty with approximately 50,000 procedures performed. 5 The rhinoplasty numbers actually beat out the next most common procedure by a factor of two to one. Overall, one in four rhinoplasties performed were performed on males, which brings us to the heart of this chapter. Understanding the essential differences between male and female patients is critical to obtaining excellent patient results and building a thriving practice ( Table 17.1 ).

Anatomy

The expert surgeon must thoroughly understand the inherent differences between the male and female nose as it pertains to the aesthetic surface and underlying structural anatomy.

Aesthetic Anatomy

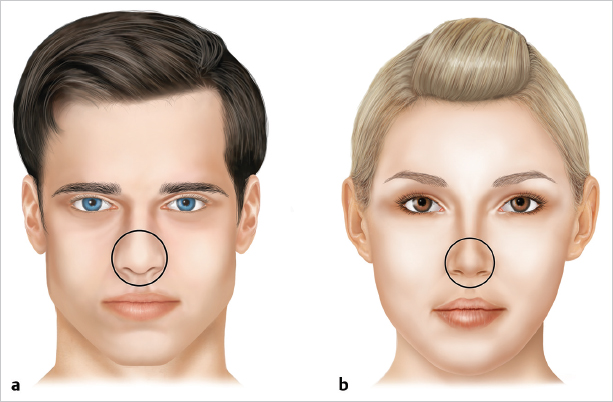

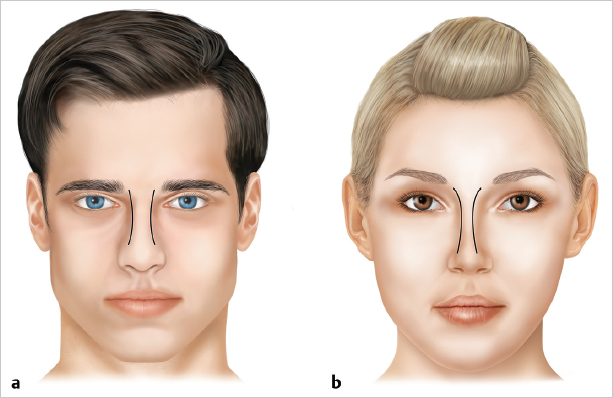

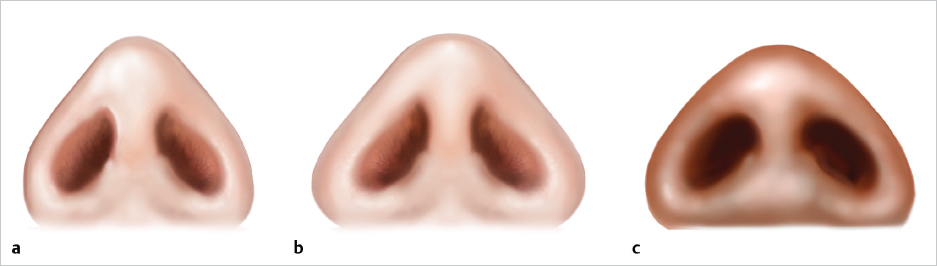

In general, the male face is less rounded with overall larger and more accentuated and sharper features. Starting with the frontal view ( Fig. 17.1 ), it is important to note that the male nose is often wider along all three thirds and has a less curvilinear brow tip aesthetic line ( Fig. 17.2 ). The rhinion often has a lateral protuberance visually separating the upper and middle third. The bony upper third is often more convex, although this may be requested to be made straight and the facial plane bony insertion is wider. The tip is often larger and less defined reflecting larger and thicker lateral crurae with a more obtuse interdomal and intradomal angle with more prominent sebaceous glands, and the soft-tissue envelope as a whole is often thicker ( Fig. 17.3 ).

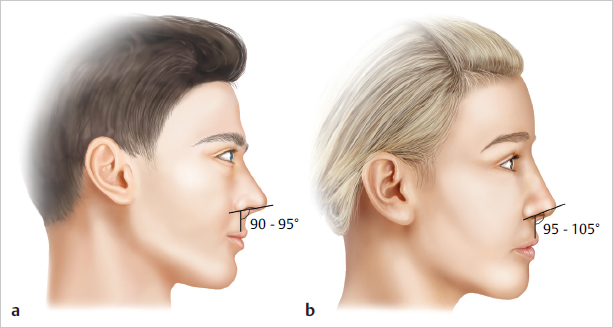

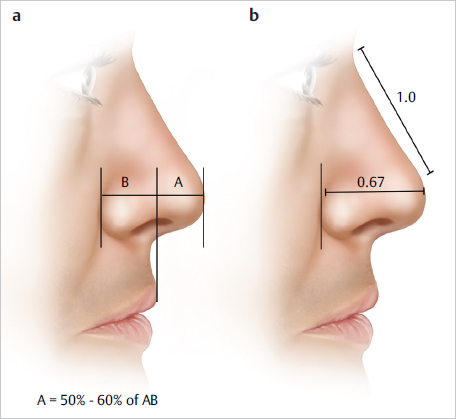

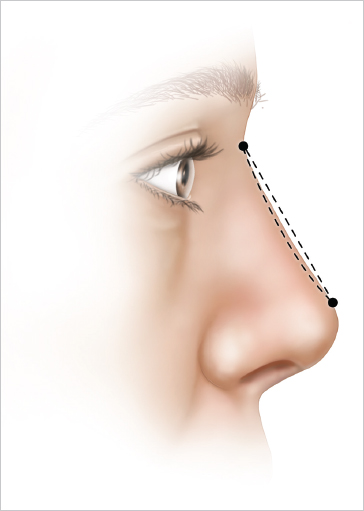

On the lateral view ( Fig. 17.4 ), we note that the male nose’s dorsal profile often has a rhinion hump, although most men seeking a rhinoplasty often prefer to have the hump removed creating a straight though not concave bridge. The radix is often more superiorly based with a more anterior-based position as well. This goes hand in hand with the male dorsum being higher, giving the perception of a longer and larger nose. The tip is often further projected with less rotation, approximately 90° to 95° compared to the female nose’s rotation, which ideally is between 95° to 100° ( Fig. 17.5 , Fig. 17.6 ). The ideal chin position for a man should lie no further posterior than a line drawn through the most projecting portion of the upper lip that is perpendicular to a line drawn along the Frankfort plane.

Avoiding feminization in male patients is of the utmost importance. The most commonly made mistakes are as follows:

An overresection of the nasal dorsum giving the lateral profile a concave appearance ( Fig. 17.7 ).

An overly rotated tip.

An overly sculpted tip.

These three changes, which are commonly preferred in female rhinoplasty, will feminize the male and lead to unhappy patients.

Structural Anatomy

The bony component of the male nose is as varied in length and shape as a female’s with one major exception: The male bony vault is typically much thicker and requires more force to fracture and often requires medial as well as lateral osteotomies to reposition the bones. The thin bones of the female nose can often be repositioned with lateral osteotomies alone, particularly if medial osteotomies will splinter the dorsum. A small dorsal hump in men can often be reduced with rasping alone without concern of creating an open roof deformity because of their thicker nasal bones.

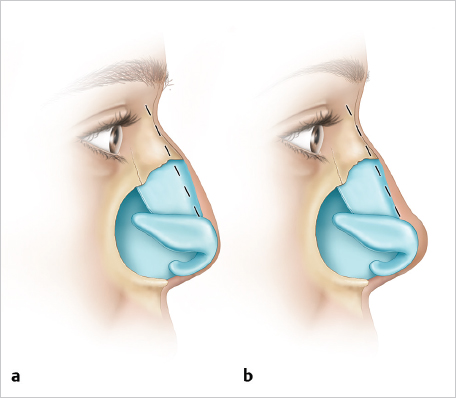

Similarly, the nasal middle third’s upper lateral cartilages (ULCs) are thicker, which allow removal of small cartilaginous humps without disarticulation of the ULCs from the dorsum. However, if the horizontal component of the middle third is removed, much larger spreader grafts are required to maintain a masculine middle third.

The lower third alar cartilages are both thicker and larger than a female’s. The interdomal and intradomal angles are larger, and the domes themselves are less defined. The skin of the lower third is thicker due both to a thicker dermis and abundant subcutaneous tissue as well as the presence of more sebaceous glands.

Patient Selection

Not unlike their female counterparts, patient selection is crucial when it comes to elective operative intervention. A surgeon should proceed with performing an aesthetic operation only if the patient has demonstrated sufficient satisfaction of the intended end result clearly conveyed by the surgeon using virtual surgery morphing techniques. Thus, it is incumbent upon the surgeon to demonstrate a realistically achievable result in their morphing exercises. Any hesitancy, uncertainty, or unenthusiastic reaction to the morphed image is a red flag that the patient will not be happy postoperatively and the surgery should not proceed. In the senior author’s experience (P.J.M.), the vast majority of patients know what they do not like about their nose and know what they want it to look like or are extremely satisfied with a computer-morphed result that is shown. These patients are excellent candidates for rhinoplasty. Be extremely cautious proceeding with those that express repeated dissatisfaction, disappointment, or unenthusiastic responses with every reasonable option discussed or morphed image created. Those who cannot be satisfied preoperatively are sure to be dissatisfied postoperatively. Male patients often can be nonspecific about their initial desires. It is the surgeon’s goal to elicit the patient desires and to help educate the patient regarding appropriate expectations. Regarding male rhinoplasty, there is one specific patient subset that the surgeon should be leery about operating on and this is the “SIMON” (Single, Immature, Male, overexpectant, Narcissistic) patient. Historically, this subset of male patients tends to have unrealistic expectations and may be unhappy with objectively positive outcomes.

It is worth a brief digression at this point to discuss the best technique for turning down a patient’s request to have surgery. Ultimately, if one concludes that the patient has unrealistic expectations or cannot be satisfied, then a reliable technique to withdraw your services is to be honest while not insulting the patient. Sincerely inform him that you know you cannot meet his expectations and that you are not the right surgeon for him. Do not be surprised if he persists and in so doing compliments you and showers you with praise on your achievements and pleads that you are the only one left to solve his problem. In the senior author’s experience, those maneuvers are only more red flags. Be polite. Be persistent and be reassured you are making the right choice for the patient and for yourself.

The more commonly seen reasons for male patients to desire a rhinoplasty include the dorsal hump, ptotic tip, poor lower third definition, and the large nose. These patients often have clear complaints and these cosmetic complaints often can be rather reliably treated.

Ethnic male rhinoplasty is a subcategory within male rhinoplasty, which cannot be overlooked. The Mestizo and African nose often has a thicker soft-tissue envelope and weaker lower lateral cartilage with more cephalic-orientated lower laterals than the Caucasian nose ( Fig. 17.8 ). This is something that must be thoroughly considered, as the angularity and definition that are often achieved during Caucasian rhinoplasty would be significantly harder to achieve. We also note that the ethnic nose often has significantly less caudal cartilage, and we employ various septal extension techniques often to achieve adequate projection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree