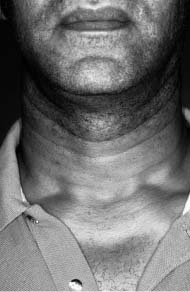

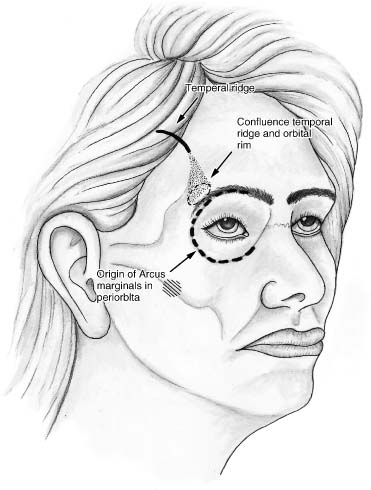

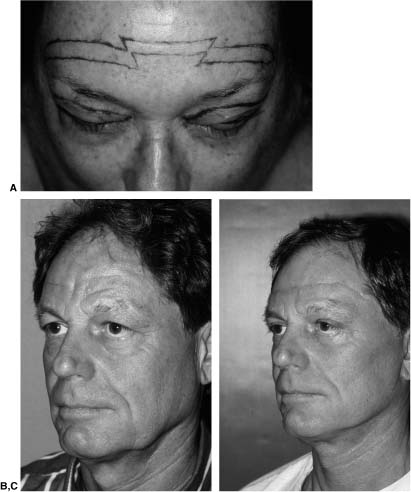

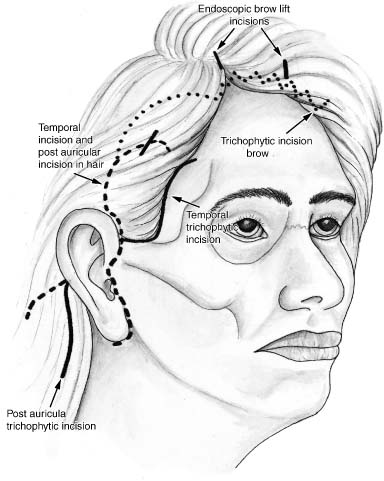

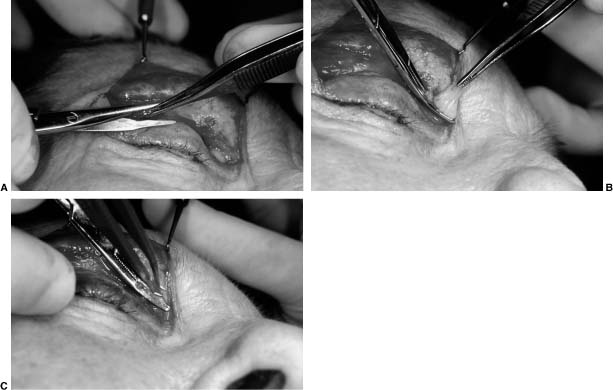

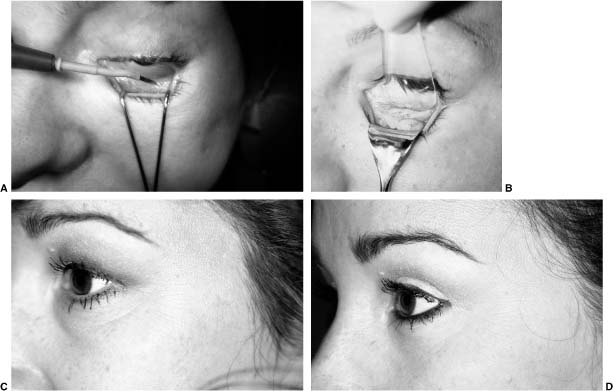

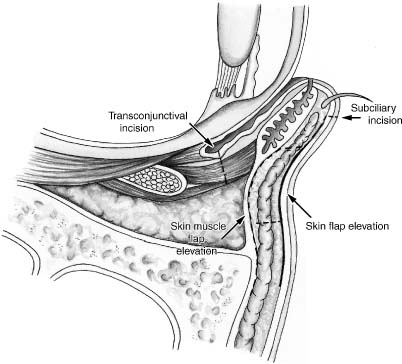

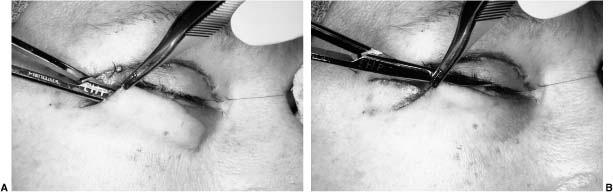

Chapter 6 As society reaches for the Fountain of Youth, there are still some physical changes that come with aging that can be postponed but cannot be eliminated by antioxidants, hydration, and exercise. It is the effect of these processes and the change in the underlying skeletal framework that makes aging-face surgery necessary to maintain youthful appearance. The causes of these changes in texture, resilience, and appearance of the skin, as well as the muscular, fascial, and skeletal support mechanisms, need to be understood and addressed in the context of the aging process. A plethora of surgical procedures have evolved to reverse this process with the goal of rejuvenation. The isolation of facial regions is useful in the evaluation, but a more global approach to the correction of these stigmata prevents facial disharmony in rejuvenation. The global approach to analysis for facial rejuvenation begins with the skin and proceeds layer by layer until skeletal abnormalities are considered. For the purpose of this chapter, the facial components are discussed with respect to their regional impact and in the context of the overall process (Fig. 6-1). There are intrinsic and extrinsic changes that occur in the skin that, in combination with congenital variations in the skeletal framework and soft tissue, lead to the characteristic changes that occur in the aging face. Intrinsic changes are generally considered changes in the substance, whereas extrinsic changes are alterations in the structure. Both processes affect the epidermis, dermis, and subcutis. Intrinsic changes may also occur in the skeletal framework. The intrinsic changes, which occur within the epidermis, include flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction, retraction of the rete pegs, changes in the size and shape of the basal cells, decreased height and adhesiveness of the keratinocytes, and loss of moisture within the stratum corneum.1 The perceived effect of these changes contributes to the fragility of the skin as one ages, as well as the roughness of texture and dryness. The fragility is usually due to the flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction and retraction of the rete pegs. Roughness is the result of loss of moisture and the thinning of the stratum corneum. The dermis itself is not immune to intrinsic changes. There is a decrease in dermal thickness that occurs throughout life, which is accompanied by an ongoing decrease in collagen content at 1% per annum. Elastic within the skin becomes atrophic, resulting in a loss of resilience, or the ability to return to its original shape after stretching. These changes lead to the laxity and redundancy of skin. The subcutis is affected by a loss of fat as time proceeds, also leading to perceived skin laxity and a gaunt, wasted appearance. Skeletal and soft tissue support of the skin also undergoes intrinsic changes contributing to the aging face. These changes may be dramatic or subtle in their effect, and may influence some of the choices made regarding surgery. Thinning of the skull, resorption of alveolar bone and descent of the hyoid bone and larynx, and buccal and temporal face resorption all impact the facial characteristics, which exacerbates the skin laxity and aging process. Congenital contributions may affect the aging process. Thicker-skinned people with increased sebaceous content tend to develop fewer wrinkles during the aging process. Increased subcutaneous fat content also helps prevent some of the subtle signs of aging within the skin. Skeletal hypoplasia affecting the cheek or chin area exacerbates the intrinsic loss of bone thickness and may have been present for life but has gone unrecognized until the patient begins to consider rejuvenation surgery. The position of the hyoid bone and larynx is variable. If in a low anterior position effacing the chin-neck angle, there will be a diminution of the surgical effect in this area regardless of platysmal suspension, submental liposuction, and cervical elevation (Fig. 6-2). Aging caused by extrinsic factors such as sun exposure, smoking, and chronic dehydration of the skin are referred to as changes in substance. These may affect the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis. Extrinsic changes, which occur in the epidermis, include dysplasia and cytologic atypia with melanocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy2 These abnormalities lead to pigmented irregularities of the skin and variations in skin texture, and may subsequently deteriorate into cutaneous malignancies. FIGURE 6-1 Multiple signs of the aging process including intrinsic and extrinsic changes in the skin, skeletal atrophy, subcutaneous fat atrophy, and buccal and temporal fat atrophy. Extrinsic changes, which occur in the dermis, include elastosis, represented by thickening and tangling of the elastin fibers, and collagen degeneration with disorganization.3 There is also a decreased vasculature in the dermis, which can contribute to the pallor of older skin. In the subcutis, there is shortening of the trabecula of the retinaculum cutis, which occurs beneath the deep rhytids. This appears to be the result of repeated muscle tone and contracture in these areas during the process of facial expression. The manifestations of the intrinsic and extrinsic aging of the skin include the exacerbation of orthostatic wrinkles, the development and deepening of dynamic or coarse rhytids, and the development of fine, crepe-paper-appearing wrinkles. Orthostatic skin creases generally represent physiologic excesses of skin present at birth such as those in the cervical region, the antecubital area, and the popliteal fossa. The deep rhytids generally become more visible due to the increase in skin laxity seen with aging, chronic folding of the skin through flexion or extension of the cervical vertebrae, and fluctuations in weight. Orthostatic rhytids are difficult to improve and may not respond to surgery (Fig. 6-3). It is occasionally difficult to distinguish among dynamic, coarse, and fine wrinkles. It is generally thought that dynamic wrinkles do not disappear with stretching of the skin and are usually caused by the muscles of facial expression and the shortening of the retinaculum cutis. Dynamic rhytids would be represented by the furrows of the glabella and the crow’s feet in the melolabial fold. This reflects the actions of the corrugators procures and orbicularis oculi muscle in the glabella area, the orbicularis oculi muscle in the lateral canthal region, and the zygomaticus major and minor, as well as the risorius and levator anguli oris in the melolabial fold and lateral oral commissure. The deep rhytids, which develop within the upper and lower lip, would reflect the action of the orbicularis oris muscle. Coarser dynamic rhytids usually require a skin tightening procedure, accompanied by resurfacing, or weakening of the muscles responsible for the overlying rhytids. FIGURE 6-2 (A,B) Anatomic contributions to the aging process including microgenia, malar hypoplasia, and a low anterior hyoid. FIGURE 6-3 Orthostatic skin creases that cannot be eliminated with rhytidectomy. The fine wrinkles that develop in the upper and lower eyelid and the buccal skin usually reflect intrinsic and extrinsic changes, which occur in the skin and disappear when the skin is stretched. These rhytids usually respond nicely to resurfacing. Increased skin laxity or loss of resilience may contribute to the gravitational changes that occur, such as malar festoons, the undulating mandibular line, and platysmal banding, and can be corrected only with surgery. In this competitive cosmetic surgical market, the initial contact with the patient during the consultation is the best opportunity to instill confidence, educate the patient, and present yourself as a compassionate, competent, well-trained professional. Aging-face patients must be made to feel special, and that your only concern is their well-being. Interruptions must be avoided. Dedicated time to allow for uninterrupted patient consultation is essential. During the consultation, it is good to have patients voice their concerns, perceptions, and expectations. This provides a foundation for assessment of their goals and evaluation of their motivation. Cosmetic surgery should not be done for someone else’s goals, only the patient’s. Realistic expectations must be emphasized and the margin of benefit for each patient evaluated. Patients must realize that a compromise is being made between the trauma of the surgery and the goal of rejuvenation. A complete history must be taken including all medications with an emphasis on the presurgical elimination of all over-the-counter medications and nutritional supplements. The exact effect on blood coagulation of many nutritional supplements is not fully appreciated. Now that younger, active, and full-time employed people are seeking cosmetic surgery, an extensive social history is imperative so that patients may be better educated about the healing process and how it will affect their daily activities, so that adequate arrangements for postsurgical assistance can be made and the impact on their work responsibilities can be assessed. The surgical recommendations can provide a customized result that will be the least intrusive on the patient’s lifestyle. As an example, someone who is unwilling or unable to avoid the sun after efforts at rejuvenation should not be offered resurfacing procedures but should be directed toward skin-tightening procedures such as a facelift or blepharoplasty. Most patients will do whatever is required for a smooth recovery if adequately educated about the reasons for avoiding overexertion, sun exposure, and premature return to work and social activities. In addition to the specific questions that are relevant to the cosmetic surgical patient, a past medical history, review of systems, and general family and surgical history should also be taken, including questions regarding bleeding disorders and problems with anesthetics. Knowledge of a patient’s previous surgical history can provide a surgeon insight into postsurgical complaints of nausea, pain, and discomfort. As a general rule, patients who have had previous surgery will not find surgery for facial rejuvenation particularly painful or unpleasant. Physical examination should begin with an overall observation of facial expression and animation while discussing the patient’s concerns. More specific evaluation of the skin type following Fitzpatrick’s classifications should be recorded. The type of skin determines the postsurgical healing and may affect the decision-making process regarding incision placement and skin resurfacing recommendations. The degree of photodamage to the skin should also be noted. This may affect the choice of treatment regimens, especially the recommendation for regional versus global facial skin resurfacing. Hair quality, texture, color, and density as well as preexisting hairline positions are also relevant in educating the patient preoperatively about the technique and incision placement in forehead, brow, and facial rejuvenation. The degree of cervical banding and submental adiposity as it relates to hyoid position should be recognized. In patients with low anterior hyoid bones, the degree of impact on the cervical facial angle with liposuction and facelift surgery is markedly compromised. If this goes unrecognized and patients are not educated preoperatively, they will, more often than not, be disappointed with the postsurgical result. Lip height, contour, and fullness should be evaluated and noted including the presence or absence of perioral rhytids and thinning of the upper and lower lip. Ear position, size, and shape, and the relationship of the lobule to the face and neck should also be recognized and reported to the patient so that surgically the relationship between the lobule and the margin of the mandible can be reestablished. Many patients do not realize that their lobules are attached, or unattached, presurgically and may see them as different after surgery if this is not brought to their attention. It is imperative to evaluate and educate the patients frankly about all their choices and surgical options so that they are empowered to make a well-informed decision. I would discourage trying to “sell” a procedure to patients even if it might offer a significant enhancement. Educating them so that they may make an informed decision to proceed or not proceed with a procedure they may not have considered previously is a much safer way to proceed. During the first consultation, patients are provided with as much information as they are able to digest. Presurgical instructions are given to patients at this time even if they have not scheduled surgery so that they have an appreciation for the need to discontinue over-the-counter medications, aspirin-containing products, and herbal dietary supplements. Photographic documentation is an integral and required part of facial plastic surgery. The photographs provide a means for evaluation and education that is unsurpassed. For these images to be of any value, they must be standardized as to framing, lighting, and patient position. Every bit as important in obtaining useful photographs as the parameters just described but much less controllable are the patient’s hairstyle, makeup, and jewelry. To gain this standardization in the initial phases of a practice, it is best for surgeons to take their own photographs and learn the techniques they wish to utilize. Once a pattern has been established and a reliable employee with an interest in photography is trained in this pattern, these responsibilities may be delegated. But the surgeon must maintain constant supervision, because the photographs must satisfy the surgeon’s need for exacting detail. The gold standard is 35-mm photography. The resolution of digital photography has continued to progress, exceeding the ability of printers to reproduce the image with the same detail with which it was originally recorded. Without a doubt, archiving and retrieving of photographs is much easier with digital photography. The main drawback with digital photography is the initial expense. Techniques for standardized photodocumentation have been laid out very well by several authors.4,5 The parameters are provided here simply as a guideline, as are the recommendations that I have found useful in simplifying my efforts to obtain standardized photography. Efforts should be made with photography to include all areas of interest while minimizing the amount of background. It is easiest to obtain this result most consistently using a 105-mm macrolens on a setting of 1 m for full face and neck photographs including rhinoplasty pictures and on 1.5 m for regional facial photographs. The F stops that provide the best exposure at these settings are 11 and 16, respectively. The camera is used on manual exposure and focus to control the parameters. When using the automatic setting, the camera has a tendency to choose a lower F stop, resulting in a shorter depth of field. Photographs are taken at 90 degrees, 45 degrees, and 0 degrees off the sagittal plane for all patients. Full-face photographs are taken with the camera oriented in the vertical position, whereas segmental photographs are taken with the camera oriented horizontally. Frequently, the most difficult thing to reproduce is patient head and eye position. Especially with blepharoplasty eye position can affect the overall perception of the result. I have been able to best obtain reproducible angle, head position, and eye position by placing targets at 90 and 45 degrees from the patient’s chair. This guarantees that if the patient focuses on these targets, the eyes will be in the same position. The chin certainly must be adjusted to align the Frankfort plane. Two sets of preoperative photographs are taken of every patient for teaching purposes. This provides a set of photographs that can be used to introduce the patient to the audience and another set of preoperative photographs to compare with the postoperative results. Digital photography has progressed to the point where a through-the-lens viewfinder is now available where standard focal distances can be set manually and where flash lighting can be utilized. With these improvements and digital photography, I would anticipate that within a matter of a few short years, standard 35-mm photography will be a matter of personal preference rather than a choice because of better quality. Regardless of whether these surgical services are provided in a hospital setting, an ambulatory surgical center or office-based surgery center, the decision making for anesthesia should not vary. Primarily it is based on the health status of the patient; subsequent to that, patient preference, anxiety level, and the skill of the anesthesiologist or the anesthetist must all be considered. Quality of care and safety outweigh any other factors under consideration. Procedures can be performed under straight local anesthesia, oral sedation with local anesthesia, monitored anesthesia care, and general anesthesia with airway intubation. The guideline in my practice is that any procedure that may take longer than 2 hours is done with a general anesthetic. I have not found topical anesthesia useful for laser resurfacing of any kind. The advantage that makes general anesthesia my preference in the office-based surgery center is control. With a well-trained anesthetist or anesthesiologist and the medications that are presently available, the risk of general anesthesia is as low or lower than monitored anesthesia care. Complete control of the patient’s airway once it is intubated provides the security that is needed for longer procedures and the airway control that may be needed for rhinoplasty. Having confidence in the skill of the endoscopist who will place the endotracheal tube is imperative. The tube should certainly be insinuated rather than forced between the vocal cords. If these parameters for intubation are followed, then the risk of dental injury or laryngeal injury are minimal and the security provided is unparalleled. For patients who are undergoing relatively minor procedures such as scar revision, skin flap, repair of soft tissue defects, isolated upper or lower lid blepharoplasty and isolated chin augmentation, these procedures are usually done under oral sedation and infiltration anesthesia. The infiltration of choice is 1% lidocaine and 1:100,000 epinephrine. When a regional nerve block would be useful in completing the procedures, it is performed prior to the time of infiltration. The guidelines for the volume of local anesthesia to be infiltrated when using plain lidocaine or lidocaine with epinephrine are followed. When more extensive procedures are contemplated and monitored anesthesia care or general anesthesia are necessary, the patients are generally not sedated prior to arriving at the office so that completion of their presurgical consultation with the anesthesiologist or anesthetist can be done in a completely alert fashion. All these patients receive a call from the anesthesiologist within 36 hours prior to their surgery in which a complete anesthesia history is taken over the phone. When procedures are being done that require more than 15 cc of local infiltration, then 0.5% lidocaine and 1:200,000 epinephrine is used. When multiple surgical procedures are being performed at the same time, regional infiltration is maintained throughout the execution of the procedure, trying to avoid reaching a toxic level of infiltrate while optimizing the vasoconstrictive effect of the epinephrine. In the development of an office-based surgery center, special consideration needs to be given to the level of anesthesia to be utilized. Regulations vary from state to state and in some instances are quite restrictive regarding requirements for monitoring medications, the level of anesthesia that can be performed, and the personnel required in the operating room and recovery area. Before investing significant money in developing an in-office operating suite, these issues should be investigated. If office space can be obtained in a building that houses an ambulatory surgery center, this is an ideal situation, reducing the initial cost of developing a cosmetic surgery practice but maintaining the convenience of an office-based surgery center. It is important to keep the agents used for infiltration as uncomplicated as possible. Seldom, if ever, is custom mixing of multiple solutions performed because it increases the possibility of error. Certainly, the supplementation of lidocaine with a longer acting anesthetic has been found useful by many physicians and is beneficial in reducing the acute postoperative pain. This may expedite patient discharge but results in an increased number of telephone calls from the patient after discharge because of unmanaged pain. As new options become available for rejuvenation of the forehead and brow, from endoscopic browlift to percutaneous brow suspension, the recommendations and decision making become more complex. Formerly, forehead and brow rejuvenation was a procedure with choices dictated more by personal preference than by the specific anatomic and cosmetic needs of the patient. But now it is a procedure with more specific indications for each technique, necessitating more detailed evaluation. It is important to emphasize that almost all patients who present for blepharoplasty consultation should be evaluated for the appropriateness and integration of forehead rejuvenation into their management. Most patients do not consider the brow or forehead to be part of the pathology affecting the upper eyelid and creating a tired, more-haggard appearance. With education of the patient regarding the impact of brow position on the appearance of the upper eye and the ability of upper eyelid blepharoplasty to rejuvenate the eye, most will be accepting of the concept and not offended by the recommendation. The importance of having a necessary browlift precede upper lid blepharoplasty has been reiterated in numerous studies, whether it precedes the blepharoplasty by hours, weeks, months, or years. When forehead rejuvenation and browlift is considered, the surgeon and patient must take into account features that would lead to the best result with the least apparent scars and postoperative sequelae. When considering the type of browlift to perform, it is important to assess the texture and quality of the hair, the position of the hairline, the status of the forehead skin, the degree of brow ptosis, and the patient’s dominant hairstyle. The lifestyle must be considered with respect to outdoor activities such as swimming and cycling, which might cause highlighting of an exposed scar. All these features affect the choice made and the direction that the surgeon should lead the patient in while making a decision. The ideal brow position and contour continues to be debated. I think a consensus has formed consistent with Cook et al’s6 recommendations (Fig. 6-4) that a more natural and less startled appearance is obtained when the arch of the brow is positioned along a vertical plane that is even with the lateral canthus of the eye. It has been recommended that the height of the arch be positioned at the lateral limbus (Fig. 6-5) occasionally led to a startled look. The actual height of the brow may be considered ptotic if it is less than 26 to 28 mm above the midpupil. Westmore has suggested that the ideal position of the lower border of the brow be equal to twice the distance of the palpebral aperture from the lower eyelid margin. These specific recommendations should be taken into consideration when determining the ideal brow position with respect to the aesthetics of the patient as well as the contour of the brow at a younger age. Marked change in the contour of the brow beyond its elevation may be unsatisfactory for the patient. FIGURE 6-4 Arch of the brow positioned along a vertical plane at the lateral canthus as recommended by Cook. FIGURE 6-5 Positioning of the arch of the brow at the lateral limbus may lead to a more startled appearance. FIGURE 6-6 Ideal candidate for endoscopic brow lift with low frontal hairline. Patients with a low frontal hairline are best managed with either a coronal or endoscopic browlift (Fig. 6-6). Both these lifts reposition the frontal hairline more superiorly. The distinction between endoscopic browlift and coronal browlift is based on hair quality and texture and the functional degree of ptosis. In a patient whose brow ptosis creates a functional problem with the upper eyelid and peripheral vision, the recommendation should be for coronal browlift where the more time-tested technique with the excision of scalp provides a more predictable duration to the brow elevation. The full coronal lift is better tolerated in people with thin, salt-and-pepper hair. If any alopecia at the incision does develop, then the contrast between the bald incision and the hair-bearing scalp is minimal and imperceptible in most cases. For patients with brow ptosis that does not present a functional problem, and for patients with darker, thicker hair, endoscopic browlift is preferred. If any alopecia does develop, it is separated from adjacent incisions. Generally, endoscopic lift incisions are directed parallel to natural parts in the hair and can be easily camouflaged. Endoscopic browlift is indeed a technique that can yield dramatic brow elevation, but further studies are needed to determine whether it will stand the test of time as the coronal lift has. For patients with a high frontal hairline, there are two surgical approaches I find acceptable: the trichophytic incision within the frontal hairline and the midforehead approach. The choice may depend on hairstyle but more importantly on the depth of the forehead rhytids. The trichophytic browlift is performed with a broken-line incision following the random pattern of the frontal hairline (Fig. 6-7). The incision is beveled inferiorly so that any random hairs that may be growing outside of the hairline will have the opportunity to regrow through the incision by amputation and preservation of the follicle. The amount of elevation is measured and the amount of skin to be excised is predetermined and marked. This is the best way to guarantee the pattern interdigitation after excision. FIGURE 6-7 Broken-line trichophytic incision for patients with a high temporal and frontal hairline. FIGURE 6-8 (A) Midforehead incision for patients with high frontal hairline and deep forehead rhytids. (B) Preoperative. (C) One-year postoperative. For patients with a high frontal hairline or a receding hairline and deep midforehead rhytids, a midforehead browlift is performed with excision of one or more forehead rhytids (Fig. 6-8). This incision is best interrupted at the midline or paramedian position depending on personal preference. The third option available for patients with a high frontal hairline or male pattern baldness is a direct browlift. This procedure is most useful in facial paralysis patients where specific sculpting of the brow is necessary to match the opposite side and where a scar at the upper edge of the brow, which may be perceptible, is less of a distraction. Otherwise, the direct lift is seldom used. Other approaches to browlift include a midforehead extension of a trichophytic facelift incision or lateral brow elevation with an incision within the temporal tuft of hair (Fig. 6-9). These procedures are usually applied when only lateral elevation is necessary, and have been done when inadequate lateral brow elevation has been obtained with coronal, endoscopic, or a trichophytic lift. The anatomy of the scalp and forehead is extremely consistent and uncomplicated. The layers of the forehead reflect the anatomy at the scalp, with the galea aponeurosis reflecting the connective tissue capsule over the frontalis muscle. The galea then extends posteriorly and superiorly to connect with the occipitalis posteriorly. The supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves provide the sensory innervation of the forehead and anterior scalp. The supraorbital nerve is routinely found at a level along the superior orbital rim even with the pupil. The supraorbital nerve may or may not exit through a foramen. Most frequently it exits the orbit through a notch at the orbital rim, which can be palpated through the skin. In some patients the nerve exits directly through a foramen, and for this reason, if no notch is palpated in the orbital rim, endoscopic visualization should be maintained while dissecting in the supraorbital area to prevent trauma or avulsion of the supraorbital nerve. The supratrochlear nerve exits the orbit medially ~2 cm from the midline and traverses the corrugator muscle prior to reaching the deep surface of the frontalis and penetrating it. The supraorbital nerve may penetrate the frontalis immediately to run on the superficial surface of the frontalis muscle, or it may penetrate at varying heights up above the brow, and this is why care must be taken when the frontalis is divided beneath the deep forehead rhytids. FIGURE 6-9 Lateral temporal lift with partial midforehead and trichophytic temporal incision. The temporalis muscle is bounded anteriorly and superiorly by the superior temporal ridge (Fig. 6-10). Beneath the subcutaneous tissue is the temporoparietal fascia, which is analogous to the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia. This fascia is consistent with the periosteum over the frontal bone at the superior temporal line. Within the temporoparietal fascia lies the frontal branch of the facial nerve as it courses across the midzy-gomatic arch and extends superiorly in the temporoparietal fascia toward the deep surface of the frontalis muscle. The frontalis muscle acts to elevate the brow and has its origin in the fascia of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The remaining periorbital muscles, including the paired corrugator supercilii, procerus, and orbicularis oculi muscle, act as brow depressors. The periosteum over the frontal bones extends inferiorly and becomes continuous with the periorbita at the arcus marginalis. When subperiosteal elevation is performed with endoscopic, trichophytic, or coronal browlift, it is imperative that the arcus marginalis be divided to allow mobilization of the brow superiorly. There are several general rules that apply to browlift and elevation. The more remote the incision for a browlift, the larger the amount of tissue that must be resected. As described by Ferdinaud Becker, an excellent rule of thumb is two times the desired brow elevation for a coronal lift, 1 1/2 two times the desired elevation for a trichophytic lift, and 1 1/2 times the desired elevation for a midforehead lift. In addition, the more remote the incision, the deeper the plane of elevation. For a coronal or endoscopic lift, the plane of elevation is generally subgaleal or subperiosteal. Because of the shear between the galea and the periosteum, I have found that subgaleal elevation provides a better mobilization and long-term result. The trichophytic incision (Fig. 6-11) is also accompanied by an endoscopic subgaleal elevation following subcutaneous skin excision. Because of the adherence of the galea to the periosteum and the supraorbital and glabellar areas, frequently it is necessary to elevate a subperiosteal plane from ~2 cm above the orbital rim, inferiorly dividing the periosteum and the arcus marginalis at the orbital rim (Fig. 6-12). The periosteum, if elevated inferiorly, must be divided centrally so that the corrugator and procerus muscles can be identified and avulsed. If care is not taken, multiple planes can be violated in the glabella and supraorbital areas, creating confusion and disrupting visibility. When attempting to remain subgaleal for the entire elevation, visualization during elevation is necessary. Subperiosteal elevation can be done to just above the orbital rim without visualization. FIGURE 6-10 The interdigitated temporoparietal fascia and the periosteum at the inferior portion of the temporal ridge adjacent to the orbital rim are extensive and require meticulous dissection to assure release at this point. Midforehead, temporal, and direct browlifts are elevated in a subcutaneous plane. This elevation extends down to the superior margin of the brow, occasionally encountering follicles of the brow. Centrally, the subcutaneous tissue and frontalis muscle are divided so that the corrugator and procerus can again be avulsed. After this is performed, the orbicularis oculi muscle at the superior margin of the brow is suspended to the periosteum with interrupted Maxon sutures at positions on the brow that are even with the medial limbus, lateral limbus, and lateral canthus. After orbicularis oculi muscle suspension is completed, these skin flaps are redraped and marked, and redundant skin is excised. Hemostasis is always obtained with bipolar electrocautery, and care is taken not to injure the supraorbital nerve with the suspension suture. With coronal, trichophytic, and endoscopic browlift, more extensive lateral elevation is performed. The temporalis fascia is identified and the temporoparietal fascia or superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia is elevated. This elevation extends into the temporal fat down to the zygomatic arch and malar eminence. The periosteum is incised and periosteum elevated off the malar eminence and zygomatic arch. Prior to incision of the periosteum of the malar eminence, the sentinel vein is identified, which is usually present at the level of the lateral canthus 1 cm lateral to the orbital rim. Care is taken to preserve this vein because it is found adjacent to the frontal branch of the facial nerve superficially within the temporoparietal fascia. Frontalis muscle may be divided beneath the deep forehead rhytids with care taken to avoid the supraorbital nerve. Suspension of the brow is obtained through scalp or forehead skin excision with the coronal or trichophytic browlift, respectively. With an endoscopic browlift, suspension must be obtained with complete subgaleal elevation over the vertex and occiput as well as laterally at the superior and posterior temporal ridge (Figs. 6-10 and 6-12). After complete elevation is accomplished, suspension can be obtained with monocortical screws, which may be titanium or absorbable, or with suture suspension to a bone bridge. With screw fixation, titanium screws may be left in place or removed. These screws have been used percutaneously, which expedites removal at 3 weeks. With these procedures, complete release of the arcus marginalis lateral to the supraorbital nerves is essential. FIGURE 6-11 Incision sites for approaches to the brow and face. With a low or intermediate frontal hairline position, endoscopic or coronal decisions can be made for the browlift. With a high frontal airline, a trichophytic incision is usually made. Hairline position also determines placement of the temporal portion of the facelift incision. The position of the postauricular hair incision is determined by the degree of cervical skin laxity; if minimal laxity is present, the decision is extended into the hair. When extensive cervical laxity is present, the incision is made in a trichophytic fashion. The most tedious part of these dissections is release of the arcus marginalis and galeal-periosteal complex at the junction of the superior orbital rim and the superior temporal line (Fig. 6-12). This is the point where the frontal branch of the facial nerve is most vulnerable. Careful blunt and sharp dissection is used most often proceeding from the posterior flap beneath the temporoparietal fascia, which interdigitates with the periosteum at the temporal line through a conjoint tendon (Fig. 6-12). All browlifts are accompanied by a dressing for 24 hours. Complications from brow and forehead rejuvenation include alopecia, numbness, bleeding, infection, frontal nerve paralysis, and paresthesias. The subcutaneous forms of the procedure such as the midforehead, direct, and temporal incisions are less likely to be accompanied by numbness and should not cause alopecia. The trichophytic and coronal lift cause acute postoperative numbness, which may resolve. Patients are informed that this numbness will occur in the acute postoperative period and that it may not resolve, so that if resolution does not occur they are not disappointed. The endoscopic brow and forehead lift can be accompanied by numbness, but it is much less likely to occur and it should completely resolve. Occasional paresthesias and phantom sensations can occur posterior to the coronal or trichophytic incisions. Rejuvenation of the eyelids is the first procedure considered by most patients. The limited nature of the surgery, the short recovery period, and the obviously evident early deterioration of lid skin make blepharoplasty an easy choice as a first cosmetic procedure. A review of the medical-surgical history involving the eye focus on glaucoma, dry eye syndrome, or corneal surgery. During the physical exam, contributing factors such as brow ptosis, lacrimal ptosis, and ptotic fat that might contribute to an unsatisfactory result must be evaluated. The degree of lower lid laxity must be assessed. If the lid can be retracted more than a centimeter away from the globe or does not snap back adjacent to the globe immediately upon its release, some form of resuspension should be considered. FIGURE 6-12 The planes of elevation for browlifting are consistent with an initial subgaleal elevation over the superior forehead and a subperiosteal elevation initiated 2 cm above the orbital rim. Lateral elevation is to the temporoparietal fascia on the true temporal fascia. For a mid-forehead browlift the elevation is in a deep subcutaneous plane. Discussion of blepharoplasty requires clarifying the terminology used to describe abnormalities of the upper and lower eyelid. Variations of two distinct conditions may be present. The senile changes that occur in the upper and lower eyelid include dermatochalasis, which reflects relaxation of the skin accompanied by varying amounts of fat pseudoherniation or prolapse (Fig. 6-13). In contrast, blepharochalasis is an infrequent disorder in young people associated with swelling and edema of the lids with progressive tissue breakdown, which leads to prolapse of the orbital fat and possibly the lacrimal gland (Fig. 6-14). FIGURE 6-13 Patient with dermatochalasis of the upper and lower eyelid with senile pseudoherniation of fat from the lower eyelid. Orbital anatomy is integrally related to the deformity appreciated at the time of examination and should be taken into consideration during surgical planning and execution to achieve the most ideal result and to prevent complications. The bony orbit is composed of contributions from the frontal, zygomatic, maxillary, sphenoid, palatine, lacrimal, and ethmoid bones. The size of the orbit and the position of the orbital rim may vary from one side to the other and should be noted pre-operatively. FIGURE 6-14 Blepharochalasis exaggerated on upward gaze in a patient with congenital edema. The lids themselves are composed of skin, subcutaneous tissue, three muscles (orbicularis, Müller’s, and levator), and varying degrees of fat, tarsus, and conjunctiva. The lid crease or palpebral fold is created by the insertion of the levator aponeurosis and the orbital septum into the orbicularis oculi muscle at the upper edge of the tarsal plate. In the occidental upper eyelid the levator aponeurosis inserts along the tarsal plate with few distinct connections to the orbicularis and skin. Skin beneath the palpebral crease, the pretarsal skin, is usually very thin and has a varying degree of mobility. The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle above the lid crease contribute to the lid fold. The orbicularis oculi muscle includes a pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital components. The pretarsal orbicularis oculi muscle fused to form the medial canthal tendon attached to the anterior lacrimal crest superiorly and the posterior crest inferiorly The preseptal portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle is the portion that is most frequently modified with upper lid blepharoplasty. It is important with lower lid blepharoplasty to preserve the pretarsal orbicularis oculi muscle as completely as possible. The orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle superiorly contributes to the fullness and thickness of the skin beneath the brow and is better addressed with brow elevation. Deep to the orbicularis oculi muscle is the tarsal plate and orbital septum. The septum is a continuation of the periorbita and arcus marginalis to the peripheral margin of the tarsal plate of the upper or lower eyelid. It may weaken with age, resulting in a pseudoherniation of fat. The tarsal plate is a fibrous plate about 8 to 10 mm wide in the upper lid and 3 to 5 mm wide in the lower lid. It extends from the lateral canthal tendon to the medial canthal tendon and punctum and is lined on its deep surface by conjunctiva. Upper lid blepharoplasty may need to address skin laxity, thickened orbicularis oculi muscle, or possibly herniation of the medial and central fat compartments. Ptosis of the lacrimal gland can also be corrected if recognized. The technique for upper lid blepharoplasty may include the predetermination of the skin to be excised or elevation of a flap with excision of redundant skin at the time of surgery. FIGURE 6-15 Marking for upper lid blepharoplasty with the patient in the upright position. (A) The inferior incision is in the palpebral crease. (B) Determining the resected amount with the head in a neutral position and eyes closed to avoid over-resection. With the patient in the upright position prior to infiltration with anesthesia, the upper eyelid is marked at the tarsal crease or palpebral fold usually extending lateral to the lateral canthus for ~1.5 cm. After the tarsal crease is marked, the lid is pinched and the amount of skin to be excised is predetermined and marked (Fig. 6-15). If orbicularis hypertrophy is appreciated, then the pretarsal orbicularis muscle is resected in conjunction with the skin. After resection of the upper eyelid skin and muscle, the orbital septum is divided medially and centrally with the resection of herniating fat. Protruding fat is first cross-clamped with a hemostat, resected, and the stump of the fat cauterized with bipolar electrocautery (Fig. 6-16). This can be performed with a CO2 laser if desired. If the only pathology of the upper eyelid is excess skin, then the skin is trimmed and the wound is closed with a running subcuticular nylon suture. In lower eyelid blepharoplasty there are more options available to address the specific pathologic changes that might be present from simple dermatochalasis to lid laxity, festoons, and ectropion. The surgical procedure is customized to deal with the pathology present and optimize the results. The decision is based not only on the degree of dermatochalasis but also on the degree of orbicularis hypertrophy, the amount of pseudoherniation of fat, the tone in the lower eyelid, and the patient’s personal preferences. If dermatochalasis is the primary pathology to be addressed, then a skin muscle flap or laser resurfacing of the lower eyelid would be the primary treatment choice (Fig. 6-17A). For patients with extensive pseudoherniation of fat as well as dermatochalasis, a skin muscle flap with fat excision or transconjunctival blepharoplasty with laser resurfacing is the primary recommendation (Fig. 6-17B). For patients with a subciliary ridge due to orbicularis hypertrophy, a skin muscle flap with trimming of the orbicularis oculi muscle and skin excision with orbicularis resuspension provides the optimal result. Of patients in the first two categories where laser resurfacing might be considered, if the patient’s lifestyle necessitates an early return to function, then the surgical approach with skin excision is the method of choice. If, however, the patient has the need to address facial or perioral rhytids and laser resurfacing is to be used elsewhere on the face, then the transconjunctival approach with fat excision and laser resurfacing of the eyelid is performed. A transconjunctival blepharoplasty with the pinch technique and excision of lower lid skin is also an option that does not disrupt the pretarsal orbicularis muscle. FIGURE 6-16 Upper lid blepharoplasty. (A) Resection of a strip of orbicularis muscle at the palpebral crease beginning at the lateral canthus. (B) Resection of fat in the medial upper eyelid with cross-clamping. (C) Cautery of the pedicle. Maintaining the continuity of the pretarsal orbicularis muscle is important in avoiding the most common postoperative complication of ectropion. Special modifications of the skin muscle flap are made to try to preserve the pretarsal orbicularis. In performing upper and lower blepharoplasty with skin excision or with laser resurfacing, it is extremely useful to place a tarsorrhaphy suture at the midpupillary line to stabilize the lids, provide improved retraction, protect the cornea, and prevent excess skin resection. When transconjunctival blepharoplasty is being done in conjunction with upper lid blepharoplasty, the transconjunctival fat excision is performed first, and then the tarsorrhaphy sutures are secured to protect the globe during laser resurfacing and to stabilize the upper lid for incision and excision of skin. FIGURE 6-17 The appropriate lower lid blepharoplasty is determined based on certain physical and anatomic features. (A) Patient appropriate for lower lid blepharoplasty with various techniques including transconjunctival fat excision and pinch techniques, laser resurfacing or a skin muscle flap. (B) Pseudoherniation of fat with minimal to no dermatochalasis in an excellent candidate for transconjunctival blepharoplasty. (C) Dermatochalasis and pseudoherniation of fat with loss of tone in the lower eyelid requiring skin and fat excision with suspension of the lower eyelid. (D) Moderate dermatochalasis with extensive midface ptosis, deep nasal jugal groove, good lower eyelid tone, and pseudoherniated fat representing an ideal candidate for a suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) lift. Transconjunctival blepharoplasty is performed in the patient who has a primary pathology of fat protrusion and minimal to no dermatochalasia (Fig. 6-18). The lower eyelid is infiltrated with 1% lidocaine and 1:100,000 epinephrine including an infraorbital nerve block and conjunctival infiltration. When this is done under local anesthesia, it is helpful to anesthetize the conjunctiva with a topical ophthalmic anesthetic agent. After anesthesia is obtained, the Yaeger plate is used to place pressure on the globe and an insulated Desmarres retractor used to retract the lower eyelid. The inferior orbital rim is palpated and a fine-tip electrocautery needle is used (Fig. 6-18A). An open sky incision is made through the conjunctiva from central to lateral. This is performed down to the orbital rim without incision in the periosteum of the orbital rim. At this point, the fat frequently herniates and is apparent in the wound. If portions of the orbital septum persist, bipolar electrocautery is used to divide the vasculature within the septum, and it can then be further separated using electrocautery or tenotomy scissors. Immediately after incision of the conjunctiva, the conjunctiva is sutured with a draw suture of 3-0 silk to protect the globe superiorly. This is stabilized through the head dressing with a hemostat. After the conjunctiva is stabilized superiorly over the globe, medial, central, and lateral fat compartments are identified; herniating fat is cross-clamped with a hemostat and the fat excised. Once fat excision is completed, the base of the herniating fat is cauterized with bipolar electrocautery. The hemostat is then gradually released and maintained in place to act as a retractor of the adjacent soft tissues, and the visible portion of the stump is again cauterized. The central and lateral fat compartments are then addressed in the same way. In the central fat compartment, it is important not to dissect into the orbit without identification of the inferior oblique muscle. If fat herniation occurs anterior to the orbital rim, then it is not imperative to identify the inferior oblique muscle. The lateral fat compartment is sometimes the most difficult to identify and to resect the fat from during a transconjunctival blepharoplasty. Once the surgeon believes that adequate fat has been resected, the lower lid is released and repositioned over the globe. Pressure on the orbit will reveal any residual fat that might represent a problem postoperatively. This segment may then be read-dressed if necessary (Fig. 6-18C,D). FIGURE 6-18 Transconjunctival blepharoplasty. (A) Lid retraction and subtarsal transconjunctival incision. (B) Lid retraction and global pressure with a Yeager plate creating herniation of orbital fat. (C) Preoperative. (D) One year postoperative. When excessive dermatochalasis is apparent and the transconjunctival approach is chosen for fat excision and with laser resurfacing to address the dermatochalasis, the tarsorrhaphy suture is placed after excision of the lower eyelid fat. After the tarsorrhaphy suture is secured, excessive upper eyelid skin is resected and the upper eyelid completed. Laser resurfacing is then performed with vaporization of the deep rhytids that had been marked prior to surgery. After the deep rhytids have their margins vaporized, the entire lid is resurfaced in two passes while tapering at the margin of each pass. When an incisional approach is made (Fig. 6-19) for lower eyelid blepharoplasty, a subciliary incision is made 2 to 3 mm beneath the lash margin, maintaining an isthmus at the lateral canthus of 6 to 7 mm between the lower and upper eyelid incision and extending ~1 1/2 in an inferior lateral direction from the lateral canthus following a natural skin crease (Fig. 6-20A). This usually brings the lateral extent of the lower eyelid incision immediately over the lateral portion of the lateral rim. When a moderate degree of dermatochalasis or orbicularis hypertrophy is encountered and a skin muscle flap is the technique to be used, tenotomy scissors are inserted with division of the orbicularis oculi muscle beneath the lateral extent of the skin incision. Suborbicularis elevation is then performed bluntly with the tenotomy scissors over the orbital rim. At this point, one blade of the tenotomy scissors can be inserted into the suborbicularis pocket (Fig. 6-20B) inferiorly with the other blade maintained at the subciliary incision. It is then easy to maintain a preseptal elevation of the orbicularis oculi muscle by incrementally advancing and closing the scissors, maintaining the superior blade of the scissors beneath the lashes in the subciliary incision. The scissors are beveled inferiorly to preserve the preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle. After the incision is completed, any persistent connections between the orbital septum and orbicularis muscle are divided. Hemostasis is obtained at this point with electrocautery. The skin muscle flap is then retracted inferiorly. Medial, central, and lateral fat compartments are addressed as described with a transconjunctival blepharoplasty. The skin muscle flap is then redraped. If the patient is awake, the mouth is opened. The skin is marked and excess skin excised using the tenotomy scissors. At the time of skin excision, the blade of the scissor beneath the orbicularis oculi muscle is turned inferiorly to resect some orbicularis oculi muscle from beneath the skin of the lower eyelid so that there is no overlap of preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle causing duplication of the muscle. FIGURE 6-19 Incisions for approaches in lower lid blepharoplasty. FIGURE 6-20 (A) Blunt dissection after subciliary incision in a submuscular plan. (B

AGING-FACE SURGERY

PATHOGENESIS

CONSULTATION AND ANALYSIS

PHOTOGRAPHY

ANESTHESIA

PROCEDURES

REJUVENATION OF THE FOREHEAD AND BROW

Anatomy

Complications

BLEPHAROPLASTY

Upper Lid Blepharoplasty

Lower Lid Blepharoplasty

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree