PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ The history should focus on the patient’s melanoma history, including the histology of the primary tumor, disease-free interval between the primary diagnosis and the diagnosis of regional metastases, and the extent of both locoregional and distant disease. The history should also focus on comorbidities, past medical history, and medications that might impact the patient’s surgical candidacy.

■ The history should also include a thorough review of systems, specifically looking for symptoms suggestive of distant disease. Patients with symptoms worrisome for stage IV disease should have body imaging before proceeding with surgery.

■ A complete physical examination should pay particular attention to signs of local, regional, and distant disease. The site of the primary tumor and the skin between it and the regional basin should be examined for signs of in-transit recurrences. A complete lymph node exam should be performed. This should not just be limited to the axilla of concern but bilateral cervical, supraclavicular, epitrochlear, axillary, and inguinal basins. Suspicious nodes outside of the draining basins may represent stage IV disease.

■ For the involved axilla, the exam should focus on the extent of disease, including the size of the involved nodes and fixation. The ipsilateral arm should be examined for lymphedema, weakness, or sensory deficit, as these may be indicative of involvement of the axillary vein or brachial plexus. You should also document any conditions affecting the shoulder or upper extremity, which limits range of motion.

■ For patients who had an SLN biopsy or excisional biopsy, it is important to document any sensory or motor deficits that may have occurred at the first surgery as well as any seroma, hematoma, or infection. It may also be helpful to note the orientation of the incision, as this may impact the orientation of the ALND incision.

■ It is important to review with patients the expected postoperative course including drain management and arm exercises, as well as short-term and long-term morbidity, including the risk, prevention, and management of lymphedema.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ For asymptomatic patients with micrometastatic disease identified on SLN biopsy, there are no imaging studies necessary before proceeding with ALND.3 For patients with thick, ulcerated tumors (American Joint Commission Center [AJCC] stage T4b) and a positive SLN, the risk of distant disease may justify preoperative body imaging, with either a computed tomography (CT) scan or positron emission tomography (PET)/CT.4 However, for patients with micrometastatic disease, preoperative staging studies have a high false-positive rate, may lead to unnecessary follow-up studies or biopsies, and rarely alter surgical decision making.

■ Patients with symptoms concerning for metastatic disease should undergo staging with either a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or a PET/CT and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. Patients with clinically evident regional disease should also undergo distant staging, as there is a higher chance of detecting metastatic disease that might alter surgical decision making.3

■ For patients with fixed, matted lymph nodes; skin involvement; or neurovascular symptoms of the involved arm (paresthesias, motor and sensory deficits, lymphedema, limited range of motion), MRI of the chest wall can be helpful in determining resectability. Unresectable or borderline resectable patients could be considered for neoadjuvant therapy with newer biologic and targeted therapies.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ In the preoperative area, the side of the ALND should be clearly marked and confirmed with the patient before proceeding to the operating room (OR).

■ Intravenous (IV) antibiotics are indicated for ALND.5 Sequential compression devices (SCDs) should be used for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis. Patients with a history of DVT or genetic predisposition toward clotting should receive subcutaneous heparin.

■ Many surgeons prefer the use of short-acting neuromuscular blocking agents during induction, so that the patients are not paralyzed during the procedure. This allows identification of the thoracodorsal, long thoracic, and medial and lateral pectoral nerves by mechanical stimulation. However, this is not essential and some surgeons prefer paralysis with a long-acting neuromuscular blocking agent to prevent muscular contraction and allow for retraction of the pectoralis major and minor muscles. Either way, this should be discussed with the anesthesiologist prior to the case.

Positioning

■ The patient should be positioned supine on the OR table, toward the edge of the side of the ALND so that the posterior axillary line is in-line with the edge of the table. The ipsilateral arm is abducted at 90 degrees on a padded arm board. It is important not to extend the arm past 90 degrees to avoid brachial plexus injury.

■ The endotracheal tube should be located away from the involved arm and adequate space should be preserved above the arm for the surgical assistant.

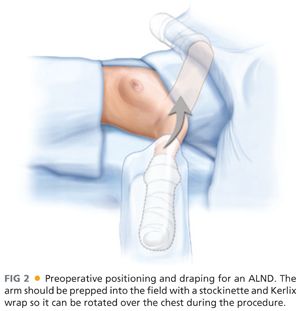

■ The chest wall, lower neck, and entire arm should be prepped and draped into the surgical field using a sterile stockinette and Kerlix wrap. This allows the arm to be rotated over the chest, relaxing the pectoralis major and minor (FIG 2).

TECHNIQUES

INCISION

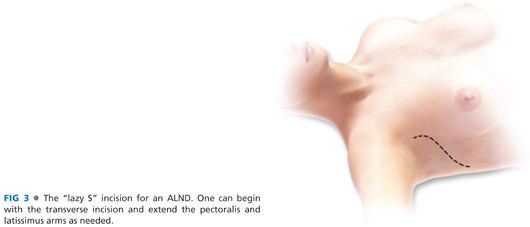

■ Typically, a “lazy S” incision is used along the pectoralis major muscle, extending posteriorly at the level of the axillary hair line, and then inferiorly along the latissimus dorsi muscle (FIG 3). For patients with a prior excisional or SLN biopsy incision, this should be encompassed into the ALND incision, and thus might impact the choice of incision. For patients with bulky adenopathy, particularly those with nodes close to the skin, the skin overlying the nodes should be included with the specimen. Be sure there is adequate skin to allow for a tension-free closure.

■ After incising the skin with a scalpel, electrocautery is used to divide the subcutaneous tissue and elevate skin flaps. Unless mandated by the presence of bulky disease, the skin flaps should not be too thin and get progressively thicker as they are raised. Thin skin flaps will increase the risk of wound complications and give the axilla a sunken-in appearance.

■ The skin is elevated using skin hooks or sharp rakes. It is important that the surgical assistant holds the flaps straight up and not retract them back (which residents will sometimes do in order to get a better view). The surgeon retracts the tissue with the opposite hand in order to apply strong countertraction and identify the appropriate tissue plane.

■ Surgeons are often hesitant to go too far or too deep while elevating the inferior skin flap at this initial point of the operation for fear of injuring the long thoracic nerve. However, raising an adequate inferior flap allows for greater mobility of the specimen and easier dissection. The inferior flap should be raised to approximately the level of the 5th rib.

■ Once the flaps are elevated, the next step will be to identify some of the borders of the axilla: the pectoralis major and minor muscles, the latissimus dorsi muscle, and the axillary vein. Although individual surgeons have their preferences, there is no correct order, and the presence of large lymph nodes might mandate changing your approach. In this chapter, we will describe a medial-to-lateral approach.

IDENTIFICATION AND RETRACTION OF THE PECTORALIS MAJOR AND MINOR

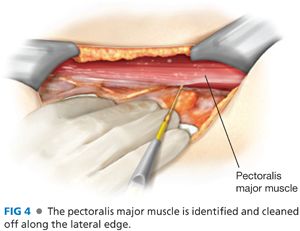

■ The pectoralis major muscle is usually the easiest margin to begin with, as it is often easily palpable upon raising the flaps (and may become apparent while elevating the superior flap). Once the pectoralis major is identified, the length of the lateral border should be exposed (FIG 4).

■ Once the pectoralis major muscle is freed, it is retracted anteriorly and medially to expose the interpectoral nodes and the pectoralis minor muscle. This, and the remainder of the operation, is facilitated by the use of a Thompson retractor (FIG 5).

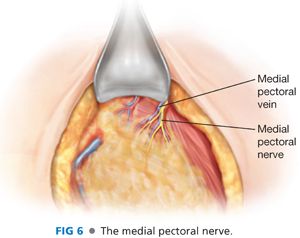

■ The tissue between the pectoralis major and minor muscle that contains the interpectoral (Rotter’s) nodes is included with the specimen, dissecting it off the pectoralis minor muscle. As the dissection proceeds onto the pectoralis minor, the medial pectoral bundle can be observed coming either through or lateral to the pectoralis minor (FIG 6). This should be preserved. There is often an accompanying vein with a branch going into the specimen. This will need to be clipped, taking care not to clip the medial pectoral nerve.

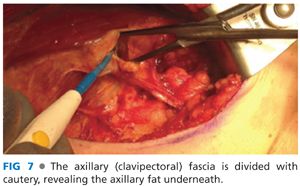

■ For patients undergoing an ALND for a positive SLN, the pectoralis minor can be preserved. The lateral edge of the pectoralis minor muscle is freed by dividing the axillary fascia (FIG 7). The axillary fascia is an extension of the clavipectoral fascia that divides the subcutaneous fat from the axillary fat. Upon dividing the fascia, you will notice the protrusion of a more yellow, globular fat. This is the lymph node–bearing tissue that needs to be excised.

■ The axillary contents are now swept laterally and the pectoralis minor muscle exposed along its length. Once this is done, the Thompson retractor can be repositioned so that both the pectoralis major and minor can be retracted anteriorly.

■ If there is bulky adenopathy and exposure of the upper axillary lymph nodes is difficult, it may be necessary to divide the pectoralis minor muscle, and this is described subsequently.

IDENTIFICATION OF THE AXILLARY VEIN

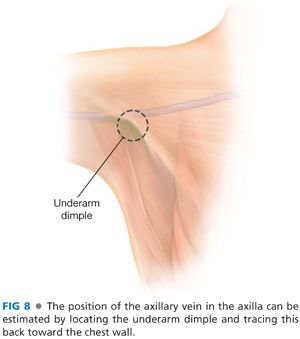

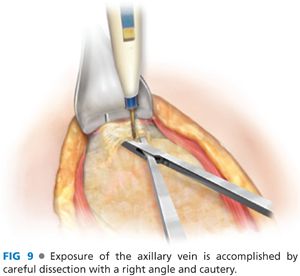

■ The vein often becomes visible medially during the elevation of the pectoralis musculature. If not, its general location can be anticipated by identifying the underarm dimple at the inferior aspect of the upper arm and tracing it toward the chest wall (FIG 8). Dissection down to the vein should not be performed directly with cautery to avoid an inadvertent injury, but rather, a careful dissection is recommended (FIG 9). Small venous branches and lymphatics should be clipped or suture ligated. It is also important not to find yourself superior to the vein, as the axillary artery and brachial plexus can be injured. Once the vein has been identified, the inferior margin should be cleared. It is not necessary to skeletonize the vein.

THE LATISSIMUS DORSI MUSCLE

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree