5 Business principles for plastic surgeons

Synopsis

This chapter provides a broad overview of the essential principles that characterize what a business does and how a business does its work.

This chapter provides a broad overview of the essential principles that characterize what a business does and how a business does its work.

The ability to apply business concepts is of paramount importance if plastic surgeons are to become and remain leaders in healthcare.

The ability to apply business concepts is of paramount importance if plastic surgeons are to become and remain leaders in healthcare.

Plastic surgeons should understand and use strategy, accounting, finance, economics, marketing, and operations to help guide decisions about their practice.

Plastic surgeons should understand and use strategy, accounting, finance, economics, marketing, and operations to help guide decisions about their practice.

Innovation, entrepreneurship, and human resource management are three areas where plastic surgeons can add value to their practice and distinguish themselves from their competition.

Innovation, entrepreneurship, and human resource management are three areas where plastic surgeons can add value to their practice and distinguish themselves from their competition.

Introduction

Not only is healthcare business, it is big business.

Current estimates by the Office of Economic Cooperation and Development place healthcare spending at 16.0% of US gross domestic product, with that percentage expected to increase to 19.5% by 2017.1 For every dollar spent in the US on healthcare, 31% goes to hospital services, 21% to physicians, 10% to pharmaceuticals, 8% to nursing homes, and 30% to other categories, such as diagnostics laboratories, medical equipment, and medical devices. Of note, 7% of total spending is assigned to administrative overhead costs.

Strategy

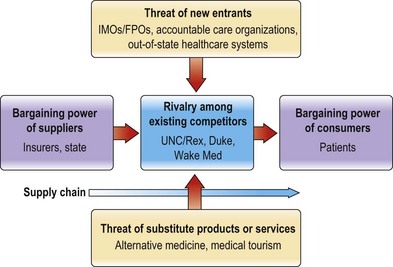

The most established and respected model of the business environment is Michael Porter’s 5-Forces model of competition (Fig. 5.1).2 Each industry contains: (1) previously established competitors; (2) the potential for new entrants; (3) the threat of substitute rivals, who often compete on price; (4) suppliers, who can have significant bargaining power; and (5) buyers, who create demand for the outputs. Understanding the environment of a specific industry, such as healthcare, can strengthen decision-making and help with strategic planning. For example, how should an academic plastic surgery practice respond to the influx of recently graduated residents into the community? How should the solo private practitioner attract new patients in a fixed market, when a group practice dominates the landscape? How should surgeons challenge scope of practice with nonsurgeon physicians and nonphysician providers? What is the optimal portfolio of services, specifically the mix of reconstructive surgery, cosmetic procedures, and skin care, to achieve the goals of the organization?

Once the dynamics and landscape of the business environment are defined, specific decisions can be made regarding change in operations, marketing, investment in new assets, alliances, or supply chain.3–5 Most mature industries, such as the automotive industry or the personal computer industry, settle into a competitive scenario in which one firm dominates with 60% market share, while a second firm contains 30% of the market share, and the remaining competitors occupy 10%. Because of barriers to entry, new entrants may not be able to compete successfully, unless disruptive technology lowers production costs or the market shifts, due to cultural, social, economic, or political forces. In fact, significant competitive advantage is conferred to small, nimble firms that focus their product line or services and offer a unique selling proposition to a targeted segment of the market. When executed correctly, this activity, termed judo strategy, has the power to undermine dominant businesses and increase market share substantially.

True value innovation comes when a company jumps out of its industry and creates an entirely new market, often in a different industry.6,7 This foray into uncharted territory, which is referred to as “white space,” typically occurs when a company develops a disruptive technology that permits the use of core competencies to produce a radically different product or service. Apple was successful in capturing the dominant position in the digital music market by designing and offering iTunes, despite being a computer company. Inherent to this success was the fact that Apple also changed the business model for purchasing music; consumers could buy singles or albums, listen to samples, and of course, use the website for free.

In summary, strategy involves the following steps:

1. Industry analysis – assess industry profitability today and tomorrow.

2. Positioning – identify sources of competitive advantage.

3. Competitor analysis – study current competitors, future entrants, and substitutes.

4. Assessment of current strategy – predict effectiveness and sustainability.

5. Option generation – search for new customers, new segments, new markets.

6. Development of capabilities – planning now for future opportunities.

7. Refining strategy – assess uniqueness, trade-offs, compatibility with vision and values.

Accounting

Business management must be based upon a common language that is used to communicate objectively information related to the quantitative metrics of an organization. That language is accounting. This section will review the tools that accountants use to assess the financial health of a business: income statement, balance sheet, summary of cash flows, and financial ratios.8–10 The nuances of accounting are beyond the scope of this overview, but healthcare providers must have a basic comprehension of these instruments and how they represent the financial standing of their practice, their hospital, and their healthcare system. Furthermore, these instruments are used in budgeting to construct pro forma predictions of future performance.

Financial ratios

Profitability ratios

Gross margin = gross profit/revenue

Operating margin = operating profit/revenue

Net margin = net profit/revenue

Return on assets = net profit/total assets

= (net income/revenue) × (revenue/assets)

Return on equity = net profit/shareholders’ equity

Contribution margin = revenue – variable direct costs

Efficiency ratios

Days in inventory = average inventory/(COGS/day)

Inventory turns = 360/days in inventory

Days sales outstanding = accounts receivable/(revenue/day)

Days payable outstanding = accounts payable/(COGS/day)

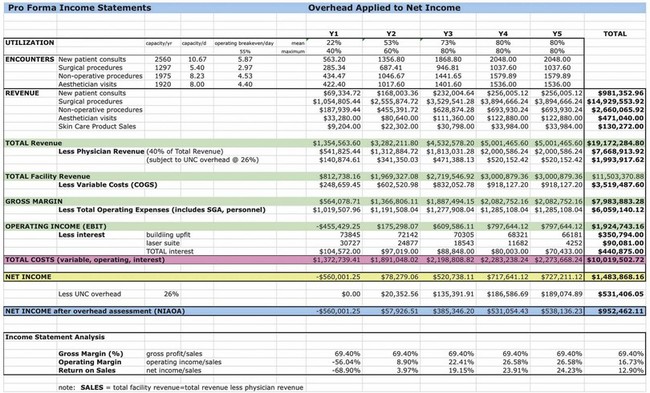

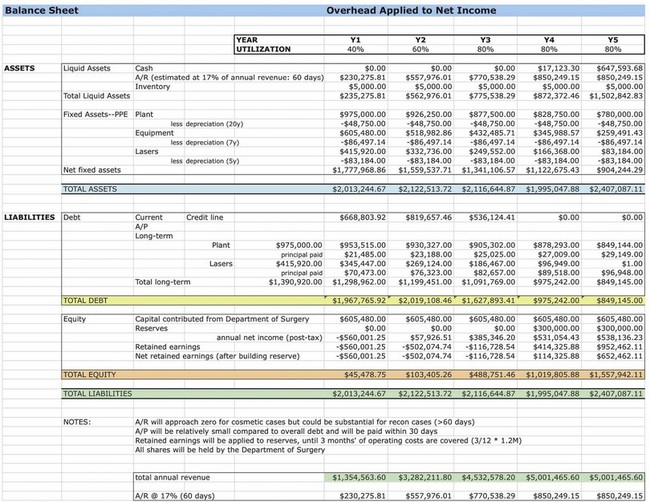

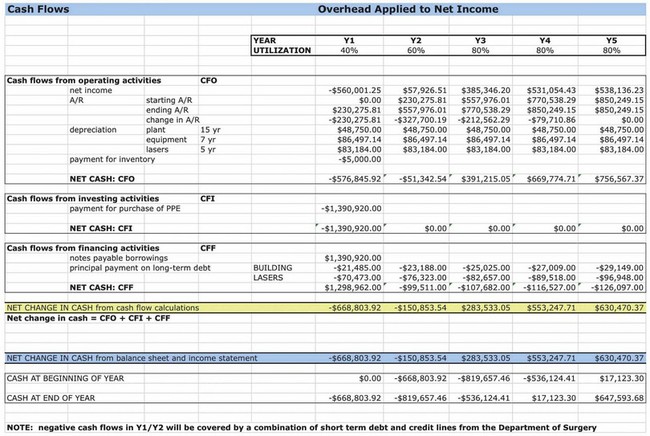

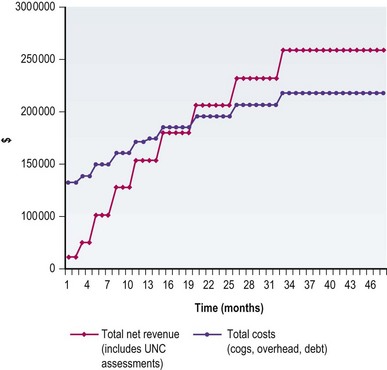

Figures 5.2–5.4 demonstrate the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flows for a proposed aesthetic and laser center that offers patient consultations, skin care, and office-based procedures. Pro formas are typically estimated for 3–5 years and include many assumptions about revenue streams, costs, and growth. Such planning is important to the success of the venture, so that real-time performance can be compared to the expected results, and changes can be implemented if necessary. Figure 5.5 demonstrates the time to breakeven, when revenue exceeds expenses, and income becomes positive.

Finance

The goal of finance is to maximize corporate value while minimizing the firm’s financial risks.11 If accounting is the language and grammar of business, then finance is a combination of poetry and theoretical physics, with some rock‘n’roll added to keep the mix interesting. The central thesis of finance is that risk can be managed successfully, in such a way that wealth is created, by combining the variables of cash, assets, supply chain, and human capital, to produce a good or service that is more valuable than the cost of production. The consumer, however, is the final arbiter who decides if the good or service is more valuable than the cost of the inputs, and if the output is more valuable than the price the consumer is willing to pay. If so, the consumer exchanges money for the good or service.

Economics

Like other branches of economics, healthcare economics deals with decision-making in the setting of uncertainty, limited resources, and variable demand.12–14 However, healthcare economics is distinctly different from other branches of economics, because healthcare is an industry that includes extensive government intervention and regulation; asymmetry of information between provider, patient, and payer; lack of precise metrics, with regard to patient outcomes; and considerable externalities, which are the downstream effects on other entities, outside the healthcare system.

Marketing

Business could not exist without the customer, and marketing is the process that enables business to connect with the customer.15,16 Marketing strategy identifies, attracts, satisfies, and retains customers. Seeking to build more than a single exchange between the producer and the consumer (or in healthcare, the provider and the patient), marketing is first and foremost driven by customer needs and desires. The ideal approach in marketing is initially to understand the customers in the context of their environment, which includes not only assessment of market size but also competitive forces, barriers to entry, and market structure. Next, marketing seeks to develop a specific product or service offering, based upon anticipated customer needs that may or may not be adequately met, or may not even be appreciated. Finally, marketing strives to deliver customer value, in the form of price point, quality, and distribution.

To achieve a specific profit target, the formula can be modified as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree