61

Bacterial Diseases

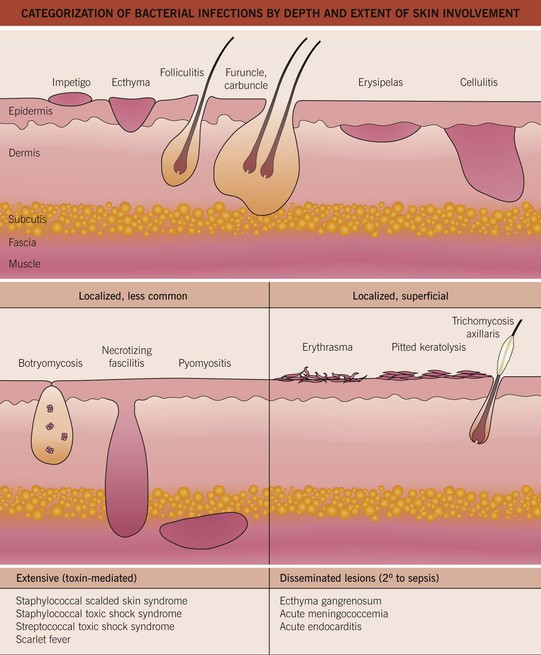

Skin infection with bacteria may be a primary problem (e.g. impetigo) or a complication of another skin disease (e.g. atopic dermatitis). Nomenclature of these diseases often reflects the site and the depth of infection – that is, from the stratum corneum to the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 61.1) – as well as the suspected causative organism.

Fig. 61.1 Categorization of bacterial infections by depth and extent of skin involvement. More common, localized infections are depicted first; these infections are often secondary to Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococci. Adapted from ‘Common bacterial infections of the skin,’ American Academy of Dermatology.

Gram-Positive Cocci

Staphylococcal and Streptococcal Skin Infections

Streptococcal infections may be complicated by acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis; this occurs in <1% of patients in high-income countries, but it remains a significant problem in low-income countries.

Impetigo

• Major organisms are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci [GAS]).

• A very common, highly contagious bacterial infection, most commonly seen on the face or extremities of children; usually the skin is eroded with overlying ‘honey-colored’ crusts, but there is a bullous variant (Fig. 61.2).

Fig. 61.2 Staphylococcal impetigo. A Honey-colored crusts on the chin and cheeks of a child with impetigo. B Superficial bullae and dry erosion on the nose due to bullous impetigo. A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Interestingly, bullae formation due to S. aureus can be explained by local release of an exfoliative toxin that binds to desmoglein 1 and leads to dissolution (i.e. acantholysis) of the upper epidermis (see Chapter 23).

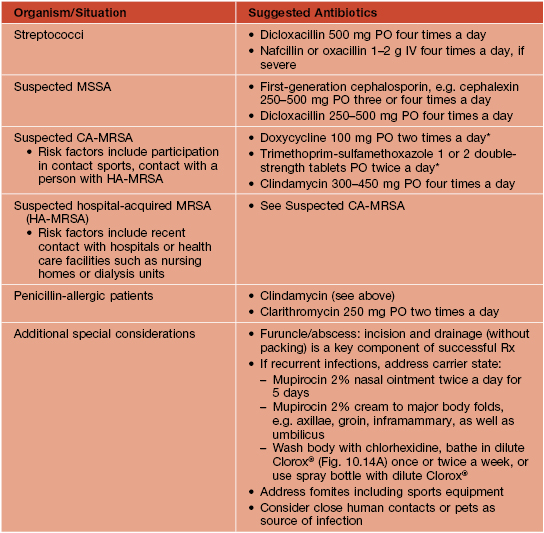

• Rx: local wound care (including soap), removal of crusts by soaking; for mild cases, topical mupirocin or retapamulin; for moderate to severe infections, oral antibiotics, the choice of which is dependent on prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the local community (Table 61.1).

Table 61.1

Empiric treatment of cutaneous staphylococcal and streptococcal infections in adults.

Treatment duration is usually 7–10 days, depending on the severity and clinical response. Initial choice of antibiotic is dependent on known resistance patterns in a given community. The contents of pustules or exudate (e.g. underlying a crust) should be sent for culture and sensitivities prior to beginning therapy. Quinolones and macrolides are not optimal for treatment of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) because resistance is common and may develop rapidly.

* Does not provide coverage of group A streptococci; if coverage of the latter is desired, a β-lactam is also prescribed.

MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Ecthyma

• Most commonly secondary to Streptococcus pyogenes.

• Ulceration with hemorrhagic crust that extends into the superficial dermis, i.e. is deeper than impetigo (Fig. 61.3); can heal with scarring.

Fig. 61.3 Ecthyma. Ulceration with hemorrhagic crust on the wrist due to infection with group A streptococci. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Bacterial Folliculitis

• Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause, followed by gram-negative bacteria; the latter can occur in patients with acne vulgaris on long-term antibiotic therapy; see Chapter 31 for Pseudomonas folliculitis.

• Usually superficial, but occasionally deep, infection centered on hair follicles (see Fig. 61.1).

– Superficial – 1- to 4-mm pustules on an erythematous base (see Fig. 31.2); centrally, a hair shaft may be noted.

• DDx: culture-negative (normal flora) folliculitis, acne vulgaris, folliculitis due to fungi (e.g. Pityrosporum) or viruses (e.g. herpes simplex virus), rosacea, and pseudofolliculitis barbae (see Chapter 31).

• Rx: for superficial form – antibacterial washes (e.g. benzoyl peroxide, chlorhexidine) or topical gels (e.g. combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide); widespread staphylococcal folliculitis – oral antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

Abscesses, Furuncles, and Carbuncles

• By definition, a furuncle involves a hair follicle; involvement of multiple, adjacent follicles is termed a carbuncle (see Fig. 61.1).

• Clinically, furuncles appear as firm, tender, red nodules; carbuncles begin similarly but become larger in size and can develop multiple draining sinus tracts.

• Common locations are the face, neck, axillae, buttocks, perineum, and thighs.

• DDx: ruptured epidermoid inclusion cyst, hidradenitis suppurativa, and cystic acne.

• Rx: fluctuant lesions should be incised and drained; systemic antibiotics are generally reserved for: (1) furuncles around the nose, in the external auditory canal, or in other locations where drainage is difficult; (2) severe or extensive disease (e.g. multiple sites); (3) lesions with surrounding cellulitis/phlebitis or associated with signs or symptoms of systemic illness; (4) lesions not responding to local care; and (5) patients with concerning comorbidities or immunosuppression (see Table 61.1 for Rx options).

Erysipelas

• Most commonly due to Streptococcus pyogenes.

• Presents as a well-defined area of hot, indurated, bright erythema that is painful and tender (Fig. 61.4); occasionally, there may be superimposed pustules, vesicles, bullae, or areas of hemorrhagic necrosis.

Fig. 61.4 Cutaneous manifestations of streptococcal infections. Prominent desquamation of the feet (A) following scarlet fever. Sharply demarcated erythema of the face, most obvious on the forehead (B), and of the buttocks (C) in two patients with erysipelas. Bright red erythema extending from the anal verge in a young boy with streptococcal perianal disease (D). A, Courtesy, Eugene Mirrer, MD; B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; C, Courtesy, Mary Stone, MD; D, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Favors the young, debilitated, elderly, and limbs with edema or lymphedema.

Cellulitis

• Infection of the deep dermis and sometimes the subcutaneous fat (see Fig. 61.1).

• Skin rubor (redness), calor (warmth), dolor (pain), and tumor (swelling) are present; more ill-defined borders than erysipelas and may have skip areas; can become bullous or necrotic (Figs. 61.5 and 75.8).

Fig. 61.5 Bullous cellulitis. Extensive soft tissue infection of the lower extremity due to group A streptococcal infection.

• Systemic symptoms include fever, chills, and malaise; CBC usually shows leukocytosis and bandemia.

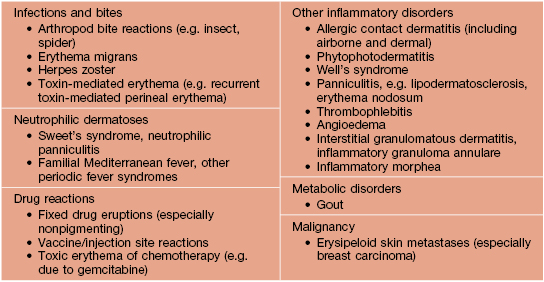

• DDx: on the lower extremity, lipodermatosclerosis and stasis dermatitis (see Fig. 11.5); elsewhere, erysipelas and the early stage of necrotizing fasciitis, as well as causes of pseudocellulitis (Table 61.2).

Blistering Distal Dactylitis

Botryomycosis

• Most commonly caused by S. aureus, followed by Pseudomonas spp.

• Grains, representing macroscopic colonies of bacteria, are seen in biopsy specimens as well as the pustular discharge; grains are also seen in eumycotic and actinomycotic mycetoma (see Chapter 64) and actinomycosis (see below).

• Often develops at sites of trauma.