Fig. 29.1

The transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap with its two pedicles

Although currently I use the procedure only in very select cases, it is able to provide the surgeon with an excellent amount of well-perfused abdominal tissue comparable only to techniques using free flap transfer.

29.2 Indications

Its principal indication is to increase the circulation to the abdominal flap; therefore, the blood supply can be doubled and complications such as fat or cutaneous necrosis can be essentially minimized.

Maneuvers to improve the flap perfusion are used for patients with risk factors that can impair the perfect blood supply to the abdomen.

The most relevant risk factors are smoking, obesity, previous abdominal surgery, radiotherapy, and existence of systemic disease (diabetes, hypertension) [9] (Fig. 29.2).

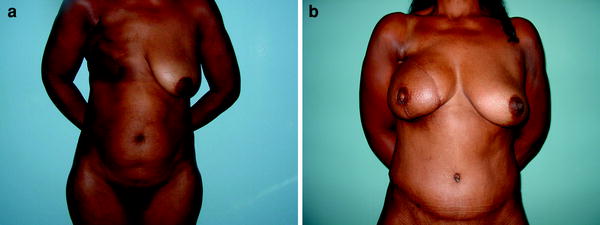

Fig. 29.2

Preoperative (a) and postoperative (b) delayed reconstruction on a patient with visible damage after radiotherapy. The bipedicled TRAM flap was a suitable option a with good outcome

29.3 Free Flap or Bipedicled TRAM Flap?

The apologists for the use of microsurgical technique to transfer the abdominal tissue for breast reconstruction (free TRAM flap, muscle sparing flap, deep inferior epigastric perforator, DIEP, flap) are extremely emphatic when describing its many advantages.

The main one is the unquestionable better blood supply, once the flap nutrition is provided by the inferior epigastric system (it is the primary blood supply to the lower abdominal skin and subcutaneous fat). The second one relates to the significant abdominal wall injury caused by the bilateral flap harvesting [10].

However, the free flap transfer demands especial skills of trained surgeons and nurses. The full control of the technique also depends on specialized staff to closely evaluate the patient during the postoperative period. Operating in a center where the patient can be safely taken to the operating room anytime for an urgent revision is also mandatory.

29.4 The Abdominal Wall Issue

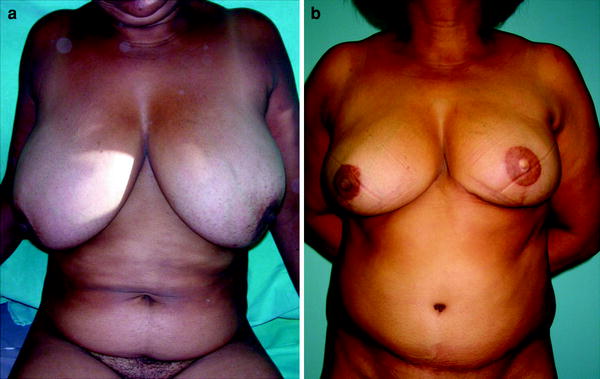

It has been widely recognized that a unilateral or bilateral pedicled TRAM flap can lead to a considerable reduction of the abdominal strength (Fig. 29.3). Many publications on this subject witness the discomfort of authors with this topic.

Fig. 29.3

Bulges and true hernias are more frequent with the bipedicled TRAM flap technique

An early study published by Hartrampf and Bennet [11] showed that the postoperative assessment of 300 women after bilateral harvesting resulted in a remarkable decrease of the abdominal strength, represented by an incapacity to perform sit-ups.

Also Petit et al. [12] in evaluating unilateral and bilateral pedicled TRAM flaps in 38 patients showed that 50 % of the single-pedicle transfers caused important impairment of the upper portion of the rectus and oblique muscles opposed to 60 % of the double-pedicle series.

The muscle-sparing technique (transferring only the central portion of the muscle, which contains the vessels) based on the work of Mizgala et al. [13] has not proved the expected efficiency in reducing the morbidity to the abdominal wall of the classic pedicled TRAM flap, unilateral or bilateral. On the other hand, splitting the muscle in pedicled flaps remains controversial and some surgeons [14] emphatically avoid doing this because of the vascular pattern of the epigastric system (choke vessels connect the superior and the inferior systems), where superficial to the rectus muscle an important net of arteries and veins can be injured during muscular division.

Finally, a recent study by Chun et al. [15] suggests there is no significant difference in donor site morbidity, functional outcomes and patient satisfaction when bipedicled TRAM or DIEP flaps are use din breast reconstruction, concluding that the technique remains a good choice for many patients who will undergo postmastectomy breast reconstruction with autologous tissue.

29.5 Patient Selection

The success of the reconstruction employing the transfer of the lower abdominal tissue will ultimately depend on two factors: patient selection and the selection of the right procedure.

The patient is assessed for risk factors. Increased complication rates after TRAM breast reconstructions are associated with the following risk factors: age (over 60 years), obesity (more than 25 % over ideal body weight), abdominal scars (primarily, Kocher, paramedian, or multiple abdominal surgical scars), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, previous radiotherapy applied to the chest wall, and smoking history.

I also consider it as indicated for patients who perform competitive high-impact sports or those who depend on intensive muscular dynamics at work (maids).

Anatomical assessment is also of paramount relevance, including abdominal contour and fat deposits (potbelly habitus patients are formally contraindicated for TRAM flaps).

The slender patient and those patients with poor abdominal strength or abdominal muscular laxity will not be considered for bipedicled TRAM flap reconstruction.

Preoperative testing by sit-ups is an easy and effective method to evaluate the abdominal strength. Patients who are not able to perform these movements are considered poor candidates too.

To select the right procedure, one simple question is mandatory: What are the patient’s needs?

The primary indication for the bipedicled TRAM flap is the need for a large amount of abdominal tissue to replace a large breast (Fig. 29.4). The second is a need for increased vascularity. Patients who have risk factors will benefit from the technique. When we take as an example fat necrosis, a typical complication with its origin in poor vascular supply, for monopedicled flaps, patients with two or more risk factors have three times the incidence of those with no or one risk factor. Patients with two or more risk factors who had bipedicled TRAM flaps had no associated increased incidence of fat necrosis. For flap loss complications, similar findings have been noted.

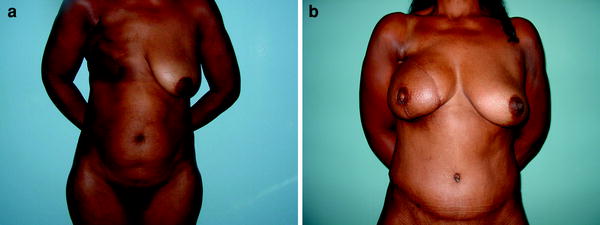

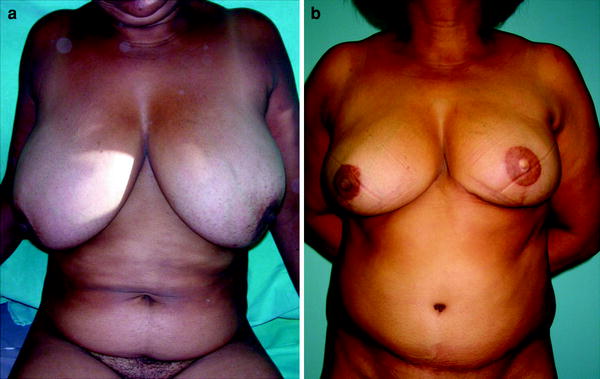

Fig. 29.4

Patients with large breasts benefit from double-pedicle harvesting. The whole abdominal flap can be safely raised

29.6 Patient Education and Preoperative Care

The patient is clearly informed about the procedure. Postoperative pain and 4–5 days of hospitalization is emphasized. The presence of drains that can remain for 1 week and the need for a synthetic mesh to reinforce the abdominal wall are also pointed out.

The recovery time is roughly 6 weeks, and the patient is made aware of a long resting period of not less than 2 months. The patient is also informed of weakness of the abdominal wall, mainly patients who undergo bilateral TRAM flap reconstructions.

Finally, potential complications are discussed and it is important that the patient is confident in the capacity of her surgeon to solve every problem related to an incidental failed reconstruction.

I rarely do immediate bilateral or free TRAM flap reconstructions. The extension of the operation added to the mastectomy procedure is not appealing. Perhaps on an institutional basis with a very well trained team it could be beneficial to the patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree