FIGURE 8-1 Contact dermatitis Characteristics of contact dermatitis seen on the lower extremity are a well-defined border of exposure, erythema, rash (at the proximal aspect of the wound), and patient complaint of itching under the bandages. Some of the dressing components that can cause an allergic reaction are sulfa, silver, silicone, iodine, or latex. Careful subjective history about possible allergies is important to minimize the risk of reactions that may inhibit wound healing or even extend the wound.

FIGURE 8-2 Contact dermatitis This patient with a known latex allergy was being treated for a chronic venous wound using antimicrobial dressings and multilayered compression bandages. After progressing well for several months, the wound and periwound tissue began to deteriorate with numerous areas of partial thickness skin loss like the one proximal to the primary wound. Cessation of any dressings that contained silver resulted in an immediate reversal of the symptoms, confirming a suspicion that she had a silver allergy. Infection and an allergic reaction can both cause deterioration of the wound bed, and are obviously treated quite differently. Confirmation of infection is by culture and allergy by removing the suspected offending agent.

The irritant type of contact dermatitis is not an immunological response, but a reaction to a caustic substance and depends on the concentration of the substance, for example, a chemical or topical liquid.

Patients with chronic leg wounds have an increased susceptibility to allergic contact dermatitis,4 especially if they are being treated with compression therapy. This condition is sometimes referred to as stasis dermatitis. If contact dermatitis is suspected or if the patient reports a history of allergies to other substances, patch testing can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. TABLE 8-3 provides a list of common allergens for patients who have wounds.

TABLE 8-3 Common Allergens for Contact Dermatitis

Clinical Presentation Signs of dermatitis include erythema, weeping, scaling of the periwound area, and itching. It can occur at any age; however, in the older population it can easily be misdiagnosed. In severe cases, shiny skin and alopecia may develop. A visible determining factor is that the symptoms occur only in areas of direct contact with the irritating material.

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis

Cellulitis

Vasculitis

Vasculitis

Medical Management The most important component of treating any dermatitis is the identification and discontinuation of the medication, dressing, or other substance that might be responsible for contact dermatitis. Low-dose topical steroids may help decrease inflammation and discomfort; systemic steroids may be beneficial if there is an extensive area of contact dermatitis.

Wound Management Patients usually require only supportive care and discontinuation of the irritating topical agent and, in the case of an existing wound, substitution of a dressing that has fewer or no allergens. Nonadherent hypoallergenic dressings are recommended for care of open lesions. Most products that are used for wound care are available in latex-free forms, as both patients and clinicians can suffer from latex allergies. The skin will usually heal in 2 to 3 weeks.

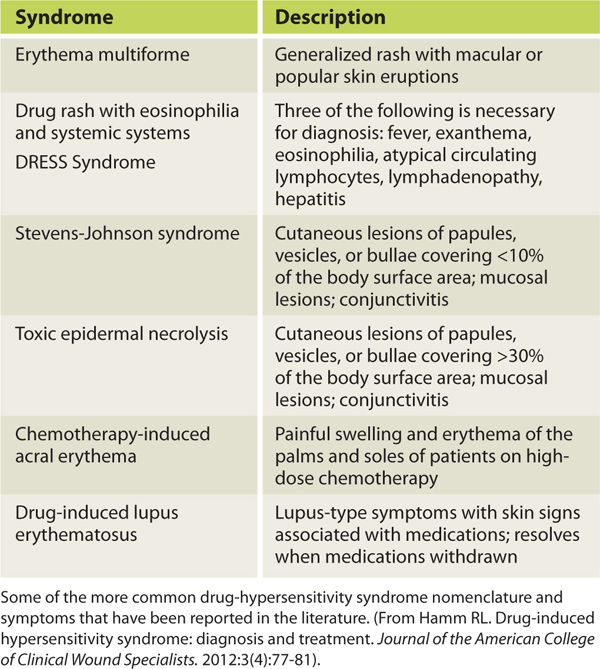

Drug-Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome

Pathophysiology Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) is an immunologic response to a drug received either orally, by injection, or by IV. Although not fully understood, the process is similar to what occurs with skin allergies except that the immune response is activated by the causative agents and their metabolites rather than by a direct effect on the keratinocytes.5 There are numerous syndromes based on severity, types of lesions and underlying diseases processes; however, all of them produce generalized (rather than localized) skin lesions and systemic symptoms (TABLE 8-4).

TABLE 8-4 Drug-Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome

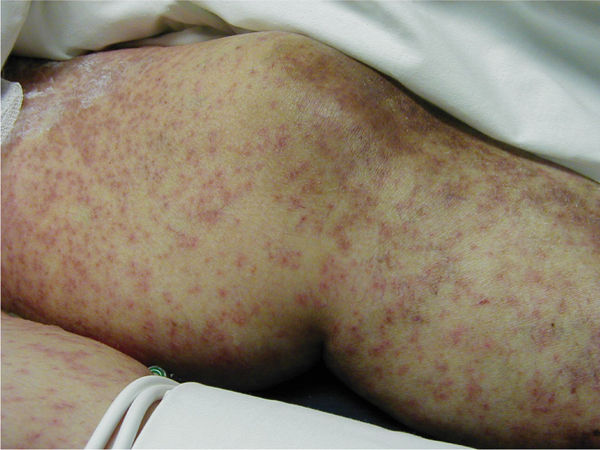

Clinical Presentation Symptoms include generalized rash (with or without vesicles) and any of the following: local eruptions, fever, lymphedema, mucosal lesions, conjunctivitis, and epidermal sloughing (FIGURE 8-3). Onset is usually 1 to 3 weeks after the first exposure to the offending drug, beginning with a fever or sore throat and progressing to the cutaneous/mucosal involvement. In the younger adult population (20 to 40 years), the syndrome is termed erythema multiforme.

FIGURE 8-3 Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome Diffuse generalized rash (with or without vesicles)—with symptoms of local eruptions, fever, lymphedema, mucosal lesions, conjunctivitis, and epidermal sloughing—can occur on any part of the body as a result of an allergic or hypersensitive reaction to medications. Unlike a local allergic response, DIHS involves a larger surface area without direct exposure to a specific substance.

Differential Diagnosis

Infection

Infection

Vasculitis

Vasculitis

Contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis

Medical Management Medical management begins with identification and cessation of the causative agent, which is usually the last one that the patient has initiated taking. Depending on the severity of the symptoms, corticosteroids are used to prevent progression and relieve symptoms, and supportive care is provided in an intensive care unit or a burn unit for more severe cases.

Wound Management In minor cases, cessation of the medication may be sufficient to reverse symptoms and no wound care is needed. In more severe cases with epidermal sloughing, treatment is similar to that of a deep superficial burn except that debridement of the detached epidermal tissue is usually not advisable. Nonadherent antimicrobial dressings are recommended to help prevent infection and to avoid further skin tearing with dressing changes. Prevention of fluid loss and infection is paramount, and as the patient improves, dressings to promote reepithelialization are advised.

Autoimmune Disorders

Vasculitis Vasculitis is an inflammatory disorder of blood vessels, which can ultimately result in organ damage, including the skin. The etiology is often idiopathic—it is a reaction pattern that may be triggered by certain comorbidities including underlying infection, malignancy, medication, and connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythamatosus (FIGURE 8-4). Circulating immune complexes (antibody/antigen) deposit in the blood vessel walls, causing inflammation that may be segmental or involve the entire vessel. At the site of inflammation, varying degrees of cellular inflammation and resulting necrosis or scarring occur in one or more layers of the vessel wall, and inflammation in the media of the muscular artery tends to destroy the internal elastic lamina. 6–7

FIGURE 8-4 Vasculitis due to SLE Vasculitis presents as dermal necrosis as a result of occluded small arteriole and is exquisitely painful, making local care very difficult. Patients with autoimmune disorders, for example, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are at greater risk. The medications used to treat SLE further complicate and inhibit wound healing.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a histopathologic term used to describe findings in small-vessel vasculitis, refers to the breakdown of inflammatory cells that leaves small nuclear fragments in and around the vessels. Vasculitic inflammation tends to be transmural, rarely necrotizing, and nongranulomatous. Resolution of the inflammation tends to result in fibrosis and intimal hypertrophy, which in combination with secondary clot formation, can narrow the arterial lumen and account for the tissue ischemia or necrosis.8 Clinical symptoms (ie, tissue loss) depend on the artery or arteries that are involved and the extent of lumen occlusion. Cutaneous vasculitis usually occurs in the lower extremities and feet.

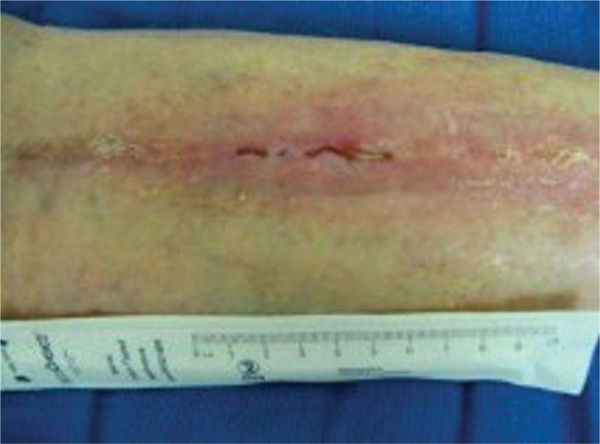

Clinical Presentation Clinical presentation, which varies depending on the arterial involvement, includes palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, pain, skin lesions with or without nodules, and tissue necrosis. It may present as one large necrotic lesion or several small lesions, but all are full thickness after debridement. Systemic systems may also be present and usually relate to kidney, lung, or gastrointestinal tract involvement. On some occasions, signs of vasculitis in other organs may appear at the same time that skin lesions appear (FIGURES 8-5, 8-6). One very distinctive characteristic for differential diagnosis from chronic venous wounds is the exquisite pain that occurs with vasculitis, making the initial local treatment very tedious.

FIGURE 8-5 Vasculitis associated with other symptoms This patient with vasculitis of the posterior calf noted the onset of pain and dermal symptoms at the same time that he experienced neurological signs associated with what was diagnosed as a CVA. Both maladies occurred after the stress of losing a family member. Note the discoloration of the proximal periwound skin, indicating that the inflammation is still evolving.

FIGURE 8-6 Vasculitis in the remodeling phase of healing The patient in Figure 8-5 was treated with low-frequency noncontact ultrasound, nonadherent dressings to facilitate autolytic debridement, and compression therapy. He progressed to full closure of the wounds without surgical intervention. Topical 2% Lidocaine gel was applied prior to each treatment for assistance with pain management.

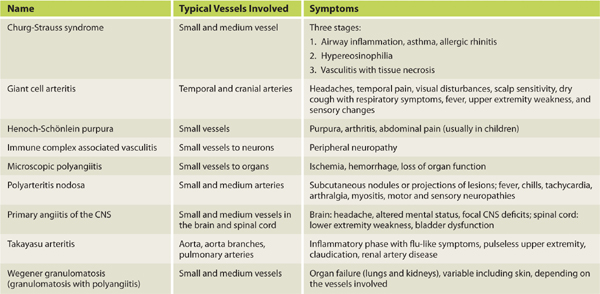

Differential Diagnosis (TABLE 8-5)

TABLE 8-5 Vasculitic Syndromes

Giant cell arteritis

Giant cell arteritis

Primary angiitis of the CNS

Primary angiitis of the CNS

Takayasu arteritis

Takayasu arteritis

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Immune complex–associated vasculitis

Immune complex–associated vasculitis

Microscopic polyangiitis

Microscopic polyangiitis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Wegener granulomatosis

Wegener granulomatosis

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Chronic venous wounds

Chronic venous wounds

Medical Management Treatment of any vasculitis depends on the etiology, extent, and severity of the disease. For secondary vasculitic disorders, treating the underlying comorbidity (eg, infection, drug use, cancer, or autoimmune disorder) is crucial.

Remission of life- or organ-threatening disorders is induced by using cytotoxic immunosuppressants (eg, cyclophosphamide) and high-dose corticosteroids, usually for 3 to 6 months, until remission occurs or until the disease activity is acceptably reduced. Adjusting treatment to maintain remission takes longer, usually 1 to 2 years. During this period, the goal is to eliminate corticosteroids, reduce the dosage, or use less potent immunosuppressants as long as needed. After tapering or eliminating corticosteroids, methotrexate or azathioprine can be substituted to maintain remission.

Wound Management Initial treatment of wounds caused by vasculitis is extremely difficult because of the pain. The principles of standard wound care (debride necrotic tissue, treat inflammation and infection, apply moist wound dressings, nurture the edges, and ensure optimal oxygen supply, termed TIMEO2)9 are recommended. Topical lidocaine helps reduce pain during treatments, noncontact low-frequency ultrasound helps mobilize cellular activity and interstitial fluids, and compression therapy helps manage the edema that occurs in the lower extremities as a result of the inflammation and decreased mobility. Nonadherent dressings that promote autolysis of the necrotic tissue (eg, X-Cell, Medline, Mundelein, IL) are excellent initially, especially in reducing pain levels with dressing changes. Silicone-backed foam dressings are helpful in absorbing exudate as well as in reducing pain. If the patient is on steroids, local vitamin A can be used to negate the effects of steroids. As the acute inflammation recedes, pain levels decrease, and wound healing progresses to proliferation, treatment can be more aggressive.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Pathophysiology The antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by elevated titres of different antiphospholipid antibodies. It consists of arteriole thrombosis (and in pregnancy, fetal demise) associated with various autoimmune antibodies directed against one or more phospholipid-binding proteins (eg, anti-β2-glycoprotein I, anticardiolipin, and lupus anticoagulant).10 These proteins normally bind to phospholipid membrane constituents and protect them from excessive coagulation activation. The autoantibodies displace the protective proteins and thus produce procoagulant endothelial cell surfaces and cause arterial or venous thrombosis. In vitro clotting tests may paradoxically be prolonged because the antiprotein/phospholipid antibodies interfere with coagulation factor assembly and with activation on the phospholipid components that are added to plasma to initiate the tests.

The lupus anticoagulant is an antiphospholipid autoantibody that binds to protein-phospholipid complexes. It was initially recognized in patients with SLE; however, these patients now account for a minority of patients with the autoantibody. The lupus anticoagulant is suspected if the PTT is prolonged and does not correct immediately upon 1:1 mixing with normal plasma but does return to normal upon the addition of an excessive quantity of phospholipids (done by the hematology laboratory). Antiphospholipid antibodies in patient plasma are measured by immunoassays of IgG and IgM antibodies that bind to phospholipid-β2-glycoprotein I complexes on microtiter plates.10

Clinical Presentation The arteriole thrombosis results in venous swelling, creating the typical livedo reticularis skin appearance. In addition, the lower extremities may have superficial thrombophlebitis with cutaneous infarcts. As the disease progresses, skin necrosis may occur (FIGURE 8-7).

FIGURE 8-7 Antiphospholipid syndrome Antiphospholipid syndrome is characterized in the early stages by livedo reticularis (resulting in small brown spots on the skin) and in the later stages by ischemic skin changes. (Used with permission from Lichtman MA, Shafer JA, Felgar RE, Wang N. A External Manifestations. In: Lichtman MA, Shafer JA, Felgar RE, Wang N. eds. Lichtman’s Atlas of Hematology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=368&Sectionid=40094294. Accessed November 12, 2014.)

Differential Diagnosis

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Infective endocarditis

Infective endocarditis

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Medical Management Asymptomatic individuals in whom blood test findings are positive do not require specific treatment.

Prophylactic therapy involves elimination of other risk factors such as oral contraceptives, smoking, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia. For patients with SLE, hydroxychloroquine, an anti-inflammatory which may have intrinsic antithrombotic properties, may be useful. Statins are beneficial for patients with hyperlipidemia. If the patient has a thrombosis, full anticoagulation with intravenous or subcutaneous heparin followed by warfarin therapy is recommended.10,11,12

Based on the most recent evidence, a reasonable target for the international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 to 3.0 for venous thrombosis and 3.0 for arterial thrombosis. Patients with recurrent thrombotic events, while well maintained on the above regimens, may require an INR of 3.0 to 4.0. For severe or refractory cases, a combination of warfarin and aspirin may be used. Treatment for significant thrombotic events in patients with APS is generally lifelong.

Wound Management Conservative wound care is recommended for patients with skin lesions, keeping the wound moist and following wound bed preparation principles. Healing of wounds caused by other etiologies, eg. trauma or spider bites, will be delayed.

Pemphigus

Pathophysiology Pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease resulting from loss of normal intercellular attachments in the skin and oral mucosal membrane. Circulating antibodies attack the cell surface adhesion molecule desmoglein at the desmosomal cell junction in the suprabasal layer of the epidermis, resulting in the destruction of the adhesion molecules (acantholysis) and initiating an inflammatory response that causes blistering. There are three major forms of pemphigus: pemphigus foliaceus (FIGURE 8-8) and pemphigus vulgaris that have IgG autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3, respectively; and paraneoplastic pemphigus that has IgG autoantibodies against plakins and desmogleins (FIGURE 8-9).

FIGURE 8-8 Pemphigus Pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by blistering of the epidermis followed by crusting and sloughing, resulting in painful wounds and discoloration after healing. Complications include bacterial and viral infections as a result of the open wounds and immunosuppression, as well as sequelae from long-term use of corticosteroids (osteoporosis, avascular necrosis).

FIGURE 8-9 Paraneoplastic pemphigus Characteristics of paraneoplastic pemphigus include extensive lesions on the lips, severe stomatitis, and erythematous macules and papules that coalesce into large cutaneous lesions. The lesions are diagnosed by biopsy that shows a mix of individual cell necrosis, interface change, and acantholysis. (Used with permission from Anhalt GJ, Mimouni D. Chapter 55. Paraneoplastic Pemphigus. In: Wolff K, ed. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=56037677. Accessed August 24, 2013.)

Clinical Presentation Pemphigus vulgaris, the most common type, involves the mucosa and skin, especially of the scalp, face, axilla, groins, trunk, and points of pressure. Patients usually present with painful oral mucosal erosions and flaccid blisters, erosions, crusts, and macular erythema in areas of skin involvement.10,12 The primary cell adhesion loss is at the deeper suprabasal layer. (Refer to Chapter 1 for a review of the skin anatomy.) Pemphigus foliaceus is a milder form of the disease, with the acantholysis occurring more superficial in the epidermis and usually on the face and chest. Paraneoplastic pemphigus, in addition to having different autoantibodies, occurs exclusively on patients who have some type of malignancy, usually a lymphoproliferative disorder (FIGURE 8-9). Because of the malignancy, mortality is high in this type of pemphigus.13

Differential Diagnosis Diagnosis is confirmed by using immunofluorescence to demonstrate the IgG autoantibodies against the cell surface of intraepidermal keratinocytes.

Medical Management Medical treatment of all three types consists of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy.

Wound Management Wound management is conservative with the goal of preventing infection and promoting reepithelialization if denuding occurs with the blistering. Flat antimicrobial dressings (eg, Acticoat Flex, Smith & Nephew, Largo, FL) are useful over open areas, and hydrotherapy is beneficial when the disease is widespread and in the crusty phase. Secondary dressings are required for most areas, and can include surgical or fish-net garments. Silicone-backed foam dressings without adhesive borders are also recommended for easy removal of loose necrotic tissue without causing painful skin tears.

Bullous Pemphigoid

Pathophysiology Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is associated with tissue-bound and circulating autoantibodies directed against BP antigen 180 and BP antigen 230, both components of the basement membrane.12 An immune reaction is initiated by the formation of IgG autoantibodies that target dystonin, a component of the hemidesmosomes, resulting in the infiltration of immune cells to the area. The consequence is separation of the dermal/epidermal junction with fluid collection and blistering or bullae.

Clinical Presentation BP occurs most commonly among the elderly, and the most common sites of involvement include inner aspects of thighs, flexor aspects of forearms, axilla, groin, and oral cavity. The extremities can also become involved. Clinically, patients can present with urticarial plaques with intense pruritis to widespread tense bulla filled with clear fluid (FIGURE 8-10).

FIGURE 8-10 Bullous pemphigoid Tense bullae filled with clear fluid (a result of the inflammatory process) are typical of bullous pemphigoid.

Differential Diagnosis Histologically, BP is the prototype of a subepidermal bullous disease along with eosinophilic spongiosis. The dermis shows an inflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the dermal-epidermal junction on direct immuno-flouroscence.10,12

Medical Management Medical options include systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy.

Wound Management Wound management recommendations are the same as for pemphigus, with the goal of minimizing pain, preventing infection, and promoting reepithelialization.

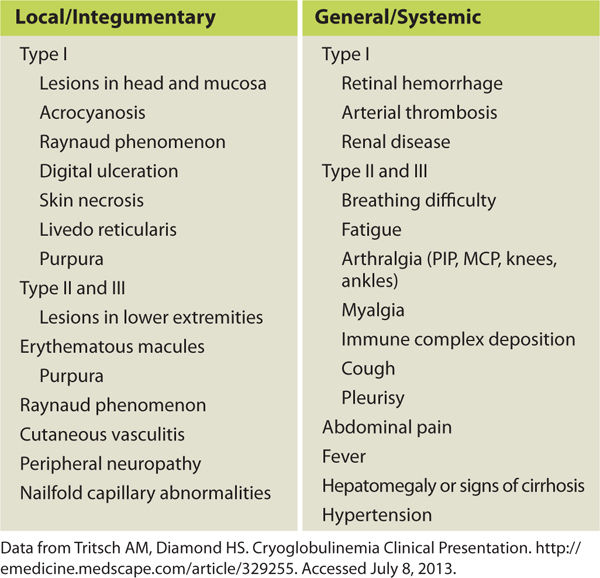

Cryoglobulinemia

Pathophysiology Cryoglobulins are abnormal proteins (immunoglobulins), and cryoglobulinemia is the presence of these proteins in the blood. They coagulate or become thick and gel-like in temperatures below body temperature (37° C), thereby clogging the small blood vessels and causing hypoxic skin changes, ischemic wounds, or other organ damage (TABLE 8-6). The symptoms are reversible if the environmental temperature is warmed. The disorder is grouped into three main types, depending on the type of antibody that is produced: Type I is most often related to cancer of the blood or immune system, for example, multiple myeloma. Types II and III, also referred to as mixed cryoglobulinemia, most often occur in people who have a chronic inflammatory condition, for example, hepatitis C or systemic lupus erythematosus. Type II is the most common type, and most of these patients also have hepatitis C.1,10,12

TABLE 8-6 Symptoms of Cryoglobulinemia

Clinical Presentation Symptoms vary depending on the type of cryoglobulinemia present and the organs that are affected. Systemic signs may include difficulty breathing, fatigue, glomerulonephritis, joint pain, and muscle pain. Integumentary signs may begin with purpura and Raynaud phenomenon (FIGURE 8-11). Meltzer triad, associated with Types II and III, includes arthralgia, purpura, and weakness.14 See TABLE 8-6 for a list of cryoglobulinemia symptoms.

FIGURE 8-11 Cryoglobulinemia Cryoglobulinemia on the foot of a patient with hepatitis C. Classic signs include purpura, loss of dermis due to occlusion of the small vessels to the skin, severe pain, and tendency to develop infections. This patient’s wounds healed with the use of antibiotics and standard wound care; however, when he returned to a cold climate his symptoms recurred.

Differential Diagnosis

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis

Giant cell arteritis

Giant cell arteritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Medical Management Treatment of mild or moderate cryoglobulinemia depends on the underlying cause, and treating the cause will often treat the cryoglobulinemia as well. Mild cases can be treated simply by avoiding cold temperatures. Standard hepatitis C treatments usually work for patients who have hepatitis C and mild or moderate cryoglobulinemia. However, the condition can return when treatment stops. NSAIDs may be used to treat mild cases that involve arthralgia and myalgia. Severe cryoglobulinemia (involving vital organs or large areas of skin) is treated with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, interferon, or cytotoxic medications. Plasmapheresis may be indicated if the complications are life threatening.15

Wound Management Wound care involves treatment of infection and pain management, especially in the early stages. Nonadherent dressings such as X-Cell (Medline, Mundelein, IL), hydrogel, Acticoat (Smith & Nephew, Largo, FL), and petrolatum gauze help minimize pain with dressing changes and promote autolytic debridement. A topical anesthetic is advised 10 to 15 minutes before initiating any sharp debridement; enzymatic debridement may also be beneficial but can cause stinging and burning upon application. Absorbent dressings are advised if there is wound drainage, and modified compression (eg, with short stretch bandages) helps reduce edema that occurs with chronic inflammation, immobility, and lower extremity dependency. Compression bandages also help keep the extremities warm and facilitate vasodilation. If edema is not severe, warm hydrotherapy can help reduce precipitation of the cryoglobulins and relieve ischemic pain. Patient education regarding avoidance of cold or wearing warm clothing such as thermal socks is a crucial component of long-term management.

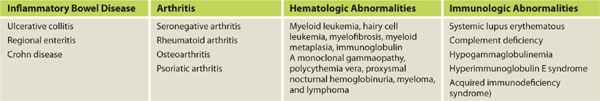

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Pathophysiology Pyoderma gangrenosum (PD) is an autoimmune disorder of unknown etiology that leads to painful skin necrosis. PD is commonly associated with other inflammatory diseases such as Crohn disease, inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, and hematologic malignancy.15 Pathergy, the development of skin lesions in the area of trauma or the enlargement of initially small lesions, is commonly seen with PD, especially if debridement of necrotic tissue is attempted. Neutrophilic dermatosis occurs with altered neutrophilic chemotaxis and is thought to be part of the pathology.16

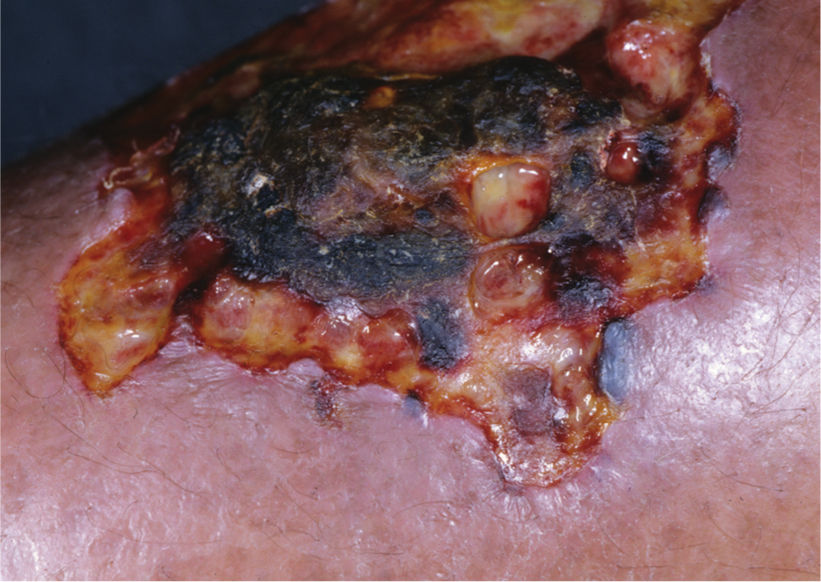

Clinical Presentation PD ulcers usually begin as small pustules or blisters and become larger with a violaceous border and surrounding erythema. The first lesion may be at the site of minor trauma, but will progress and enlarge rapidly. They are painful, necrotic, and usually recurring. Sometimes PD will appear in groups of lesions at different stages of formation or healing. They do not respond to standard care if diagnosed as another wound type, and indeed may worsen if the standard TIMEO2 care is administered (FIGURES 8-12 to 8-14).

FIGURE 8-12 Pyoderma gangrenosum Pyoderma gangrenosum on the abdomen of a female with diabetes. The PD developed after an open hysterectomy. The wounds were treated with nonadherent antimicrobial dressings (X-cell) in order to minimize pain, facilitate autolytic debridement and re-epithelialization, and prevent infection. As the necrotic plaques loosened and new skin was visible beneath, they were removed with sterile forceps; however, aggressive debridement is contraindicated.

FIGURE 8-13 Pyoderma gangrenosum Some of the symptoms of PD are seen on this lower extremity wound, including the violaceous border, purulence, and necrotic tissue. (Used with permission from Flowers D, Usatine RP. Chapter 167. Pyoderma Gangrenosum. In: Usatine RP, Smith MA, Chumley H, Mayeaux, Jr. E, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=8208222. Accessed August 24, 2013.)

FIGURE 8-14 Pyoderma gangrenosum The clinical appearance of PD can vary, as in this wound with both eschar and purulent subcutaneous tissue at the edges. (Used with permission from Flowers D, Usatine RP. Chapter 167. Pyoderma Gangrenosum. In: Usatine RP, Smith MA, Chumley H, Mayeaux, Jr. E, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=8208222. Accessed August 24, 2013.)

Differential Diagnosis As there is no diagnostic test to confirm PD and multiple other conditions that resemble PD, a correct diagnosis relies on clinical presentation and exclusion of other causes. TABLE 8-7 lists the systemic diseases most often associated with PD. Further differentiation is made into these four subgroups: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative.12,17

TABLE 8-7 Systemic Diseases Associated with Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Medical Management18 Systemic management includes treatment of any underlying disease; systemic steroids are recommended for severe or widespread disease. Other therapies that have been used in patients with PD include antibiotics (dapsone and minocycline), cyclosporine, clofazimine, azathioprine, methotrexate, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, tacrolimus, mycophenolate, mofetil, IV immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, and infliximab.10,12,19

Wound Management Topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, nicotine patches, and intralesional steroids have been used for mild or moderate disease. Debridement of adhered tissue is contraindicated and may cause pathergy; however, as the necrotic tissue loosens with reepithelialization, it may be gently removed with sterile forceps. Keeping the lesions covered with a nonadherent mesh or silicone-backed wicking foam that will allow drainage to escape to a secondary dressing can help alleviate the pain associated with PD wound care. Split-thickness skin grafts, along with concurrent immunosuppressive therapy to reduce the risk of pathergy, have been reported.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica Diabeticorum

Pathophysiology Necrobiosis Lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a disease of unknown etiology that is usually seen in morbidly obese patients with a strong family history of diabetes. Different pathological mechanisms have been proposed and include microangiopathic and neuropathic processes, abnormal collagen degeneration, abnormal immune mechanisms, and abnormal leukocyte function. NLD also results in thickening of the blood vessel walls and fat deposition, making the integumentary symptoms similar to vasculitis. The disease tends to be chronic with recurrent lesions and scarring.19

Clinical Presentation Lesions usually are bilateral but asymmetric on the tibial surface of the lower leg, and begin as a rash or 1 to 3 mm slightly raised spots. They progress to irregular ovoid reddish-brown plaques with shiny yellow centers and violaceous indurated borders. The edges may be raised and purple, and the wound bed may have good granulation tissue but no epithelial migration. Pain and edema are also usually present. Remodeling is characterized by round patches of hyperpigmentation (FIGURE 8-15).10,12,20

FIGURE 8-15 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum NLD lesions are characterized by symmetrical tan-pink or yellow plaques with well-demarcated, raised borders and depressed, atrophied centers. Telangiectasia is also visible throughout the wound. (Used with permission from Suurmond D. Section 15. Endocrine, Metabolic, Nutritional, and Genetic Diseases. In: Suurmond D, ed. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=5189157. Accessed August 24, 2013.)

Differential Diagnosis

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis

Vasculitis

Vasculitis

Diabetic wound with peripheral vascular disease

Diabetic wound with peripheral vascular disease

Medical Management Systemic steroids or other immunotherapy can be given in patients with severe disease. Blood thinners such as pentoxifylline and aspirin may be helpful in facilitating cell migration to the damaged tissue.

Wound Management Topical and intralesional steroids can be beneficial in treating mild to moderate cases. Other reported treatments include 0.1% topical tacrolimus ointment,20 collagen matrix dressings,21 and phototherapy.22 A combination of low-frequency noncontact ultrasound, topical steroid ointment, saline-impregnated cellulose dressings, and multilayer compression wraps, in conjunction with pentoxifylline, was a successful combination used by the editor for a patient with chronic lesions of more than 1 year duration.

Scleroderma

Pathophysiology Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) is a chronic disease that causes the skin to become thick and hard (sclerotic) with a buildup of scar tissue, resulting in loss of skin elasticity, joint range of motion, muscle strength, and mobility. Patients with scleroderma usually have proliferation of fibroblasts and excessive collagen proteins. There is also damage to internal organs such as the heart and blood vessels, lungs, stomach, kidneys, heart, and other organs. Scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder of unknown etiology that usually affects women between the age of 30 and 50 and results in extensive scarring and disfigurement as it progresses.23

The sequence of scleroderma involves the following: arteriole endothelial cells die by apoptosis and are replaced by collagen; inflammatory cells infiltrate the arteriole and cause more damage, resulting in the scarred fibrotic tissue that is the hallmark of scleroderma.10,12

Clinical Presentation The two main types of scleroderma are localized and systemic. Localized is further differentiated into morphea with discolored patches on the skin, and linear with streaks or bands of thick hard skin on the arms and legs. Localized scleroderma only affects the skin and not the internal organs. Systemic scleroderma can be limited (affecting only the arms, hands, and face) or diffuse (rapidly progressing, affecting large areas of the skin and one or more organs). Thirty-five percent of the patients with scleroderma develop skin ulcers that are painful, refractory, and over bony prominences (FIGURE 8-16). CREST, a limited systemic form of scleroderma, is described in TABLE 8-8. In addition, patients may experience joint pain, fatigue, depression, reduced libido, and altered body image. A third type is scleroderma sine sclerosis, which includes Raynaud phenomenon and internal involvement without sclerotic skin.24

FIGURE 8-16 Scleroderma Scleroderma causes the skin to lose its elasticity, resulting in loss of joint range of motion, strength, and function. The thick linear bands around the fingers are indicative of localized linear scleroderma.

TABLE 8-8 CREST is a Scleroderma Syndrome Characterized by the Following Symptoms:

Differential Diagnosis Other systemic autoimmune diseases, for example, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Medical Management Because the etiology is unknown, treatment of scleroderma centers on alleviating symptoms, preserving skin integrity with protective strategies, and preventing infection. D-penicillamine, colchicine, PUVA, relaxin, cyclosporine, and omega-oil derivatives have been used to treat the skin fibrosis. Immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine have been used to treat the systemic disease. Plasmapheresis can be used in severe cases. 1,16

Wound Management Local wound care is tedious because of the high-pain levels associated with open wounds on sclerotic skin, and wound healing is impeded by the scarring of the subcutaneous tissue and the immunosuppressive medications. Enzymatic debridement with collagenase may be helpful with painful wounds, as well as occlusive dressings to help with autolytic debridement. Nonadherent dressings are advised both to minimize pain and avoid tearing skin upon removal. Silicone-backed foam dressings are useful as secondary dressings. Patient education regarding protective measures for skin is crucial, for example, using gloves when doing housework, avoiding caustic liquids, wearing warm clothes to avoid Raynaud phenomenon, and using moisturizers to avoid dry skin. As the disease progresses, custom shoes with molded inserts to accommodate changes in the shape of the feet can help maintain independent ambulation.

Herpes Virus

Pathophysiology Varicella is a virus that presents in three different ways: herpes simplex Type 1 (oral or cold sores), herpes simplex Type 2 (genital herpes), and herpes zoster (varicella-zoster or shingles). Herpes simplex, commonly referred to as “cold sores,” is caused by recurrent infections with herpes simplex virus (HSV), a DNA virus that invades the cell nucleus and replicates, thereby producing partial thickness wounds on the mouth and lips (FIGURE 8-17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree