Body Image and Plastic Surgery

Thomas F. Cash PhD

The psychology of physical appearance may be approached from two different perspectives—the “outside, body-in-society view” and the “inside, body-in-self view” (1). The first perspective considers how certain aspects of human appearance, such as physical attractiveness, weight, height, body shape, hair color, etc., affect interpersonal perceptions, cognitions, and behaviors. As Sarwer and Magee reviewed in the previous chapter, behavioral scientists have systematically studied appearance stereotyping and whether people who differ with regard to particular physical characteristics receive different social reactions and outcomes (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Whether due to bioevolutionary “pre-wiring,” cultural socialization, or people’s interactions with each other, there is little doubt that physical appearance can exert both subtle and profound effects on human relations, from infancy to old age, and from the bedroom to the boardroom.

The second perspective is the body-in-self view of one’s appearance, which essentially defines “body image” (6, 7, 8). Body image refers to the person’s own experiences of embodiment, especially self-perceptions and self-attitudes toward one’s appearance. Psychological scientists have investigated how body image develops, what physical and psychosocial factors shape this development, and, in turn, how body image affects other facets of the individual’s functioning. People’s experiences of their own appearance are often quite different from how others see and evaluate them. Good looks do not guarantee a subjectively positive body image nor is a plain or homely appearance necessarily associated with a problematic body image.

Plastic surgeons work at the intersection of these two perspectives on human appearance. With precision and skill, they alter and sometimes transform outward physical appearance—refining, reshaping, rejuvenating, restoring, or reconstructing to create an external change that looks “better,” “more attractive,” or “normal.” At the same time, surgeons understand that it is the patient’s perceptions and attitudes toward this change that will ultimately determine the outcome. Indeed, Edgerton has maintained that “Although aesthetic or cosmetic surgery is undertaken to improve the patient’s appearance, the purpose of aesthetic surgery is to facilitate positive psychological changes. In fact, the only rationale for performing aesthetic plastic surgery is to improve the patient’s psychological well being” (9). For most cosmetic surgery patients this desired improvement is specifically focused on body image but not necessarily on other aspects of psychosocial quality of life. That is, most cosmetic surgery patients seek to feel more positively about specific aspects of their appearance, but likely are not seeking to change, via surgery, broader aspects of their life. For others, however, the desired changes may be even more pervasive (e.g., to change one’s overall self-concept). And, of course, a small minority of people look to cosmetic surgery for a “life transformation”—more often than not, a misguided and ineffective solution to their unhappiness.

Body image is central to plastic surgery, as nearly every chapter in this volume articulates. The extensive research on cosmetic surgery by Sarwer and colleagues has

advanced the field considerably, moving us from an early era of unscientific and biased inquiry to a more sophisticated scrutiny of the motives for, and outcomes of, specific cosmetic procedures, armed with a contemporary conceptual framework and improved research methodology (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Moreover, body image research has become increasingly relevant to reconstructive surgery for both congenital and acquired disfigurements (16, 17, 18, 19).

advanced the field considerably, moving us from an early era of unscientific and biased inquiry to a more sophisticated scrutiny of the motives for, and outcomes of, specific cosmetic procedures, armed with a contemporary conceptual framework and improved research methodology (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Moreover, body image research has become increasingly relevant to reconstructive surgery for both congenital and acquired disfigurements (16, 17, 18, 19).

The primary aim of this chapter is to clarify the meaning and importance of the multiple dimensions that define body image and, ultimately, its relationship to plastic surgery. The chapter provides a conceptual framework that organizes these dimensions and delineates their causal development as well as their consequences. It also identifies some of the best methods to measure these various aspects of body image, particularly among plastic surgery patients. The chapter concludes with the discussion of an empirically supported psychosocial approach to body image change, one that may be helpful as an adjunct or alternative to plastic surgical procedures. All facets of this chapter will inform the plastic surgeon about crucial issues in understanding body image.

A BRIEF HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF BODY IMAGE

The study of body image, or “body schema,” originated at the turn of the 20th century as physicians sought to understand the causes of certain neurological patients’ strange bodily sensations, including such phenomena as “phantom limb,” “autotopagnosia,” “hemiasomatognosia,” and “anosognosia” (20). From 1914 to 1940, Schilder broadened the focus from neuropathology to the attitudes and feelings patients had about their bodies. At the same time, psychoanalytic professionals expanded Freud’s psychosexual theory to understand patients’ perceptions of the body as the “boundary” between themselves and their external world (21), a boundary that takes on meaning especially with respect to one’s largely unconscious feelings about the self. Subsequently, Fisher dedicated much of his career as a psychologist to the investigation of body image from a psychoanalytic viewpoint, publishing prolifically on the “body boundary” construct (21, 22, 23) Shontz (24) was critical of this psychodynamic perspective, drawing from his integration of theory and data from several areas of experimental psychology. He conceptualized body experience as multidimensional, and he applied research findings to understand and help individuals with physical disabilities (25).

Over the past several decades, clinical and empirical interests in body image have flourished, largely in response to the increasing prevalence of, and interest in, eating disorders. Numerous new assessments of body image have emerged and scientific knowledge has expanded (7, 8,26, 27, 28). Despite these advances, such research has fostered a limited, perhaps myopic, view of body image (29, 30). Body image and its measurement have focused intensively on weight/shape concerns among women and girls. The publication of body image research has been scattered across a range of scientific journals. A complete understanding of human experiences of embodiment must transcend so narrow a vision.

Cash and Pruzinsky (7) have argued that the future of body image scholarship lies at the interface of behavioral and medical/health sciences. In their edited volume, Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice, there are eight chapters devoted to understanding body image issues in the specialties of dermatology (31), dental medicine (32), obstetrics and gynecology (33), urology (34), endocrinology (35), oncology (36), and rehabilitation medicine (37), as well as body image issues among persons with HIV/AIDS (38). Moreover, several chapters examine body image and its changes via cosmetic (11) and reconstructive surgery (16, 17, 18). As the volume’s contents further attest, important developments are occurring in the prevention of body image problems, the growing recognition of body image issues

among boys and men, and greater attention to the cultural and ethnic diversity of body images. Indeed, these themes are reflected in the mission of a new peerreviewed scientific journal, Body Image: An International Journal of Research, that commenced publication in 2004. This journal is founded on the proposition that experiences and conditions of embodiment have far-reaching implications for human development and the quality of life.

among boys and men, and greater attention to the cultural and ethnic diversity of body images. Indeed, these themes are reflected in the mission of a new peerreviewed scientific journal, Body Image: An International Journal of Research, that commenced publication in 2004. This journal is founded on the proposition that experiences and conditions of embodiment have far-reaching implications for human development and the quality of life.

DEFINING AND ASSESSING BODY IMAGE: CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES

Body image is now typically viewed as a multidimensional construct consisting of two overarching components: perceptions and attitudes (6, 7, 8). The perceptual component of body image pertains to the extent to which a person is able to judge his or her appearance accurately on some physical dimension, usually body size. Researchers have developed instruments to assess individuals’ degree of body-size distortion, whether based on perceptions of the whole body or discrete areas of the body (8,39, 40). These methods range from simple figural stimuli (e.g., silhouettes) to more elaborate video technologies whereby persons adjust projected images of their own body to convey their body perceptions. However, among various scientific shortcomings of these perceptual assessments, they usually neglect self-perceived attributes of specific body features (e.g., facial characteristics, height, hair, muscularity, etc.).

Body image attitudes consist of individuals’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to their physical appearance. These attitudes are typically assessed by self-report questionnaires. Thompson et al. (8,41) provide an extensive listing of these instruments. Body image attitudes themselves are multidimensional, comprised of body-image evaluation/affect and body image investment. Body-image evaluation refers to one’s level of body satisfaction or dissatisfaction and evaluative thoughts or beliefs about one’s body (e.g., appearance). The degree of body satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) depends on the degree of congruence (or discrepancy) between self-views of the body or body parts and one’s personal physical ideals. The Body-Image Ideals Questionnaire is one tool that assesses this self-ideal discrepancy dimension of the construct (42, 43). Other examples of well-validated and widely used measures of body satisfaction pertinent to plastic surgery include the Body Esteem Scale (44) and the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire-Appearance Scales (MBSRQ-AS), which contains multiple subscales to measure particular attitudes toward one’s appearance (45, 46, 47). Questionnaire 4-1 provides two of these MBSRQ scales—the Appearance Evaluation Scale has seven items and the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale has nine items.

Associated with these evaluations is body image affect, which refers to the emotional experiences that result from one’s body image appraisals. For example, when a person evaluates his or her appearance unfavorably in some particular context, dysphoric emotions (e.g., anxiety, disgust, or shame) may result. The Situational Inventory of Body-Image Dysphoria (48) measures how often individuals experience negative body-image emotions in each of 20 situations (e.g., looking in the mirror, exercising, interacting with attractive people, etc.). This measure may be useful with plastic surgery patients, as it provides an assessment of negative emotional experiences across a range of interpersonal and other situations.

The attitudinal dimension of body-image investment refers to the extent to which one’s attention, thoughts, and actions focus on one’s looks, including the extent of reliance on physical appearance as a criterion for defining one’s sense of self. Examples of measures of this facet of body image include the Appearance Orientation subscale of the MBSRQ-AS (46) and the Appearance Schemas Inventory-Revised (ASI-R) (49). The ASI-R assesses two somewhat different aspects of body image investment. The first aspect, self-evaluative salience, reflects the extent to which people

define themselves by their physical appearance. The second aspect, motivational salience, refers to how much individuals attend to their appearance and engage in appearance-management behaviors. Self-evaluative salience constitutes a more pathogenic type of body image investment, because one’s looks dictate one’s self-worth. Motivational salience, on the other hand, is not inherently problematic, as it mostly entails taking care of or pride in one’s appearance (49). In a recent study of 214 college women (50), those who were most invested in their appearance were most favorably predisposed toward cosmetic surgery. The relationship was stronger for self-evaluative salience than for motivational salience.

define themselves by their physical appearance. The second aspect, motivational salience, refers to how much individuals attend to their appearance and engage in appearance-management behaviors. Self-evaluative salience constitutes a more pathogenic type of body image investment, because one’s looks dictate one’s self-worth. Motivational salience, on the other hand, is not inherently problematic, as it mostly entails taking care of or pride in one’s appearance (49). In a recent study of 214 college women (50), those who were most invested in their appearance were most favorably predisposed toward cosmetic surgery. The relationship was stronger for self-evaluative salience than for motivational salience.

The Epidemiology of Body Image Discontent

Large sample surveys confirm that body image dissatisfaction is fairly commonplace in America. From a national Psychology Today magazine survey using the MBSRQ-AS, Cash et al. (51) sampled 2,000 individuals to represent the United States population, stratified by age and gender distributions. The results revealed that 38% of women and 34% of men were dissatisfied with their appearance in general. Although most respondents were content with their face and height, their body weight and middle torso were the foci of body dissatisfaction for most men and women. A representative survey of American women in 1993 (52) found that 48% of respondents were dissatisfied with their appearance, as well as, preoccupied with being or becoming overweight. A Psychology Today survey published in 1997 (53) revealed that 56% of the women and 43% of the men evaluated their overall appearance negatively, suggesting a possible increase in body image dissatisfaction across the population. Although such survey results are quite interesting, methodological problems particularly with the magazine surveys, including possible sample self-selection biases and the non-comparability of questions across the various studies, may have inflated dissatisfaction rates in the most recent survey data (54). Still, there is little doubt that a sizeable percentage of women and men find aspects of their physical appearance to be unacceptable.

A meta-analysis of 222 body-image studies from the past 50 years found a widening gender gap in body image, with continual increases in women’s discontent (55). However, several recent studies suggest that, at least among college women, rates of body image dissatisfaction may have leveled off or actually declined in the past few years, despite their increase in body weight (56). Although numerous studies confirm significant gender differences in body satisfaction, differences extend beyond evaluative body image. For example, Muth and Cash (57) investigated body image evaluation, affect, and investment among college women and men. Relative to men, women reported greater self-ideal discrepancies, frequent negative body image emotions, and more cognitive and behavioral investment in their physical appearance. Thus, dissatisfaction with, and distress about, their looks are more common among women, who are also more invested in their appearance as a source of self-definition. Furthermore, gender differences in body image evaluation seem to be greatest during adolescence and early adulthood, when females are especially vulnerable to body image disturbances (55,58). Although Garner (53) did not observe greater discontent among young people in his 1996 survey, he noted the curious fact that with increasing body weight among older groups, women’s body dissatisfaction did not worsen. Moreover, among cosmetic surgery patients, older women interested in rhytidectomy and/or blepharoplasty reported less dissatisfaction with their facial appearance as compared to younger women interested in rhinoplasty (59). Perhaps aging brings a shift in values and a more secure identity that facilitates divestment of youthful appearance standards (60, 61).

Currently, there is a growing interest in male body image, especially in relation to issues concerning the cultural idealization of muscularity (62, 63, 64, 65). (Chapter 15 discusses the relationship between muscularity and body contouring procedures.) Male cosmetic surgery patients, as compared to female patients, reported less investment

in their appearance (as assessed by the Appearance Orientation scale of the MBSRQ-AS) but otherwise did not differ in their body image concerns (66).

in their appearance (as assessed by the Appearance Orientation scale of the MBSRQ-AS) but otherwise did not differ in their body image concerns (66).

In addition to age and gender differences, ethnicity is relevant to body satisfaction. In general, even at higher body weights African-American women hold more favorable body image evaluations than do European-American or Hispanic-American women (52,67). Because a thin female body size is idealized less within African-American culture, these women of color may experience less of a self-ideal discrepancy, even at heavier body weights (68, 69). Relative to European-American women, they also have a higher threshold for perceiving a body as “fat” (68). Increasingly, researchers are also recognizing that there is substantial diversity of body image experiences within ethnic groups (67,70, 71).

Body image experiences may also differ due to sexual orientation. However, the research findings are somewhat clearer for men than for women. Morrison et al. (72) conducted a meta-analysis of 27 extant body image studies that compared heterosexual and homosexual men and women. On average, gay men reported less body satisfaction relative to heterosexual men, whereas lesbian and heterosexual women’s body images did not differ, except in those studies in which the two groups were comparable in body mass. In the latter research, lesbian participants expressed a more favorable body image evaluation. In many studies, lesbians have been found to be significantly heavier than heterosexual women (72, 73), and this weight disparity may mask women’s sexual orientation differences in body image. Most research on body image and sexual orientation has examined the evaluative aspect of body image, yet ignored body image investment. A few published studies have observed higher levels of appearance investment among gay men relative to heterosexual men (74, 75, 76).

In summary, contemporary researchers recognize that body image is truly multidimensional; it is not “one thing.” Accordingly, numerous psychological assessment techniques have been developed to measure these various facets of body image. Such advances have enabled scientists and clinicians to understand body image with more precision and to elucidate many contributions to individual differences in body image experiences, such as gender, age, ethnicity, and sexual orientation.

BODY IMAGE: HISTORICAL AND DEVELOPMENT DETERMINANTS

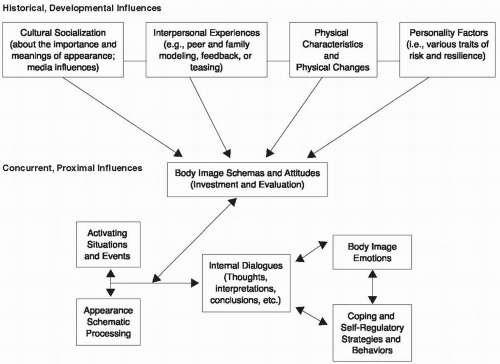

According to a cognitive social learning perspective, body image develops as a complex function of various historical and concurrent influences (77, 78, 79, 80, 81). Figure 4-1 summarizes this model for understanding body image development and its operation in everyday life. Historical factors refer to past events, attributes, and experiences as well as developmental processes that shape how people come to think, feel, and behave with regard to their physical appearance. These historical/developmental determinants fall into several categories: (i) cultural socialization about the importance and meanings of human physical appearance and one’s own body; (ii) interpersonal experiences (including both familial and peer influences), especially experiences during childhood and adolescence; (iii) actual physical characteristics and developmental changes in these attributes; and (iv) personality variables that affect how the individual construes his or her body. As a result of these influences, individuals acquire basic body image attitudes that, in turn, serve to predispose how they attend to, perceive, interpret, and react to current life events.

Several recent volumes have discussed the growing research evidence on these historical influences (7, 8,28,81, 82). A brief overview of the key findings is presented here.

Cultural Media Forces

As Sarwer and Magee noted in the previous chapter, Western culture’s emphasis on beauty and thinness as standards for women permeates all levels of mass media

(8,83, 84). The widespread dissemination of these cultural expectations fuels the drive for the “ideal female shape” in girls and women. This quest to achieve the societal standard is so common that it has been referred to as a “normative” process (85) even prior to the explosion in cosmetic surgery within the past decade. The internalization of these extreme standards puts females at risk for body image and eating disorders, as well as a host of other psychosocial problems (86, 87, 88). The media messages have multiple effects—transmitting the cultural appearance ideal for individual internalization, highlighting the importance of human appearance (the power and necessity of attractiveness), and provoking personal comparisons with these standards in everyday life (potentially inducing recurrent body image dysphoria).

(8,83, 84). The widespread dissemination of these cultural expectations fuels the drive for the “ideal female shape” in girls and women. This quest to achieve the societal standard is so common that it has been referred to as a “normative” process (85) even prior to the explosion in cosmetic surgery within the past decade. The internalization of these extreme standards puts females at risk for body image and eating disorders, as well as a host of other psychosocial problems (86, 87, 88). The media messages have multiple effects—transmitting the cultural appearance ideal for individual internalization, highlighting the importance of human appearance (the power and necessity of attractiveness), and provoking personal comparisons with these standards in everyday life (potentially inducing recurrent body image dysphoria).

Males do not escape the media’s messages about the meaning and ideal of the male body—tall, handsome, lean, broad shouldered, and powerfully muscular. Researchers are beginning to recognize the importance of these cultural images to male body image development (62,65,89). Adoption of these extreme images (such as those seen among professional bodybuilders or wrestlers as well as unrealistically mesomorphic action figure toys) as personal body image ideals may set up the male for body dissatisfaction.

Familial Influences

Expectations, opinions, and verbal or nonverbal messages within the family also influence the formation of body image attitudes (90). Parental modeling conveys the extent to which physical appearance is valued within the family, establishing a

yardstick by which the child measures himself or herself. For example, highly appearance-invested mothers who value and engage in dieting behavior or instigate family competition based on physical attractiveness may promote a negative body image in their daughters (91, 92, 93). The attractiveness of one’s siblings may also affect body image development. Having a more attractive sibling may contribute to a less favorable body image, just as having a less attractive sibling may have the opposite effect (91). Siblings, especially brothers, are frequent perpetrators of appearance-related teasing (91,94). Thus, family members are powerful agents of socialization about the meaning and acceptability of one’s physical characteristics.

yardstick by which the child measures himself or herself. For example, highly appearance-invested mothers who value and engage in dieting behavior or instigate family competition based on physical attractiveness may promote a negative body image in their daughters (91, 92, 93). The attractiveness of one’s siblings may also affect body image development. Having a more attractive sibling may contribute to a less favorable body image, just as having a less attractive sibling may have the opposite effect (91). Siblings, especially brothers, are frequent perpetrators of appearance-related teasing (91,94). Thus, family members are powerful agents of socialization about the meaning and acceptability of one’s physical characteristics.

Peer Influences

As every parent knows, children’s peer groups can be very influential on the development of personal values and sense of self. Peers model and reinforce conformity to certain appearance standards, such as what clothing and hairstyles are most desirable. Friendship cliques may also reinforce conformity to group norms about appearance standards and behaviors. For example, research has confirmed greater similarities within such groups of girls on body image concerns and eating/dieting behaviors (95).

Appearance teasing is a common occurrence in childhood and adolescence, and such interpersonal ridicule by peers clearly predisposes body dissatisfaction (96). The child comes to learn that his or her body is an enemy of social acceptance. Correlational evidence confirms a relationship between prior appearance teasing and greater body dissatisfaction in adolescence and adulthood (8,51,91,94,97). Such experiences may play a causal role in faulty body image development (98, 99). In addition to teasing, explicit or subtle criticisms about one’s appearance may be seen as feedback that one’s looks are socially unacceptable (91). A history of appearance-related teasing has differentiated women seeking breast augmentation surgery from similarly small-breasted women not interested in surgery (100).

Romantic Relationships

Physical attractiveness exerts a powerful influence on processes of dating and mating (3, 4). However, there has been little research on how body image is affected interpersonally in romantic relationships (96). How one believes one’s looks “measure up” to a partner’s expectations is an important predictor of one’s own body satisfaction (43,101). Of course, sometimes these beliefs about how the partner feels about one’s body are merely projections of one’s own body image feelings (102). Nevertheless, a more positive body image is associated with having a partner who accepts and compliments one’s appearance, and a more negative body image if the partner is critical and demeaning (102).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree