20

Acute Nerve Laceration

Kevin D. Plancher

History and Clinical Presentation

A 20-year-old right hand dominant male laborer caught his left hand in a circular saw with the “guard” off. He has a laceration to his left index finger and can’t feel the tip of his finger, and has an open bleeding wound.

Physical Examination

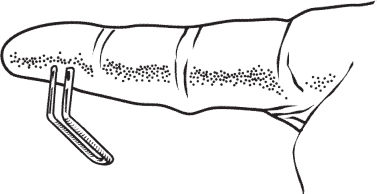

On physical examination, the patient has an acute open laceration involving the radial side of the right index finger. A careful motor examination was performed. The functioning level of specific muscles is determined to assist with identifying peripheral nerve injuries. A two-point sensory discrimination test (Fig. 20–1), as determined by the Weber two-point discrimination test, using a dull pointed eye caliper applied in the longitudinal axis of the digit without blanching the skin, and a two-point discrimination (2-PD) (both moving and static), Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments, and vibrometer tests were used to assess the status of the nerves. Denervated skin responds differently to stimuli; when the injured hand is placed in water, innervated skin wrinkles and denervated skin does not. This test can be helpful in determining the affected peripheral nerves in the hand in unconscious patients.

Diagnostic Studies

Radiographs were performed to rule out associated fractures.

PEARLS

- Microscopic repair is always more accurate.

- Occupational therapy post-operatively will successfully complete a desensitization program.

- The area of injury must be defined for successful functional nerve repair.

PITFALLS

- Clean ends of nerve must be sewn together to avoid a neuroma in continuity.

- Missed diagnosis with a devascularized finger may lead to amputation

- Range of motion must be controlled with splinting.

Differential Diagnosis

Vascular injury

Muscle laceration

Neurologic disorder

Nerve laceration

Figure 20–1. Weber static two-point sensory discrimination test.

Diagnosis

Acute Laceration, Radial Nerve, of the Index Finger

Neurapraxia is the mildest form of nerve injury. This usually involves demyelination without axon disruption and degeneration. This type of injury has a relatively short recovery time, and full function is expected without intervention.

Axonotmesis occurs when axons, myelin, and associated internal nerve structures are disrupted. These injuries often result from situations in which traction overcomes the inelastic internal structures but leaves the elastic epineurium intact. When axons are disrupted and the endoneurium and the rest of the nerve are intact, degeneration and regeneration occur. This is the first stage of injury that shows an advancing Tinel’s sign. Because the endoneurium is intact, regeneration should be full with complete sensory and motor function regained.

Another type of injury occurs when the axons and the endoneurium are damaged and the perineurium and epineurium are intact. This leaves the blood–nerve barrier intact but provides a disorganized bed through which the axons can travel. Nerve regeneration may be slowed due to infiltration of scar tissue or a smaller number of axons capable of survival and regeneration. An advancing Tinel’s sign, though some-what slowed, should be present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree