Beauty: An Historical and Societal Perspective

Pearl E. Grimes

Historical Perspective

Beautiful faces are those that wear

It matters little if dark or fair

Whole-should honesty printed there.

–“Beautiful Things” ELLEN ATHERTON

Historical definitions of beauty

If you ask patients to define “beautiful people,” they will probably cite modern-day icons or historical legends renowned for their beauty. Such examples include Cleo-patra, Angelina Jolie, or Halle Berry. But what do their answers tell us? White or black, Asian or Hispanic, beautiful people brought to mind probably share key attributes. For instance, virtually every culture has celebrated smooth skin, albeit a surface that is sometimes painted, tattooed, or pierced for extra appeal. Symmetry of features has long been a lure, if only subconsciously. Proportion, which represents the ratio of facial features relative to attraction, has held surprisingly steady over the centuries. Is there a recognized definition of beauty and, if so, where does it originate?

The accepted definition of beauty is based on ancient methods of quantifying beauty and applying those principles to all forms of nature. The ancient Egyptians may have been among the first to describe facial characteristics relative to beauty during the fourth and fifth centuries, but the ancient Greeks were the ones who appear to have quantified it. The artist Polykleitos, in the fifth century B.C., laid down recommended ratios for the ideal proportions in figures.1 Those recommendations were later modified and refined. The Romans adapted the Greek canon, which developed and became known as the Golden Proportion. This ideal highlighted the connection between harmony, order, and proportion. This theme of defining beauty continued through the Middle Ages and was adapted during the Renaissance. In 1741, Pére André described beauty as the balance of “Unity, order, proportion and symmetry.”2 No doubt many people would say the same today, even if they can’t articulate their attraction to certain objects.

Studies have shown that few people fit the historical canons of beauty.3 In the 19th century, a group of anthropologists in Frankfort agreed on standard cranial measurements that have since been used to measure attractiveness in addition to the earlier canons. History has shown that certain ideals are found attractive in most societies. Certain characteristics and proportions can be seen as universal. However, different methodologies, genetic algorithms, and modern digital facial manipulations that identify and define beauty have shown that there is no clear answer to the question “What is beauty?”4,5

Beautiful women in society: historical icons

Beautiful women have been etched onto cave walls, carved in stone, painted on canvas, and paid homage to in song, poetry, and prose. They have been with us since the beginning of time. The Greeks had the mythology of Aphrodite; the Norse had Freya. Hindu mythology reveres Lakshmi as the goddess of beauty. The Romans called their mythological goddess Venus.

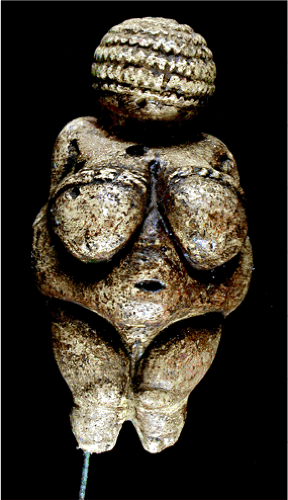

The Venus of Willendorf is one of the oldest depictions of a human woman, an icon of prehistoric art, created nearly 30,000 years ago (Fig. 1-1). She was almost certainly a celebration of procreation and nurturing. By today’s Western standards, however, she would be unlikely to find herself on the cover of Vogue, Elle, or Essence magazines.

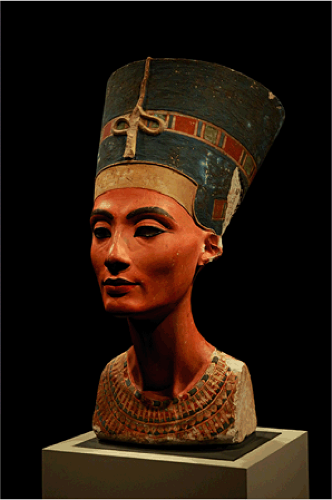

Throughout history, there are examples of mutual appreciation of beauty across ethnic divides. Nefertiti and the Queen of Sheba are renowned beauties believed to have been black Africans (Fig. 1-2). The Queen of Sheba was from present-day Ethiopia or Yemen and is well known in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic texts. In Greek mythology, there were the celebrated black figures Isis from the Nile Valley and Diana of Attica from Ethiopia.

Pocahontas, the daughter of Chief Powhatan, was reportedly a beautiful and intelligent woman who was treated as royalty. The most well-known, idealized painting of her, The Baptism of Pocahontas,5 depicts her as a lighter-skinned, virginal beauty compared with the other Indians in the picture.

As stated by Margaret Hungerford in 1878, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and David Hume in 1757, “Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” But is this true? Is everyone’s idea of beauty distinctly individual, or is there a template laid down in our genes against which we measure it? How much does the ideal vary from race to race or from culture to culture? Can exposure to new ideals influence our perception of beauty?

In our multiracial, multicultural, and multimedia society, it is difficult to tease out the factors that define beauty. Instead, observation of historical or isolated populations provides clues about the perception of beauty and the way it changes over time.

Genetic and Evolutionary Aspects of Beauty

From an evolutionary perspective, beauty is a gauge to measure fitness and suitability of a mate. Attractive facial features may signal sexual maturity and fertility, emotional expressiveness, or confer a cuteness that evokes a protective instinct.6 As a “survival-of-the-fittest” instinct, avoidance of deformity and disease directs us toward mates who exude health and vitality. Symmetrical features, healthy bodies, and flawless skin are idealized. These parameters are commonly used to define physical beauty—but they also leave room for variability and interpretation.

There is clear agreement that attractiveness ratings are similar in a number of cross-cultural studies.7,8 When considering the genetic angle of defined beauty, men are attracted to delicate jaws, large eyes, narrow waists, and full hips and lips, probably because these features signal youth and a high estrogen level, which in turn means fertility and fecundity. Women, on the other hand, are attracted to strong chins, height, broad shoulders and wide jaws, probably because they signal a high testosterone level and imply an ability to protect and feed a family.9,10

The pursuit of beauty is a basic instinct and a biological adaptation to help ensure the survival of our genes and, in a sense, ourselves. Research suggests that sensitivity to beauty is due to an instinct that has been shaped by natural selection.11 For example, certain studies show that infants will stare significantly longer at faces deemed by adults to be attractive.12 In addition, mothers of attractive newborns spend more time interacting with their babies. Studies have also shown a disproportionate number of abused children may not fit the standard canons for beauty.12

In other words, beautiful people are excused for everything from stupidity to serious crimes. People are more likely to help the good-looking (even if they dislike them) and are less likely to ask them for help.13,14,15 A common theory even has it that beauty is the appearance of things and people that are good, meaning attractive people are judged more worthy simply because of their looks.

Beauty clearly brings ease. It is, as they say, its own reward.14

Beauty clearly brings ease. It is, as they say, its own reward.14

Measurements for Facial Aesthetics

Anatomical beauty is relatively easy to define and measure. Population surveys have identified the facial features that contribute to a generalized ideal. These include a full head of hair, smooth complexion, large eyes, small nose, full lips, slightly protrusive lower face, and high cheekbones. On the other hand, facial features that detract from beauty are disproportion, asymmetry, excessive size, convexity of profile, retrusion of the chin, skin laxity, thin lips, large nose, and irregular or discolored teeth.16

Historical tools or parameters used to measure facial aesthetics include the golden aesthetic proportions, neoclassical canons of facial proportion, the Frankfort horizontal plane, and facial shapes (Table 1-1).

The Greeks were fascinated by beauty as conveyed by the pursuit of godlike perfection in their statues. They also considered mathematics to be the unifying basis of life, art, the gods, and the universe. It is therefore no surprise that they tried to define beauty with mathematics. The divine proportion, or “golden section,” was taken up by Plato as a mathematical relationship expressing universal harmony. Considered an ideal measure to govern the relationship of elements of the human body, it is expressed as 1:1.618, a ratio that occurs in many natural forms such as plants, shells, and snowflakes. Leonardo da Vinci later used the “golden section” in his portraits. The apparent importance of the ratio led Ricketts, an orthodontist, in 1982 to postulate a divine proportion for facial analysis.17 This concept is believed to have originated with the sculptor Phidias, hence the expression phi in relation to the golden proportion, which has been used as an aesthetically pleasing relationship of vertical and/or horizontal structures. Ricketts indicated that this relationship seems to occur naturally in a variety of guises in the human face and body. However, in 1992, Davis and Jahnke disputed the relevance of the “golden section.” They demonstrated a preference for internal facial divisions with a unitary value with bilateral symmetry.18

Table 1-1 Aesthetic parameters of the face | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

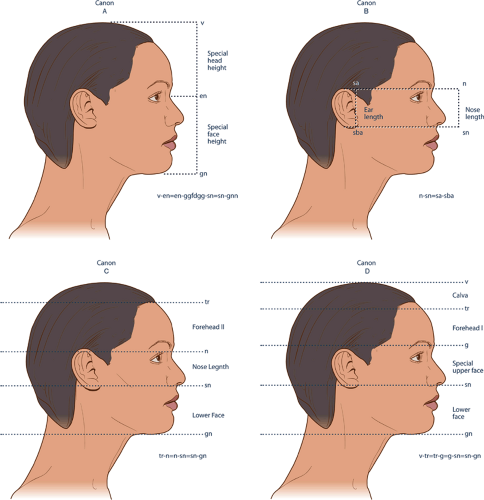

The neoclassical canons of facial proportions, described by scholars and artists of the Renaissance based on classical Greek canons, are still used for evaluation of facial features today (Table 1-1). Standard canons include the division of the face profile into thirds, with the height from the hairline to the eyebrow, from the brow to the lower edge of the nostril, and from the nostril to the chin being equal (Fig. 1-3). Other guidelines state that the height of the nose and the ear be the same, the width of the mouth be one and a half times the width of the nose, and the inclination of the nose bridge be parallel to the axis of the ear.

In 1985, Farkas et al. suggested that the facial canons did not work well when used to measure beauty in contemporary white subjects.19 How would the canons perform

across ethnic boundaries? Matory assessed the applicability of various parameters of attractiveness in 400 “attractive” subjects representing different ethnic and racial groups: black Americans, Hispanic, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Caucasian.20 The neoclassical canons were inconsistent in each of the ethnic categories. The face could be divided into three equal parts, and the face and cranium into four equal parts, in fewer than 9% and 4% of individuals, respectively.

across ethnic boundaries? Matory assessed the applicability of various parameters of attractiveness in 400 “attractive” subjects representing different ethnic and racial groups: black Americans, Hispanic, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Caucasian.20 The neoclassical canons were inconsistent in each of the ethnic categories. The face could be divided into three equal parts, and the face and cranium into four equal parts, in fewer than 9% and 4% of individuals, respectively.

Figure 1-3 Golden Proportion and Neoclassical Canons. A: Two-section facial profile canon. The combined head-face height is divided into two equal parts: the special head height (vertex-endocanthion, v-en) and the special face height (endocanthion-menton, en-gn). B: Nasoaural proportion canon. The length of the nose (nasion-subnasale, n-sn) equals the length of the ear (supraaurale-subaurale, sa-sba). C: Three-section facial profile canon. The combined forehead-face height is divided into three equal parts: the forehead (trichion-nasion, tr-n), the nose (nasion-subnasale, n-sn), and the lower half of the face (subnasle-gnathion, sn-gn). D: Four-section facial profile canon. The combined head-face height is divided into four equal parts: the height of the calva (vertex-trichion, v-tr), the height of the forehead (trichion-glabella, tr-g), the special upper face height (glabella-subnasale, g-sn), and the height of the lower face (subnasale-gnathion, sn-gn). (Modified from

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Farkas LG, Hrecko TA, Kolar JC, et al. Vertical and horizontal proportions of the face in young adult North American Caucasians: revision of neoclassical canons. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985;75(3):328–337

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|