Key points

- •

Botulinum neurotoxin type A produces chemodenervation of muscle by preventing binding of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular endplate.

- •

Relaxation of the underlying muscle improves rhytids and can alter facial shape by changing the balance between muscles.

- •

Injection requires an appreciation of underlying anatomy.

- •

Results depend on a balance between function and aesthetics.

- •

Side-effects are easily recognized and temporary.

- •

Patient selection and proper technique are key to producing consistent results.

Patient selection

Botulinum type A neurotoxin (Botox® Cosmetic) is a potent agent, specifically used to target mimetic muscles of facial expression for aesthetic change. The resultant physiologic denervation eliminates muscle pull on the skin and temporarily reduces the appearance of dynamic lines of facial expression. Botox® Cosmetic therapy has evolved from primarily a ‘wrinkle treatment’ to a method of targeted modulation of facial dynamics. By disrupting the balance of agonist–antagonist muscle groups, facial expression can be subtly manipulated in a precise and predictable way.

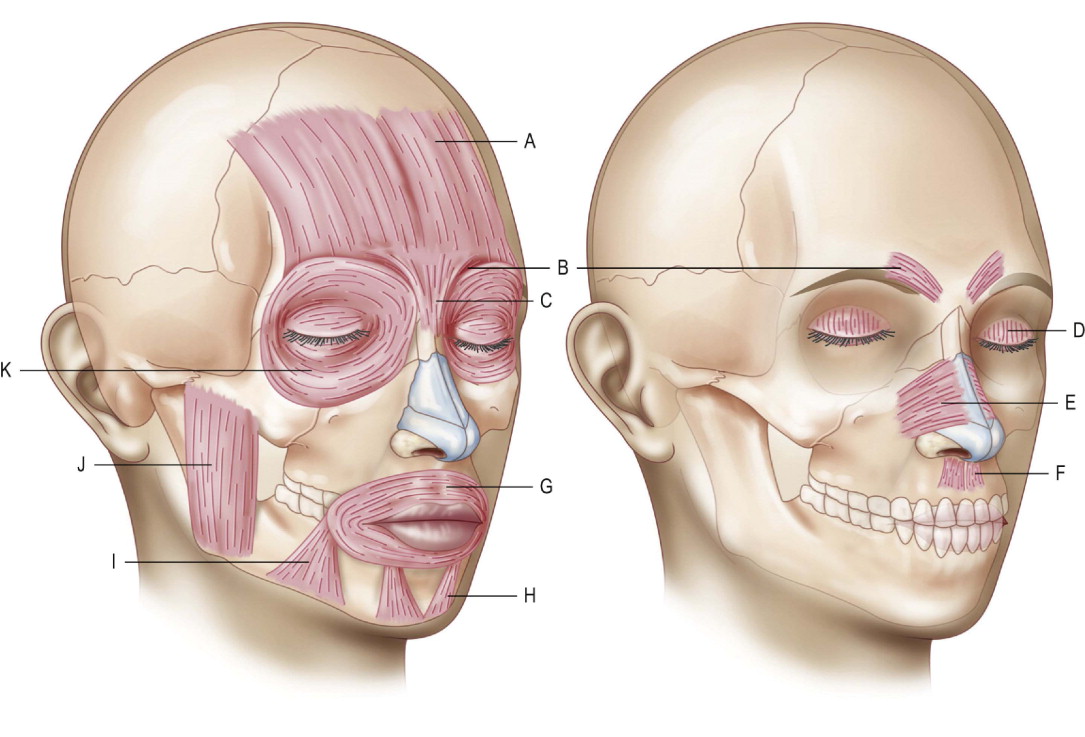

The use of Botox® Cosmetic requires a basic understanding of the chemodenervation process and a comprehensive understanding of functional facial anatomy ( Figure 1.1 ). There are seven serotypes of Botulinum toxin (A, B, C, D, E, F and G) produced by the obligate anaerobic bacterium Clostridium botulinum . Of these subtypes, type A is the most toxic and also the most widely used. Available under the trade names Botox® Cosmetic (Allergan, Irvine, CA) and Reloxin® (Medicis, Scottsdale, CA), the use of Type A toxin has grown to be the most common non-surgical procedure performed by plastic surgeons. Indeed, since the FDA approval of Botox® Cosmetic in 2002 to treat glabellar lines, Botox® Cosmetic injections have become more common than the top five surgical procedures combined. In 2007, as reported by the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, total liposuction (456,828), breast augmentation (399,440), blepharoplasty (240,763), abdominoplasty (185,335), and breast reduction (153,087) procedures add up to 1,435,453 total procedures. This is almost half of the total number of Botox® Cosmetic injections (2,775,176) performed during the same time period.

Type B toxin, marketed as Myobloc (Elan Pharmaceuticals, San Francisco, CA) is also used medically for non-aesthetic indications. Despite the unique biochemical and neurophysiological properties of each serotype, the fundamental mechanism of selective blockage of acetylcholine release at the pre-synaptic side of the motor endplate is shared. This results in the disruption of nerve transmission and, therefore, in a weakening or paralysis of muscle contraction. Consequently, when selecting a patient for Botox® Cosmetic, one must understand the underlying basis for the patient’s concern (muscle action) and ensure that the external appearance is not due to some other cause (i.e., static lines, dermal atrophy).

Many facial changes associated with the aging face can be attributed to the underlying muscular activity, muscle hypertrophy, and patterns of facial expression for which Botox® Cosmetic is an appropriate method of treatment. However, aging also leads to loss of skin elasticity and changing collagen composition, which results in loosening of dermal support mechanisms. The loss of subcutaneous fat and pull of gravity leads to progressive ptosis of facial skin and soft tissue, which can be accentuated by Botox® Cosmetic. Botox® Cosmetic, therefore, should not be viewed as an anti-aging therapeutic per se, but rather as a way to achieve a balance between hyperactive muscle and maintenance of facial expression.

Indications

It is often suggested that the spectrum of facial rejuvenation involves resurfacing, replacing, redraping, repositioning, recontouring, removing, and relaxing. Botox® Cosmetic is the fundamental key to muscle relaxation. Specific patient characteristics and anatomic features help to define good or conversely less acceptable candidates for Botox® Cosmetic injections ( Table 1.1 ). The patient, as well as the physician, must understand the basic reasoning for Botox® Cosmetic use:

- •

The patient should have a good understanding of the cause of his or her ‘disagreeable biologic condition’ and the role of Botox® Cosmetic in ameliorating it.

- •

The patient should be aware of Botox® Cosmetic’s chemo-neuromuscular paralysis in addressing hyperkinetic muscles of facial expression.

- •

The patient should have isolated defects that are not necessarily the result of overlapping conditions (i.e., dermal or subcutaneous fat atrophy, excess skin), in addition to the rhytid.

| Aesthetic | Reconstructive |

|---|---|

|

|

Botox® Cosmetic is a safe and effective therapy for most patients. The contraindications are few, but must be carefully considered ( Box 1.1 ). Botox® Cosmetic should be carefully considered in patients with underlying coagulopathies (i.e., thrombocytopenia, hemophilia, or those receiving antigoagulation therapies). Additionally, patients with certain neuromuscular disorders such as ALS, myasthenia gravis, or Lambert-Eaton syndrome may be at increased risk of serious side-effects. Special consideration should also be used in treating the problem patient, since the results from Botox® Cosmetic are dramatic and require understanding and co-operation by the patient.

Hypersensitivity to ingredients

Albumin, sodium chloride, botulinum toxin

Presence of infection at the injection site

Neuromuscular disease

Myasthenia gravis, Eaton–Lambert syndrome, motor neuron disease

Drugs that interfere with neuromuscular transmission

Antibiotics (certain aminoglycosides, lincosamides, polymixins), penicillamine, quinine, calcium channel blockers, neuromuscular blocking agents (atracurium, succinylcholine), anticholinesterases, magnesium sulfate, and quinidine

All may increase the paralytic effect of the toxin

Pregnancy/lactation

Patients on anticoagulation therapy/aspirin (relative contraindication)

Inappropriate anatomy

Skin laxity, photo-damage

Poor psychological adjustment / unrealistic expectations

The original studies leading to the approval of Botox® Cosmetic Cosmetic by the FDA in 2002 for glabellar furrows were for patients less than 65 years old. All other cosmetic indications other than hyperhydrosis are considered ‘off label’. However, as experience is gained in the alternation of facial dynamics, the aesthetic indications have expanded to include male and female adults of all ages. Additionally, the focus has shifted from complete paralysis of mimetic muscles to manipulation of agonist–antagonist muscle groups to enhance facial balance and shape. The ideal balance is different in patients of varying ages, and between men and women. Adjustments in Botox® Cosmetic dose and location of injection should be made accordingly. Additionally, the safety and efficacy of Botox® Cosmetic in patients more than 65 years old and younger than 18 years old has not been specifically determined. However, age per se is not a strict contraindication to Botox® Cosmetic. Currently, the safety and efficacy of Botox® Cosmetic have not been established in the pediatric and adolescent population. However, Botox® Cosmetic is used in the pediatric population for non-cosmetic indications at much higher doses than typically used in adults.

Careful patient selection and counseling are important as with most elective cosmetic procedures. Patient satisfaction is often determined by this. Patients who are ill prepared for the paralytic effect and changes in facial morphology can experience untoward psychological adjustment following therapy ( Box 1.2 ). With the expansion of direct patient marketing and self-directed ‘education’ from the World Wide Web, it is even more important to carefully discern patient expectations prior to treatment.

|

|

For many reasons, we do not recommend the use of Botox® Cosmetic in non-medical settings such as health clubs, a person’s home, or a ‘party’ atmosphere as, in the event of an emergency, the proper equipment is unlikely to be available. Outside the office it is unlikely that proper medical record keeping will be performed. A ‘party’ atmosphere with alcohol and extraneous influences like peer pressure is not the setting to obtain informed consent or perform a medical procedure. Proper follow-up is in question and there is the potential for failure to discuss other options and treatments that may be more appropriate. The treatment itself is also trivialized by the unprofessional setting. Finally, should medico-legal issues arise from treatment in a non-medical setting the practitioner would be in a severely compromised position to defend himself or herself.

Operative technique

Pre-operative preparation

Patient education

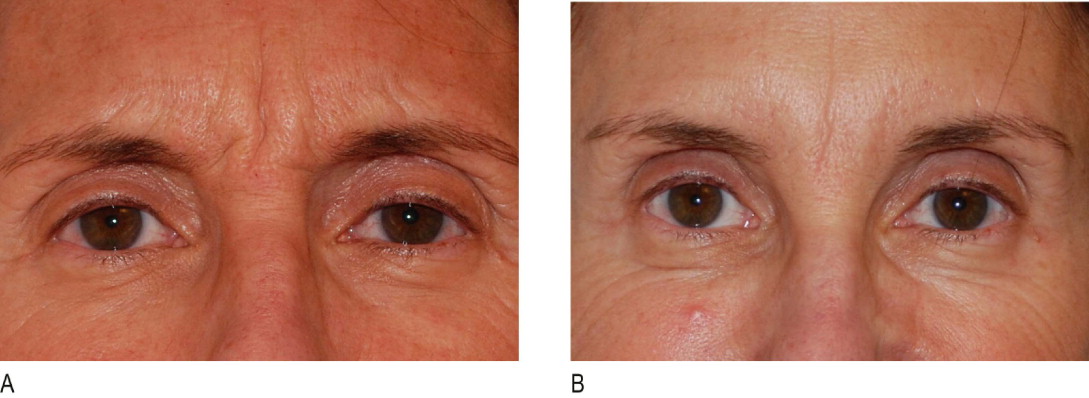

The patient is interviewed by a staff member and given an information pack to review prior to the consultation with the physician. Many patients have been referred by friends who have had previous Botox® Cosmetic injections and they have extensively searched the internet prior to their appointment. Therefore, much of the education involves deciphering what the patient believes to be accurate and rectifying any misconceptions. For example, the mechanism of action of Botox® Cosmetic is relaxation of the underlying muscle and release of the overlying skin. If the rhytid persists due to dermal atrophy, then a filler is necessary – this is the most common circumstance whereby patients believe that Botox® Cosmetic did not work ( Figure 1.2 ). Additionally, treatment of the lateral brow presents a compromise between complete paralysis of the frontalis and elimination of all suprabrow rhytids (which may lead to brow ptosis) or partial maintenance of frontalis activity with incomplete elimination of all suprabrow rhytids ( Figure 1.3 ). Indeed, this area is discussed at every visit with patients requesting frontalis muscle treatment.

Medical history

The patient is questioned about prior treatments with topical agents or filler materials, and aesthetic surgical procedures. The patient is also questioned about previous Botox® Cosmetic use, location of injection, dosage, response to treatment and satisfaction. Prior surgical history, as well as injectable-filler use is important as these may alter underlying anatomy. Patients often remember where the Botox® Cosmetic and fillers were injected, but often have no idea about the type of filler or number of units of Botox® Cosmetic injected.

Physical examination

The patient is asked to actively contract the intended muscle of treatment in front of a hand mirror ( Figure 1.4 ). This identifies the muscle and also serves as a tool for patient education by locating the rhytid. The patient is instructed to accentuate the specific facial lines to be treated by frowning (glabellar lines), squinting (lateral canthal lines), elevating the brow (horizontal forehead lines), grimacing (platysma bands) and pursing the lips (vertical lip lines). Patients never scrutinize their faces as much before a procedure as they do after it has been completed; therefore it is important to identify and alert patients to naturally occurring asymmetries and any other germane features that are present before treatment. For example, there can be more aging on the left side of the face in general and, in particular, crow’s feet because of exposure to the elements while a person is seated on the driver’s side of an automobile. Additionally, a person’s natural tendency to activate certain muscles may lead to asymmetric facial rhytids. Dose and location of toxin injection may need to be adjusted to compensate for this imbalance. The dose of Botox® Cosmetic can be generalized; it is best, however, to individualize it based on gender, prior history location, muscle mass and intended benefit. Additionally, coexisting conditions in the field of treatment that will not be improved with Botox® Cosmetic (i.e., loose skin in the neck; static lines in the periocular region) or may actually worsen should be identified and discussed with the patient. Pre-operative photographs and/or video can be an invaluable resource for post-treatment discussions with the patient and to guide future therapy.

The patient should then be examined for pre-existing ptosis. There are variations of ptosis that can be encountered before and after treatment ( Table 1.2 ). One must distinguish between: 1) Drug-induced eyelid ptosis (diffusion to leavator muscle), 2) Pre-existing eyelid ptosis (compensated for by frontalis muscle hyperactivity), and 3) True brow ptosis (pseudo eyelid ptosis, which occurs after the frontalis muscle is relaxed) ( Figure 1.5 ). Interestingly, ophthalmologists report that attempts to create ptosis by direct levator injection are unreliable. The combination of some form of lateral brow stabilization, such as the lateral brow lift, before, concurrently or after Botox® Cosmetic treatment allows for unmitigated Botox® Cosmetic treatment without the risk of brow ptosis ( Figure 1.6 ).