CHAPTER 12 Chin Augmentation

Summary

This chapter provides the surgeon the essential knowledge needed to evaluate and effectively treat patients who may be candidates for chin augmentation. We have provided a directed way to evaluate the patient with a breakdown of appropriate anatomical descriptions. Later in the chapter, we have a step-by-step operative guide with pearls and pitfalls included for chin augmentation.

Introduction

Chin augmentation has been a tool used by plastic surgeons over the past 100 years. The use of osteoplastictechniques to help augment the chin had been the gold standard in the past. Aufricht 1 in the 1920s published his series of combined rhinoplasty and chin augmentations with the use of bone from the nasal hump. At approximately the same time, various implants were being used, including ivory, metal, and various primitive plastics. Joseph Safian, 2 who learned the techniques from Jacques Joseph, was a prominent believer in the use of ivory for chin implants with remarkably low infection rates. In 1948, the Dow Corning Corporation developed a medical grade silicone product with the trademark name Silastic. Silastic implants have the major benefit of being biologically inert, easily modified, flexible, and firm. 2 Over the past 50 years, various alloplastic materials have been developed, including methyl methacrylate, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, and porous high-density polyethylene implants. We prefer the use of Silastic implants because of their inherent benefits and long track record and ease of removal when indicated.

The oral maxillofacial literature is ripe with techniques for osseous genioplasty for chin augmentation. These methods are appropriate in patients desiring both vertical and horizontal augmentation unachievable with chin augmentation, but the increased morbidity of swelling, asymmetries, malunion, and larger incisions limits the indication for this technique in our patients, who prefer a balance between minimal morbidity with maximal outcomes. We have found that Silastic implants work exceptionally well to project in the anterior–posterior direction, and certain models can slightly improve the vertical component.

Physical Evaluation

Assess chin or nose projection in the Frankfurt plane.

Assess presence of a cleft.

Assess the superior inferior projection as well as anterior posterior.

Anatomy

An underprojected chin often augments the appearance of the other facial units. This stems from the fact that balance is key to facial aesthetics. The balance between the facial thirds often is something overlooked by patients and relies on the experienced surgeon to guide them. Classically, this is noted in the rhinoplasty patient whose nose appears significantly too large for the face, while in reality, it may be that the chin is too weak to balance the nose.

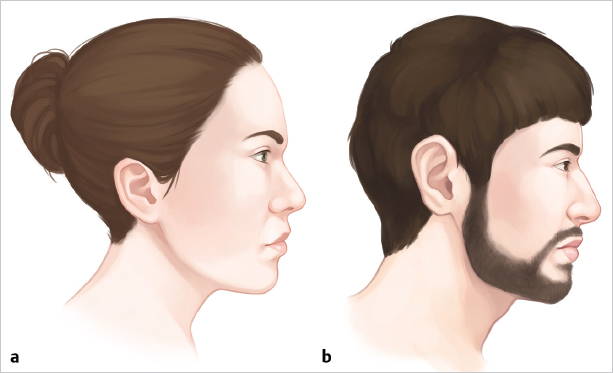

In the lateral view, with the male patient’s head oriented in the horizontal Frankfurt line, we expect a vertical line dropped off the lower lip to be at least at the level of the chin ( Fig. 12.1 ). For an individual with an exceptionally strong jawline, the chin may be several millimeters in front of this line. This is in contrast to a female’s chin that would be aesthetically pleasing at approximately 2 mm posterior to this line1 ( Table 12.1 ).

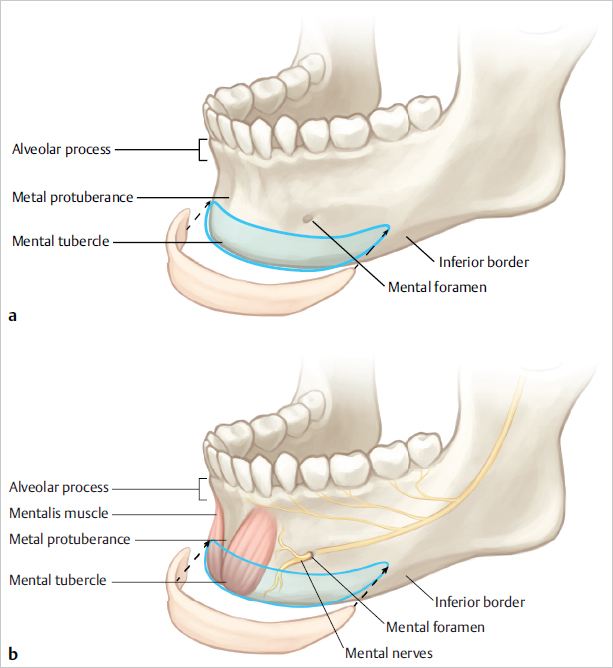

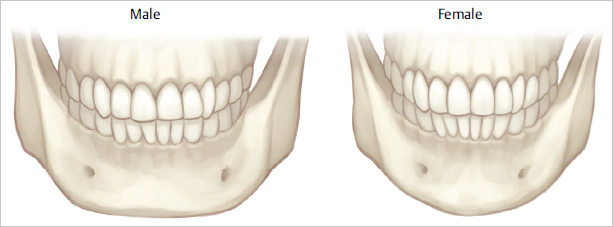

The midline lower face is a rather safe operative field. Below the skin or subcutaneous tissue, we find the mentalis muscle followed by the periosteum and the anterior mandible itself ( Fig. 12.2 ). The terminal branches of the mandibular nerve (V3) exit the mandible at a vertical line down from the midpupillary line. Intraorally, the nerve can be identified between the mandibular canine and the first premolar. We prefer the external approach for placement of our implants and find that the submental crease often hides the incision well. 1 It’s important to also note that the female chin comes more to a point, while the male chin often has a squared anterior appearance ( Fig. 12.3 ).

Patient Selection

Proper patient selection yields excellent results along with happy patients. Our preferred techniques for chin implant placement rely on patients needing mostly increased projection in the anterior–posterior direction. If a patient were exceptionally deficient in the superior–inferior direction, osseous genioplasty techniques would yield a superior result. We also find that the patient, who is unsure whether he or she would like an implant, can either receive injection of saline that gives an immediate but shortlived imilarity of an implant, or may benefit from an injection of filler for a longer trial period. This in-office procedure can be combined with other injection techniques to help define the entire jawline not just the anterior mandible.

Regarding patients with an overprojected mandible, we have had success in reduction of chin augmentations. With the use of diamond burrs, we are able to shape the anterior mandible with a modest reduction in both anterior–posterior and superior– inferior directions if needed. It is important to note that any patient with significant malocclusion would probably be better served by other techniques to address both their orthodontic concerns as well as cosmetic appearance.

Steps for Chin Augmentation

Chin Implant Placement

If the procedure is to be performed in conjunction with a rhinoplasty, we prefer to perform the implant first. The submental crease is identified, and an approximately 1.5-cm midline marking is performed. Subsequently, approximately 2 to 3 cc of local anesthesia with epinephrine is injected along the anterior mandible with special attention paid to not significantly augment the appearance of the chin using the local. After allowing the appropriate time for vasoconstriction, the incision is made through the skin and subcutaneous tissue. We then use the sharp curved iris scissors to cut down to the mandible, but not through the periosteum. If we stay truly in the midline during this initial dissection, we can avoid small yet bothersome vessels, which are often at the lateral extents of the initial dissection. Once we identify the inferior mandibular periosteum, we dissect superiorly along the anterior face of the mandible in a supraperiosteal plane with our scissors approximately for a distance commensurate with the intended anterior augmentation. An overly large pocket can allow superior migration, and an overly small pocket can make insertion extremely difficult, if not impossible. At this point, we ensure that an adequate midline strip of periosteum is left down onto the mandible, and lateral incisions are made through the periosteum using a No. 15 blade. Then we elevate the periosteum bilaterally while hugging the inferior border of the mandible to protect the mental nerve. Using the long end of a converse retractor, we are able to fully visualize the pocket and dissect further superiorly as needed while simultaneously identifying and preserving the mental nerve. The left pocket is typically elevated more posteriorly to facilitate insertion of the implant.

With the retractor still in the pocket, slide the left side of the implant first past the midline marker. We then remove the retractor while holding onto the implant with a Brown–Adson and carefully slide the right side of the implant into the pocket using a second Brown–Adson. The implant is checked to verify that it is in the midline, and the soft tissue envelope is palpated along the implant to ensure the implant is lying flat without any bunching of the lateral ends. The midportion of the implant is sewn to the periosteum with a 4–0 Monocryl suture to secure its position. The subcutaneous closure is performed with interrupted 5–0 polydioxanone, usually one to two sutures suffice. Last, the skin is closed in a running locking fashion with 6–0 nylon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree