Bullous Pemphigoid: Introduction

|

Bullous pemphigoid was originally classified as a unique disease with distinctive clinical and histologic features by Walter Lever in 1953.1 Its separation from pemphigus was important, because at the time pemphigus vulgaris was often fatal, whereas bullous pemphigoid had a comparatively good prognosis. The separation of bullous pemphigoid from pemphigus was confirmed and fully justified by the characteristic immunopathologic features of these diseases described approximately 12 years later.2,3

Epidemiology

Bullous pemphigoid typically occurs in patients over 60 years of age, with a peak incidence in the 70s.4 There are several reports of bullous pemphigoid in infants and children, although this is rare.5–8 There is no known ethnic, racial, or sexual predilection for developing bullous pemphigoid. The incidence of bullous pemphigoid is estimated to be 7 per million per year in both France and Germany, and 14 per million per year in Scotland.4,9–11 A recent large cohort study suggests that the incidence of bullous pemphigoid may be as high as 43 per million per year in the United Kingdom with incidence increasing over the last several years.12

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The hallmarks of bullous pemphigoid include the presence of subepidermal blisters, lesional and perilesional polymorphonuclear cell infiltrates in the upper dermis, and immunoglobulin (Ig) G autoantibodies and C3 bound to the dermal epidermal junction. Remarkable advances have been made in the last decades characterizing the antigens as hemidesmosomal components and developing an animal model that demonstrates the pathogenicity of bullous pemphigoid autoantibodies.

Immunofluorescence (IF) techniques demonstrate that patients with bullous pemphigoid exhibit circulating and tissue-bound autoantibodies directed against antigens of the cutaneous basement membrane zone (BMZ).3 Immunoelectron microscopy studies localize bullous pemphigoid antigens to the hemidesmosome, an organelle that is important in anchoring the basal cell to the underlying basement membrane.13 These autoantibodies bind to both the intracellular plaque of the hemidesmosome and the extracellular face of the hemidesmosome. Bullous pemphigoid autoantibodies recognize two distinct antigens with molecular weights of 230 kDa and 180 kDa by immunoblot analysis of human skin extracts.14 The 230-kDa molecule is termed BP230, BPAG1, or BPAG1e.14–17 BPAG1e belongs to a gene family that includes desmoplakin I, a desmosomal plaque protein that is important in anchoring keratin intermediate filaments to the desmosome.18,19 By immunoelectron microscopy BPAG1e is located in the intracellular plaque of the hemidesmosome, exactly where keratin intermediate filaments insert.20 Analysis of BPAG1e-deficient mouse strains generated by transgenic knockout technology further demonstrates that the function of BPAG1e is to anchor keratin intermediate filaments to the hemidesmosome.21 Mice lacking BPAG1e show fragility of basal cells due to collapse of the keratin filament network, but no epidermal–dermal adhesion defect. Interestingly, an alternatively spliced form of BPAG1e (termed BPAG1n) is expressed in neural tissue. BPAG1n stabilizes the cytoskeleton of sensory neurons,22,23 just as BPAG1e stabilizes the cytoskeleton of epidermal cells. The lack of dermal–epidermal separation in the BPAG1e-null mice indicates that pathogenic autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid do not act simply by inhibiting the function of BPAG1e.

The 180-kDa BP autoantigen is termed BP180, BPAG2, or type XVII collagen.24–26 BP180 is a transmembrane protein with an intracellular amino-terminal domain and an extended carboxyl-terminal domain that spans the lamina lucida and projects into the lamina densa of the basement membrane.27–31 Its cytoplasmic domain is located in the plaque of the hemidesmosome and its extracellular domain is linked to anchoring filaments.32–34 The extracellular domain of BP180 contains a series of 15 collagen regions interrupted by 16 noncollagen sequence.29 The NC16A subdomain, adjacent to the membrane-spanning region, harbors the major autoantibody-reactive epitopes.35,36 These features make the BP180 antigen a prime target for pathogenic autoantibodies. As discussed in Section “Pathophysiology of Subepidermal Blistering,” antibodies against the NC16A domain are capable of inducing subepidermal blisters in mice. Moreover, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure antibodies against the BP180 NC16A domain is both sensitive and specific for a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid37–39 and its titers correlate with disease activity.40 Further evidence that BP180 mediates dermal–epidermal adhesion comes from analysis of the gene defect in patients with the junctional subepidermal blistering disease, non-Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB-nH), previously known as generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. These patients have recessively inherited mutations in the BP180 gene that result in a missing or dysfunctional protein.41–43

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune inflammatory disease. The distinctive feature of bullous pemphigoid is the presence of circulating and tissue-bound autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230. Anti-BP180 autoantibodies of various immunoglobulin isotypes and IgG subclasses are present in bullous pemphigoid sera with IgG being predominant, followed by IgE.44–46 Serum levels of anti-BP180-NC16A IgG and IgE correlate well with disease activity in bullous pemphigoid patients.24,26,40 Inflammatory cells are present in the upper dermis and bullous cavity, including eosinophils (the predominant cell type), neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes/macrophages. Both intact and degranulating eosinophils, neutrophils, and mast cells (MC) are found in the dermis.47–50 Local activation of these cells may occur via the multiple inflammatory mediators present in the lesional skin and/or blister fluid.51–59 Several proteinases are found in bullous pemphigoid blister fluid, including plasmin, collagenase, elastase, and MMP-9,60–67 which may play a crucial role in subepidermal blister formation by their ability to degrade extracellular matrix proteins.

Both in vitro and in vivo data demonstrate that autoantibodies, particularly those against BP180, are pathogenic. In vitro studies using normal human skin sections indicate that bullous pemphigoid IgG is capable of generating dermal–epidermal separation in the presence of complement and leukocytes.68,69 Early attempts to demonstrate the pathogenicity of patient autoantibodies by a passive transfer mouse model were unsuccessful because bullous pemphigoid anti-BP180-NC16A autoantibodies fail to cross-react with the murine BP180.70 To overcome this difficulty, rabbit antibodies were raised against the epitope on mouse BP180. Passive transfer of these rabbit antibodies to neonatal mice induces blisters that resemble some key features of human bullous pemphigoid, including in situ deposition of rabbit IgG and mouse C3 at the BMZ, dermal–epidermal separation, and an inflammatory cell infiltrate.70 These studies demonstrate that experimental blistering in animals requires activation of the classical pathway of the complement system, mast cell degranulation, and neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 56-1).71–75 A well-orchestrated proteolytic event occurs during the disease progression. Plasmin activates proenzyme MMP-9 and activated MMP-9 then degrades α1-proteinase inhibitor, the physiological inhibitor of neutrophil elastase. Unchecked neutrophil elastase degrades BP180 and other extracellular matrix components, resulting in dermal–epidermal junction separation.76–79 To directly test the pathogenicity of anti-BP180 IgG autoantibodies from bullous pemphigoid patients, humanized BP180 mouse strains were generated, in which the human BP180 or NC16A domain replaces the murine BP180 or corresponding domain.80,81 These humanized mice, upon injection with anti-BP180 IgG from bullous pemphigoid patients, develop subepidermal blisters.80,81 Like the rabbit antimurine BP180 IgG-induced model, the humanized NC16A mouse model of bullous pemphigoid also requires complement, MC, and neutrophils (Fig. 56-2).80

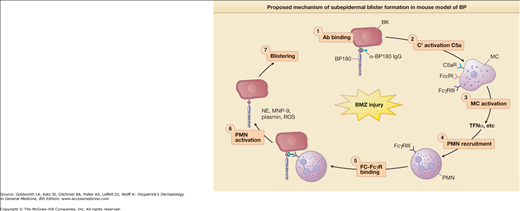

Figure 56-1

Proposed mechanism of subepidermal blister formation in mouse model of BP. Subepidermal blistering is an inflammatory process that involves the following steps: 1, anti-BP180 IgG binds to the pathogenic epitope of BP180 antigen on the surface of basal keratinocytes (BK); 2, the molecular interaction between BP180 antigen and anti-BP180 IgG activates the classical pathway of the complement system (C′); 3, C′ activation products C3a and C5a cause mast cells (MC) to degranulate; 4, TNF-α and other proinflammatory mediators released by MC recruit neutrophils (PMN); 5, infiltrating PMNs bind to the BP180–anti-BP180 immune complex via the molecular interaction between Fcγ receptor III (FcγRIII) on neutrophils and the Fc domain of anti-BP180 IgG; 6, the interaction between Fc and FcγRIII activates PMNs to release neutrophil elastase (NE), gelatinase B (MMP-9), plasminogen activators (PAs), and reactive oxygen species (ROS); 7, Proteolytic enzymes and ROS work together to degrade BP180 and other extracellular matrix proteins, leading to subepidermal blistering.

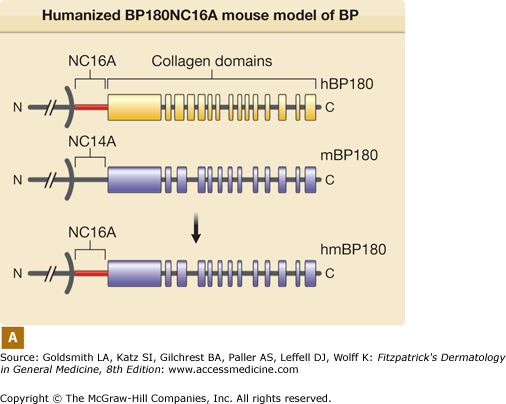

Figure 56-2

Humanized BP180NC16A mouse model of BP. A. Human BP180 (top panel) is a transmembrane protein of basal keratinocytes. It contains a single transmembrane domain. The extracellular region is consisted of 15 interrupted collagen domains (yellow bars) and 16 noncollagen domains (black lines). The NC16A domain (red line) harbors immunodominant epitopes recognized by BP autoantibodies. The extracellular region of mouse BP180 (middle panel) contains 13 collagen domains (blue bars) and 14 noncollagen domain (black lines). In humanized BP180NC16A mice, the mouse BP180NC14A domain was replaced by the human NC16A domain (lower panel). B. Neonatal NC16A mice injected i.d. with BP180NC16A-specific IgG autoantibodies developed clinical blistering (a). Direct IF showed BMZ deposition of human IgG (b) and murine C3 (c). Histological sections of lesional skin showed dermal–epidermal separation (d). Examination of toluidine blue-stained skin sections revealed degranulating mast cells (MC) (e). Hematoxylin/Eosin (H/E) staining showed infiltrating neutrophils (PMN) in the upper dermis (400× magnification) (f). E = epidermis; D = dermis; V = vesicle; arrows in panels b–d = basal keratinocytes.

IgE anti-BP180 autoantibodies may also play a role in blister formation. Human skin grafted onto immune-deficient mice injected with an IgE hybridoma to the extracellular portion of BP180 or total IgE from bullous pemphigoid patients’ sera exhibit histological dermal–epidermal separation,82,83 suggesting that anti-BP180 IgE antibodies may also participate in pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid through activating MC and recruiting eosinophils.

Although animal model studies clearly show that an inflammatory cascade is triggered by BP180-specific antibodies and is essential for blister formation, direct interference of hemidesmosome-mediated cell–cell matrix adhesion by anti-BP180 autoantibodies may be another disease mechanism.84 Involvement of anti-BP230 autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid blistering is also implicated in some animal model studies,85,86 but direct evidence in humans is lacking.

In addition to the humoral response, bullous pemphigoid patients also mount a cell mediated autoimmune response. Autoreactive T and B lymphocytes recognize BP180.87–89 These studies suggest that bullous pemphigoid is a T- and B-cell-dependent and antibody-mediated skin autoimmune disease. As in most autoimmune diseases, the initial trigger for induction of autoreactive lymphocytes and autoantibody production in bullous pemphigoid remains unknown.

Several other subepidermal blistering diseases also show autoimmune responses to BP180. These include pemphigoid gestationis (or herpes gestationis), cicatricial pemphigoid (or mucous membrane pemphigoid), linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and lichen planus pemphigoid.90–100 It is possible that they may share some common immunopathological mechanisms with bullous pemphigoid.

Clinical Findings

Most cases of bullous pemphigoid occur sporadically without any obvious precipitating factors. However, there are several reports in which bullous pemphigoid appears to be triggered by ultraviolet (UV) light, either UVB or following PUVA therapy, and radiation therapy.101–103 Certain medications have also been associated with the development of bullous pemphigoid including penicillamine, efalizumab, etanercept, and furosemide.104–109

The classic form of bullous pemphigoid is characterized by large, tense blisters arising on normal skin or on an erythematous base (Fig. 56-3A).110,111 These lesions are most commonly found on flexural surfaces, the lower abdomen, and thighs, although they may occur anywhere. The bullae are typically filled with serous fluid, but may be hemorrhagic. The Nikolsky and Asboe–Hansen signs are negative. Eroded skin from ruptured blisters usually heals spontaneously without scarring, although milia can sometimes occur. Once the lesions heal they leave hyperpigmented patches that may last for several months. Pruritus may be intense in some patients, but minimal in others.

Nonbullous lesions are the first manifestation of bullous pemphigoid in almost half of patients.112 Often, urticarial type lesions precede the more classic tense bullae, and patients may present with these lesions early in the course of disease (Fig. 56-3B). The erythematous component in some bullous pemphigoid patients may appear eczematoid, serpiginous, or targetoid with erythema multiforme-like lesions.

Mucous membrane lesions occur in approximately 10% of patients and are almost always limited to the oral mucous membranes, particularly the buccal mucosa.110,113–115 Intact oral mucosa blisters are rare, with erosions more commonly seen. The lesions heal without scarring and are fairly limited. Unlike erythema multiforme, the vermillion border of the lips is rarely involved. There are rare reports of esophageal involvement.116,117 The presence of scarring is more suggestive of cicatricial pemphigoid as discussed in Chapter 57.

In addition to the more classic findings, unusual clinical presentations can be seen.118 In these cases, the diagnosis is confirmed by IF and ELISA studies. For example, localized bullous pemphigoid often presents as tense bullae restricted to localized areas of involvement, most commonly on the lower legs.119,120 Patients with localized disease have antibodies against the same pemphigoid antigens as patients with more generalized disease.119–121 The lesions may remain localized for years or progress to generalized bullous pemphigoid. Childhood bullous pemphigoid often presents as localized disease with acral distribution being common.5–8,122 Localized vulvar and perivulvar disease has also been described in young girls.123,124 Other reports of localized bullous pemphigoid suggest that changes induced by radiation, trauma, or surgery (colostomy, urostomy, or skin graft donor site) at a particular site may precipitate disease in these areas.125–133

Other less common presentations include erythroderma, prurigo nodularis-like or vegetating lesions, and dyshidrotic dermatitis-like lesions. Again, the antibodies from these patients show typical IF localization and bind the pemphigoid antigens.121,134–142

In addition to atypical clinical presentations, bullous pemphigoid may also coexist with other cutaneous diseases. Lichen planus pemphigoides describes the coexistence of bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus with typical clinical, histologic, and immunopathologic features of both diseases.143–146 Lichen planus pemphigoides more often presents in middle-aged patients (mean age of onset 35–45 years of age) and is more localized to the extremities with a less severe clinical course when compared to classic bullous pemphigoid. In rare instances, bullous pemphigoid has also been reported to coexist with pemphigus.147–150

Neurological disease is seen more frequently in bullous pemphigoid patients and it appears that patients with neurological disease (especially those over 80 years of age) have a significantly higher risk of developing bullous pemphigoid than those without neurological disease.151–153 In rare instances, bullous pemphigoid may be seen in association with acquired hemophilia due to acquired Factor VIII inhibitor. Cutaneous clinical manifestations include ecchymoses, hematomas, and hemorrhagic bullae in addition to more systemic findings such as gastrointestinal bleeding.154–156

There have been many case reports of bullous pemphigoid associated with malignancy. However, case-control studies suggest that there is no increase, or a very small increase, in the frequency of malignancy in bullous pemphigoid patients compared with age-matched controls.152,157–159 There may be an increased frequency of malignancy in bullous pemphigoid patients with negative indirect IF studies as compared with those with positive findings.113,160 The perceived association may be explained by the fact that both bullous pemphigoid and malignancy occur more commonly in elderly patients. While a thorough review of systems and symptom-guided workup is indicated in patients with a new diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid, extensive screening for an asymptomatic malignancy is not warranted.

The diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid is made based upon clinical, histologic, and IF features as described below. Other laboratory studies play a small supporting role. Approximately half of patients will have elevated total serum IgE levels, which often correlate with titers of bullous pemphigoid IgG autoantibodies by IF and pruritus.51,161,162 Approximately one-half of patients have peripheral blood eosinophilia, which does not correlate with serum IgE levels.162,163

Histopathology

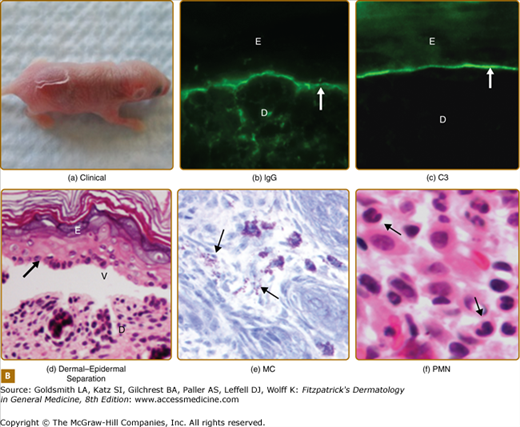

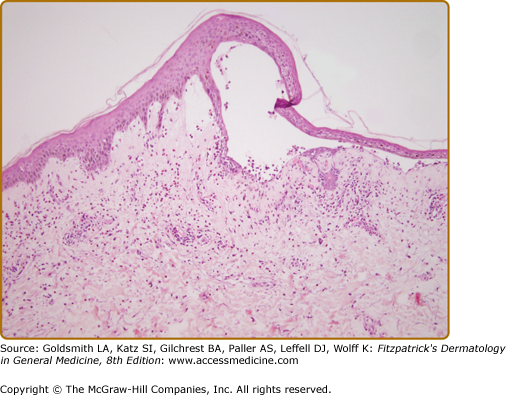

Biopsy of an early small vesicle is diagnostic with histology revealing a subepidermal blister with a superficial dermal infiltrate consisting of eosinophils, neutrophils lymphocytes, and monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 56-4).110 The infiltrate ranges from intense to sparse, but it characteristically contains some eosinophils, which may also be seen in the blister cavity. The blister roof is usually viable without evidence of necrosis. Histology of urticarial lesions may only show a superficial dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and eosinophils with papillary dermal edema. These urticarial lesions may also display degranulating eosinophils at the dermal–epidermal junction, with early separation of individual basal cells from the basement membrane and/or eosinophilic spongiosis.164

Ultrastructural studies demonstrate that early blister formation in bullous pemphigoid occurs in the lamina lucida, between the basal cell membrane and the lamina densa (Fig. 56-5A and 56-5B).165 In areas of blister formation, there is loss of anchoring filaments and hemidesmosomes. Degranulation of eosinophils, neutrophils, and MC in the lesional/perilesional skin has also been observed by electron microscopy.49

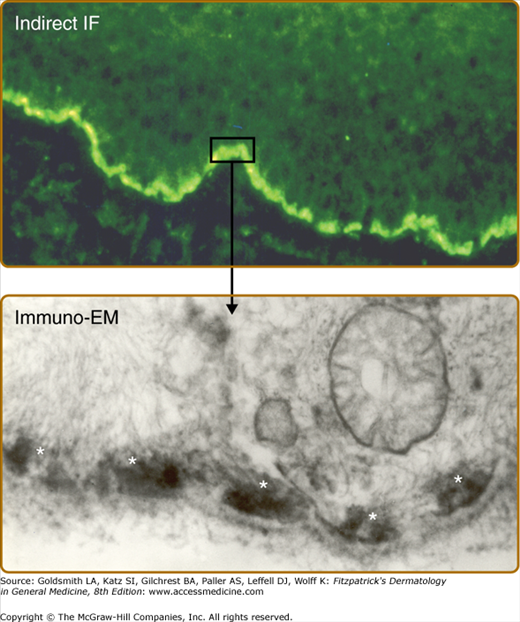

Figure 56-5

A. Indirect immunofluorescence of bullous pemphigoid serum shows a linear pattern of immunoglobulin G binding to the epidermal dermal junction of normal skin. B. Binding of bullous pemphigoid antibodies to human basal cell hemidesmosomes as described by Mutasim et al: J Invest Dermatol 84:47-53, 1985. A small rectangle of linear indirect IF staining and the arrow depicts the immunolocalization of the reactive antibodies to the hemidesmosome (white asterisks).

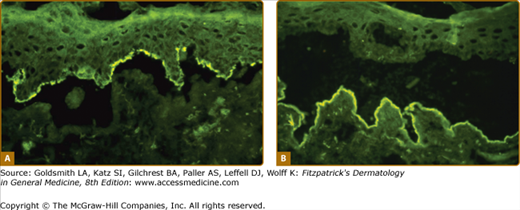

Direct IF of perilesional skin shows linear IgG (usually IgG1 and IgG4, although all IgG subclasses and IgE have been reported) and C3 along the basement membrane.2,3,113,162,166 In approximately 70% of patients, there are circulating IgG and IgE autoantibodies that bind the BMZ on normal human skin or monkey esophagus by indirect IF.45,113,162,163,166–169 Using 1 M NaCl split skin, which separates the epidermis from the dermis at the lamina lucida, an even higher percentage of patients will have detectable circulating anti-BMZ autoantibodies.170,171 In addition to being more sensitive, the other advantage of the 1 M NaCl-split skin substrate is that bullous pemphigoid antibodies bind the roof of the artificially induced blister (i.e., the bottom of the basal cells). This finding differentiates bullous pemphigoid antibodies from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) autoantibodies, which bind the base or the floor of the split skin (i.e., dermal side; Figs. 56-6A and 56-6B). In contrast to pemphigus, in bullous pemphigoid the indirect IF antibody titer does not usually correlate with disease extent or activity.172

Figure 56-6

Indirect immunofluorescence on normal skin previously incubated in 1 M NaCl to induce a split through the lamina lucida of the dermal–epidermal junction. A. IgG antibodies from bullous pemphigoid serum binds to the roof of the artificial blister (hemidesmosomes). B. IgG antibodies from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) serum binds to the floor of the split (collagen VII of anchoring fibers).

Recently, ELISA techniques have proven to be useful in both clinical and research settings for the detection of circulating antigen specific IgG and IgE antibodies. Commercial kits are available for detection of both BP-180 (NC16A and total) and BP-230 IgG antibodies. A sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 98% when used with appropriate cutoff values are reported with these assays.37 As many as 75% of patients also have antigen specific IgE with anti-BP180 and anti-BP230 IgE antibodies detectable by IF and ELISA.44,46,168,173–176 Those patients with anti-BP180 IgE antibodies may have a more severe form of disease.174 Antigen specific IgE antibodies may account for the early urticarial type lesions and likely play a role in recruiting eosinophils to skin lesions.82,173

Recent studies have shown that approximately 7% of the normal population has anti-BP180 antibodies detectable by ELISA in the absence of clinical and histologic features of disease without age or gender predilection. The predictive relevance of these circulating antibodies in healthy individuals is unknown as long-term follow-up is not available. However, this finding underscores the importance of using the ELISA in appropriate clinical settings and not as a screening tool in patients who lack other features of disease.177

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for bullous pemphigoid includes other blistering diseases, such as linear IgA disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, erythema multiforme, EBA, and pemphigus. Histology and IF can easily distinguish bullous pemphigoid from these diseases (Box 56-1). Distinguishing bullous pemphigoid from EBA and cicatricial pemphigoid may be difficult as histology and direct IF may be identical.115,178 EBA can usually be distinguished from bullous pemphigoid by indirect or direct IF on salt-split skin as stated above.179 Confirmation of EBA may be accomplished by ELISA assays using type VII collagen, the EBA antigen (discussed in Chapter 60). Immunoelectron microscopy also distinguishes these diseases because the IgG in EBA is below the lamina densa on the anchoring fibrils (type VII collagen), whereas the IgG in bullous pemphigoid is closely associated with the basal cell hemidesmosomes.180

SUBEPIDERMAL BLISTERING DISEASES WITH AUTOANTIBODIES

|

SUBEPIDERMAL BLISTERING DISEASES WITHOUT AUTOANTIBODIES

|

INTRAEPIDERMAL BLISTERING DISEASES WITH AUTOANTIBODIES

|

INTRAEPIDERMAL BLISTERING DISEASES WITHOUT AUTOANTIBODIES

|

As opposed to bullous pemphigoid, cicatricial pemphigoid usually presents with mucosal lesions predominantly, if not exclusively (see Chapter 57). Cicatricial pemphigoid is characterized by desquamative gingivitis as well as inflammation and scarring of conjunctiva. If there is blistering of the skin, it may be transient and may result in scarring. Large, tense blisters, which are characteristic of bullous pemphigoid, are usually not seen in cicatricial pemphigoid.

Complications

Prognosis/Clinical Course

Bullous pemphigoid is characterized by a waxing and waning course with occasional spontaneous remission in the absence of treatment. Localized disease often resolves spontaneously, but spontaneous remission can even occur in patients with more generalized disease. For example, prior to the availability of systemic corticosteroids, Lever reported that 8 of 30 adults with bullous pemphigoid went into remission after approximately 15 months (range, 3–38 months) of active disease.110 In treated patients, the length of disease ranges from 9 weeks to 17 years with a median treatment period of 2 years and 50% remission rates in patients followed for at least 3 years.181 Clinical remission with reversion of direct and indirect IF to negative has been noted in patients, even those with severe generalized disease, treated with oral corticosteroids alone or with azathioprine.162,182 High ELISA titers and, to a lesser degree, positive direct IF at the time of therapy cessation has been associated with a high risk of relapse within the first year following cessation of therapy.182 At least one of these tests should be performed before therapy is discontinued.

Old age, poor general health, and the presence of anti-BP180 antibodies have been associated with a poor prognosis.183–186 Early mortality rates in untreated patients were reported to be 25%.110 Newer studies have shown the 1-year mortality of patients with bullous pemphigoid to be between 19% and 40% in Europe, but lower (less than 6%–12%) in the United States.12,183–185,187–190 The factors underlying this discrepancy in mortality rates between Europe and the United States are not clear. While mortality rates remain relatively low in the United States, recent studies have confirmed a slow steady increase in mortality over the last 24 years in the United States.191

Treatment

Treatment of bullous pemphigoid depends greatly on the extent of disease. Localized bullous pemphigoid often can be treated successfully with topical corticosteroids alone (Box 56-2).162,166,192

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree