Allergic Contact Dermatitis: Introduction

|

As the largest organ in the human body, the skin is a complex and dynamic organ that serves among many other purposes, the function of maintaining a physical and immunologic barrier to the environment. Therefore, the skin is the first line of defense after exposure to a variety of chemicals. Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) accounts for at least 20% or more of the new incident cases in the subgroup of contact dermatitides (irritant contact dermatitis accounts for the remaining 80%).1 ACD, as the name implies, is an adverse cutaneous inflammatory reaction caused by contact with a specific exogenous allergen to which a person has developed allergic sensitization. More than 3,700 chemicals have been implicated as causal agents of ACD in humans.2 Following contact with an allergen, the skin reacts immunologically, giving the clinical expression of eczematous inflammation. In ACD the severity of the eczematous dermatitis can range from a mild, short-lived condition to a severe, persistent, chronic disease. Appropriate allergen identification through proper epicutaneous patch testing has been demonstrated to improve quality of life as measured by standard tools,3 as it allows for appropriate avoidance of the inciting allergen and possibly sustained remission of this potentially debilitating condition. Recognition of the presenting signs and symptoms, and appropriate patch testing are crucial in the evaluation of a patient with suspected ACD.

Epidemiology

A small but substantial number of studies have investigated the prevalence of contact allergy in the general population and in unselected subgroups of the general population. In 2007, Thyssen and colleagues4 performed a retrospective study that reviewed the main findings from previously published epidemiological studies on contact allergy in unselected populations including all age groups and most publishing countries (mainly North America and Western Europe). Based on these heterogeneous published data collected between 1966 and 2007, the median prevalence of contact allergy to at least one allergen in the general population was 21.2%. Additionally, the study found that the most prevalent contact allergens in the general population were nickel, thimerosal, and fragrance mix. Importantly, the prevalence of contact allergy to specific allergens differs between various countries5,6 and the prevalence to a specific allergen is not necessarily static, as it is influenced by changes and developments in the regional environment, exposure patterns, regulatory standards, and societal customs and values.

![]() Different frequency data for screening series allergens are seen when the subjects studied are part of a selected population referred for patch testing because of suspected ACD. There are numerous retrospective clinical and occupational studies from study centers and groups, for patch-test patients who already have dermatitis and are suspected to have ACD. In those cases, the prevalence of positive responses to contact allergens during patch testing varies with referral patterns, selection criteria for patch testing, regional variations in allergen exposure, and the allergens tested.7 This type of data is thus affected to a varying extent, by selection bias inherent in referral to a patch-test center and may not be representative of the general population. Such data nevertheless allows the recognition of chemicals with high allergenic potential depending on patient age and gender, specific body site of involvement, geographical location, etc., thus adding to our accumulated knowledge of contact dermatitis. Table 13-1 lists the most common allergens that elicited positive patch-test reactions in a group of patients who were tested by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) during 2007–2008.

Different frequency data for screening series allergens are seen when the subjects studied are part of a selected population referred for patch testing because of suspected ACD. There are numerous retrospective clinical and occupational studies from study centers and groups, for patch-test patients who already have dermatitis and are suspected to have ACD. In those cases, the prevalence of positive responses to contact allergens during patch testing varies with referral patterns, selection criteria for patch testing, regional variations in allergen exposure, and the allergens tested.7 This type of data is thus affected to a varying extent, by selection bias inherent in referral to a patch-test center and may not be representative of the general population. Such data nevertheless allows the recognition of chemicals with high allergenic potential depending on patient age and gender, specific body site of involvement, geographical location, etc., thus adding to our accumulated knowledge of contact dermatitis. Table 13-1 lists the most common allergens that elicited positive patch-test reactions in a group of patients who were tested by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) during 2007–2008.

Test Substance | % Positives | |

|---|---|---|

1. | Nickel sulfate (2.5%) | 19.5 |

2. | Myroxylon pereirae (25%) | 11.0 |

3. | Neomycin (20%) | 10.1 |

4. | Fragrance mix I (8%) | 9.4 |

5. | Quaternium 15 (2%) | 8.6 |

6. | Cobalt chloride (1%) | 8.2 |

7. | Bacitracin (20%) | 7.9 |

8. | Formaldehyde (1% aq.) | 7.7 |

9. | Methyldibromoglutaronitrile (2.0%) | 5.5 |

10. | p-Phenylenediamine (1%) | 5.3 |

11. | Propolis (10%) | 4.9 |

12. | Carba mix (3%) | 4.5 |

13. | Potassium dichromate (0.25%) | 4.1 |

14. | Fragrance mix II (14%) | 3.6 |

15. | Methylchloroisothiazolinone/Methylisothiazolinone (100 ppm aq.) | 3.6 |

16. | Thiuram mix (1%) | 3.4 |

17. | Bronopol (0.5%) | 3.1 |

18. | Diazolidininyl urea (1%) | 3.1 |

19. | Iodopropynyl butylcarbamate (0.5%) | 3.1 |

20. | Colophony (20%) | 2.8 |

21. | DMDM hydantoin (1%) | 2.7 |

22. | Tixocortol-21-pivalate (1%) | 2.5 |

23. | Cinnamic aldehyde (1%) | 2.4 |

24. | Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2%) | 2.4 |

25. | Imidazolidinyl urea (2%) | 2.4 |

26. | Lanolin alcohol (30%) | 2.1 |

27. | Propylene glycol (30% aq.) | 2.1 |

28. | Glyceryl thioglycolate (1%) | 1.8 |

29. | Diazolidinyl urea (1% aq.) | 1.7 |

30. | Bisphenol A epoxy resin (1%) | 1.7 |

31. | Amidoamine (0.1 aq.) | 1.6 |

32. | Ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (1%) | 1.5 |

33. | Imidazolidinyl urea (2% aq.) | 1.5 |

34. | Bisphenol F epoxy resin (0.25%) | 1.4 |

35. | Compositae mix (6%) | 1.4 |

36. | Tea tree oil, oxidized (5%) | 1.4 |

37. | Canaga odorata oil (Ylang ylang) (2%) | 1.4 |

38. | Benzocaine (5%) | 1.3 |

39. | Coconut diethanolamide (0.5%) | 1.2 |

40. | Ethyl acrylate (0.1%) | 1.2 |

41. | Methyl methacrylate (2%) | 1.2 |

42. | p-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin (1%) | 1.2 |

43. | Cocamidopropylbetaine (1% aq.) | 1.1 |

44. | Dibucaine (2.5%) | 1.1 |

45. | DMDM hydantoin (1% aq.) | 1.1 |

46. | Glutaraldehyde (1%) | 1.1 |

47. | Paraben mix (12%) | 1.1 |

48. | Black rubber mix (0.6%) | 1.0 |

49. | Di-α-tocopherol (100%) | 1.0 |

50. | Mercaptobenzothiazole (1%) | 1.0 |

51. | Tosylamide formaldehyde resin (10%) | 1.0 |

52. | Benzophenophenone-3 (3%) | 0.9 |

53. | Budesonide (0.1%) | 0.9 |

54. | Disperse blue 106 (1%) | 0.9 |

55. | Lidocaine (15%) | 0.9 |

56. | Mixed dialkyl thioureas (1%) | 0.9 |

57. | Clobetasol-17-propionate (1%) | 0.6 |

58. | Dimethylol dihydroxyethylene urea (4.5% aq.) | 0.6 |

59. | Mercapto mix (1%) | 0.6 |

60. | Sesquiterpene lactone mix (0.1%) | 0.6 |

61. | Hydrocortisone-17-butyrate (1% alc.) | 0.5 |

62. | Benzyl alcohol (1%) | 0.4 |

63. | 4-chloro-3,5-xylenol (PCMX) (1%) | 0.4 |

64. | Triamcinolone acetonide (1%) | 0.3 |

65. | Desoximetasone (1%) | 0.2 |

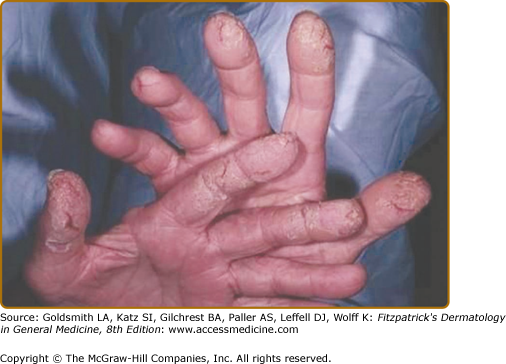

![]() A very important epidemiological fact about contact dermatitis (both irritant and allergic) is that it is the most common occupational skin disease in the United States. It is responsible for up to 30% of all cases of occupational disease in industrialized nations.8 Epidemiological data suggests that contact dermatitis accounts for 90%–95% of all skin disorders acquired in the workplace9–11 and is estimated to cost $222 million to $1 billion per year in work-related lost productivity, medical care, and disability payments in the United States alone.12 In 2008, the incidence rate of occupational skin disease in all industries was reported to be 4.4 per 10,000 full-time workers.13 More specifically, the incidence rate for occupational contact dermatitis has been suggested to be approximately 0.5 to 1.9 cases per 1,000 full-time workers per year, with a 1-year prevalence estimate of 10% and a lifetime prevalence of approximately 20%.14,15 Occupational contact dermatitis is broadly classified into allergic and irritant subtypes.16 It has been said that ACD accounts for at least 20% of the cases of occupational contact dermatitis; yet some studies have shown much higher numbers. In 2002, for example, the NACDG carried out a retrospective study on the relationship of occupation to contact dermatitis.17 Of the 5,839 patients patch tested for contact dermatitis, 1,097 (19%) were deemed to be occupationally related. Of the occupational cases, 60% were of allergic and 32% were of irritant origin (eFig. 13-0.1). The hands were the primary body part affected in 64% of allergic occupational cases and 80% of irritant occupational cases (eFig. 13-0.2). Therefore, ACD has an important public health effect, based on its frequency, and its significant economic, social, and emotional impact for the affected patient.18

A very important epidemiological fact about contact dermatitis (both irritant and allergic) is that it is the most common occupational skin disease in the United States. It is responsible for up to 30% of all cases of occupational disease in industrialized nations.8 Epidemiological data suggests that contact dermatitis accounts for 90%–95% of all skin disorders acquired in the workplace9–11 and is estimated to cost $222 million to $1 billion per year in work-related lost productivity, medical care, and disability payments in the United States alone.12 In 2008, the incidence rate of occupational skin disease in all industries was reported to be 4.4 per 10,000 full-time workers.13 More specifically, the incidence rate for occupational contact dermatitis has been suggested to be approximately 0.5 to 1.9 cases per 1,000 full-time workers per year, with a 1-year prevalence estimate of 10% and a lifetime prevalence of approximately 20%.14,15 Occupational contact dermatitis is broadly classified into allergic and irritant subtypes.16 It has been said that ACD accounts for at least 20% of the cases of occupational contact dermatitis; yet some studies have shown much higher numbers. In 2002, for example, the NACDG carried out a retrospective study on the relationship of occupation to contact dermatitis.17 Of the 5,839 patients patch tested for contact dermatitis, 1,097 (19%) were deemed to be occupationally related. Of the occupational cases, 60% were of allergic and 32% were of irritant origin (eFig. 13-0.1). The hands were the primary body part affected in 64% of allergic occupational cases and 80% of irritant occupational cases (eFig. 13-0.2). Therefore, ACD has an important public health effect, based on its frequency, and its significant economic, social, and emotional impact for the affected patient.18

On a final note about epidemiology, contact allergy caused by ingredients found in personal care products (cosmetics, toiletries) is a well-known problem, with approximately 6% of the general population estimated to have a cosmetic-related contact allergy.19,20 Contact allergy to ingredients in personal care products will be further discussed in this chapter.

Over the past decade, multiple studies have recognized contact dermatitis as an important cause of childhood dermatitis, and a common diagnosis among children; being equally as likely in childhood as in adulthood,21,22 although the most common allergens identified differ between the age groups. On the other hand, although fragrance mix allergy is an important sensitizer in all ages, certain studies, such as the 2001 Augsburg study, which was based on adults aged 28–75 years, have shown a significant increase in fragrance mix allergy with increasing age.23 Similarly, Magnusson et al24 demonstrated a high prevalence rate (4.7%) of Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru—a marker for fragrance allergy) sensitization among 65-year-old Swedish patients. Similarly, a recent Danish study demonstrated the prevalence allergy to preservatives being higher among those aged 41–60 years.25

Because very few studies have looked at the induction of allergic contact sensitization in men and women under controlled circumstances, gender differences in the development of ACD are largely unknown. When the human repeat-insult patch testing method was used to assess induction rates for ten common allergens, women were more often sensitized to seven of the ten allergens studied.26 With regard to frequency, Thyssen and colleagues found that the median prevalence of contact allergy among the general population was 21.8% in women versus 12% in men. When looking specifically at nickel sensitivity, the same study showed that the prevalence was much higher among women than men (17.1% in woman vs. 3% in men). This might be due to the fact that numerous studies have demonstrated that pierced ears are a significant risk factor for development of nickel allergy.27–31 Thus, the higher prevalence of nickel allergy in women may be explained by the higher median prevalence of pierced ears in women in comparison with men (81.5% in women vs. 12% in men) of the population studied.

The role of race, if any, in the development of ACD to some potent allergens such as para-phenylenediamine (PPD), remains controversial.32,33 Limited studies have suggested lower sensitizations rates to nickel and neomycin in African Americans compared to Caucasians. With regard to the patch-test protocol, the evaluation of positive reactions may be slightly more difficult in darker skin types (Fitzpatrick types V and VI), as erythema may not be as obvious, posing the risk of overlooking a mild positive allergic reaction. However, the edema and papules/vesicles are usually obvious and palpable; therefore palpation of the patch-test site can help to detect allergic reactions in patients with darker skin types. Finally, the darker the skin, the more difficult it is to mark the patch-test site after removal. For very dark skin, a florescent marking ink is probably best, the markings being located by a Wood’s light in a darkened room.34

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Allergic contact dermatitis represents a classic cell-mediated, delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction. Such immunological reaction, results from exposure and subsequent sensitization of a genetically susceptible host, to an environmental allergen, which on reexposure triggers a complex inflammatory reaction. The resulting clinical picture is that of erythema, edema, and papulo-vesiculation, usually in the distribution of contact with the instigating allergen, and with pruritus as a major symptom Fig. 13-1.35 To mount such reaction, the individual must have sufficient contact with a sensitizing chemical, and then have repeated contact with that substance later. This is an important distinction to irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) in which no sensitization reaction takes place, and the intensity of the irritant inflammatory reaction is proportional to the dose—concentration and amount of the irritant. In ACD, only minute quantities of an allergen are necessary to elicit overt allergic reactions. There are two distinct phases in the development of ACD: the sensitization phase and the elicitation phase.36

Most environmental allergens are small, lipophilic molecules with a low molecular weight (<500 Daltons). The unprocessed allergen is more correctly referred to as a hapten. Once the hapten penetrates the skin, it binds with epidermal carrier proteins to form a hapten–protein complex, which produces a complete antigen. Next, the antigen presenting cells (APC) of the skin (Langerhans cells and/or dermal dendritic cells), take up the hapten–protein complex and express it on its surface as an HLA-DR molecule. The antigen-presenting cell then migrates via the lymphatics to regional lymph nodes where it presents the HLA-DR–antigen complex to naive antigen-specific T cells that express both a CD4 molecule that recognizes the HLA-DR and more specifically a T-cell receptor CD3 complex that recognizes the processed antigen. The antigen can also be presented in the context of the MHC class I molecules, in which case it would be recognized by CD8 cells. Subsequently, the naive T cells are primed and differentiate into memory (also referred to as effector T cells) which undergo clonal expansion, acquire skin-specific homing antigens, and emigrate out of the lymph node into the circulation.37,38 These clones of CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ type 1 cytotoxic T cells are then able to act as effectors on target cells presenting the antigen in the future.39 The sensitization phase generally lasts 10–15 days and is often asymptomatic.40 Subsequent exposure to the antigen, or rechallenge, leads to an elicitation phase. Such rechallenge can occur via multiple routes, including transepidermal, subcutaneous, intravenous, intramuscular, inhalation, and oral ingestion.41

During this phase, both the APCs and the keratinocytes can present antigen and lead to subsequent recruitment of hapten-specific T cells. In response, the T cells release cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α, which, in turn, recruit other inflammatory cells while stimulating macrophages and keratinocytes to release more cytokines.42,43 An inflammatory response occurs as monocytes migrate into the affected area, mature into macrophages, and thereby attract more T cells. This localized proinflammatory state results in the classical clinical picture of spongiotic inflammation (redness, edema, papules and vesicles, and warmth). Recent advances in the knowledge of the pathophysiology of ACD have demonstrated the important role of the skin innate immunity in the sensitization process; have revisited the dogma that Langerhans cells are mandatory for ACD; and have addressed the nature, mode, and site of action of the regulatory T cells that control the skin inflammation (Box 13-1) (see also Chapter 10).44,45 This new understanding may facilitate the development of strategies for tolerance induction, as well as the identification of novel targets for pharmacological agents for the treatment of ACD.

Emerging evidence suggests that innate immune cells such as Natural Killer (NK) cells play a significant role in ACD. NK T cells (a hybrid between an NK cell and a conventional T cell) have been found to be necessary for the initiation of ACD and are also present in the elicitation phase of ACD. Recent studies suggest that Langerhans cells (LC) that have been credited with an indispensable role in ACD may not be essential for the development of contact hypersensitivity. New studies of mice that lack LHCs suggest that they may even play a regulatory role in ACD. Dermal dendritic cells may be the antigen presenting cells (APC) that complement epidermal LCs. T-regulatory (T-reg) cells may be critical in the control of ACD (resolution of T-cell inflammation). Loss of T-reg cell activity may play a role in chronic inflammation. Mast cells appear to be pivotal in determining the magnitude of the inflammatory reaction. Keratinocytes play a role in all phases of ACD; from the initiation phase when their production of TNF-α after antigen exposure modulates APC migration and T-cell trafficking; through the peak of the inflammatory phase when they interact directly with epidermotrophic T cells; to the resolution of ACD through tolerogenic antigen presentation and the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-16, which recruit T-regs. |

Clinical Approach

The character and distribution of the dermatitis should raise the index of suspicion for ACD. Therefore, any patient who presents with an eczematous dermatitis should be regarded as possibly having ACD (Fig. 13-2). Additionally, one must also consider contact allergy in patients with other types of dermatitis (e.g., atopic) that is persistent and recalcitrant despite appropriate standard therapies, as well as in patients with erythroderma, or scattered generalized dermatitis.46 Furthermore, it is important to note that patients with stasis dermatitis are at increased risk of developing ACD from topical medications and lotions which are often applied under occlusion over chronically inflamed and broken skin (Fig. 13-3). For that reason, ACD should always be in the differential of eczematous lesions surrounding leg ulcers. Finally, it is important to avoid some commonly held misconceptions about ACD that can alter a physician’s ability to recognize contact dermatitis. These were described by Marks and DeLeo and include the following:

- ACD is not always bilateral even when the antigen exposure is bilateral (i.e., shoe or glove allergy).

- Even when exposure to an allergen is uniform (e.g., contact allergy to an ingredient of a cream that is applied on all of the face), eczematous manifestations are very often patchy.

- ACD can and does affect the palms and the soles.

The first step in the diagnosis of ACD is a careful medical and environmental exposure history. History taking should begin with a discussion of the present illness focusing on the site of onset of theproblem and the topical agents used to treat the problem (including over the counter and prescription medications). A past history of skin disease, atopy, and general health should be routinely investigated. This is followed by a detailed history of the usage of personal care products (soap, shampoo, conditioner, deodorant, lotions, creams, medications, hair styling products, etc.), and investigation of the patient’s avocations or hobbies. The occupation should be ascertained as well, and if it appears contributory, or there are potential allergenic exposures, then a thorough occupational history should be taken. Occupations requiring frequent hand washing, glove use, or frequent chemical exposure should be prime suspects, among others.

Clinical Manifestations

The classic presentation of ACD is a pruritic, eczematous dermatitis initially localized to the primary site of allergen exposure. Geometric or linear patterns or involvement of focal skin areas, may also be suggestive of an exogenous etiology (Fig. 12-4B). A linear or streaky array on the extremities, for example, often represents ACD from poison ivy, poison oak, or poison sumac. Occasionally, the actual sensitizing substance in these plants, an oleoresin named urushiol may be aerolized when the plants are burned, leading to a more generalized and severe eruption on exposed areas such as the face and arms. Transfer of the resin from sources other than directly from the plant (such as clothes, pets, or hands) may result in rashes on unexpected sites (i.e., genital involvement in a patient with poison ivy). Thus, relevant historic data gathered from thoughtful questioning may prove as useful as the distribution of the lesions.

It is important to note that lesions of ACD will vary morphologically depending on the stage of the disease. For example, during the acute phase, lesions are marked by edema, erythema, and vesicle formation. As the vesicles rupture, oozing ensues and papules and plaques appear. Stronger allergens often result in vesicle formation, whereas weaker allergens often lead to papular lesion morphology, with surrounding erythema and edema. Subacute ACD on the other hand, will present with erythema, scaly juicy papules and weeping; whereas chronic ACD can present with scaling, fissuring, and lichenification. A key symptom for allergy is pruritus, which seems to occur more typically with allergy, than a complaint of burning.47 Moreover, there are some noneczematous clinical variants of ACD that are infrequently observed.48 These include among others:

- Purpuric ACD is mainly observed on the lower legs and/or feet and has been reported with a wide variety of allergens including textile dyes.

- Lichenoid ACD is considered a rare variant. Clinical features mimic lichen planus and has been associated with metallic dyes in tattoos. Oral lichenoid ACD from dental amalgams can resemble typical oral lichen planus.

- Pigmented ACD has been mainly described in populations from Asian ethnicity.

- Lymphomatoid ACD is based only on histopathological criteria (presence of significant dermal infiltrate displaying features of pseudolymphoma). Clinical signs which are nonspecific include erythematous plaques, sometimes very infiltrated, at the site of application of the contact allergen. Some examples include allergy to metal, allergy to hair dye, and to dimethylfumarate, a mold inhibitor found in sachets within some furniture implicated in causing a severe epidemic of ACD.

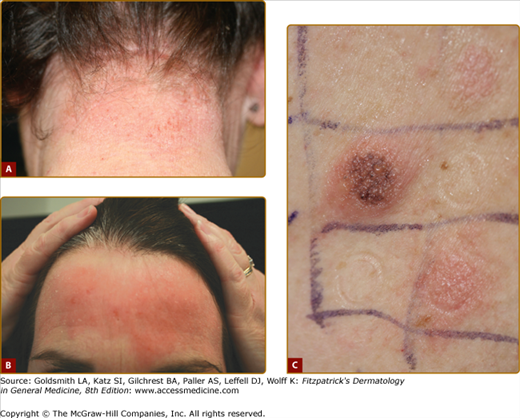

Dermatitis distribution is usually the single most important clue to the diagnosis of ACD. Typically, the area of greatest eczematous dermatitis is the area of greatest contact with the offending allergen(s). Location, in fact, can be one of the most valuable clues as to which chemical might be the culprit of a patient’s ACD. For instance, an eczematous dermatitis in the peri/infraumbilical area suggests contact allergy to metal snaps in jeans and belt buckles, whereas eczema distributed around the hairline and behind the ears suggests contact allergy to an ingredient(s) in hair products (hair dyes, shampoo, conditioners, styling products) (Fig. 13-4). Using the same rationale, eczema on the dorsum of the feet suggests contact allergy to products used to make shoe uppers like leather, rubber, or dyes, while eczematous dermatitis on the weight-bearing surfaces of the feet suggests contact allergy to products used to make insoles/soles like rubber and adhesive materials. Notably, facial, eyelid, lip, and neck patterns of dermatitis should always raise suspicion of a cosmetic-related contact allergy. However, for all of these presentations, correct identification of the culprit chemical(s) will still require patch testing, since even the most astute and experienced clinician is, for the most part, unable to properly surmise the positive allergen(s) prior to testing. The pattern of dermatitis should be mainly used in determining whether or not to patch test, and which allergens and screening series to test.

Figure 13-4

ACD to para-phenylenediamine. A. Notice the eczema on the distribution of the hairline and behind the ears. B. Dermatitis on the forehead where the bangs came in contact with the skin of the same patient. C. para-Phenylenediamine, the most frequent relevant allergen in hair dye, is a strong sensitizer. It will darken the patch-test site. There is a strong edematous and vesicular reaction that is spreading, a 3+ reaction to this patch test.

Occasionally, the topographic approach does not hold, and the distribution can actually be misleading. This mainly refers to cases of ectopic ACD or airborne ACD. Ectopic ACD can follow two circumstances: Auto transfer, in which the allergen is inconspicuously transferred to other body sites by the fingers—the classical example being nail lacquer dermatitis located on the eyelids or lateral aspects of the neck; and heterotransfer, in which the offending allergen is transferred to the patient by someone else (spouse, parent, etc.); this is described in the literature as connubial or consort ACD.

A discussion of allergens in the context of common patterns of presentation is briefly detailed below.

The face is a common site for ACD. Among patients with facial dermatitis, women are more commonly affected than men, particularly by cosmetic-associated allergens such as fragrances, PPD, preservatives, and lanolin alcohols (eFig. 13-4.1).49 Allergens can be applied to the face directly but can also be indirectly transferred from airborne or hand-to-face exposure. In addition to allergens found as ingredients in cosmetics, products used to apply them—such as cosmetic sponges, have also been reported to produce facial dermatitis in rubber-sensitive patients.50 A similar situation is seen with nickel-plated objects used on the hair, such as bobby pins and curlers that may produce scalp and facial dermatitis in nickel-sensitive patients.

Allergens applied to the scalp most often produce patterns of dermatitis on the forehead and lateral aspect of the face, eyelids, ears, neck, and hands; whereas the scalp remains uninvolved, suggesting that the scalp is particularly “resistant” to contact dermatitis. Nevertheless, patients exquisitely sensitive to certain ingredients in hair products such as PPD or glyceryl monothioglycolate may show a marked scalp reaction with edema and crusting. PPD is one of the most potent sensitizers known and is widely used as an ingredient in hair dyes. In general, PPD sensitization manifests on the face and scalp of female adult patients who had contact with a hair dye.51–54 Glyceryl thioglycolate (GMT), on the other hand, is a chemical substance used in permanent wave solutions. Allergic sensitivity to GMT can manifest as intense scalp reactions with scaling, edema, and crusting.55

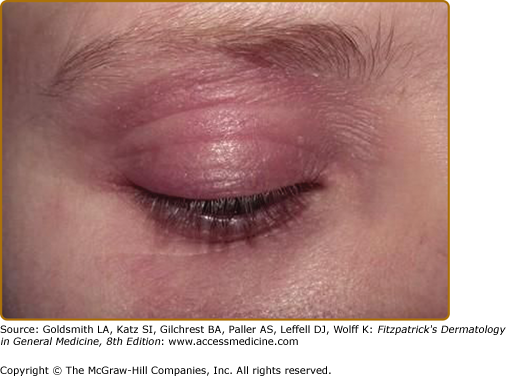

The eyelids are one of the most sensitive skin areas, and are highly susceptible to irritants and allergens perhaps due to the thinness of the eyelid skin, as compared with the rest of the skin, and perhaps because they can accumulate the offending chemical in the skin folds. Transfer of small amounts of allergens used on the scalp, face, or hands can be enough to cause an eczematous reaction of the eyelids, while the primary sites of contact remain unaltered (eFig. 13-4.2). Similarly, volatile agents may affect the eyelids first and exclusively, causing airborne eyelid contact dermatitis. Sources of contact dermatitis of the eyelids include cosmetics such as mascara, eyeliners and eye shadows, adhesive in fake eyelashes, and nickel and rubber in eyelash curlers. Furthermore, marked edema of the eyelids is often a feature of hair-dye dermatitis.56 As mentioned earlier in this chapter, eyelids are also known for being a typical site for “ectopic contact dermatitis” caused by ingredients found in nail lacquer, such as tosylamide formaldehyde resin (TSFR), the chemical added to nail varnish to facilitate adhesion of the varnish to the nail and epoxy resin, also added to some nail polishes. Topical antibiotics (like bacitracin and neomycin) and certain metals such as gold57 can also cause eyelid contact dermatitis. In fact, in the 2007 NACDG analysis of contact allergens associated with eyelid dermatitis,58 gold was the most common allergen accounting for pure eyelid dermatitis. Notably, it has been observed that upon contact with hard particles such as titanium dioxide (used to opacify facial cosmetics, and in sunscreens as a physical blocker of ultraviolet light), gold found in jewelry may abrade, resulting in the release of gold particles that can then make contact with facial and eyelid skin, causing dermatitis.59 Aside from gold, fragrances and preservatives have been found to be the main cosmetic allergens to cause dermatitis limited to the eyelids.60

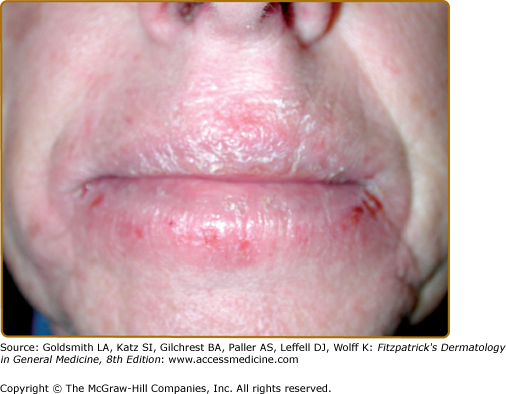

According to an NACDG study, approximately one-third of patients with cheilitis—without other areas of dermatitis—are typically found to have an allergen as a contributing factor.61,62 Allergic contact cheilitis (ACC) has been reported to result from the use of a wide array of products including cosmetics such as lip balms, lipsticks, lip glosses, moisturizers, sunscreens, nail products, and oral hygiene products (mouthwashes, toothpastes, dental floss) (Fig. 13-5).63–65 ACC has a marked female predominance, with most studies reporting a range of 70.7%–90% female patients.66 This is likely explained by the assumption that women wear more cosmetics and lip products than men. Most studies have reported fragrance allergens [such as fragrance mix and Myroxylon pereirae (Balsam of Peru)] as the most common cause of contact allergy in patch-tested patients with cheilitis.67 Of note, some uncommonly reported allergens, namely, benzophenone-3 and gallates, may be relevant to a dermatitis localized to the lips. Benzophenone-3, a major constituent of many sunscreens, is also a common ingredient in many lip products and is increasingly reported as a culprit for ACC.68,69 Gallates are antioxidants used in waxy or oily products such as lip balms, lipsticks, and lip glosses.70

The neck is also a highly reactive site for ACD. Cosmetics applied to the face, scalp, or hair often initially affect the neck. Nail-polish ingredients (tosylamide formaldehyde resin and epoxy resin) are common culprits in this region.71 Furthermore, as a cultural practice, perfumes are sprayed on the neck. In a fragrance-sensitized individual, the practice of repeated application of fragrances to the anterior neck may result in the appearance of a dermatitic plaque on the neck, which has been coined the “atomizer sign.”72 Also, in this topographic area, metal allergy can manifest as chronic eczematous dermatitis from exposure to necklaces and jewelry clasps that contain nickel and/or cobalt.

The torso can encounter fragrances, preservatives, surfactants, and other chemicals from the use of personal care products; yet it is also susceptible to allergens found in textiles. Textile-associated allergens include disperse dyes (azoanilines) and formaldehyde-releasers used as durable press chemical finishes (DPCF). In the past, finishes used to contain large amounts of free formaldehyde, which led to many cases of allergic contact dermatitis to clothing in the 1950s and 1960s. However, currently most finishes are based on modified dimethylol dihydroxyethyleneurea, which releases less formaldehyde. Importantly, recent studies have shown that the amount of free formaldehyde in most garments will likely be below the threshold for the elicitation of dermatitis for all but the most sensitive patients, and that the amount of free cyclized urea in clothes is unlikely to be high enough to cause sensitization.73

Heat, humidity, and friction of the axillary fold may contribute to the leaching of textile resins and dyes and dermatitis accentuation in these areas.74 The axillary region is also uniquely exposed to deodorants and antiperspirants. These products contain most notably the contact allergens fragrances and preservatives (formaldehyde releasers, parabens, etc.). A commonly observed effect with the use of these products is the sparing of the axillary vault, mainly secondary to perspiration diluting the allergens. Aerosolized exposure of the allergens through antiperspirant/deodorants in spray, may lead to scattering of the allergen and the resulting picture may be that of scattered satellite papules.

Hand dermatitis has a particularly high incidence secondary to the fact that the hands are the main means of interaction with the environment, with increased possibility for numerous allergen exposures. Hand dermatitis accounts for as much as 80% of the occupationally related skin diseases, especially in certain “wet work” occupations such as health care workers, food handlers, etc.75 Thus, careful consideration should be given to occupation-specific exposures in the evaluation of patients with hand dermatitis. As an example, a hairdresser may be sensitized to ingredients in hair-care products such as PPD, glyceryl monothioglycolate, or cocamidopropyl betaine (a surfactant-detergent, commonly found in shampoos), whereas a construction worker may become allergic to chromium through exposure to wet cement. Clinical clues that should raise a higher index of suspicion of ACD include the involvement of the finger web spaces and the dorsal hands, as well as the predominance of pruritus as a symptom. Still the multifactorial etiology of hand dermatitis (irritant exposure, atopy, pompholyx or chronic vesicular hand eczema, psoriasis, dermatophyte infection, among others) adds to the complexity of both diagnosing and treating these patients. Chronic hand dermatitis is an indication for patch testing, as causal or contributing allergy can result in improvement or resolution of the problem. Similarly, the evaluation of foot dermatitis should include patch testing with the allergens most commonly associated with this condition. These include, rubber-related chemicals (such as mercaptobenzothiazole, carba mix, thiuram mix, mercapto mix, black rubber mix, and mixed dialkyl thioureas) potentially present as components of shoes and insoles; glues and adhesives used in shoe manufacturing like 4-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin; and potassium dichromate found in tanned leather-made shoes. Testing materials should also include topical antibiotics, corticosteroids, or antifungal medications (both over-the-counter and prescription) that may have been used by the patient to treat the affected area.

Other topographic areas affected by ACD include the oral mucosa, which may present with contact stomatitis from dental metals and the perianal area, which may react to sensitizing chemicals in proctologic preparations such as benzocaine.

Patients with scattered generalized dermatitis (SGD) usually present a difficult diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Patch testing can be a strategy for evaluating ACD as a potential relevant factor. In 2008, Zug and NACDG colleagues 76 examined the yield of patch testing as well as the relevant allergens in patients with SGD referred for patch testing. Of 10,061 patients studied during a period of 4 years, 14.9% had SGD. Men and patients with a history of atopic eczema were more likely to have dermatitis in this distribution. Of the total of patients presenting with SGD, 49% had at least one relevant positive patch-test reaction. Preservatives, fragrances, propylene glycol, cocamidopropyl betaine, ethyleneurea melamine formaldehyde, and corticosteroids were among the more frequently relevant positive allergens.

In 2001, members of the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group (ICDRG) developed the concept of the allergic contact dermatitis syndrome (ACDS).77 This concept considers the various facets of contact allergy, including morphological aspects and staging by symptomatology. ACDS has three stages that can be defined (Table 13-1) and with many causes (Table 13-2).

Stage 1 | The skin symptoms are limited to the site (s) of application of contact allergen(s). |

Stage 2 | There is a regional dissemination of symptoms (via lymphatic vessels), extending from the site of application of allergen(s). |

Stage 3 | Can be further subdivided in Stage 3A: Corresponds to hematogenous dissemination of ACD at a distance. Stage 3B: Corresponds to systemic reactivation of ACD (nontopical trigger) |

Contact Allergena | Related Drug with Potential to Cause Systemic Reactivation of ACD |

|---|---|

Ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (stabilizer infrequently found in skin care products) | Aminophylline Piperazine antihistamines: hydroxyzine, cetirizine, levocetirizine and meclizine |

Thiuram (rubber antioxidant) | Tetraethyl thiuram disulfide (generic name: disulfiram) |

Thimerosal (mercury-derived preservative) | Piroxicam |

Systemic contact dermatitis describes a systemic reactivation of allergic contact dermatitis; in other words, a cutaneous eruption in response to systemic (nontopical) exposure to an allergen.78 In considering the chains of events resulting in the development of systemic reactivation of ACD, the ICDRG has suggested that the occurrence of some successive steps is necessary. Initially, direct skin contact with an allergen results in sensitization. Second, in some relatively uncommon cases, weeks or even years after that first episode of ACD, the patient is systemically exposed to exactly the same allergen, or to a related substance that is chemically closely related to it (cross-sensitization), elicitating a systemic reactivation of ACD. There are multiple routes of exposure for the elicitation of systemic contact dermatitis—subcutaneous, intravenous, intramuscular, inhalation, and oral ingestion. It is important then to note, that by definition, in systemic contact dermatitis, there is no occurrence of topical skin contact to the allergen. Clinically, systemic contact dermatitis has a wide spectrum of presentation, from a recall reaction (dermatitis at the site of prior topical sensitization), to widespread dermatitis and erythroderma. Other patterns that have been associated with systemic contact dermatitis include axillary vaults, upper inner thighs, and buttocks—sometimes described as “baboon syndrome,”79 which has been associated with some internally ingested allergens, i.e., cashew nut shell oil causing a cross-reaction to the allergen urushiol. Dyshidrotic hand eczema/pompholyx are conditions in which oral challenges with nickel, and Myroxylon pereirae have demonstrated flaring of this type of hand eczema in some studies (eFig. 13-5.1).80 Of particular notoriety is the allergen Myroxylon pereirae also known as balsam of Peru, a substance derived from Myroxolon balsamum, a tree that is native to the country of El Salvador. Because the main components of Myroxylon pereirae (cinnamic acid, cinnamyl cinnamate, benzyl benzoate, benzoic acid, benzyl alcohol, and esterified polymers of coniferyl alcohol) are naturally derived, they have a significant number of natural cross-reactors. Certain foods, such as tomatoes and tomato-containing products, citrus fruit peel/zest, chocolate, ice cream, wine, beer, vermouth, dark colored sodas, and spices such as cinnamon, cloves, curry, and vanilla, have chemical ingredients related to balsam of Peru.81 Consumption of these foods may result in a systemic reactivation of ACD in some patients allergic to balsam of Peru. Salam and Fowler drew attention to this ability of orally ingested balsam-related substances to induce systemic contact dermatitis, and reported that, in their study, remarkably almost half of the subjects with a positive patch test to Myroxylon pereirae who followed a balsam of Peru-reduction diet, had a significant to complete improvement of their dermatitis. Finally, some oral or IV medications may cause systemic reactivation of ACD in patients previously sensitized to related allergens by direct skin contact82–85

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree