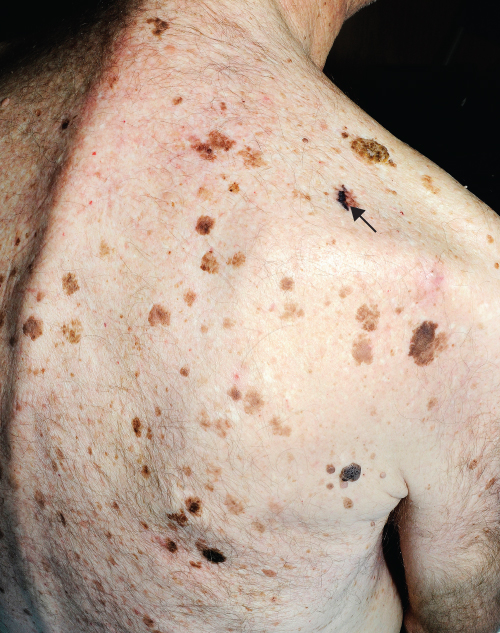

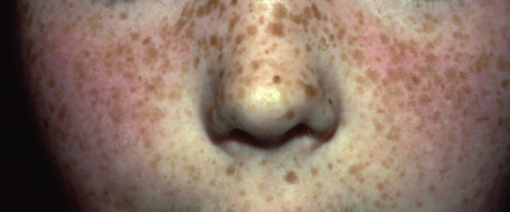

Chapter 21 Any cell within the skin can proliferate to form a benign lump or skin tumour. In general, a proliferation of cells can lead to hyperplasia (benign overgrowth) or dysplasia (malignancy/cancer). This chapter considers benign lesions, which by definition are harmless, but may cause symptoms such as pain, itching and bleeding or may be a cosmetic nuisance. Many benign skin lesions are pigmented, which can lead to a high level of anxiety for patients and occasionally medical staff as they may be confused with melanoma. Pattern recognition plays a valuable role in the correct diagnosis of benign skin lesions. The clinical features of any lesion can be a useful guide to distinguishing the benign from the malignant. However, if there is uncertainty as to the nature of any skin lesion after clinical examination then a diagnostic biopsy for histology is essential. The old adage ‘if in doubt cut it out’ may be appropriate if there is diagnostic uncertainty and skin experts are not available locally to see the patient. Benign cutaneous lesions are almost universally present on the skin of adults and are therefore so common that most are ignored and are never brought to medical attention. Nonetheless, the sudden appearance of new lesions, symptoms such as itching, pain or bleeding or the unsightly nature of lesions may bring them to the attention of the affected individual and thus the local practitioner. Reassurance is usually all that is needed. However, in some instances benign skin lesions need removal, for example, if they bleed persistently (pyogenic granulomas), they repeatedly catch on clothing (protuberant benign moles) or they cause pain (poroma on the foot). Some individuals are deeply affected by the cosmetic appearance of their benign skin lesions and these may therefore need removal on psychological grounds. From a medical practitioner’s point of view, we need to decide whether a lesion can be safely left or should be treated. This chapter concentrates on the correlation between clinical and pathological features of common benign tumours which should ease their diagnosis (Table 21.1). Chapter 22 examines premalignant and malignant skin tumours. Table 21.1 Differential diagnosis of common benign skin tumours. Seborrhoeic keratoses are increasingly common with increasing age. Lesions are most frequently seen on the trunk, face and neck in sizes varying from 0.5 to 3.0 cm in diameter. Seborrhoeic keratoses may be barely palpable, protuberant or pedunculated. They always have a warty dull surface. Colours are highly variable from pale tan through to dark brown (Figure 21.1). When deeply pigmented, inflamed or growing they can appear to have some malignant characteristics which may cause anxiety. Seborrhoeic keratoses, however, have some characteristic features which include Figure 21.1 Seborrhoeic keratoses on the trunk, there is a melanoma on the right upper shoulder (shown by the arrow). Figure 21.2 Seborrhoeic keratoses. These lesions are usually multiple small pigmented papules seen on the face of adults with black skin (Figure 21.3). Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN) is very common with up to one-third of individuals with skin type VI affected. Frequently, there is a strong familial tendency towards the condition. Typically the lesions occur on the cheeks, forehead, neck and chest. Histologically they resemble seborrhoeic keratoses; however, some experts think they arise from a developmental defect in the follicular unit. No treatment is needed, but if patients find the lesions cosmetically unacceptable then light electrodesiccation and gentle curettage can effectively remove lesions. New ones will inevitably form, however (see Chapter 23). Figure 21.3 Dermatosis papulosa nigra. Skin tags may be pigmented but are usually straightforward to diagnose. They are frequently multiple and more commonly occur at sites of occlusion where the skin may be rubbed by skin or clothing/jewellery in the axillae, neck, groin and under the breasts (Figure 21.4). If they are catching on clothing and so on, they can be removed by ‘snip/shave’ under local anaesthetic. Figure 21.4 Skin tags. Patients often refer to solar-induced freckles as ‘sun spots’ or ‘liver spots’. Lentigines are small macular well-demarcated pigmented lesions that usually occur on sun-exposed skin (Figure 21.5). They first appear in childhood and generally increase in number with increasing age. Lentigines are more common in individuals with fair rather than dark skin types. The colour of the lentigines varies from pale tan to almost black, which usually corresponds to the amount of melanin pigment produced by the increased number of melanocytes. In contrast to moles where the melanocytes form nests (naevi), the melanocytes in lentigines line up along the basement membrane. Figure 21.5 Lentigines. Benign lentigines may also occur on the lip and genital mucosa. Labial lentigines may be associated with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (an inherited condition with gastrointestinal polyps), Laugier–Hunziker syndrome (which has associated nail pigmentation) and LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxomas and blue naevi). In LEOPARD syndrome (lentigines, electrocardioconduction defects, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormal genitalia, retardation of growth and deafness) lentigines are characteristically seen on the neck and trunk. No treatment is usually required for lentigines; however, treatment with liquid nitrogen may help them fade. The majority of moles are benign and can be safely ignored. However, knowing which are potentially harmful or malignant can be difficult for inexperienced practitioners. Clinical features of benign moles will be considered in this chapter to aid their diagnosis. Malignant moles are considered in Chapter 22. The term naevi is derived from the Greek word meaning ‘nest’. A proliferation of melanocytes forms these nests at different levels in the skin resulting in moles. If the nests of melanocytes are confined to the dermoepidermal junction, then the mole is referred to as junctional naevus, if they are in the dermis only, ‘intradermal naevus’ and if present in the epidermis and dermis, ‘compound naevus’. Naevi may be congenital (‘birth mark’) or acquired, usually in early childhood. The number of moles usually remains static in adulthood with a decline after the sixth decade.

Benign Skin Tumours

OVERVIEW

Introduction

Clinical features

Differential diagnoses

Pigmented

Seborrhoeic keratoses, dermatosis papulosa nigra, freckles (lentigines), solar lentigo, melanocytic naevus, blue naevus, Mongolian blue spot, dermatofibroma, apocrine hidrocystomas

Vascular

Naevus flammeus, strawberry naevus, port-wine stain, spider naevi, Campbell de Morgan spots, pyogenic granuloma

Papules

Skin tags (fibroepithelial polyps), milia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, dermatosis papulosa nigra, syringomas, trichoepitheliomas, apocrine hidrocystomas

Nodules

Dermatofibroma, lipoma, angiolipoma, epidermoid cyst, pilar cyst, pilomatrixoma, poroma, intradermal naevus, apocrine hidrocystomas

Plaques

Naevus sebaceus, epidermal naevus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus (ILVEN), seborrhoeic keratoses

Pigmented benign tumours

Seborrhoeic keratoses

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN)

Skin tags

Lentigines (freckles)

Melanocytic naevi

Congenital melanocytic naevi

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree