CHAPTER 13 Chin Augmentation: Expert Technique

Summary

This chapter is based on years of mentorship from expert teachers as well as my own study of the face. An attractive chin has the right combination of size, shape, and contour. Improving the appearance of a chin can be achieved by any combination of bony osteotomies, alloplastic augmentation, skin resurfacing or redraping, and/or soft-tissue fill. Because soft-tissue operations of the face are described elsewhere in this text and orthognathic movements of the mandible are beyond the scope of this chapter, I focus on more conventional genioplasty techniques. Because chin surgery complements other procedures, chin aesthetics should be evaluated in relation to the appearance and proportions of the face. Rather than memorizing numerical standards, a systematic nose-to-chin assessment should include the nose, midface, lips, maxillomandibular dental relationship, chin pad thickness, labiomental fold depth and height, static chin pad position, and dynamic chin pad motion with smile. Whether you are dealing with a complex multidimensional soft and hard tissue chin deformity or a simple sagittal chin deficiency, an emphasis should be placed on facial balance. Fortunately, the majority of men seeking consultation will have a mild sagittal deficiency. This one-dimensional problem naturally lends itself to alloplastic augmentation. That said, the role of osseous genioplasty should not be overlooked. Importantly, when making a treatment plan, your assessment better be right on, or the simple chin augmentation will deliver simply dreadful results.

Introduction

In The Descent of Man, Darwin 1 considers whether man is descended from some preexisting form, the manner of his development, and the value of the difference between the races of men. In his satire, Descent of Man, T.C. Boyle blurs the boundary between the rational human and the irrational animal world featuring such absurd situations as the canine film star Lassie leaving her master Timmy for a love affair with a coyote and a woman falling in love with a brilliant chimpanzee who is translating Darwin into Yerkish. Boyle’s writing highlights the incongruity between nature’s parsimony and vanity. Take the chin for example—nearly useless from a mechanical standpoint and without a phylogenetic precursor, the chin juts out prominently on the face of human physiognomy. Yet, it was not until we had our chins that we set about assigning value to them—strong, weak, angular, square, narrow, protruding, long, round, or dimpled, depending on your tastes. And accordingly, those tastes, as well as the sexual selection that arise from them, ensure that our chins remain a part of us. It might be biomechanically useless, but you would look like a silly Sidney Smith character without one.

Physical Evaluation

The chin should be evaluated in relation to the appearance and proportions of the face. Emphasis is placed on facial balance rather than anthropometric standards. Whether dealing with a complex multidimensional soft and hard tissue chin deformity or a routine sagittal chin deficiency, I use a systematic assessment, which includes the following:

Nose.

Midface.

Lips.

Maxillomandibular relationship.

Chin pad thickness.

Labiomental fold depth and height.

Static chin pad position.

Dynamic chin pad activity.

Submental contour.

The aesthetic goals, as well as any previous surgical or orthodontic interventions are noted. The face is observed and photographed in repose and smiling from both the front and profile views. Mandibular and/or mentum deficiency, excess, or asymmetry is documented. Below are some of the highlights of this assessment.

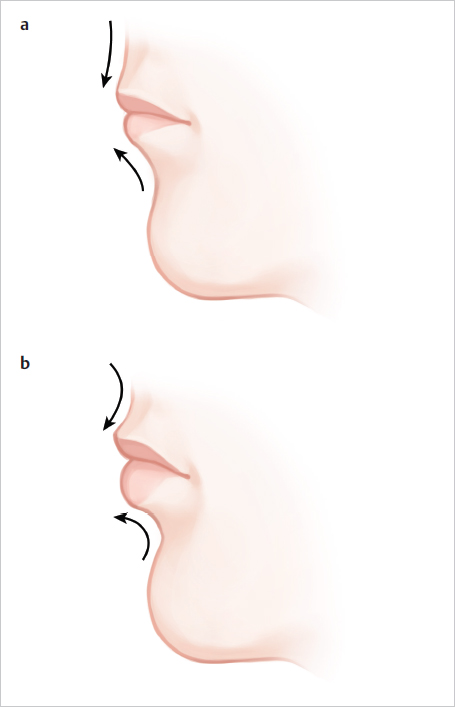

Lower Lip Analysis

The inclination of the lower lip from the white roll to the labiomental fold affects the perception of chin size ( Fig. 13.1 ). If the inclination of the lower lip is vertical and the demarcation between the lip and chin is poor, the patient will appear to have a larger chin than expected after augmentation. This is particularly true if a full height implant is used. The lower lip analysis is intermingled with the labiomental fold analysis because the lip inclination helps define the labiomental fold. If a patient has a deep overbite and the lip is everted, then the lower lip will have an oblique inclination. The obliquity of the lower lip will contribute to a deeper labiomental fold with a more acute angle. The surgeon should note this, because an alloplastic implant or genial segment that is too tall will deepen the fold and make the labiomental fold angle even more acute.

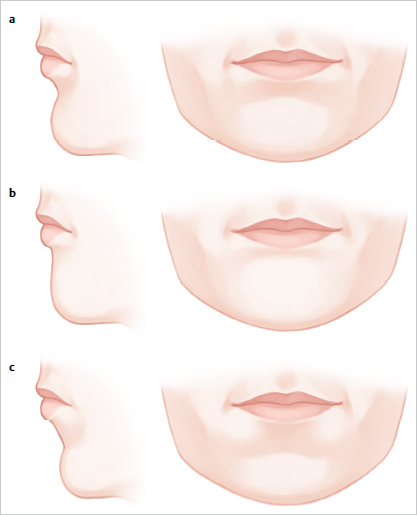

Labiomental Fold Analysis

If two chins project exactly the same amount, the chin with the higher and/or shallower labiomental fold will always appear larger from the front ( Fig. 13.2 ). Because the chin is primarily seen as the pad, the labiomental fold defines the vertical height of the chin. Thus, augmenting a patient with a high, shallow labiomental fold tends to increase the appearance of the vertical height of the chin as well as its overall size. To overcome this problem, the surgeon should reduce the vertical height of the implant or genial segment to limit augmentation to the pogonion. If the chin is long with a high fold, the patient may need both a vertical chin reduction and a sagittal augmentation. In contrast, a patient with a low, distinct labiomental fold will tolerate chin augmentation much better because the implant or genial segment accentuates only the chin pad.

Static and Dynamic Chin Pad Analysis

The chin pad thickness can be easily estimated by palpation (normal thickness: ~8–11 mm). Soft-tissue chin projection should be greatest at the inferior edge of the pogonion. The soft-tissue chin pad position, static ptosis, clefting, and fasciculations are noted. Chin pad fasciculations are usually a result of mentalis strain to obtain lip seal. Because the chin pad is dynamic, the soft tissues are also assessed during animation. The observer will note that when a chin pad is thick, a smile usually improves the patient’s appearance because the thick pad becomes effaced. In contrast, as a thin chin pad is effaced during a smile, it appears even more prominent. In a normal smile, the zygomaticus and levator muscles elevate the oral commissures pulling the chin pad superiorly. Some patients have a horizontal nonlifting smile (risorius dominated) such that the lower lip depressors are unopposed; this results in dynamic chin pad ptosis with smiling.

Bony Chin Analysis

The optimal site for bony chin projection is the pogonion, not the inferior edge of the labiomental fold. Because the surgical spine of the mental symphysis is beneath the labiomental fold, it may contribute to an acute labiomental fold or chin projection that is too superior and, therefore, need reduction. The location and prominence of the surgical spine is determined to be palpation. In other cases, mentalis muscle coalescence beneath the fold (usually with a soft-tissue cleft) can contribute to excessive lower labiomental fold prominence. This can be differentiated from bony chin excess by asking the patient to pout.

Submental Analysis

Subcutaneous adipose and skin laxity are assessed. The surgeon should determine whether pre- or subplatysmal adipose is contributing to submental fullness. Skin and pre- or subplatysmal adipose may need to be excised to improve the chin or neck contour, or a neck lift may be indicated.

Anatomy

An understanding of the anatomy enhances a surgeon’s evaluation of the chin. On the labial surface of the mandible in the midline is the symphyseal spine, which is also referred to as the surgical spine. The symphyseal spine divides to enclose a triangular eminence called the mental protuberance. The center of the mental protuberance is depressed, but its raised lateral borders form the mental tubercles. On either side of the upper symphysis, just below the mandibular incisors, are the incisive fossae. The incisive fossae are the origins of the mentalis muscle. The mentalis muscles coalesce to form the bulk of the chin pad, and they insert into the chin pad dermis to maintain lip position in repose and elevate and protrude the lower lip in animation. The mentalis muscles have horizontal and oblique components. The upper horizontal portion, which originates just below the attached gingiva, is responsible for the lip level and position in repose. The function of the horizontal portion of the mentalis muscle, in isolation or in conjunction with the orbicularis oris, determines the shape and position of the labiomental fold as well as the lower lip position. The oblique portion of the mentalis muscles may fuse centrally (as in most cases) or remain separate superiorly or inferiorly to form a cleft. Thus, a cleft in the chin is, in essence, a muscle-deficient zone. The oblique portion of the mentalis muscles pulls the chin pad against the mandible, drawing the lip upward and allowing us to pout. Finally, the oblique fibers also elevate the central portion of the lip. Lateral to the mentalis muscle, beneath the second premolar, midway between the superior and inferior borders of the body are the mental foramina. In a vertically short mandible, the foramina may be higher than expected.

The lingual surface of the mandible has a midline median furrow. Inferior to the median furrow are the bilateral parasymphyseal mental spines. The mental spines are the origins for the genioglossus muscles. Immediately inferior to the mental spines is a median impression that is the origin of the geniohyoid. Also, inferior and lateral to the mental spines are oval depressions for the attachment of the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles. Running distal and superior from either side of the lower part of the symphysis are the mylohyoid lines, which give origin to the mylohyoid muscles bilaterally.

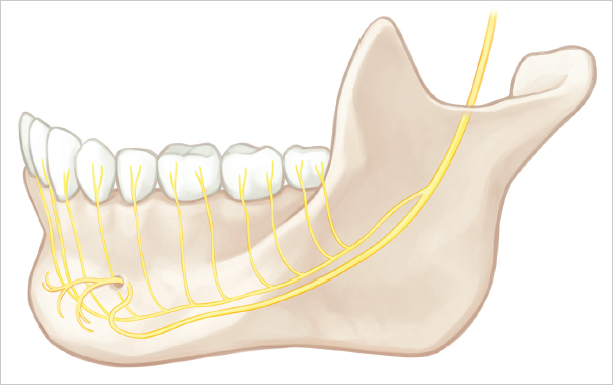

Sensory innervation of the chin is provided by the mental nerves. The mental nerve is a branch of the third division of the trigeminal nerve that exits the skull base through the foramen ovale and gives off nine branches including the inferior alveolar nerve. At the lateral pterygoid, the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle passes between the sphenomandibular ligament and the ramus and enters the mandibular foramen on the medial surface of the ramus. The mandibular foramen is usually located about 2 cm from the anterior border of the ramus and nearly opposite the antilingula (on the buccal surface of the mandible). The inferior alveolar nerve is a sensory nerve, but a few motor and sensory fibers from the mylohyoid nerve run alongside. The inferior alveolar nerve usually travels in a single canal (2–2.4 mm in diameter) to supply the mandibular molars, premolars, and gingiva. The terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve passes as much as 4.5 mm below and 5 mm mesial to the mental foramen before looping up to emerge as the mental nerve ( Fig. 13.3 ). The mental nerve innervates all of the skin of the chin (except for quarter size patches of skin on either side of the chin pad), the lower lip, the lower lip mucosa, the gingiva, the incisors, and the canines. A sensory branch of the mylohyoid nerve supplies the quarter size patches of skin on either side of the chin pad. All muscles of facial expression around the chin are innervated by branches of the facial nerve except for the mylohyoids and anterior bellies of the digastric, which are innervated by the third division of the trigeminal nerve.

Patient Selection

Ultimately, the size and shape of the chin is affected by the soft tissues draped over the surface of the mandible. A vertical lower lip gives the appearance of a tall chin, while an oblique lower lip gives greater demarcation between the lip and chin resulting in a more defined smaller chin pad. The labiomental sulcus is the dividing line between the lower lip and the superior part of the chin pad. The vertical location and depth of this fold affects the perception of chin size. For example, a high, shallow labiomental fold gives the illusion of a vertically long chin ( Fig. 13.2 ). In contrast, a lower, more defined labiomental fold gives the appearance of a smaller chin ( Fig. 13.2 ).

The majority of men seeking consultation for the treatment of a chin deformity suffer from only a mild sagittal deficiency. This one-dimensional chin deficiency naturally lends itself to alloplastic augmentation or a genial advancement. However, unless the surgeon takes all of the above factors into consideration, a simple chin augmentation may not deliver expected results. For example, surgeons continue to identify the sagittally deficient chin but overlook the inclination of the lower lip and the height of the labiomental fold; this oversight leads to unanticipated outcomes. In sum, when making a treatment plan, your assessment must be right on, or the simple chin augmentation will deliver simply dreadful results.

To sagittally augment a small chin, I typically use an implant, but an osseous genioplasty will work just as well. I tend to choose textured implants over silicone when operating on men, performing revision chin surgery, and when treating the tension chin. A silicone implant can be used in the same way as a textured implant, but it is harder to securely fix to the mandible. Moreover, a capsule tends to form around the silicone elastomer, which may lead to more difficulties if the chin implants were ever revised. Implants are so convenient that I tend to reserve osseous genioplasties for more complex cases. Because an osseous genial segment has six degrees of freedom, it is often a better treatment option for an asymmetric chin or a long nonprojecting chin or when combined with an orthognathic procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree