The vascularity of the nail apparatus occurs through the digital arteries, which run along the sides of the fingers and give rise to branches that supply both the matrix and proximal nail fold, as the arcs that supply the matrix and the nail bed. Thus, the matrix features two different sources of irrigation. In the nail bed, glomus bodies are present which are encapsulated neurovascular structures containing one to four arteriovenous anastomoses and nerve endings. Their apparent role is to regulate the vascular supply to the digits at low temperatures.

The innervation of the nail apparatus occurs via sensory nerves originating from the dorsal branches of the digital nerves, which run along the digital blood vessels.

13.1.2 Physiology

The nail plate is mainly composed of keratin (filamentous protein with low sulfur content), arranged in an amorphous matrix. Other components are water, lipids, and trace elements (primarily iron, zinc, and calcium). The keratins may be hard (80–90 % of the composition) or mild (10–20 %), and the percentage variation of their subtypes is what determines their characteristics, such as hardness and strength. The water content of the nail is variable, which is a characteristic that occurs as a result of the porosity of the nail. This means it can be hydrated and dehydrated. When the concentration falls below 16 %, the nails become brittle, and when higher than 30 %, the nail becomes opaque and flexible. Lipids are responsible for less than 5 % of the composition of the nail plate. They are under hormonal control and reduce after menopause [1, 2].

The double curvature of the nail plate along the longitudinal and transverse axes increases its resistance to stress mechanisms, especially mechanical stress.

The growth of the nail plate is continuous throughout life. On average, fingernails grow 3 mm/month and toenails grow 1 mm/month. Therefore, it takes approximately 100–180 days for full replacement of a fingernail and 12–18 months for the toenail. Due to this slow growth rate, diseases involving the nail matrix take a long time to heal and disappear [3].

The growth rate depends on the mitotic activity of the cells of the nail matrix. The nail matrix undergoes changes in and during the course of its life cycle: it has its peak around the person’s 20s and 30s, with a dramatic decrease after the age of 50 [3]. Physiological and pathological conditions can influence nail growth. Nails grow faster in certain circumstances like pregnancy, trauma, psoriasis, nail biting, and oral intake of retinoids and itraconazole. On the other hand, nails grow slower in certain instances such as vascular diseases, malnutrition, peripheral neurological diseases, and during chemotherapy [1–3].

13.2 Changes with Aging

With aging, nails undergo changes in their normal characteristics which affect some factors such as growth rate, shape, color, and the composition of the nail plate, which changes occur in addition to an increase to their susceptibility to some diseases [4, 5]. The mechanisms leading to these changes are not yet fully understood, but are probably attributable to vascular dysfunction of the extremities and the effects of sun exposure [6].

The growth rate of nails – which is typically 3 mm/month for fingernails and 1 mm/month for toenails – falls by 0.5 % per year after the age of 25. In men and women, the thickness of the nail plate in toenails and fingernails also tends to decrease [4, 5]. The composition of the nail is altered, displaying a decrease in iron and increase in calcium. These are the only confirmed changes in nails resulting from the aging process [7]. The latter findings are corroborated by a study that analyzed the improvement in the quality of nails during calcium replacement in postmenopausal women. However, no significant difference in quality was detected when compared to the control group [8] (Table 13.1).

Table 13.1

Physiological changes in nails, and its clinical representations, in aging process

Nail physiology | Changes with aging | |

|---|---|---|

Composition | Keratin (hard or light) | Iron decrease |

Water | Calcium increase | |

Lipids | ||

Trace elements (iron, zinc, and calcium) | ||

Growth | Fingernails, 3 mm/month | A decrease of 0.5 %/year |

Toenails, 1 mm/month | Drastic reduction of nail cell mitosis after the age of 50 | |

Maximum mitotic activity: person’s 20s and 30s |

Histologically, in the course of the aging process, keratinocytes increase and more thickened blood vessels and degeneration of collagen tissue may be observed in the nail bed [9].

The contour of senile nails changes. This is characterized by a reduced longitudinal curvature and an increased transversal convexity. In this age group, it is common to see nails becoming flat and broad (platonychia), spoon shaped (koilonychia), or excessively curved (pincer nail deformity) [10, 11].

The texture also undergoes changes with advanced age. It gradually loses its soft characteristic and becomes more brittle, prone to cracking, and superficial or deep longitudinal striations [9, 11].

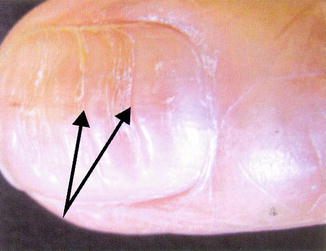

Aging of the nails is the most common cause of onychorrhexis (striations). Beau’s lines (deep grooved lines that run from side to side on the fingernail) (Fig. 13.2) and nail pitting are texture changes commonly observed in the elderly. Other changes may include trachyonychia (increased roughness), cracks, and splitting (delamination of the nail plate) [5].

The nail color also undergoes some changes, the most common being a yellowish to grayish color, with a pale and opaque look. The lunula diminishes or disappears, without displaying any pathological characteristic [9].

Other color changes usually associated with some diseases have recently been defined in the observation of non-pathological changes in normally aging nails. Among these changes, the following are worth highlighting:

Terry’s nails: nails with white color on the proximal half and pinkish color in the distal area. This change was first described in the observation of cirrhotic patients, patients with congestive heart failure, and diabetic or malnourished adults [12].

Neapolitan nails: these nails are seen in approximately 20 % of the elderly over the age of 70. They are characterized by three bands of color, like Neapolitan ice cream; the proximal area is white, the center has a normal pinkish color, and the free distal edge is opaque. This change is defined and is associated with skin changes and osteoporosis as well as probable etiology related to collagen change [13].

Some other suggestive pathological changes of the nail resulting from the aging condition of the nail apparatus may be regarded as idiopathic. Among these changes are onycholysis (detachment of the nail from the nail bed, starting from its distal and/or lateral attachment) (Fig. 13.3). This is very common in the elderly and may be idiopathic, secondary to trauma, or caused by decreased local circulation [5].

Fig. 13.3

Distal onycholysis (Image from Pontificia Universidade Catolica, Dermatology Department, Campinas, Brazil)

13.3 The Most Common Disorders in Aged Nails

Clinical nail disorders are listed in Table 13.2. Those which are observed during aging process in elderly people are approached in the next paragraphs.

Table 13.2

Morphological classification of nail changes

Change in nail plate consistency | Onychoschizia: cracks in free edge and peeling of nail plate |

Onychorrhexis: brittle, fragmented nails, with longitudinal cracks (grooves) | |

Change in nail plate thickness | Pachyonychia congenita: thickening of the nail plate |

Onychogryphosis: thickening of the nail plate, elongated and curved nail (known as “ram’s horn nails”) | |

Change in nail plate curvature | Pachyonychia congenita |

Onychogryphosis | |

Koilonychia: inversion of the nail, which becomes concave (spoon shaped) | |

Hippocratic nails (nail clubbing): watch-glass nails | |

Platonychia: flat and broad nail | |

Change in nail plate surface | Onychorrhexis |

Beau’s lines: grooved lines that run from side to side on the fingernail, resulting from the temporary interruption of nail matrix | |

Punctures or cupuliform depressions on nails (nail pitting): thimble-shaped nails | |

Median canaliform dystrophy of Heller: longitudinal splitting or canal formation in the midline of the nail. It begins in the proximal fold and progresses to the free edge as the matrix is affected | |

Nail scratching: bright nails as polished by friction from scratching | |

Change in the adhesion of the nail plate to the nail bed | Onycholysis: separation of the nail plate from the bed |

Onychomadesis: shedding of the nails beginning at its proximal end | |

Subungual keratosis: accumulation of keratin in the nail bed, away from the nail plate | |

Nail pterygium: destruction of the nail matrix and nail bed with the formation of scars by the adhesion of the nail fold to the subungual epithelium |

13.3.1 Brittle Nails

The hardness of the nail plate is determined by the concentration of water in its composition. The normal water level is approximately 18 %. Concentrations below 16 % may cause the nail plate to become brittle and above 25 % to become too flexible [9]. Studies have shown that in individuals over the age of 60, fragile nails are more common. This is caused by trachyonychia (increased roughness and longitudinal fissures), onychoschizia (nail splitting, when the horizontal lamellar separates from the distal nail plate) (Fig. 13.4), and the irregularity of the free edge of the distal nail plate [4, 14, 15].