Introduction548

INTRODUCTION

SUPERFICIAL PYOGENIC INFECTIONS

IMPETIGO

Common impetigo

Bullous impetigo

Histopathology

Fig. 23.1

STAPHYLOCOCCAL ‘SCALDED SKIN’ SYNDROME (SSSS)

Staphylococcal epidermolytic toxin syndrome

Histopathology54

Fig. 23.2

STAPHYLOCOCCAL TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME

Histopathology61

STREPTOCOCCAL TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME

Histopathology

PERIANAL STREPTOCOCCAL DERMATITIS

ECTHYMA

Histopathology

DEEP PYOGENIC INFECTIONS (CELLULITIS)

ERYSIPELAS

Histopathology

Fig. 23.3

ERYSIPELOID

Histopathology168

BLISTERING DISTAL DACTYLITIS

CELLULITIS

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

Histopathology207. and 208.

MISCELLANEOUS SYNDROMES

Clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene)

Progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene

Erosive pustular dermatosis

Histopathology

BLASTOMYCOSIS-LIKE PYODERMA

Histopathology

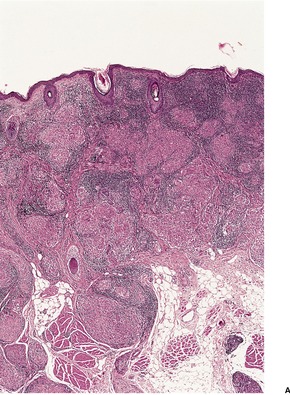

Fig. 23.4

CORYNEBACTERIAL INFECTIONS

DIPHTHERIA

Histopathology

ERYTHRASMA

Histopathology

Fig. 23.5

Electron microscopy

TRICHOMYCOSIS

PITTED KERATOLYSIS

Histopathology306. and 314.

Fig. 23.6

NEISSERIAL INFECTIONS

MENINGOCOCCAL INFECTIONS

Histopathology

GONOCOCCAL INFECTIONS

Histopathology

MYCOBACTERIAL INFECTIONS

TUBERCULOSIS

Classification

Primary tuberculosis

Histopathology393

Lupus vulgaris

Histopathology425

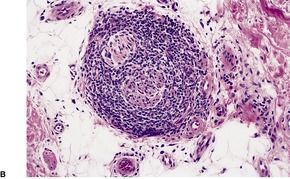

Fig. 23.7

Tuberculosis verrucosa

Scrofuloderma

Histopathology332

Orificial tuberculosis

Histopathology

Disseminated cutaneous tuberculosis

Histopathology502

Tuberculids

Histopathology

Treatment of cutaneous tuberculosis

INFECTIONS BY NON-TUBERCULOUS (ATYPICAL) MYCOBACTERIA

Mycobacterium ulcerans infection (Buruli ulcer)

Histopathology568. and 580.

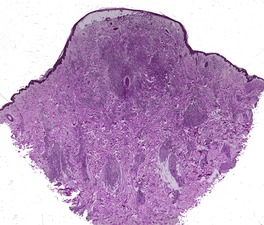

Fig. 23.8

Mycobacterium marinum infection (swimming pool granuloma)

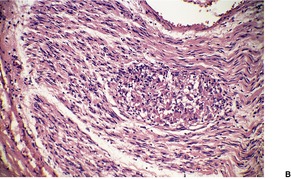

Histopathology605.606. and 607.

Fig. 23.9

Other non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria

Treatment of non-tuberculous mycobacteria

Histopathology330

LEPROSY

Clinical classification of leprosy

Reactional states in leprosy735

Treatment of leprosy

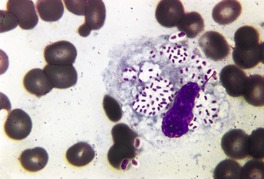

Histopathology735. and 753.

Fig. 23.10

Fig. 23.11

Fig. 23.12

Fig. 23.13

Fig. 23.14

Fig. 23.15

MISCELLANEOUS BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

ANTHRAX

Histopathology844.845. and 857.

BRUCELLOSIS

Histopathology858. and 859.

YERSINIOSIS

Histopathology

GRANULOMA INGUINALE

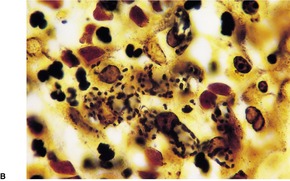

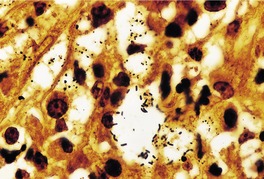

Histopathology868. and 874.

Fig. 23.16

Fig. 23.17

Electron microscopy

CHANCROID

Histopathology878. and 890.

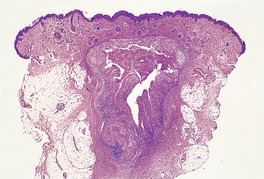

RHINOSCLEROMA

Histopathology

Fig. 23.18

Fig. 23.19

Electron microscopy

TULAREMIA

Histopathology

LISTERIOSIS

Histopathology

CAT-SCRATCH DISEASE

Histopathology916. and 932.

Fig. 23.20

MALAKOPLAKIA

Histopathology935

‘SAGO PALM’ DISEASE

Histopathology

CHLAMYDIAL INFECTIONS

PSITTACOSIS

LYMPHOGRANULOMA VENEREUM

Histopathology

RICKETTSIAL INFECTIONS

Disease

Organism

Mode of transmission

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

R. rickettsii

Tick

Boutonneuse fever

R. conorii

Tick

African tick bite fever

R. africae

Tick

Rickettsialpox

R. akari

Mite

Siberian tick typhus

R. sibirica

Tick

Queensland tick typhus

R. australis

Tick

Epidemic typhus

R. prowazakii

Louse feces

Murine typhus

R. mooseri (typhi)

Flea feces

Scrub typhus

O. tsutsugamushi

Mite

Q fever

Coxiella burnetii

Aerosol

Histopathology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Bacterial and rickettsial infections

Superficial pyogenic infections548

Deep pyogenic infections (cellulitis)551

Rickettsial infections572

Various bacteria form part of the normal resident flora of the skin. In the past, these organisms were regarded as symbiotic, but there is emerging evidence that these organisms may protect the host; as such they are mutualistic rather than symbiotic. 1 This subject has been reviewed recently (2008). 1 In certain circumstances some of these bacteria may assume pathogenic importance. Other bacteria are present only in pathological circumstances. In this chapter the following categories of bacterial infections will be considered: pyogenic, corynebacterial, neisserial, mycobacterial, miscellaneous, chlamydial, and rickettsial. Pyogenic infections, usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus and strains of Streptococcus, are numerically the most important bacterial infections of the skin. Staph. aureus-mediated skin infections require the adherence of the organism to the epidermis, if the skin surface is intact. Following adherence, the organism then invades keratinocytes, resulting in cytokine production and release. 2 It has recently been found to induce the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in keratinocytes. 3 Even exfoliative toxin-negative strains of Staph. aureus possess exotoxins capable of disrupting the barrier function of tight junction proteins. 4 Two distinct groups of pyogenic infection (superficial and deep) can be distinguished on the basis of the anatomical level of involvement of the skin. The pyogenic infections, with the exception of the staphylococcal ‘scalded skin’ syndrome, which results from the effects of a bacterial exotoxin, are characterized histologically by a heavy infiltrate of neutrophils. These organisms may also infect hair follicles, resulting in folliculitis. Furuncles (see p. 404) are deep-seated acute infections based on the pilosebaceous unit and adjacent dermis. They are of interest because of their association with Staph. aureus expressing the Panton–Valentine leukocidin genes. 5 This strain is found in 42% of isolates from furuncles, and in all cases of epidemic furunculosis. 5

Corynebacterial infections, with the exception of diphtheria, are usually limited to the stratum corneum and, as a consequence, there is no significant inflammatory response: at first glance, the biopsy may appear normal.

Neisserial infections of the skin are rare, although they are an important cause of urethritis. Cutaneous lesions may occur in neisserial septicemias.

Mycobacterial infections usually result in a granulomatous tissue reaction, but this depends on the immune status of the individual, including the development of delayed hypersensitivity. Exceptions include lepromatous leprosy, in which a histiocytic response occurs, and some infections by atypical mycobacteria, in which suppurative granulomas, suppuration, and even non-specific chronic inflammation may result at various times.

A variety of inflammatory reactions can be seen in the group of miscellaneous bacterial infections of the skin. The chapter closes with a brief discussion of chlamydial infections and rickettsial infections. Each group will be discussed in turn.

Although they are bacteria, infections by the actinomycetes are considered in Chapter 25 (pp. 600–602) because they produce lesions that are clinicopathologically similar in many respects to those produced by some fungi (mycetomas).

Although there are many facets to the defense mechanisms that the body has to various microorganisms, there has been recent interest in toll-like receptors (TLRs) as essential components of the innate immune system. 6 Each TLR so far recognized binds with specific ligands. For example, TLR-2 predominantly recognizes Gram-positive bacterial components. 6

For some of the diseases that follow, treatment options will be considered only briefly, or not at all. This is because antibiotic sensitivity of some organisms varies widely from country to country, and cost becomes an additional limiting factor to antibiotic choice in some communities. Vaccines are currently available for several bacterial diseases including anthrax, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis. 7

The superficial pyogenic infections of the skin (pyodermas) include impetigo and its variants and ecthyma. They also include the superficial infections of the hair follicles, which are dealt with in Chapter 15 (pp. 402–404). In addition, the staphylococcal ‘scalded skin’ syndrome can be included in this category, although the lesions result from the action of bacterial toxin rather than local infection itself.

Impetigo is an acute superficial pyoderma which heals without scar formation. It is the most common bacterial infection of the skin in childhood.8.9.10. and 11. Its incidence appears to be increasing. 12 Adults are sometimes affected, particularly athletes, military personnel, and those in institutions. 13 Minor trauma, especially from insect bites, as well as poor hygiene and a warm, humid climate, all predispose to this infection.14. and 15. Seasonal variation in its occurrence has been noted.16. and 17.

There are two clinical forms of impetigo: a common, vesiculopustular type, and a bullous variant, which is considerably less frequent.18. and 19. Recent studies have shown that Staphylococcus aureus is now the most common organism isolated from the non-bullous type of impetigo,20.21. and 22. which in the past was caused mostly by a group A β-hemolytic streptococcus, sometimes with Staph. aureus as a secondary invader.10. and 13. Anaerobes are now isolated in a number of cases. 22 The bullous form has always been related exclusively to Staph. aureus, usually of phage group II. 23 Both bullous and non-bullous forms of impetigo are associated with exfoliative toxins. Exfoliative toxin genes were present in one study in 100% of Staph. aureus isolates from bullous impetigo and from 57% of isolates from non-bullous impetigo. 5

The incidence of strains of Staph. aureus resistant to the antimicrobial agents used in the treatment of impetigo has been increasing; MRSA accounts for less than 20% of such infections. 24 An ointment containing an equal blend of gentamicin and fusidic acid has been widely used in Japan and some European countries to treat localized impetigo. 24 Sensitivity to fusidic acid has decreased significantly in recent years. 17 Bacitracin is commonly used, but its efficacy is questionable. 25 Topical mupirocin can be an effective treatment option, as are older treatments such as topical gentian violet and vioform. 25 Other topical treatments with some benefit include topical hydrogen peroxide cream, and tea lotion and cream. 25 Topical retapamulin, which belongs to a new class of antibiotics, is an effective and safe treatment for impetigo. 26 Clindamycin has shown excellent activity against most isolates of Staph. aureus and can be used for more serious disease. Other antimicrobials that can be used include dicloxicillin, cloxacillin, cephalexin, or amoxicillin combined with potassium clavulanate. 25

Common impetigo (‘school sores’) commences as thin-walled vesicles or pustules on an erythematous base: the lesions rapidly rupture to form a thick, golden crust. 27 Common impetigo occurs as a solitary lesion or a cluster of several lesions, which may coalesce. It is found on the face or extremities. 21 Local lymphadenopathy may be present.

Some authors use the term impetigo contagiosa (non-bullous impetigo) for this group, and restrict the term common impetigo to a secondary impetigo that may complicate systemic disease, or dermatological conditions that cause a break in the skin. 25

Bullous impetigo is composed of shallow erosions and flaccid bullae, 0.5–3 cm in diameter, with an erythematous rim. 13 The bulla has a thin roof which soon ruptures, resulting in a thin crust. 23 There may be a localized collection of a few bullae, or more generalized lesions.28. and 29. Bullous impetigo is included with the staphylococcal epidermolytic toxin syndrome, as the lesions result from the production in situ of an epidermolytic toxin by staphylococci. 13

Common impetigo is rarely biopsied, as the diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds. An early lesion will show a subcorneal collection of neutrophils, with exocytosis of these cells through the underlying epidermis. A few acantholytic cells are sometimes seen, but this is never a prominent feature. Established lesions show a thick surface crust composed of serum, neutrophils in various stages of breakdown, and some parakeratotic material. Gram-positive cocci can usually be found without difficulty in the surface crust.

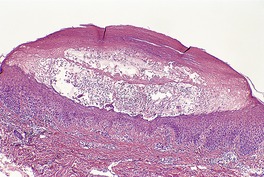

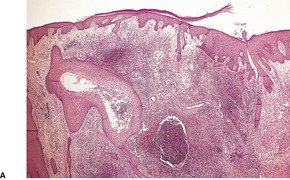

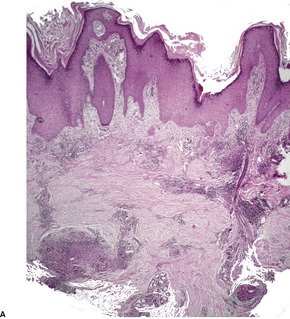

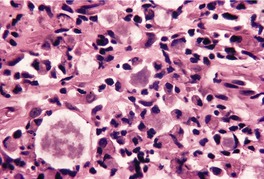

In bullous impetigo the subcorneal bulla contains a few acantholytic cells, a small number of neutrophils, and some Gram-positive cocci (Fig. 23.1). 23 In contrast to the lesions of the staphylococcal ‘scalded skin’ syndrome, there is usually a mild to moderate mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the underlying papillary dermis. 23

Bullous impetigo. There is a subcorneal blister containing inflammatory cells and degenerate keratinocytes. Gram-positive cocci were found. (H & E)

The staphylococcal ‘scalded skin’ syndrome results from the production of an epidermolytic toxin by certain strains of Staph. aureus, most notably type 71 of phage group II.13. and 30. Our understanding of these bacterial strains is now much more sophisticated. Exfoliative toxins result from the presence of certain genes (eta, etb, and etd) in the organism. These genes encode for ETA, ETB, and ETD respectively. 5 These organisms are responsible for a preceding upper respiratory tract infection, conjunctivitis, or carrier state. Rarely, the syndrome follows a staphylococcal infection complicating varicella or measles.31. and 32.

The SSSS predominantly affects healthy infants and children younger than 6 years, apparently reflecting an inability to handle and excrete the toxin. 33 Rarely, neonates are involved, a condition known in the past as Ritter’s disease (Ritter von Rittershain’s disease). 34 A few cases have been reported in adults, in whom there has usually been underlying immunosuppression (including the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome)35. and 36. and/or renal insufficiency.37.38. and 39. It occurs rarely in healthy adults.40.41.42.43. and 44.

There is a sudden onset of skin tenderness and a scarlatiniform eruption which is followed by the development of large, easily ruptured, flaccid bullae and a positive Nikolsky sign. 34 Desquamation of large areas of the skin occurs in sheets and ribbons. 37 Occasionally, only the scarlatiniform eruption develops. The usual sites of involvement are the face, neck, and trunk, including the axillae and groins. Mucous membranes are not involved.

The disease has a good prognosis in children, with spontaneous healing after several days as a consequence of the formation of neutralizing antibodies to the epidermolytic toxin. 45 In adults a staphylococcal septicemia may ensue and is sometimes fatal. Concurrent SSSS and toxic shock syndrome are extremely rare. 46 A chronic case, evolving over 2 years, has been reported in an adult female patient. 47

Desquamation results from the effects of an exotoxin of low molecular weight (exfoliatin), produced by certain strains of Staph. aureus. There are two forms of exfoliatin recognized – exfoliative toxin A (ETA), which is chromosomally encoded, and exfoliative toxin B (ETB), which is plasmid encoded. 48 Other exfoliative toxins have been described (ETD). 5 Exfoliative toxins act as serine proteases which cleave desmoglein 1 in the superficial epidermis. 49 The condition can be reproduced in newborn mice by the subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection of these organisms. 50

The treatment of SSSS involves parenteral antibiotics, such as dicloxacillin, to eradicate the Staph. aureus, and appropriate nursing care to prevent the secondary effects of disrupted skin barrier function. 36

The SSSS, which was historically considered (incorrectly) to be a variant of toxic epidermal necrolysis (see p. 53), has been regarded as belonging to the staphylococcal epidermolytic toxin syndrome.51.52. and 53. Also included in this concept are localized and generalized bullous impetigo, which result from the local production (as opposed to production at a distant site, as in SSSS) of a similar staphylococcal epidermolytic toxin. 31 Consequently, in bullous impetigo the organisms may be demonstrated within the lesion. Impetigo is discussed in further detail above.

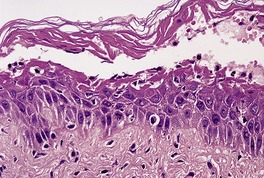

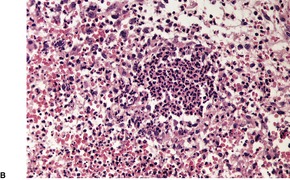

In the SSSS there is subcorneal splitting of the epidermis (Fig. 23.2). A few acantholytic cells and sparse neutrophils may be present within the blister, although often it is difficult to obtain an intact lesion. A sparse, mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate is present in the underlying dermis. This is in contrast to generalized bullous impetigo, and even pemphigus foliaceus, in which the dermal infiltrate is heavier.

The staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome with subcorneal splitting. (H & E)

Immunofluorescence is negative, in contrast to pemphigus foliaceus, in which intercellular immunoreactants are usually demonstrable.

The staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome was first recognized over a decade ago in healthy menstruating women who used tampons.55. and 56. It results from a toxin produced by certain strains of Staph. aureus that proliferate in the vagina and cervix. The organisms possess the gene tst (toxic shock syndrome toxin gene). 5 The syndrome may also result from the production of one of the staphylococcal enterotoxins. 57 These toxins appear to activate T lymphocytes with the production of various cytokines. 58 The toxic shock syndrome can also complicate wound infections with Staph. aureus. 59 Currently, the incidence of non-menstrual disease exceeds that related to the female genital tract.30. and 60. The clinical features of this syndrome include a fever, hypotension, inflammation of mucous membranes, vomiting and diarrhea, and cutaneous lesions that resemble viral exanthemas or erythema multiforme.61. and 62. The skin lesions undergo desquamation in time.

A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome has also been reported (see below).

The characteristic features of the toxic shock syndrome are small foci of epidermal spongiosis containing a few neutrophils, scattered degenerate keratinocytes, sometimes arranged in clusters, and a superficial perivascular and interstitial cell infiltrate. 61 The infiltrate contains lymphocytes, neutrophils, and sometimes eosinophils. 61 Inflammatory cells often extend into the walls of the superficial dermal vessels, as seen in vasculitis, but there is no fibrin extravasation. Less constant features include irregular epidermal acanthosis, edema of the papillary dermis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and nuclear ‘dust’ in the vicinity of the blood vessels. 61 Focal parakeratosis, containing neutrophils and serum, may also be present.

The streptococcal toxic shock syndrome is caused by virulent strains of exotoxin-producing streptococci, almost always group A organisms such as Streptococcus pyogenes. 63 Recently, a few cases due to group B streptococci have been reported. 64 It often occurs in the setting of deep soft tissue infections, when the portal of entry of the organism appears to be through the skin, but it may complicate burns, surgical wounds, or childbirth. Accordingly it can be seen in several clinical situations such as the young, the immunocompromised, the elderly, and diabetics. Rarely, it has developed in patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. 30

Clinically there is fever, pain at the site of the deep tissue infection, and skin necrosis and bullae. Renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation may occur. 65 A scarlatiniform rash may be present. A streptococcal bacteremia is present in 60% of cases, in contrast to the negative blood cultures in the staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome. 56 The mortality rate is usually as high as 30%; 64 it was 62% in a Chinese outbreak in 2005. 65

Prompt treatment with antibiotics should be undertaken. High dose penicillin G is usually effective, but antibiotics with a broader spectrum are usually commenced first, as the diagnosis may be in doubt.

The changes resemble those in ecthyma gangrenosum (see below). The deep soft tissue lesions, if present, are those of necrotizing fasciitis (see p. 552).

Perianal streptococcal dermatitis, caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococci, has been described almost exclusively in children, although a few adult cases have been reported.66.67. and 68. It presents as perianal erythema with a clearly defined border followed by a desquamating scale and subsequent healing. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, are uncommon69 in contrast to toxin-mediated perineal erythema which occurs abruptly after a bacterial pharyngitis due to Staph. aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.30. and 70. It can occur not only in young adults but also in childhood. 71

Ecthyma is a deeper pyoderma than impetigo and much less frequent. 18 It has a predilection for the extremities of children, often at sites of minor trauma, which allow entry of the causative bacteria. Group A streptococci, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes, are usually implicated, although coagulase-positive staphylococci are sometimes isolated as well.19. and 72. The lesions, which are sometimes multiple, consist of a dark crust adherent to a shallow ulcer and surrounded by a rim of erythema. Scarring usually results when the lesions heal. 19

Ecthyma gangrenosum is a severe variant of ecthyma seen in 5% or more of immunosuppressed individuals who develop a septicemia with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.73.74.75.76.77. and 78. A septicemia is not invariable. 79 It has also been seen in a harlequin baby, 80 and in previously healthy individuals. 81 It commences as an erythematous macule on the trunk or limbs: the lesion rapidly becomes vesicular, then pustular, and finally develops into a gangrenous ulcer with a dark eschar and an erythematous halo.82.83.84. and 85. Annular lesions are rare. 86 Periocular lesions have been reported in a diabetic patient. 87 Constitutional symptoms are usually present. Patients with solitary lesions have a better prognosis than those with multiple lesions. Similar necrotic ulcers have been reported in association with Aspergillus, Candida, 88 and Exserohilum89 infection, Morganella morganii, 90Citrobacter freundii, 91Chromobacterium violaceum, 92 candidosis, and following pseudomonas folliculitis (but usually without septicemia), 73 and cutaneous infections treated with antibiotics. 93Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia may result in the development of pustules, 94 bullae, 95 intertrigo, 96 or of a nodular cellulitis97 rather than ecthyma gangrenosum. 98 It needs to be distinguished from purpura fulminans in which disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) accompanies the infection (see p. 199).99.100. and 101.

In ecthyma there is ulceration of the skin with an inflammatory crust on the surface. There is a heavy infiltrate of neutrophils in the reticular dermis, which forms the base of the ulcer. Gram-positive cocci may be seen within the inflammatory crust.

Ecthyma gangrenosum shows necrosis of the epidermis and the upper dermis, with some hemorrhage into the dermis. 82 The epidermis may separate from the dermis. A mixed inflammatory-cell infiltrate surrounds the infarcted region. In some cases there is a paucity of inflammation.82. and 83. A necrotizing vasculitis with vascular thrombosis is present in the margins. 97 Numerous Gram-negative bacteria are usually present between the collagen bundles, and sometimes in the media and adventitia of small blood vessels.

Cellulitis is a diffuse inflammation of the connective tissue of the skin and/or the deeper soft tissues.19.102. and 103. It is therefore a deeper pyoderma than impetigo and some cases of ecthyma, although ecthyma gangrenosum could be included in this category. Clinically, cellulitis presents as an expanding area of erythema, which is usually edematous and tender. 104 Necrosis and hemorrhage sometimes supervene.105.106.107. and 108. In the past, these infections were usually caused by β-hemolytic streptococci and/or coagulase-positive staphylococci.19. and 109. A diverse range of organisms is now implicated in the causation of cellulitis.102.110.111.112.113.114.115.116.117.118. and 119. The injection of ricin in a suicide attempt resulted in a septic and toxic cellulitis in one patient. 120 Neutropenic and leukemic patients are now being seen with erythematous nodules on the leg caused by the opportunistic pathogen Stenotrophomonas (Xanthomonas) maltophilia.121.122. and 123. This organism has also resulted in digital necrosis in an immunocompetent farmer. 124 Pyogenic sporotrichoid lymphangitis is a rare presentation. 125 Lower extremity cellulitis appears to be increased in patients who have undergone saphenous venectomy for coronary artery bypass graft surgery,126. and 127. but it is also seen in chronic venous insufficiency, and obesity. 128 Gangrenous cheilitis has been reported in a child with myeloperoxidase deficiency. 129 Facial cellulitis may occur secondary to a dental abscess. 130

Many different clinical variants of cellulitis have been reported, some with overlapping clinical features and causative bacteria. 104 This has led to a proliferation of terms for these different variants. The term ‘gangrenous and crepitant cellulitis’ has been used for a subset with prominent skin necrosis and/or the discernible presence of gas in the tissues.105. and 131. The term ‘hemorrhagic cellulitis’ has also been used for this group, which includes progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene. It has been suggested that TNF-α is responsible for the damage to keratinocytes and vascular endothelium. 132 Subcutaneous and/or dermal abscesses are another manifestation of deep infection by various bacteria.133.134.135.136.137.138.139.140.141. and 142.

The cellulitides are characterized histopathologically by an infiltrate of neutrophils throughout the dermis and/or the subcutaneous tissue, with variable subepidermal edema and vascular ectasia. In those variants with necrosis there is usually a necrotizing vasculitis, which may be associated with fibrin thrombi in the lumen.143. and 144. Bacteria are often numerous in the group with necrosis, although usually only a few can be isolated in the other variants. 145

Treatment will usually depend on the antibiotic sensitivity of the causative organism. An increasing problem, of particular interest to dermatologists, is the emergence of community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus, which can be highly virulent.146.147.148. and 149. This form of infection is now an increasingly common condition among athletes. 150 It usually presents as skin and soft-tissue infections, especially abscesses. 151 Many such abscesses respond to drainage alone, but some will require antibiotic therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is an inexpensive and effective choice for many such patients. 151 It may be used with rifampin. 152 Resistance is emerging to the fluoroquinolones. 151

Erysipelas is a distinctive type of cellulitis which has an elevated border and spreads rapidly.19.153. and 154. It is more common in males, and most prevalent in patients 65 years and older. 155 Whereas the incidence of bacterial cellulitis of the leg in the United States was reported to be 6.62 per 1000 in 2004, erysipelas was much less common (0.14 per 1000). 156

Vesiculation may develop, particularly at the edge of the lesion. An uncommon bullous variant, usually confined to the lower legs, has been described. 157 The condition occurs particularly on the lower extremities, and less commonly on the face.158. and 159. Underlying diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease or lymphedema may be present. 158 Erysipelas may complicate the upper limb lymphedema that follows the treatment of breast cancer. 160 The causative group A streptococci,103. and 161. or other organisms,162. and 163. gain entry through superficial abrasions. It is associated with pain, swelling, and fever. Bacteremia is common. 19 Osteoarticular complications are not uncommon. 164

An erysipelas-like erythema, usually on the lower legs, is seen in familial Mediterranean fever, an autosomal recessive disease affecting certain ethnic groups. 165 The histopathology has features more in keeping with a neutrophilic dermatosis than erysipelas.

The term pseudoerysipelas has been given to a recurrent hemolysis-associated erythematous eruption of the lower legs in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis. 166 No infection was present. 166

Treatment of erysipelas is usually with β-lactam antibiotics but macrolides are the second choice. 155 Benzathine penicillin G, intramuscularly at 14-day intervals, has been used as prophylactic antibiotherapy in patients who have experienced recurrent erysipelas in lymphedematous upper limbs following the treatment of breast cancer. 160 Long-standing treatment for lymphedema of the lower limbs is essential in order to prevent recurrence of erysipelas and aggravation of the pre-existing lymphatic impairment. 167

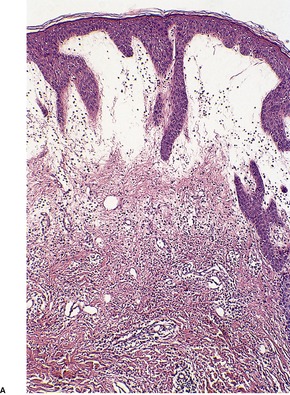

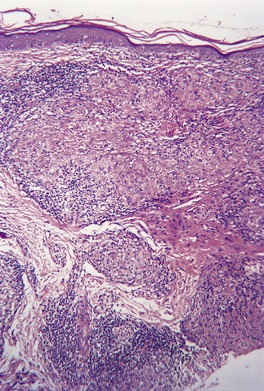

There is marked subepidermal edema, which may lead to the formation of vesiculobullous lesions. Beneath this zone there is a diffuse and usually heavy infiltrate of neutrophils, but abscesses do not form. The infiltrate is sometimes accentuated around blood vessels. There is often vascular and lymphatic dilatation. In healing lesions the dermal infiltrate diminishes, and granulation tissue may form immediately below the zone of subepidermal edema (Fig. 23.3). Direct immunofluorescence has been used to confirm the streptococcal etiology of most cases of erysipelas. 161

Erysipelas. (A) Acute lesion with marked subepidermal edema. (B) This healing lesion shows little inflammation in the upper dermis. (H & E)

Erysipeloid is an uncommon infection, usually found on the hands, which clinically resembles erysipelas. 168 The causative organism, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, is a contaminant of dead organic matter, and infection with this organism is an occupational hazard for fish and meat handlers. 169 The incubation period varies from 1 to 7 days after inoculation. 170 Less commonly, multiple cutaneous lesions or systemic spread of the organism may occur. Erysipeloid-like eruptions have been reported in several patients receiving chemotherapy with gemcitabine. 171

Treatment of erysipeloid with penicillin for 7–10 days results in dramatic improvement.169. and 170.

There is usually massive edema of the papillary dermis overlying a diffuse and polymorphous infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and variable numbers of neutrophils. Sometimes there is spongiosis of the epidermis, leading to intraepidermal vesiculation. Organisms are not demonstrable in tissue sections, even with a Gram stain, possibly because they are present in the L form (without a cell wall). 168

Blistering distal dactylitis is an uncommon yet distinctive infection localized to the volar fat pad of the distal phalanx of the fingers.19.172.173.174. and 175. Group A streptococci are usually implicated, although rarely other organisms have been isolated.176. and 177. The blistering results from massive subepidermal edema.

In addition to its use as a synonym for deep pyogenic infection (see above), the term ‘cellulitis’ is sometimes used in a more restricted sense for spreading inflammation of the cheek,178.179. and 180. periorbital area181. and 182. or the perianal region,174.183.184.185. and 186. or in the margins of wounds, 19 or injecting sites. 187 The lesions lack the distinct border of erysipelas. 19 Various organisms have been implicated as the cause of this condition, 188 including Staph. aureus in patients with HIV infection, 189Haemophilus influenzae type b in the case of facial lesions,179. and 190. and Vibrio vulnificus in some infections of the extremities.191.192.193.194.195.196.197. and 198. The latter organism can produce various lesions, including septicemia, hemorrhagic bullae,199. and 200. cellulitis, and necrotizing fasciitis. 201Pasteurella multocida has been implicated in the wound infection and cellulitis that may follow animal bites. 202Vibrio cholerae (non-01 type) can rarely produce a cellulitis or infect a pre-existing wound.203. and 204. Escherichia coli has also been implicated, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. 205 Varicella infection is complicated, rarely, by a cellulitis resulting from group A β-hemolytic streptococci or Staph. aureus. 206

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare and distinct form of cellulitis that rapidly progresses to necrosis of the skin and underlying tissues.207.208.209.210.211.212.213.214. and 215. It occurs mostly in adults but cases in children have been reported. 216 The term ‘flesh-eating bacteria’ has appeared in the media, highlighting the progressive necrotizing nature of the disease. 217 It involves tissues at a deeper level than erysipelas, and may spread into the underlying muscle. 218 Necrotizing fasciitis commences as a poorly defined area of erythema, usually on the leg, 207 or perineal region. 219 Bilateral periorbital involvement has been recorded. 220 Serosanguineous blisters develop and subsequently necrosis occurs at their center.221. and 222. It often follows a penetrating injury. Uncommonly, the condition follows surgery; 223 in one case it followed mosquito bites. 224 There may be underlying diabetes, alcoholism, or some other immune system deficiency.225. and 226. There is a strong association with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). 227 It may occur in intravenous drug users.228. and 229. Constitutional symptoms may be present, and there is a significant mortality. 218 The term ‘streptococcal toxic shock syndrome’ has been applied to this systemic illness, 230 although it more properly refers to a discrete entity with some similarity to the toxic shock syndrome of staphylococcal origin (see p. 550). 30 Various organisms have been isolated,231.232. and 233. particularly group A streptococci.222.234.235. and 236. Often the infection is polymicrobial.216. and 237. A zygomycete has also been isolated from this condition. 238 Rapid diagnosis kits are available to confirm cases of streptococcal origin. Protein S deficiency may be responsible for the necrosis in some cases. 239

Immediate treatment of necrotizing fasciitis with penicillin, if group A streptococci are involved, or with clindamycin plus cefoperazone sodium if the organism is not known, is recommended once a diagnosis is made, together with surgical debridement. 216 The antibiotics should then be tailored to the sensitivity of any organism(s) cultured. 235

Fournier’s gangrene of the scrotum is a closely related entity.221. and 240. It is usually found in elderly men, with an underlying disease such as diabetes. Cases have been reported in younger persons. 241 It is a rare complication of the use of all-trans-retinoic acid as induction therapy in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Its response to corticosteroids suggests that Fournier’s gangrene is a localized vasculitis and represents a local Schwartzmann phenomenon. 242 Enterobacteria are common isolates, although a mixed growth is often seen.243. and 244. In one recent series the mortality was nearly 10%. 243 Treatment of Fournier’s gangrene includes fluid resuscitation, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics until the antibiotic sensitivities of the organism(s) are known, and surgical debridement of necrotic tissue. 240

Necrotizing fasciitis is a form of septic vasculitis with inflammation of the walls of vessels, sometimes associated with occlusion of the lumen by thrombi. 144 There is a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the viable tissues bordering the areas of necrosis. The necrosis involves the epidermis, dermis, and upper subcutis.

There are several rare but distinct clinicopathological entities that belong to the category of deep pyogenic infections. They include clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene), progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene, and erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp, legs, and other sites. They will be discussed in turn.

Clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene) is associated with muscle and soft tissue necrosis. Cutaneous lesions, including bullae and necrosis, may overlie the deeper lesions. The usual causative organisms in gas gangrene are clostridial species; non-clostridial cases are infrequently reported. 245 Wound botulism has been reported in black tar heroin users. 246 Large Gram-positive bacilli are usually present in the affected tissues. 105 A bacterium related to the genus Clostridium – Bacillus piloformis – has produced localized verrucous lesions in a patient infected with HIV-1. 247Bacillus cereus infection has been associated with a single necrotic bulla in a patient with a lymphoma. 248

Treatment includes the immediate surgical debridement of damaged tissue and the use of antibiotics such as penicillin in high doses. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is also effective but it should not delay the other measures already mentioned.

Progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene is characterized by indurated ulcerated areas with a gangrenous margin, usually developing in operative wounds.105. and 249. This condition, also known as Meleney’s ulcer, is often associated with a mixed growth of peptostreptococci and Staph. aureus or enterobacteriaceae. 105

Erosive pustular dermatosis is an uncommon disorder of the elderly, involving predominantly the sun-damaged scalp. It presents with widespread erosions and crusted sterile pustules, leading to scarring alopecia.250.251. and 252. Intact pustules are rarely present, despite the name. 253 A clinically similar rash has been reported on the legs, particularly in a background of chronic venous stasis.253.254. and 255. Lesions on the face and other body sites have also been reported, and it has been suggested that chronic, non-healing, shallow erosions on actinically damaged, or otherwise atrophic skin are related conditions. The condition has a female predominance and most affected individuals are over 65 years of age; it has also been reported in a 15-year-old boy, 253 and in infants. 256

Its exact nosological position is uncertain, but there are some morphological similarities to blastomycosis-like pyoderma (see below). Trauma, previous herpes zoster infection, recent cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil application, radiation therapy, and surgery have all been implicated as predisposing factors.253.257.258.259.260.261. and 262. Cases in infants may follow perinatal scalp injury. 256Staph. aureus is sometimes isolated, but these organisms may be secondary invaders. 250Amicrobial pustulosis associated with autoimmune diseases is probably part of the spectrum. It may involve the scalp as well as the flexures. It has responded to zinc therapy. 263

Treatment with potent topical corticosteroids is frequently used. Topical tacrolimus ointment and calcipotriol (calcipotriene) cream can also be used. Oral zinc sulfate and isotretinoin have been tried in some cases.264.265. and 266. The lesions do not respond to topical or oral antibiotics. 256

The skin is usually ulcerated, but intact atrophic epidermis may cover other involved areas. In such cases there is exocytosis of inflammatory cells. There is variable crusting overlying ulcerated skin and atrophic areas. Intact pustules are rarely seen. The dermal infiltrate is moderate to marked, and consists of lymphocytes and variable numbers of plasma cells. Scarring is progressive. There may be a few foreign body giant cells in areas of follicular destruction. 264

Blastomycosis-like pyoderma is an unusual form of pyoderma that presents with large verrucous plaques studded with multiple pustules and draining sinuses.267. and 268. There may be an underlying disturbance of immunological function in some cases.268. and 269. A variant of this condition is found in subtropical areas of Australia in the actinically damaged skin of the elderly, particularly on the forearm.270. and 271. This has been known as ‘coral reef granuloma’, on the basis of its clinical appearance. 272 Actinic comedonal plaque, in which plaques and nodules with a cribriform appearance develop in sun-damaged skin, 273 appears to be the end-stage of a similar but milder inflammatory process.270. and 271. Similar lesions have been reported at the margins of tattoos.270. and 274. Actinic comedonal plaque has also been regarded as an ectopic form of the Favre–Racouchot syndrome (see p. 342). 275

Bacteria, particularly Staph. aureus and species of Pseudomonas and Proteus, have been isolated from biopsies.268.270.276. and 277. Sun-damaged skin is known to diminish local immune responses, and this factor is probably important in the variant found in Australia.278. and 279.

Response to antibiotics such as oral doxycycline is often poor, despite in-vitro susceptibility of the organism to tetracyclines. 280 Minocycline has also been used. Local ablative measures such as curettage and cautery, carbon dioxide laser, or cryotherapy may be used if surgical excision is unsuitable. 281 Low-dose oral acitretin for 3–4 months has been used successfully. 280

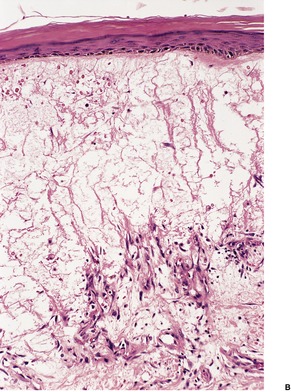

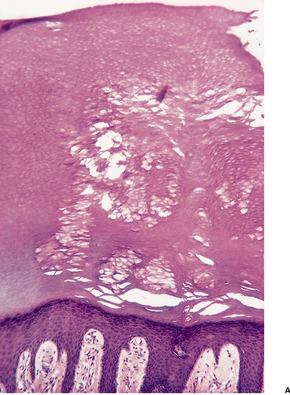

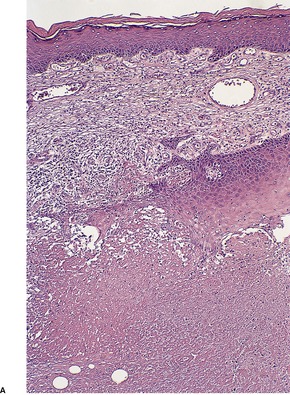

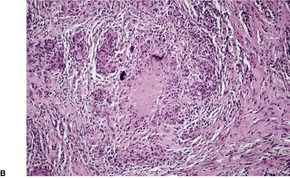

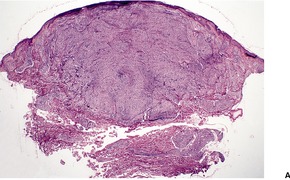

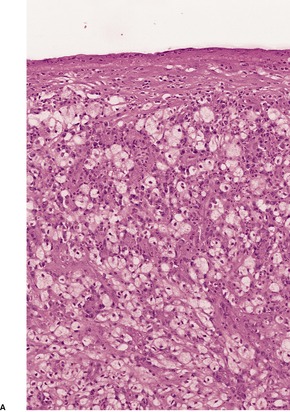

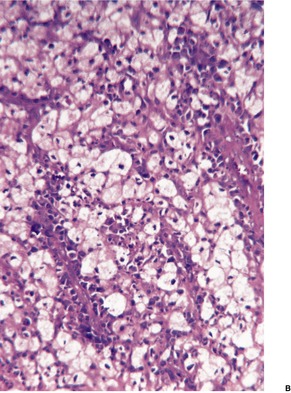

There is a heavy inflammatory infiltrate throughout the dermis, with multiple small abscesses set in a background of chronic inflammation (Fig. 23.4). 268 A few granulomas are occasionally present, but these are usually related to elastotic fibers. There is prominent pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which in some areas appears to result from hypertrophy of the follicular infundibulum. Intraepidermal microabscesses are present, and these probably represent the attempted transepidermal elimination of the dermal inflammatory process. Solar elastotic fibers are present in the variants known as ‘coral reef granuloma’ and ‘actinic comedonal plaque’. 273 There may be some dermal fibrosis in healing lesions, although actinically damaged fibers usually persist in the upper dermis.

Blastomycosis-like pyoderma. (A) There is dermal suppuration adjacent to enlarged follicular structures which become draining sinuses. (B) Suppurative granulomas are often present. (H & E)

The corynebacteria are a diverse group of Gram-positive bacilli which include Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the causative organism of diphtheria, as well as a bewildering number of species that are found on the skin as part of the normal flora and which defy classification. 282 These latter organisms are usually referred to as diphtheroids or coryneforms. Certain strains have the ability to produce malodor of the axilla. 283 Three skin conditions appear to be related to an overabundance of these coryneforms: erythrasma, trichomycosis, and pitted keratolysis. 282 Interestingly, the three have been reported to coexist in some individuals.284. and 285. Rarely, other species of corynebacteria have been incriminated as a source of infection in diabetics286 or immunocompromised patients, the most important being the JK group (C. jeikeium).287. and 288. These organisms have been found in patients with heart prostheses and endocarditis, and recently as a cause of cutaneous lesions in immunocompromised patients. 287 They may produce a histological picture mimicking botryomycosis (see p. 602). 288

Topical sodium fucidate has been used to treat cutaneous disease. 285 Oral erythromycin can be used for more extensive infections. 285

Cutaneous diphtheria is a rarely diagnosed entity which is still found very occasionally in tropical areas.289.290. and 291. The typical lesion is an ulcer with a well-defined irregular margin; the base is covered with a gray slough. Systemic effects, from the absorption of exotoxin, and severe lymphadenitis may develop. Cutaneous carriers also occur.

The treatment of diphtheria requires the administration of a specific antitoxin as soon as the diagnosis is made, and the use of penicillin or erythromycin.

There is necrosis of the epidermis and varying depths of the dermis. The base of the ulcer is composed of necrotic debris, fibrin, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. The bacilli are often difficult to see in tissue sections.

Erythrasma, caused by a diphtheroid bacillus Corynebacterium minutissimum, presents as well-defined, red to brown finely scaling patches with a predilection for skin folds, particularly the inner aspect of the thigh just below the crural fold.292.293. and 294. A rare generalized disciform variant has been reported. 294 This organism has been cultured from granulomatous nodules on the leg in an HIV-infected man. 295 Erythrasma is a not uncommon asymptomatic infection in the obese, and in diabetics and patients in institutions, particularly in humid climates.292. and 293. Examination of affected skin under a Wood’s ultraviolet lamp shows a characteristic coral-red fluorescence (because of the presence of porphyrins).

The treatment of erythrasma involves the topical application of one of the imidazole antifungal agents such as clotrimazole, ketoconazole, or miconazole. Whitfield’s ointment has been used for interdigital lesions. Erythromycin can be used for extensive or recurrent cases.

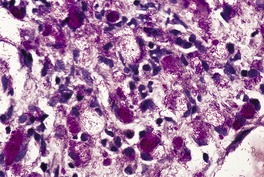

The biopsy often appears normal when hematoxylin and eosin preparations are examined, erythrasma being an example of a so-called ‘invisible dermatosis’. Small coccobacilli can be seen in the superficial part of the stratum corneum in Gram preparations. They are also seen in PAS (periodic acid–Schiff) and methenamine silver preparations (Fig. 23.5).

Erythrasma. Minute organisms can be seen in the stratum corneum. There is no inflammatory response. (Periodic acid–Schiff)

Electron microscopy has confirmed the bacterial nature of erythrasma. It has also shown decreased electron density in keratinized cells, with dissolution of normal keratin fibrils at sites of proliferation of organisms.298. and 299.

Trichomycosis is a bacterial infection of axillary hair (trichomycosis axillaris) and, uncommonly, pubic hair (trichomycosis pubis).300. and 301. There are usually pale yellow concretions attached to the hair shaft: these are large bacterial colonies. Sometimes the casts are red, and rarely they are black. 301 They may be the source of an offensive odor. The causative organism was originally designated as Corynebacterium tenuis, but it now seems that at least three species are involved.301. and 302. The infecting bacteria are generally believed to produce a cement-like substance which they use to adhere to the hair shaft and to form the large concretions; 301 this traditional view has been challenged, 303 and it has now been suggested that the sheath substance in which the organisms are embedded is apocrine sweat. 303 Sometimes the bacteria invade the superficial hair cortex. 304 Trichomycosis must be distinguished from other extraneous substances attached to the hair shaft.

The use of an antiperspirant will usually control the disease. If there is a heavy growth of organisms on the hairs, clipping followed by the application of a topical antibacterial agent will hasten resolution.

Pitted keratolysis is characterized by multiple asymptomatic pits and superficial erosions on the plantar surface of the feet, particularly in pressure areas.305.306.307.308.309. and 310. Rarely, the palms are involved.306.311. and 312. It occurs predominantly in young adults; there is a male predominance. 313 Sometimes there is brownish discoloration of involved areas, giving them a dirt-impregnated appearance. 314 Pitted keratolysis is more common if the feet are moist from hyperhidrosis or because the climate is hot. 315 It is often associated with the wearing of occlusive and protective shoes. 313 Malodor is common. 310 The pits are thought to result from the keratolytic activity of species of Corynebacterium, but Dermatophilus congolensis307. and 316. and Micrococcus sedentarius317 have also been incriminated.

As with erythrasma, the topical application of one of the imidazole antifungal agents is usually effective. Fucidin ointment has also been used. Any excess sweating should be appropriately controlled.

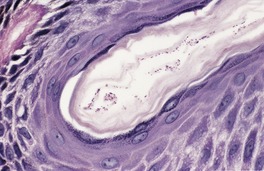

The pits appear as multiple crateriform defects in the stratum corneum. In early lesions there are areas of pallor within the stratum corneum (Fig. 23.6). In the base and margins of the pits there are fine filamentous and coccoid organisms that are Gram-positive and argyrophilic with the methenamine silver stain. It has been suggested that two types of pitted keratolysis can be distinguished histologically. 318 In the superficial or minor type there is only a small depression due to focal lysis. Coccoid bacteria are found on the surface of the stratum corneum. In the classical or major type the organisms exhibit dimorphism with septate ‘hyphae’ as well as coccoid forms, which extend into the stratum corneum forming more definite pits. 318

Pitted keratolysis. (A) The stratum corneum adjacent to an area of pitting shows zones of pallor corresponding to foci containing the causative organisms. (H & E) (B) They can be seen in the pale areas of the stratum corneum using silver stains. (Silver methenamine)

Primary infections of the skin by Neisseria meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae are rare because these organisms are unable to penetrate intact epidermis. However, cutaneous lesions do occur quite commonly in meningococcal and gonococcal septicemia; they take the form of a vasculitis (see Ch. 8, p. 213).

Cutaneous lesions, which may take the form of erythematous macules, nodules, petechiae, or small pustules, occur in 80% or more of acute meningococcal infections (see p. 213). Features of disseminated intravascular coagulation are invariably present. Chronic meningococcal septicemia is comparatively rare; it is characterized by the triad of intermittent fever, arthralgia, and vesiculopustular or hemorrhagic lesions of the skin. The hemorrhagic lesions are usually a manifestation of purpura fulminans, which develops in 15–25% of those with meningococcemia. 320 It is a predictor of poor outcome. 320 Chronic meningococcemia is a rare complication in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. 321 A N. meningitidis-specific PCR assay is available for testing skin biopsy specimens in suspected chronic meningococcemia. 322

The cutaneous lesions in meningococcal septicemia show an acute vasculitis, with fibrin thrombi in the small blood vessels of the dermis and extravasation of fibrin. There are neutrophils in and around the vessels, but the infiltrate is not as heavy as it is in hypersensitivity vasculitis. Leukocytoclasis is not usually a conspicuous feature.

In pustular lesions of chronic meningococcemia there are intraepidermal and subepidermal collections of neutrophils. A vasculitis is present in the dermis; the infiltrate contains some lymphocytes in addition to neutrophils.

Urethritis (gonorrhea) is the usual manifestation of infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. There is now a high incidence of this disease among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. 323 This sexually transmitted disease may also infect the accessory glands of the vulva and the median raphe of the penis. 324 Primary infections of extragenital skin are very rare, although pustular lesions on the digits have been reported. 325 Cases of non-gonococcal urethritis due to species of Mycoplasma are not uncommon. The macrolide antibiotics appear to be more effective than tetracyclines in this group of infections. 326

Gonococcal septicemia, both acute and chronic, may result in a cutaneous vasculitis; the lesions resemble those seen in meningococcal septicemia (see above).327. and 328.

First-line treatment for gonorrhea depends very much on the antibiotic susceptibility of the organism, in a particular region. In parts of Europe, resistance to ciprofloxacin exceeds 50%. 329 Antibiotics such as cefixime, ceftriaxone, spectinomycin, and in some cases azithromycin or ciprofloxacin have been used. 329

Primary pustular lesions on the penis or extragenital skin are usually ulcerated, with a heavy inflammatory cell infiltrate in the underlying dermis. There are numerous neutrophils, often forming small abscesses. Gram-negative intracellular diplococci can usually be found in tissue sections, but they are more easily found in smears made from the purulent exudate on the surface of the lesion.

In gonococcal septicemia the cutaneous lesions resemble those seen in meningococcal septicemia (see above); the appearances are those of a septic vasculitis (see p. 213).

The cutaneous mycobacterioses include leprosy and tuberculosis, as well as a diverse group of infections caused by various environmental (atypical, non-tuberculous) mycobacteria. Within these three categories there are clinicopathological variants which are sometimes given the status of distinct entities; for example, infections by Mycobacterium ulcerans and M. marinum (Buruli ulcer and swimming pool granuloma, respectively) are often considered separately from infections caused by other non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria.

Established mycobacterial infections generally give rise to a granulomatous tissue reaction, although considerable variability exists in the histopathological appearances of individual lesions. 330 These aspects will be considered further below.

Tuberculosis of the skin has been declining in incidence all over the world, although it is still an important infective disorder in India and parts of Africa.331.332.333.334. and 335. The epidemic of HIV/AIDS in parts of Africa has been followed by an epidemic of tuberculosis in its wake. 336 It has been estimated that nearly eight million new cases of tuberculosis occur in the world each year. 337 Cutaneous tuberculosis is a relatively rare manifestation of tuberculosis accounting for only 0.14% of all reported cases. 338 With the eradication of tuberculosis in cattle, human infections with Mycobacterium bovis are rarely seen these days.339.340. and 341. Accordingly, cutaneous tuberculosis can be categorized into two major etiological groups: infections caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and those caused by non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria. Infections by non-tuberculous mycobacteria will be considered separately. In some of the so-called ‘developed countries’, such infections are more numerous than those caused by M. tuberculosis.

Not all individuals exposed to M. tuberculosis become infected. There is a complex interaction between the organism, the environment, and the host. 342 Corticosteroids may upset this balance leading to the reactivation of non-active disease. 343 The increasing use of biological therapies for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases, particularly psoriasis, has also led to an increase in tuberculosis. 344 Genetic susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (OMIM 607948) involves many genes. One such gene maps to chromosome 2q35, which includes the NRAMP1 gene (natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1), 342 and the MTBS1 gene. Another TB susceptibility locus is found at chromosome 8q12–q13. X-linked susceptibility has also been proposed. Patients with hypomorphic mutations of the nuclear factor κB essential modulator gene may also have increased susceptibility to mycobacterial disease. 345 A review on the genetically determined susceptibility to mycobacterial infection was published in 2008. 346 The review discussed in detail the genetic abnormalities in the interleukin 12 (IL-12) dependent, high output interferon-γ (IFN-γ) pathway that result in increased susceptibility to infection. 346

Infections with M. tuberculosis have traditionally been classified into primary tuberculosis, when there has been no previous exposure to the organism, and secondary tuberculosis, resulting from reinfection with the tubercle bacillus. 331 Reinfection (secondary) tuberculosis of the skin is subdivided on the basis of various clinical features into lupus vulgaris, tuberculosis verrucosa, scrofuloderma, orificial tuberculosis, and disseminated cutaneous tuberculosis. 347 The tuberculids are a further category and were thought to represent a cutaneous reaction to a tuberculous infection elsewhere in the body, there being no detectable bacilli in the tuberculid skin lesions by conventional techniques.

This traditional classification has been disparaged somewhat, and a classification based on the presumed route of infection has been proposed.348. and 349. Several modifications have already been suggested, but its basic format remains as follows:350.351. and 352.

• infections due to inoculation from an exogenous source

• infections from an endogenous source, both contiguous (scrofuloderma in the traditional classification) and from autoinoculation (orificial tuberculosis)

• infections resulting from hematogenous spread.

The last of these three categories can be further subdivided into lupus vulgaris, acute disseminated tuberculosis, and the formation of cutaneous nodules or abscesses.

This relatively new system of classification has the advantage of applying to infections with atypical mycobacteria as well as those caused by M. tuberculosis. However, it still requires assumptions to be made when an attempt is made to classify an individual case. Furthermore, as infections with certain atypical mycobacteria (Buruli ulcer and swimming pool granuloma) are established clinical entities, it seems unlikely that this new classification will offer many advantages over the traditional one. Such has been the case. It should also be emphasized that cases occur which defy classification by any means, and it is quite appropriate to diagnose ‘cutaneous tuberculosis’ in these cases, pending the completion of cultural identification (if obtained).347. and 353. Various automated techniques, using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), now provide a rapid and specific method for the identification of M. tuberculosis from tissue samples.354.355.356.357.358.359. and 360. However, despite general enthusiasm for this technique,361.362.363.364.365.366.367. and 368. several studies have concluded that PCR was not of much use in paucibacillary forms of cutaneous tuberculosis, particularly using paraffin-embedded tissue.369. and 370. Two commercially available interferon-γ release assays (IGRAs) are now being used in place of tuberculin skin tests for the detection of asymptomatic infections. 371M. tuberculosis has also been identified by PCR in some cases of sarcoidosis. 372

Any classification of cutaneous tuberculosis should also make provision for the complications of BCG vaccination. 373 These include local abscesses and secondary bacterial infections, lupus vulgaris,374.375. and 376. lichen scrofulosorum, 377 lymphadenitis, tuberculids, 378 scrofuloderma-like lesions,379. and 380. and local keloid formation. 381 Granulomatous nodules have developed at the injection site following a long period of latency.382. and 383. Fatalities have been recorded following BCG vaccination of individuals who are immunocompromised and develop disseminated disease.384.385.386.387.388. and 389. There is also a genetic predisposition to disseminated disease following BCG vaccination. It is closely related to the genetic abnormalities associated with atypical mycobacteriosis (see below).

The histological pattern of the BCG test site may be erythema multiforme-like, basal spongiotic in type, or have a non-specific perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes. If active tuberculosis is present, the test site frequently has the more severe erythema multiforme-type reaction, sometimes with bulla formation. 390

Of interest is the recent use of polyclonal anti-Mycobacterium bovis antibodies to detect bacterial and fungal microorganisms in paraffin-embedded tissue. 391 This technique is particularly useful in cases with only small numbers of organisms.

The following classification will be followed here:

• primary tuberculosis

• lupus vulgaris

• tuberculosis verrucosa

• scrofuloderma

• orificial tuberculosis

• disseminated cutaneous tuberculosis

• tuberculids.

In a series of 153 cases with cutaneous tuberculosis reported from Pakistan, 41.2% had lupus vulgaris, 35.3% scrofuloderma (mainly children), and 19% tuberculosis verrucosa. 392

Primary (inoculation) tuberculosis of the skin is the cutaneous analogue of the pulmonary Ghon focus.393. and 394. One to three weeks after introduction of the organism by way of a penetrating injury, a red indurated papule appears.395.396.397.398.399.400. and 401. This subsequently ulcerates, forming a so-called ‘tuberculoid chancre’. Ulcerated lesions may also be a manifestation of secondary (reinfection) tuberculosis, 402 when the source of infection may be endogenous or from inoculation, although secondary inoculation tuberculosis usually presents as tuberculosis verrucosa (see below). 403 Sporotrichoid lesions have developed following a primary inoculation lesion. 404 Regional lymphadenopathy usually develops in primary tuberculosis.

Primary tuberculosis may be associated with tattooing,395. and 405. ritual circumcision, nose piercing, 406 inoculation of homeopathic solutions, 407 or injury by contaminated objects408 to laboratory workers, surgeons, or to prosectors.393.409. and 410. Sometimes no obvious source of infection can be identified, particularly in children.411. and 412. Atypical (non-tuberculous) mycobacteria are now implicated more often than M. tuberculosis in the etiology of primary tuberculous infection of the skin.

Early lesions show a mixed dermal infiltrate of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. This is followed by superficial necrosis and ulceration. After some weeks tuberculoid granulomas form, and these may be accompanied by caseation necrosis. 347 Acid-fast bacilli are usually easy to find in the early lesions, but there are very few bacilli once granulomas develop.

Lupus vulgaris is the most common form of reinfection tuberculosis, occurring predominantly in young adults.413. and 414. There is one report of its occurrence in siblings. 415 It is caused almost exclusively by M. tuberculosis although rare reports implicating the M. avium-intracellulare complex, M. fortuitum, 416 and M. bovis have been published.339.417.418. and 419. It has followed BCG vaccination,376.420.421. and 422. and also tattoo inoculation. 423 Lupus vulgaris affects primarily the head and neck region, 424 although in southeast Asia it appears to be more common on the extremities and buttocks.425.426.427. and 428. Penile involvement can occur. 429 Lesions involving the nose and face can be destructive. Alopecia often develops in lesions of the scalp. 430 The usual picture is of multiple erythematous papules forming a plaque, which on diascopy shows small ‘apple jelly’ nodules.431. and 432. Crusted ulcers, local cellulitis, 433sporotrichoid lesions,434. and 435. ‘turkey-ear’ lesions, 436 and dry verrucous plaques are sometimes seen. 425 It may develop within a scar, 437 or following tattooing. 438 The disease runs a chronic course and may result in significant scarring. Late complications include the development of contractures, lymphedema, squamous carcinoma330.348.439.440.441. and 442. and, rarely, basal cell carcinoma, 443 malignant melanoma, 444 and cutaneous lymphomas.445. and 446.

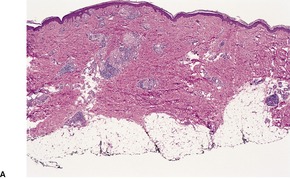

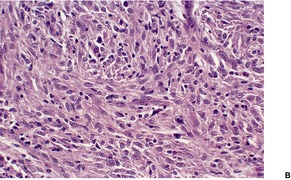

In lupus vulgaris there are tuberculoid granulomas with a variable mantle of lymphocytes in the upper and mid dermis. 413 The granulomas have a tendency to confluence (Fig. 23.7). Rarely they have a perifollicular arrangement. 447 Caseation is sometimes present. If prominent caseation is present in a facial lesion, granulomatous rosacea also needs consideration. 448 Multinucleate giant cells are not always numerous. Langerhans cells are present in moderate numbers in the granulomas. 449 The overlying epidermis may be atrophic or hyperplastic, but only rarely is there pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Transepidermal elimination of granulomas through a hyperplastic epidermis is rarely seen. 450 Bacilli are usually sparse and difficult to demonstrate in sections stained to show acid-fast organisms. 445 They can now be demonstrated using PCR.451. and 452. In one report, Michaelis–Gutmann bodies were present in macrophages in the infiltrate. 453 Variable fibrosis accompanies the lesions. Effective antituberculous therapy leads to a substantial reduction of fibrosis. 454

Lupus vulgaris. There are tuberculoid granulomas, with a tendency to confluence, throughout the dermis. (H & E)

Sometimes the histological appearances resemble sarcoidosis, with only a relatively sparse lymphocytic mantle around the granulomas: a consequent delay in making the correct diagnosis is common in such cases.348.455. and 456.

An atypical CD30+ lymphoid infiltrate has also been described. The infiltrate was eventually regarded as being of reactive type. 457

Tuberculosis verrucosa is an uncommon form of cutaneous tuberculosis resulting from inoculation of organisms into the skin in individuals with good immunity.458.459. and 460. It may occur as an occupational hazard in the autopsy room. A verrucous plaque forms on the back of the hand, elbows, or fingers.347.461.462.463. and 464. The lower extremities are more often involved in cases occurring in India and Hong Kong.331.465.466.467.468.469. and 470.

Scrofuloderma is tuberculous involvement of the skin resulting from direct extension from an underlying tuberculous lesion in lymph nodes or bone.332.471.472.473.474. and 475. The term has also been used, incorrectly, for cases with presumptive cutaneous inoculation. 476 The neck and submandibular region are the most common sites.477.478.479. and 480. Scrofuloderma usually presents as an undermined ulcer or discharging sinus, with surrounding induration and dusky red discoloration.332.347.481. and 482. Sporotrichoid lesions were present in one case. 435 Internal organs are often involved in this form of the disease. 483 In contrast, patients with organ tuberculosis uncommonly have cutaneous disease.484. and 485. Non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria are often responsible for this type of infection. It has been reported following BCG vaccination.379. and 380.

The epidermis is usually atrophic or ulcerated, an underlying abscess and/or caseation necrosis involving the dermis and subcutis. 347 At the periphery of the necrotic tissue there are granulomas. They have fewer lymphocytes than is usual in tuberculosis, suggesting a weak cell-mediated immune response. 486 Acid-fast bacilli can usually be found in smears taken from the affected area, although they are not always demonstrable in tissue sections. 332

Orificial tuberculosis is a rare form of cutaneous tuberculosis that presents as shallow ulcers at mucocutaneous junctions in patients with advanced internal (usually pulmonary) tuberculosis.357.487.488. and 489. It results from autoinoculation. 490 Perianal tuberculosis is a rare variant of orificial tuberculosis.491.492. and 493.

There is ulceration with underlying caseating granulomas and numerous acid-fast bacilli.

Disseminated cutaneous tuberculosis results from the dissemination of tubercle bacilli from pulmonary, meningeal, or other tuberculous foci, 494 particularly in children.478.495. and 496. There may be an underlying disturbance of the immune system predisposing to this widespread infection. 497The usual presentation is with papules, pustules, vesicles, and abscesses that become necrotic, forming small ulcers.338.347.497.498. and 499. Disseminated infection in patients with AIDS may take the form of multiple small pustules341 or erythematous papules. 500 As such, the cutaneous lesions may be a manifestation of more widespread miliary tuberculosis. 501

In early lesions there is focal necrosis and abscess formation, with numerous acid-fast bacilli, surrounded by a zone of non-specific chronic inflammation.347. and 497. In older lesions granulomas usually develop in this outer zone. In the pustular lesions seen in patients with AIDS, there are numerous neutrophils in the papillary dermis, with rare Langhans giant cells. 341

Tuberculids are a heterogeneous group of cutaneous lesions which occur in association with tuberculous infections elsewhere in the body, or in other parts of the skin,331.503.504. and 505. in patients with a high degree of immunity and allergic sensitivity to the organism. 506 Nevertheless, rare cases have been reported in patients with HIV infection. 507 Tuberculids may act as sentinel lesions of visceral tuberculosis, and their presence should initiate a search for overt or occult disease. 508 Tuberculids have also followed BCG vaccination. 378 Tuberculids are increasing in incidence in some countries. 509 Bacteria cannot be isolated from tuberculids, although M. tuberculosis DNA can be demonstrated in some cases using PCR.510. and 511. IGRAs (see above) have also detected latent tuberculous infection in tuberculids. 371 Response to antituberculous therapy has been recorded even in some cases in which no bacterial DNA could be detected.

The concept of tuberculids has been challenged from time to time, but they are usually considered to include erythema induratum–nodular vasculitis, lichen scrofulosorum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and nodular tuberculid;350. and 352. granulomatous phlebitis is possibly a fifth type (phlebitic tuberculid),512. and 513. although there are some similarities to nodular tuberculid. More than one type of tuberculid is sometimes present,514. and 515. and transformation from one type into another has been recorded. 516 Sometimes the tuberculid does not fit neatly into one of the current categories. One such case resembled generalized granuloma annulare. 517

Erythema induratum–nodular vasculitis.

This is a panniculitis (see p. 463) which presents with bluish-red plaques and nodules, with a predilection for the lower part of the legs, particularly the calves.518. and 519. The coexistence of this condition and papulonecrotic tuberculid has been reported. 520M. tuberculosis DNA has been recovered from lesional skin using a PCR technique. 521

Lichen scrofulosorum.

This tuberculid is characterized by asymptomatic, slightly scaly papules measuring 0.5–3 mm in diameter.522.523.524.525.526. and 527. They are often follicular in distribution, mainly affecting the trunk of children and young adults.523. and 528. Localization to the vulva is a rare event.529. and 530. Lichen scrofulosorum usually occurs in association with tuberculosis of bone or of lymph nodes, but it may be associated with tuberculous infection in other sites;522.523.531. and 532. rarely it may follow BCG vaccination, 377 or infection with M. avium, 533 or other non-tuberculous mycobacteria. 534 It sometimes appears during treatment of tuberculosis. 535

Papulonecrotic tuberculid.

This presents as dusky papules or nodules that sometimes undergo central necrosis and which leave varioliform scars on healing.536.537.538. and 539. There is a predilection for the extremities, although the ears and genital region may also be involved.540.541.542. and 543. A variant with verrucous lesions mimicking Kyrle’s disease has been described. 544 It is uncommon in children. 545 In one study, a focus of tuberculosis was identified elsewhere in the body in 38% of cases.518.546. and 547. The tuberculin test is usually strongly positive and the lesions respond to antituberculous drugs. Multidrug resistant strains of tuberculosis have been encountered. 548 In a number of cases M. tuberculosis DNA can be demonstrated in lesional skin by PCR.545. and 549. Non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria have also been implicated.550. and 551.

Erythema induratum–nodular vasculitis is a lobular panniculitis. It is not possible to diagnose which cases are due to tuberculosis on the histology alone (see p. 463). Traditionally, erythema induratum has been distinguished from nodular vasculitis on the basis of more prominent necrosis of the fat lobules and the extension of tuberculoid granulomas into the lower dermis.

Lichen scrofulosorum is characterized by non-caseating tuberculoid granulomas in the upper dermis; 555 the lesions have a perifollicular and eccrine localization. 523 Bacilli are not demonstrable.

Papulonecrotic tuberculid exhibits ulceration and V-shaped areas of necrosis, which include a variable thickness of dermis and the overlying epidermis. There is a surrounding palisade of histiocytes and chronic inflammatory cells, and an occasional well-formed granuloma.536. and 545. Vessels in the vicinity show disruption and fibrinoid necrosis of their walls, sometimes with accompanying thrombosis or vasculitis.340. and 556. Follicular necrosis or suppuration is present in approximately 20% of cases. 537 No bacilli can be demonstrated using routine staining methods. 536

In nodular tuberculid granulomatous inflammation is located at the junction of the subcutaneous fat and the lower dermis. It involves the walls of arterioles. 552

The treatment of cutaneous tuberculosis usually involves the concurrent use of four drugs – isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and either ethambutol or streptomycin – for a period of 8 weeks.352.421. and 483. This quadruple therapy is followed by a 16-week course of isoniazid and rifampicin. Variations in these schedules have been used successfully.456.464. and 473. Pyridoxine may be added to this protocol to prevent the neurotoxicity of isoniazid. 405 Drug-resistant strains are becoming more frequent. Drug-resistant tuberculosis is defined as disease resistant to the first-line drugs rifampicin and isoniazid, ± resistance to other drugs. 557 In India, organism resistance to isoniazid varies from 13 to 45%, and for streptomycin it is 3–12%. 557 In such cases, the treatment can be changed to ethambutol, ofloxacin, and thioacetazone. 557

Because there is sometimes difficulty in making and/or confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis, a therapeutic trial of antituberculous therapy is sometimes commenced. It is generally thought that 6 weeks of therapy with three or four antituberculous drugs is adequate to prove or disprove the diagnosis. 558

The non-tuberculous (atypical, environmental) mycobacteria are a heterogeneous group of acid-fast bacteria which differ from M. tuberculosis in their clinical and cultural characteristics, as well as in their sensitivities to the various antimycobacterial drugs.559. and 560. The traditional Runyon classification of the non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria, which is based on colonial pigmentation, morphology, and growth characteristics, is of no relevance to dermatopathology.

Familial atypical mycobacteriosis (OMIM 209950) is a rare syndrome due to a constellation of genetic abnormalities, some of which have involved only a few families. The genes involved include the interferon-gamma receptor-1 and -2 genes (IFNGR1 and IFNGR2, respectively), the beta-1 chain of the interleukin-12 receptor (IL12RBI) gene, and the STAT-1 gene. 561

Non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria can cause infections in the lungs, lymph nodes, meninges, synovium, and skin.559.562. and 563. Cervicofacial lymphadenitis due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria is not uncommon in children. 564 Two species, M. ulcerans and M. marinum, result in well-defined clinicopathological entities known respectively as Buruli ulcer and swimming pool (fish tank) granuloma. They merit individual consideration. Cutaneous infections are rarely produced by the other non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria; when they occur they are associated with a diversity of clinical and histopathological appearances that are not species specific.330. and 565. Accordingly, they will be considered together after discussion of M. ulcerans and M. marinum infections.

Infections with Mycobacterium ulcerans (Buruli ulcer, Bairnsdale ulcer) have been reported from many areas of Central and West Africa,566. and 567. as well as from New Guinea, Australia, 568 southeast Asia, 569 and Mexico. The natural reservoir of the organism and the mode of transmission are unknown, 570 although current evidence suggests that infection is acquired through abraded skin after contact with contaminated water, soil, or vegetation.567. and 571. The organism has been identified by PCR in several cases of sea-urchin granulomas. 572 The organism grows preferentially at 32–33°C and produces an exotoxin which is responsible for tissue necrosis. 570 PCR testing can be used in tracing the source of the infection by means of a DNA fingerprinting method. 573

M. ulcerans produces lesions that predominantly involve the skin and subcutaneous fat, and less commonly the underlying fascia, muscle and, rarely, bone. Systemic spread is exceedingly rare. 574 The initial lesion is usually a papule or pustule on the extremities, particularly on the lower part of the legs. Ulceration soon develops and may extend quite rapidly. The ulcer is painless and has a characteristic undermined edge. 575 Satellite lesions may develop. 570 Affected individuals are usually children or young adults. 567 Patients with HIV infection may have aggressive infection. 576 Delay in presentation and time to diagnosis is often prolonged in non-endemic areas. 577

A consensus conference held in 2006 recommended surgical excision with a small rim of normal tissue as the treatment of choice. 578 Antibiotics play a role in countries in which surgery is not readily available, and in extensive disease. The WHO recommends the combination of oral rifampin (rifampicin) and parenteral streptomycin for initial treatment. Clarithromycin or ciprofloxacin may be added. 578 Treatment failure is less common if antibiotics are combined with surgery. 579

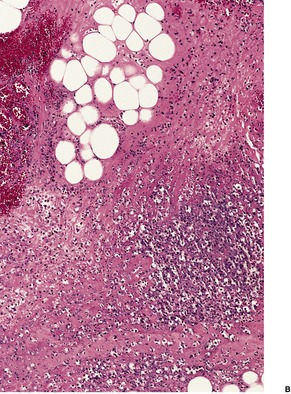

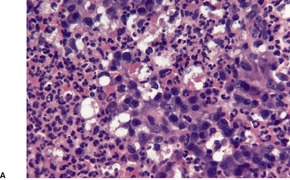

The most striking feature is extensive ‘coagulative’ necrosis involving the dermis and subcutaneous fat, with remarkably little cellular infiltration (Fig. 23.8). The necrosis is probably caused by a macrolide toxin called mycolactone. 581 A septolobular panniculitis is present in some areas. In the viable margins there is a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate. The epidermis at the margins of the ulceration shows variable changes; pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may sometimes be present. 582 There is sometimes a vasculitis involving small vessels in the septa of the subcutaneous fat adjacent to areas of fat necrosis. There are usually numerous clumps of acid-fast bacilli, sometimes forming globular structures, in the necrotic tissue. These organisms are extracellular in location.

Mycobacterium ulcerans. (A) There is necrosis of the dermis with peripheral extension beyond the limits of the surface ulceration (so-called ‘undermining’). An epidermal downgrowth is present at the edge of the ulcer. (B) There is suppuration and necrosis in the subcutis. (H & E)