FIGURE 10–1 Jackson’s Concentric Zones of burn tissue Jackson’s burn theory classifies three concentric zones in relation to the potential viability of the tissue. These regions from the center of the wound to the periphery were labeled as the zone of coagulation, zone stasis and the zone of hyperemia. The center zone of coagulation is the area of maximum contact to the thermal source. Tissues in this area undergo a coagulation necrosis as proteins of the extracellular matrix are denatured and vascularity is impaired. Cells will not recover and emphasis is placed on early debridement and prevention of infection. The intermediate zone of stasis is characterized by hypoperfusion and hypometabolism as the numbers of viable cells are substantially reduced. Phenotypically this area appears as blanching erythema when pressure is applied. There is a risk of tissue progression to necrosis if proper care is not taken to preserve tissue perfusion by adequate fluid resuscitation, avoidance of vasoconstrictors, and prevention of infection. Patients with significant co-morbidities that impair blood flow such as diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and tobacco use are at increased risk for irreversible injury. The outer zone of hyperemia also appears as erythema as the result of local vasodilatation. Cells in this zone are completely viable and will recover if protected from further trauma and/or infection.

BURN WOUND CLASSIFICATION

Depth of Penetration

The severity of the burn injury and treatment algorithm is determined by the depth of penetration and the surface area of injured skin in relationship to the total body surface area (TBSA) of the patient. The previous designation of first, second, and third degree burns has been replaced by the designations of superficial, partial thickness, and full thickness, respectively, because of the heterogeneity within the spectrum of burn depth.

Superficial injuries are burns limited to the epidermis without disruption of epithelial integrity (FIGURE 10-2). This injury was previously designated “first-degree burn.” These injuries are characterized by erythema of the skin secondary to vasodilatation of local capillaries. Sunburns are examples of superficial burns and after 3 to 4 days, the damaged epithelium desquamates and is replaced by regenerating keratinocytes.4

FIGURE 10–2 Superficial burn Superficial burns involve only the epidermis and will heal in 3-4 days without scarring or medical intervention. Sunburn on the shoulder of this toddler is an example of a superficial burn.

Partial-thickness, previously second-degree, burns are heterogeneous in nature due to the differences in dermal thickness regionally, and in pathophysiology related to differences in superficial and deep injuries to the dermis. The primary state of a partial-thickness burn is that dermal structures are still intact and thus spontaneous healing may occur through migration of epithelial progenitor cells from dermal appendages. However, the healing potential of superficial partial-thickness burn may be much better than a deep partial-thickness burn because of the absolute amount of dermis that is viable. This heterogeneity difference in healing potential, and the correlating need for possible excision and grafting, have resulted in the designation of superficial partial-thickness and deep partial-thickness injury.

Superficial partial-thickness burns are dermal injuries that extend into the papillary dermis (FIGURE 10-3). These wounds are sensate, blanch with pressure, and typically result in blistering as a result of the local inflammatory process between the dermis and the epidermis. These wounds heal within 2 to 3 weeks by epithelization and rarely form hypertrophic scarring and/or wound contracture. Thus, they do not require excision and grafting. Deep partial-thickness injuries extend into the reticular dermis and are insensate, have a mottled white appearance, and do not blanch with pressure as the result of impaired vascularity and capillary refill (FIGURE 10-4). The reticular dermis is the location of skin appendages and injury in this area can cause permanent damage to hair follicles and sebaceous glands. If allowed to heal by secondary intention, deep partial-thickness burns heal in 3 to 9 weeks with significant hypertrophic scarring and wound contracture; thus they are best treated by debridement of necrotic tissue and skin grafts. Wound contractures can lead to considerable functional impairment especially if they occur in vital areas like the hands, neck, or face. Thus, deep partial-thickness injuries are more likely to heal better with excision and grafting procedures, despite the possibility of secondary healing.

FIGURE 10–3 A. Superficial partial-thickness burns Superficial partial-thickness burns involve the epidermis and the superficial dermis. They are characterized by intense pain, blanching with pressure, and blistering as a result of the local inflammatory process between the dermis and epidermis. These wounds heal within 2-3 weeks by epithelization and rarely form hypertrophic scarring and/or wound contracture. A scald burn on the lower extremity with sloughing of the epidermis is an example of a superficial partial-thickness burn; the areas that are mottled and nonblanching are deep partial-thickness burns. B. Superficial partial thickness burn re-epithelializing The thermal burn on the plantar foot is superficial partial thickness, and islands of new epithelium can be observed in the middle of the wound. The blistered tissue was debrided, but the wound healed without grafting.

FIGURE 10–4 Deep partial thickness burn Deep partial thickness injuries extend into the reticular dermis and are insensate, have a mottled white appearance, and do not blanch with pressure as the result of impaired vascularity and capillary refill. Deep partial-thickness burns heal in 3 to 9 weeks, sometimes with significant hypertrophic scarring and wound contracture; therefore, they are best treated by debridement of necrotic tissue and skin grafts.

Full-thickness injuries are dermal injuries extending through the entire dermis and across the subdermal plexus, owing to complete loss of the epithelial barrier (FIGURE 10-5). The previous designation was a “third-degree burn”. This designation also implies that there is no possibility of healing from the wound base, as all dermal regenerative cells have been obliterated. The physical appearance is leathery brown or black eschar with no capillary refill. The wounds are insensate and treatment is focused on early excision and grafting to prevent infection, hypertrophic scarring, and wound contracture. Depending on size and location, most full-thickness injuries will require excision and grafting procedures.

FIGURE 10–5 Full thickness burn Full thickness burns extend through the entire dermis and into the subcutaneous tissue. The appearance is leathery brown or black eschar with no capillary refill. The wounds are insensate and treatment is focused on early excision and grafting to prevent infection, hypertrophic scarring, and wound contracture. This foot with extensive eschar and exposed subcutaneous tissue is an example of a full thickness burn.

The extent of burn penetration may not be readily apparent at the time of initial evaluation. Although many tools have been used as predictive indicators of depth of injury (eg, biopsy, ultrasound, or perfusion techniques), none have proven to be as reliable as a physical examination at 48 to 72 hours postinjury.5

Size of Burn Injury

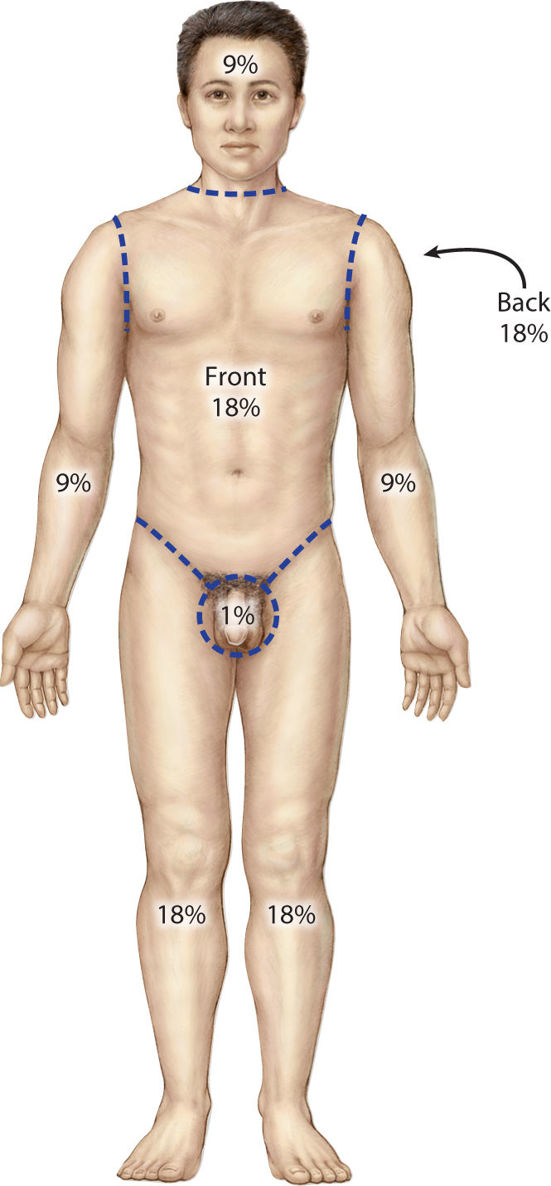

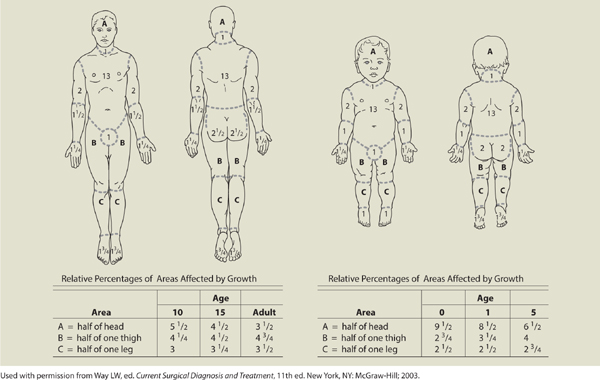

An estimate of the burn wound surface area in proportion to the TBSA is used to estimate the total fluid and caloric requirements, and is a predictor of mortality. For an adult patient, the burn area can be generalized utilizing the “rule of nines” (FIGURE 10-6). More sophisticated charts have been developed to estimate the body surface in relationship to age and may be more useful particularly in the pediatric population (TABLE 10-1). The depths of penetration as well as the TBSA burn are major determinants by American Burn Association for referral to a regional burn center for a higher level of care (TABLE 10-2).

FIGURE 10–6 Rule of Nines The Rule of Nines is used to determine total body surface area that is burned and estimates that each upper extremity accounts for 9 percent of the total burn surface area or TBSA, and each lower extremity, 18 percent. In addition, the anterior and posterior trunk is predicted to be 18 percent, the head and neck 18 percent and the perineum 1%. For burns spanning anatomical regions, the volar surface area of the hand may be considered 1% of the TBSA.

TABLE 10-1 Estimating Total Surface Burn Area

TABLE 10-2 Criteria for Referral to a Regional Burn Center

American Burn Association Criteria for Referral to Regional Burn Unit

Data from www.ameriburn.org

MECHANISMS OF BURN INJURIES

Scald

Scald burns are the result of contact with hot liquids and are the most common burn etiology in developed countries. The extent of injury is dependent on the temperature and viscosity of the liquid and the duration of exposure, in addition to patient factors and anatomical location. Exposure to hot water above 60°C for 3 seconds can result in deep partial-thickness or full-thickness injury. These injuries typically appear less severe in exposed areas of the body. Clothed areas typically have more extensive injuries because clothing retains heat and remains in contact with the skin for a longer duration of time. In the pediatric population, immersion scald burns with a symmetric distribution of the upper extremity or lower extremity and/or perineal and buttocks should warrant suspicion of abuse and health care professionals are required to notify appropriate child protective agencies (FIGURE 10-7).

FIGURE 10–7 Scalding burn This toddler’s hand is an example of a superficial partial thickness burn due to scalding water. The depth of tissue injury depends on the liquid temperature and time of exposure. Any suspicion of child abuse with this type burn should be reported to the Children’s Protective Services.

Scald burns from grease result in more severe injuries as grease is more viscous than water, therefore resulting in a longer duration of contact. In addition, grease can reach higher temperatures, usually around 200°C. Grease burns frequently cause deep partial-thickness to full-thickness burns. Tar is a unique type of scald burn that requires specialized management because it becomes adherent to the skin as it cools. Treatment is initially focused on slow removal of the tar with petroleum-based ointment like Neosporin (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) or Medi-sol (Medi-sol, Oklahoma City, OK). The ointment may need to be applied multiple times in order to totally dissolve the tar. Once dissolved, appropriate assessment can be made regarding the depth of penetration and extent of injury.

Flame

Flame injuries are the second most common mechanism of burns and the most common mechanism requiring hospitalization. Flame injuries account for 44% of burn admissions in the United States annually.2 The incidence of flame burns has significantly decreased with the implementation of prevention programs and improved detection methods such as smoke detectors and fire alarms. The major determinant of morbidity and mortality in this patient population is the presence of concomitant inhalation injury.6 Inhalation injury should be suspected if the burn occurred within an enclosed space or if physical examination reveals singed nasal hair and/or carbonaceous sputum.

Electrical

Electrical burns have been described as the most devastating burn injuries because they not only involve the skin, but underlying organ systems as well (eg, the cardiovascular and nervous systems). As electrical energy travels through the body, it is converted to heat, and the severity of injury is dependent on voltage, type of current (alternating vs direct), the pathway traveled through the victim’s body, and the electrical resistance. Electrical injuries are classified as low voltage (<1000 V) and high voltage (≥1000 V). Low voltage typically involves tissues immediately surrounding the point of initial contact, while high voltage usually results in penetration to deeper organ systems. Alternating current causes tetanic contractions that can prevent the victim from releasing the source, thereby resulting in prolonged contact with the electricity and thus more devastating injuries. Smaller body parts such as the hands, fingers, and feet generate more heat because they dissipate less heat to the surrounding tissues, and in many cases injures to these structures result in complete necrosis (FIGURE 10-8). An electrical burn typically has three injury components that need to be evaluated: a true electrical energy injury from current flow, an arc or flash flame injury by a current arcing at a temperature around 7200 degrees F from the source to the ground, and a flame injury via ignition of clothing. The extent of injury can be easily underestimated because the phenotypic appearance may be limited, while underlying muscle necrosis may be extensive. Complications of electrical injuries include rhabdomyolysis leading to hyperkalemia, acidosis, myoglobenemia, and renal failure.

FIGURE 10–8 Electrical burn Electrical burns on smaller body parts such as the hand frequently result in full-thickness tissue loss with necrosis. The patient with this type of wound should be referred to a regional burn center.

Treatment of electrical burns is focused on aggressive fluid hydration, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, alkalinization of the urine, and diuresis. Muscle edema may also lead to compartment syndrome and should be suspected if the patient complains of progressive pain and paresthesia. In these cases, an emergent fasciotomy should be performed to prevent progressive tissue hypoperfusion and necrosis. Cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation, and cardiac arrhythmias are common within the first 48 hours and can be life threatening. Indications for cardiac monitoring are documented ECG abnormalities, observed arrhythmias, large burn size, or advanced age. In addition, transient and permanent nerve injuries including peripheral neuropathy, delayed transverse myelitis, and anterior spinal syndrome have been reported.

Lightning strikes are a rare type of electrical injury resulting from a direct current that can generate heat as high as 50,000 degrees F. Due to the short duration of action, usually of 1 to 2 milliseconds, frank skin necrosis is uncommon. Patients typically demonstrate superficial skin manifestations of a fernlike pattern, related to the flow of electrons over the body surface, and termed Lichtenberg figures (FIGURE 10-9). These lesions are transient, lasting only for 24 hours, and death is usually the result of cardiac arrest and apnea from direct effects of the current on the central nervous system. Lightning can also cause punctate wounds as seen in FIGURE 10-10.

FIGURE 10–9 Lichtenberg figures with lacy ferning pattern seen on the upper chest. (Used with permission from Zafren K, Thurman R, Jones ID. Chapter 16. Environmental Conditions. In: Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman R. eds. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

FIGURE 10–10 Punctate lightning burn (Used with permission from Zafren K, Thurman R, Jones ID. Chapter 16. Environmental Conditions. In: Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman R. eds. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

Chemical

Chemical burns occur secondary to the contact of the skin with strong acids or alkali. Concentration of the agent, quantity, duration of contact, and the mechanism of action in a biological system are factors that determine the severity of the chemical burn injury. Acidic burns tend to be less severe as contact results in a coagulation necrosis of the tissue. On the other hand, alkaline agents result in a liquefaction necrosis of tissue, which causes a deeper extension of injury. Initial management of chemical burns is focused on removal of the agent from the skin by copious water irrigation. It is imperative that the irrigation be carried out in the form of lavage instead of submerging the patient in a contained space like a tub, which will maintain contact with the source.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree