Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis (Sweet Syndrome): Introduction

|

History

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis was originally described by Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet in the August–September 1964 issue of the British Journal of Dermatology. The cardinal features of “a distinctive and fairly severe illness” that had been encountered in eight women during the 15-year period from 1949 to 1964 were summarized. Although the condition was originally known as the Gomm–Button disease “in eponymous honor of the first two patients” with the disease in Dr. Sweet’s department, “Sweet’s syndrome” has become the established eponym for this acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.1–10

Epidemiology

More than 1,000 cases of Sweet syndrome have been reported since Sweet’s original paper.1–509 The distribution of Sweet syndrome cases is worldwide and there is no racial predilection.1,2,12,16–20,30,31 The dermatosis presents in three clinical settings.13,15

Diagnostic criteria for classical or idiopathic Sweet syndrome were proposed by Su and Liu in 1986 and modified by von den Driesch in 1994 (Table 32-1).11–14 It may be associated with infection (upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract), inflammatory bowel disease, or pregnancy.13,15 Two studies have noted a seasonal preference for the onset of Sweet syndrome for either autumn or spring in 70% of 42 patients.416 or autumn.496

Classicala | Drug Inducedb |

|---|---|

| (1) Abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules | (A) Abrupt onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules |

| (2) Histopathologic evidence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis | (B) Histopathologic evidence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis |

| (3) Pyrexia >38°C | (C) Pyrexia >38°C |

| (4) Association with an underlying hematologic (most commonly acute myelogenous leukemia) or visceral malignancy (most commonly carcinomas of the genitourinary organs, breast, and gastrointestinal tract), inflammatory disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) or pregnancy, or preceded by an upper respiratory (streptococcosis) or gastrointestinal (salmonellosis and yersiniosis) infection or vaccination | (D) Temporal relationship between drug ingestion and clinical presentation or temporally related recurrence after oral challenge |

| (5) Excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide | (E) Temporally related resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids |

| (6) Abnormal laboratory values at presentation (three of four): erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/hour; positive C-reactive protein; >8,000 leukocytes; >70% neutrophils |

Classical Sweet syndrome most commonly occurs in women between the ages of 30 to 60 years. However, classical Sweet syndrome also occurs in younger adults and children.32–48,405,415,445,447,453 The youngest Sweet syndrome patients are brothers who developed the dermatosis at 10 and 15 days of age.46

Several investigators consider it appropriate to distinguish between the classical form and the malignancy-associated form of this disease since the onset or recurrence of many of the cases of Sweet syndrome are temporally associated with the discovery or relapse of cancer.15,49–60 Recently, the investigators of a comprehensive review of 66 pediatric Sweet syndrome patients observed that 44% of 30 children between 3 and 18 years of age had an associated hematologic malignancy.405,447 Malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome in adults does not have a female predominance and is most often associated with acute myelogenous leukemia.61,62 In Sweet syndrome patients with dermatosis-related solid tumors, carcinomas of the genitourinary organs, breast, and gastrointestinal tract are the most frequently occurring cancers.1,2,63–66

Criteria for drug-induced Sweet syndrome were established by Walker and Cohen in 1996 (Table 32-1).13 This variant of the dermatosis is most frequently observed to occur in association with the administration of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF).1,2,13,67,68 However, several other medications have also been implicated in eliciting drug-induced Sweet syndrome (ch32etb1.1).11,13,17,39,41,69–124,401,402,422,427–429,436,437,439,446,455,456,463,464,468,469471,474,476,477,482,487, 489,490,492,493,505,506

Medication | References |

|---|---|

Abacavir | |

Acyclovir | |

All-trans retinoic acid | |

Amoxapine | |

Azathioprine | |

Bortezomib | |

Carbemazepine | |

Celecoxib | |

Chloroquine | |

13-cis retinoic acid | |

Citalopram | |

Clindamycin | |

Clozapine | |

Contraceptives | |

Diazepam | |

Diclofenac | |

Doxycycline | |

Erythropoietin | |

Furosemide | |

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor | |

Granulocyte–macrophage-colony stimulating factor | |

Hydralazine | |

Imatinib mesylate | |

Interferon α (pegylated) | |

Lenalidomide | |

Levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol (Triphasil) | |

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) | |

Minocycline | |

Nitrofurantoin | |

Norfloxacin | |

Ofloxacin | |

Pegfilgrastim | |

Perphenazine | |

Phenylbutazone | |

Piperacillin/tazobactam | |

Propylthiouracil | |

Quinupristin/dalfopristin | |

Radiocontrast agent | |

Ribaflavin | |

Sulfa | |

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome may be multifactorial and remains to be definitively determined. A condition, similar to Sweet syndrome, presenting as a sterile neutrophilic dermatosis, has been described in a female standard poodle dog after treatment with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug firocoxib and in multiple dogs temporally associated with the administration of carprofen.403

Sweet syndrome may result from a hypersensitivity reaction to an eliciting bacterial, viral, or tumor antigen.2,127 A septic process is suggested by the accompanying fever and peripheral leukocytosis. Indeed, a febrile upper respiratory tract bacterial infection or tonsillitis may precede skin lesions by 1–3 weeks in patients with classic Sweet syndrome. Also, patients with Yersinia enterolitica intestinal infection-associated Sweet syndrome have improved with systemic antibiotics.2,77,125–127

The systemic manifestations of Sweet syndrome resemble those of familial Mediterranean fever. Recently, the simultaneous occurrence of both conditions has been observed.421 Also, in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia-associated Sweet syndrome, the causative gene mutation for familial Mediterranean fever was detected.448 Hence, the pathogenesis for these conditions may be similar.

Leukotactic mechanisms, dermal dendrocytes, circulating autoantibodies, immune complexes, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) serotypes, and cytokines have all been postulated to contribute to the pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome. Complement does not appear to be essential to the disease process. In some patients antibodies to neutrophilic cytoplasmic antigens (ANCAS) have been demonstrated;430 however, these are likely to represent an epiphenomenon.2

Cytokines—directly and/or indirectly—may have an etiologic role in the development of Sweet syndrome symptoms and lesions.2,21–23 Elevated serum levels of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor and interleukin-6 were detected in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome-associated Sweet syndrome who was not receiving a drug.128 Detectable levels of intra-articular synovial fluid granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor has also been observed in an infant with classical Sweet syndrome.44 Another study demonstrated that the serum G-CSF level was significantly higher in individuals with active Sweet syndrome than in dermatosis patients with inactive Sweet syndrome.129 And, a recent study showed that the level of endogenous G-CSF was closely associated with Sweet syndrome disease activity in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia-associated Sweet syndrome and neutrophilic panniculitis.461

Significantly elevated levels of helper T-cell type 1 cytokines (interleukin-2 and interferon-γ) and normal levels of a helper T-cell type 2 cytokine (interleukin-4) have been seen in the sera of Sweet syndrome patients.130 In a patient with neuro-Sweet disease presenting with recurrent encephalomeningitis, serial measurements of cerebral spinal fluid interleukin-6, interferon-γ, interleukin-8, and IP10 [which is also referred to as the chemokine (C–X–C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10)] were elevated as compared to levels in control subjects with neurologic disorders and also correlated with total cerebral spinal fluid cell counts; this data suggests an important role of the helper T-cell type 1 cell (whose cytokines include interferon-γ and IP10) and interleukin-8 (a specific neutrophil chemoattractant) in the pathogenesis of neuro-Sweet disease.478 Other studies showed decreased epidermal staining for interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 and postulated that this was due to the release of these cytokines into the dermis.131 In summary, G-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor, interferon-γ, interleukin-1, interleukin-3, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 are potential cytokine candidates in the pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome.2,13,21–23,44,128–132

Clinical Findings

Sweet syndrome patients may appear dramatically ill. The skin eruption is usually accompanied by fever and leukocytosis. However, the skin disease can follow the fever by several days to weeks or be concurrently present with the fever for the entire episode of the dermatosis. Arthralgia, general malaise, headache, and myalgia are other Sweet syndrome associated symptoms (Table 32-2).1,2,23

Clinical Form | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Characteristic | Classicala (%) | Hematologic Malignancya (%) | Solid Tumora (%) | Drug Inducedb (%) |

Epidemiology | ||||

• Women | 80 | 50 | 59 | 71 |

• Prior upper respiratory tract infection | 75–90 | 16 | 20 | 21 |

• Recurrencec | 30 | 69 | 41 | 67 |

Clinical symptoms | ||||

• Feverd | 80–90 | 88 | 79 | 100 |

• Musculoskeletal involvement | 12–56 | 26 | 34 | 21 |

• Ocular involvement | 17–72 | 7 | 15 | 21 |

Lesion location | ||||

• Upper extremities | 80 | 89 | 97 | 71 |

• Head and neck | 50 | 63 | 52 | 43 |

• Trunk and back | 30 | 42 | 33 | 50 |

• Lower extremities | Infrequent | 49 | 48 | 36 |

• Oral mucous membranes | 2 | 12 | 3 | 7 |

Laboratory findings | ||||

• Neutrophiliae | 80 | 47 | 60 | 38 |

• Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation ratef | 90 | 100 | 95 | 100 |

• Anemiag | Infrequent | 82 | 83 | 100 |

• Abnormal platelet counth | Infrequent | 68 | 50 | 50 |

• Abnormal renal functioni | 11–50 | 15 | 7 | 0 |

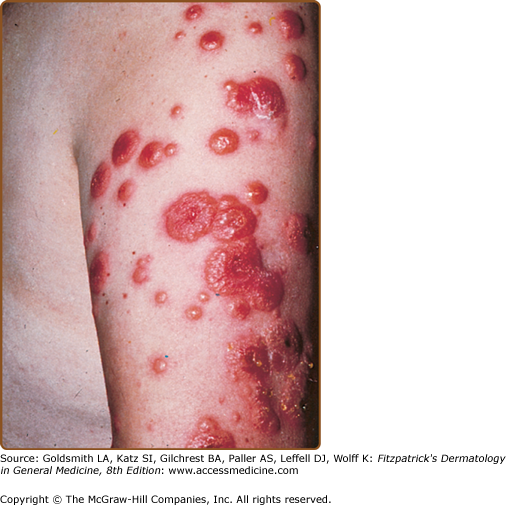

Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome typically appear as tender, red or purple–red, papules or nodules. The eruption may present as a single lesion or multiple lesions that are often distributed asymmetrically (Fig. 32-1). The pronounced edema in the upper dermis of the lesions results in their transparent, vesicle-like appearance and has been described as an “illusion of vesiculation” (Fig. 32-2). In later stages, central clearing may lead to annular or arcuate patterns. The lesions may appear bullous, become ulcerated, and/or mimic the morphologic features of pyoderma gangrenosum in patients with malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome.133,134 The lesions enlarge over a period of days to weeks. Subsequently, they may coalesce and form irregular sharply bordered plaques (Fig. 32-3). They usually resolve, spontaneously or after treatment, without scarring. Lesions associated with recurrent episodes of Sweet syndrome occur in one-third to two-thirds of patients.1,2,135,136

Figure 32-3

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Typical lesion consisting of coalescing, plaque-forming papules. A. Bright-red lesions on the neck. B. Lesion on the dorsum of the right-hand exhibiting the “relief of a mountain range” feature. (From Honigsmann H, Wolff K: Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome). In: Major Problems in Dermatology, vol 10, Vasculitis, edited by K Wolff, RK Winkelmann, consulting editor A Rook. London, Lloyd-Luke, 1980, p. 307, with permission.)

Cutaneous pathergy, also referred to as skin hypersensitivity, is a dermatosis-associated feature.1,2 It occurs when Sweet syndrome skin lesions appear at sites of cutaneous trauma.458,496 These include the locations where procedures have been performed such as biopsies,20 injection sites,431 intravenous catheter placement,20 and venipuncture.12,17,20,37,137,138 They also include sites of insect bites and cat scratches,20 areas that have received radiation therapy,139–141,138,484 and places that have been contacted by sensitizing antigens.137,142,420 In addition, in some Sweet syndrome patients, lesions have been photodistributed or localized to the site of a prior phototoxic reaction (sunburn).13,20,98,143–145 Sweet syndrome lesions have also rarely been located on the arm affected by postmastectomy lymphedema.100,146,419,505

Sweet syndrome can present as a pustular dermatosis.147 The lesions appear as tiny pustules on the tops of the red papules or eythematous-based pustules. Some of the patients previously described as having the “pustular eruption of ulcerative colitis” are perhaps more appropriately included in this clinical variant of Sweet syndrome.1,148

“Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands” or “pustular vasculitis of the dorsal hands” refers to a localized, pustular variant of Sweet syndrome when the clinical lesions are predominantly restricted to the dorsal aspect of the hands.3,149–154 The lesions from this latter group of individuals are similar to those of Sweet syndrome in morphology and rapid resolution after systemic corticosteroids and/or dapsone therapy was initiated. In addition, many of the individuals with this form of the disease also had concurrent lesions that were located on their oral mucosa, arm, leg, back, and/or face.3,155–163,425,435,440,442,457,462,470,495,497

The cutaneous lesions of subcutaneous Sweet syndrome usually present as erythematous, tender dermal nodules on the extremities.4,8,12,17,99,119,164–185 When the lesions are located on the legs, they often mimic erythema nodosum.170 Since Sweet syndrome can present concurrently21,125,187–189 or sequentially170 with erythema nodosum,17,21,187,190,509 tissue evaluation of one or more new dermal nodules may be necessary to establish the correct diagnosis—even in a patient whose Sweet syndrome has previously been biopsy-confirmed.1,2,4

(ch32etb2.1.) Extracutaneous manifestations of Sweet syndrome may include the bones, central nervous system, ears, eyes, kidneys, intestines, liver, heart, lung, mouth, muscles, and spleen.12,16,17,20,25,26,32,33,44,73,75,101,117,138,139,165,202,203,205,212–257,407,408,410,433,444,450,452,459,465,468,475,478,481,486,509 The incidence of ocular involvement (such as conjunctivitis) is variable in classical Sweet syndrome and uncommon in the malignancy-associated and drug-induced forms of the dermatosis; however, it may be the presenting feature of the condition. Mucosal ulcers of the mouth occur more frequently in Sweet syndrome patients with hematologic disorders and are uncommon in patients with classical Sweet syndrome23,26,102,117,203,252; similar to extracutaneous manifestations of Sweet syndrome occurring at other sites, the oral lesions typically resolve after initiation of treatment with systemic corticosteroids.1,2 In children, dermatosis-related sterile osteomyelitis has been reported.

Bone: acute sterile arthritis, arthralgias, focal aseptic osteitis, pigmented villonodular synovitis, sterile osteomyelitis (chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis).12,32,44,164,212–215 |

Central nervous system: acute benign encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, brain SPECT abnormalities, brain stem lesions, cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities, computerized axial tomography abnormalities, electroencephalogram abnormalities, encephalitis, Guillain–Barre syndrome, idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis, idiopathic progressive bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, leukoencephalopathy, magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities, neurologic symptoms, “neuro-Sweet disease,” pareses of central origin, polyneuropathy, psychiatric symptoms.33,68,212–229,410,450,478,486 |

Ears: tender red nodules and pustules that coalesced to form plaques in the external auditory canal and the tympanic membrane.230 |

Eyes: blepharitis, chemosis, conjunctival erythematous lesions with tissue biopsy showing neutrophilic inflammation, conjunctival hemorrhage, conjunctivitis, dacryoadenitis, episcleritis, glaucoma, iriidocyclitis, iritis, limbal nodules, ocular congestion, periocular swelling, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, retinal vasculitis, scleritis, uveitis.12,20,26,101,185,202,214,229,231–239,408,444,452,459,465,481 |

Kidneys: mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis, urinalysis abnormalities (hematuria and proteinuria).16,17,25,26,73 |

Intestines: intestine with extensive and diffuse neutrophilic inflammation, neutrophilic ileal infiltrate, pancolitis (culture-negative).36,203,240,241 |

Liver: hepatic portal triad with neutrophilic inflammation, hepatic serum enzyme abnormalities, hepatomegaly.12,16,17,20,25,26,212,224,242 |

Heart: aortic stenosis (segmental), aortitis (neutrophilic and segmental), cardiomegaly, coronary artery occlusion, heart failure, myocardial infiltration by neutrophils, vascular (aorta, bracheocephalic trunk and coronary arteries) dilatation.243–247 |

Lung: bronchi (main stem) with red-bordered pustules, bronchi with neutrophilic inflammation, pleural effusion showing abundant neutrophils without microorganisms, chest roentgenogram abnormalities: corticosteroid-responsive culture-negative infiltratives, pulmonary tissue with neutrophilic inflammation.17,20,73,101,138,139,165,205,212,246–251,433,468,475,139 |

Mouth: aphthous-like superficial lesions (buccal mucosa, tongue), bullae and vesicles (hemorrhagic: labial and gingival mucosa), gingival hyperplasia, necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, nodules (necrotic: labial mucosa), papules (macerated: palate and tongue), pustules (individual and grouped: palate and pharynx), swelling (tongue), ulcers (buccal mucosa and palate).26,75,102,117,203,249,252–254 |

Muscles: magnetic resonance imaging (T1-weighted and T2-weighted) abnormalities: high signal intensities due to myositis and fasciitis, myalgias (in up to half of the patients with idiopathic Sweet’s syndrome), myositis (neutrophilic), tendinitis, tenosynovitis.73,75,244,255–257 |

(eTable 32-2.2.) Several conditions have been observed to occur either before, concurrent with, or following the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Therefore, the development of Sweet syndrome may be etiologically related to Behcet’s disease, cancer, erythema nodosum, infections, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, relapsing polychondritis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and thyroid disease. The association between Sweet syndrome and the other conditions (eTable 32-2.2) remains to be established.1,2,5,11–20,30,36–43,69–126, 158–161,164,166,186–190,195,214,231,236,259–339, 400,402,406,410,411,415,417,418,421–424,426–429,434,436–442,445,446,448,449,452–456,459, 460,463,464,466–469,471–477,479,480,482,483,487–490, 492–494,496,497,500,502–504,508,509

Probably Bona Fide Associated Conditions

|

Possibly Bona Fide Associated Conditions

|

Validity of Associated Conditions Remains to be Established

|

An inflammatory infiltrate of mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes is the unifying characteristic of neutrophilic dermatoses of the skin and mucosa. Concurrent or sequential occurrence of Sweet syndrome with either erythema elevatum diutinum,340 neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis,6 pyoderma gangrenosum,9,231,269,341,342,430,483,497 subcorneal pustular dermatosis,6,9 and/or vasculitis3,192,231 has been observed. Although these conditions can display similar clinical and pathologic features, the location of the neutrophilic infiltrate helps to differentiate them.6,120,499

In patients with hematologic disorders, Sweet syndrome may present as a paraneoplastic syndrome (signaling the initial discovery of an unsuspected malignancy), a drug-induced dermatosis (following treatment with either all-trans–retinoic acid, bortezomib, G-CSF, or imatinib mesylate), or a condition whose skin lesions concurrently demonstrate leukemia cutis.1 Acute leukemia (myelocytic and promyelocytic) is the most frequent hematologic dyscrasia associated with leukemia cutis (characterized by abnormal neutrophils) and Sweet syndrome (consisting of mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes) being present in the same skin lesion.1,70,71,93,109,165,205–211,497 Myelodysplastic syndrome and myelogenous leukemia (either chronic or not otherwise specified) are the other associated hematologic disorders that have been associated with concurrent Sweet syndrome and leukemia cutis.109

“Secondary” leukemia cutis, in which the circulating immature myeloid precursor cells are innocent bystanders that have been recruited to the skin as the result of an inflammatory oncotactic phenomenon stimulated by the Sweet syndrome lesions has been suggested as one of the hypotheses to explain concurrent Sweet syndrome and leukemia cutis in the same lesion.165,206,207 Alternatively, “primary” leukemia cutis, in which the leukemic cells within the skin constitutes the bonified incipient presence of a specific leukemic infiltrate is another possibility.207 Finally, it is possible that the atypical cells of leukemia cutis developed into mature neutrophils of Sweet syndrome as a result of G-CSF therapy-induced differentiation of the sequestered leukemia cells in patients with “primary” leukemia cutis who were being treated with this agent.205

Laboratory Tests

Evaluation of a lesional skin biopsy is helpful when the diagnosis of Sweet syndrome is suspected. Lesional tissue should also be submitted for bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and possibly viral cultures since the pathologic findings of Sweet syndrome are similar to those observed in cutaneous lesions caused by infectious agents.1,2

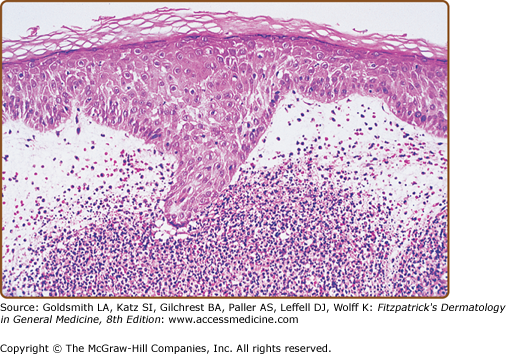

A diffuse infiltrate of mature neutrophils is characteristically present in the papillary and upper reticular dermis (Fig. 32-4); however, it can also involve the epidermis or adipose tissue. “Histiocytoid” Sweet syndrome refers to the setting in which the hematoxylin and eosin-stained infiltrate of immature myeloid cells are “histiocytoid-appearing” and are therefore initially misinterpreted as histiocytes.201,412–414,436,443,445,460,474

Figure 32-4

Histopathologic presentation of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome) demonstrates massive edema of the papillary dermis and a dense diffuse infiltrate of mature neutrophils throughout the upper dermis (hematoxylin and eosin stain). (From Cohen PR et al: Sweet’s syndrome in patients with solid tumors. Cancer 72:2723-2731, 1993, with permission.)

The dermal inflammation is usually dense and diffuse; however, it can also be perivascular or demonstrate “secondary” changes of leukocytoclastic vasculitis believed to be occurring as an epiphenomenon and not representative of a “primary” vasculitis,3,192,193 Neutrophilic spongiotic vesicles194 or subcorneal pustules12,80,167,195,196 result from exocytosis of neutrophils into the epidermis.12,17,80,167,194,195,197 When the neutrophils are located either entirely or only partially in the subcutaneous fat, the condition is referred to as “subcutaneous Sweet syndrome”.4,8,12,17,99,119,164–184,451,461,493,497

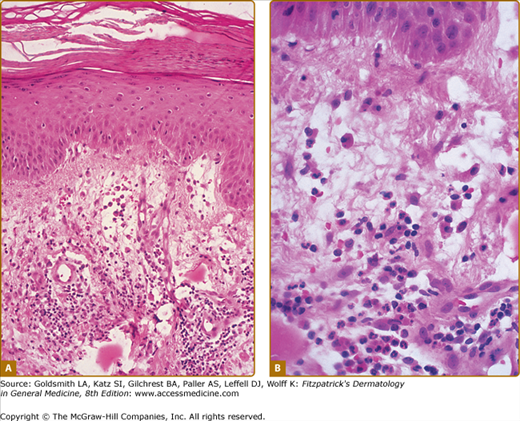

Edema in the dermis, swollen endothelial cells, dilated small blood vessels, and fragmented neutrophil nuclei (referred to as karyorrhexis or leukocytoclasia) may also be present (Fig. 32-5). Fibrin deposition or neutrophils within the vessel walls (changes of “primary” leukocytoclastic vasculitis) are usually absent and the overlying epidermis is normal.1,2,23,167,168 However, the spectrum of pathologic changes described in cutaneous lesions of Sweet syndrome has expanded to include concurrent leukemia cutis, vasculitis, and variability of the composition or the location of the inflammatory infiltrate.3,191,491,496

Figure 32-5

Characteristic histopathologic features of Sweet syndrome are observed at low (A) and high (B) magnification: papillary dermal edema, swollen endothelial cells, and a diffuse infiltrate of predominantly neutrophils with leukocytoclasia, yet no evidence of vasculitis (hematoxylin and eosin stain). (From Cohen PR et al: Concurrent Sweet’s syndrome and erythema nodosum: A report, world literature review and mechanism of pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 19:814-820, 1992, with permission.)

Lymphocytes or histiocytes may be present in the inflammatory infiltrate of Sweet syndrome lesions.11,104,167,168,198–200,504 Eosinophils have also been noted in the cutaneous lesions from some patients with either idiopathic11,167,168,195,202–204,212 or drug-induced84,107,110,111 Sweet syndrome. Abnormal neutrophils (leukemia cutis)—in addition to mature neutrophils—comprise the dermal infiltrate in occasional Sweet syndrome patients with hematologic disorders.1,70,71,93,109,165,205–211

Pathologic findings of Sweet syndrome can also occur in extracutaneous sites. Often, these present as sterile neutrophilic inflammation in the involved organ. These changes have been described in the bones, intestines, liver, aorta, lungs, and muscles of patients with Sweet syndrome.2

Peripheral leukocytosis with neutrophilia and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and are the most consistent laboratory findings in Sweet syndrome.23 However, leukocytosis is not always present in patients with biopsy-confirmed Sweet syndrome.26 For example, anemia, neutropenia, and/or abnormal platelet counts may be observed in some of the patients with malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome. Therefore, a complete blood cell count with leukocyte differential and platelet count, evaluation of acute phase reactants (such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein), serum chemistries (evaluating hepatic function and renal function), and a urinalysis should be performed. It is also reasonable to perform a serologic evaluation of thyroid function since there appears to be a strong association between thyroid disease and Sweet syndrome.1,2

Extracutaneous manifestations of Sweet syndrome may result in other laboratory abnormalities. Patients with central nervous system involvement may have abnormalities on brain SPECTs (single photon emission computed tomography), computerized axial tomography, electroencephalograms, magnetic resonance imaging, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Patients with kidney and liver involvement may demonstrate urinalysis abnormalities (hematuria and proteinuria) and hepatic serum enzyme elevation. And, patients with pulmonary involvement may have pleural effusions and corticosteroid-responsive culture-negative infiltrates on their chest roentgenograms.2,343

Recommendations for the initial malignancy workup in newly diagnosed Sweet syndrome patients without a prior cancer were proposed by Cohen and Kurzrock in 1993.15 Their recommendations were based upon the age-related recommendations of the American Cancer Society for early detection of cancer in asymptomatic persons and the neoplasms that had concurrently been present or subsequently developed in previously cancer-free Sweet syndrome patients. The recommended evaluation included the following:

A detailed medical history

A complete physical examination, including:

examination of the thyroid, lymph nodes, oral cavity, and skin;

digital rectal examination;

breast, ovary, and pelvic examination in women; and

prostate and testicle examination in men.

Laboratory evaluation:

carcinoembryonic antigen level;

complete blood cell count with leukocyte differential and platelet count;

pap test in women;

serum chemistries;

stool guaiac slide test;

urinalysis; and

urine culture.

Other screening tests:

chest roentgenograms;

endometrial tissue sampling in either menopausal women or women with a history of abnormal uterine bleeding, estrogen therapy, failure to ovulate, infertility, or obesity; and

sigmoidoscopy in patients over 50 years of age.

Since the initial appearance of dermatosis-related skin lesions had been reported to precede the diagnosis of a Sweet syndrome-associated hematologic malignancy by as long as 11 years, they also suggested that it was reasonable to check a complete blood cell count with leukocyte differential and platelet count every 6–12 months.2,15

Differential Diagnosis

Sweet syndrome skin and mucosal lesions mimic those of other conditions (Table 32-3.)2,15,23,148,165,202,220,344,345,409,421,448,498 Therefore, infectious and inflammatory disorders, neoplastic conditions, reactive erythemas, vasculitis, other cutaneous conditions, and other systemic diseases are included in the clinical differential diagnosis of Sweet syndrome.

Most Likely Drug eruptions Cellulitis Chloroma Erysipelas Erythema nodosum Leukemia cutis Leukocytoclastic vasculitis Panniculitis Pyoderma gangrenosum |

Consider Acral erythema Erythema elevatum diutinum Erythema multiforme Halogenoderma Lymphoma Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis Periarteritis nodosa Urticaria Viral exanthem |

Always Rule Out Bacterial sepsis Behcet’s disease Bowel bypass syndrome Dermatomyositis Familial Mediterranean fever Granuloma faciale Leprosy Lupus erythematosus Lymphangitis Metastatic tumor Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis Rosacea fulminans Schnitzler’s syndrome Syphilis Systemic mycosis Thrombophlebitis Tuberculosis |

The histologic differential diagnosis of Sweet syndrome includes conditions microscopically characterized by either neutrophilic dermatosis or neutrophilic panniculitis (ch32etb3.1).2–4,6,12,193,346–353,432,451 The pathologic changes associated with Sweet syndrome are similar to those observed in an abscess or cellulitis; therefore, culture of lesional tissue for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria should be considered to rule out infection.23 Leukemia cutis not only mimics the dermal changes of Sweet syndrome, but can potentially occur within the same skin lesion as Sweet syndrome; however, in contrast to the mature polymorphonuclear neutrophils found in Sweet syndrome, the dermal infiltrate in leukemia cutis consists of malignant immature leukocytes.354 The pathologic changes in the adipose tissue of subcutaneous Sweet syndrome lesions can be found in either the lobules, the septae, or both; therefore, conditions characterized by a neutrophilic lobular panniculitis also need to always be considered and ruled out.2,4

Most Likely Abscess/cellulitis: positive culture for infectious agent Leukemia cutis: dermal infiltrate consists of immature neutrophils Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: vessel wall destruction—extravasated erythrocytes, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, karyorrhexis, and neutrophils in the vessel wall Pyoderma gangrenosum: ulcer with overhanging, undermined violaceous edges |

Consider Erythema elevatum diutinum: erythematous asymptomatic plaques often located on the dorsal hands and elbows; younger lesions have microscopic features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, whereas older lesions have dermal fibrosis and mucin Granuloma faciale: yellow to red to brown indurated asymptomatic facial plaques; there is a grenz zone of normal papillary dermis beneath which there is a dense diffuse inflammatory infiltrate of predominantly neutrophils (with microscopic features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis) and numerous eosinophils Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis: neutrophils around eccrine glands, often in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia receiving induction chemotherapy |

Always Rule Out Bowel (intestinal) bypass syndrome: history of jejunal–ileal bypass surgery for morbid obesity Halogenoderma: neutrophilic dermal infiltrate with necrosis and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal abscesses; history of ingestion of bromides (leg lesions), iodides (facial lesions), or topical fluoride gel to teeth during tumor radiation therapy to face Lobular neutrophilic panniculitides: in addition to subcutaneous Sweet’s syndrome, these include α 1-antitrypsin deficiency syndrome, factitial panniculitis (secondary to the presence of iatrogenic or self-induced foreign bodies), infectious panniculitis (secondary to either a bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, or protozoan organism), pancreatic panniculitis, rheumatoid arthritis-associated panniculitis Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis: an urticarial eruption demonstrating perivascular and interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate with intense leukocytoclasia but without vasculitis and without dermal edema and often associated with a systemic disease: Schnitzler’s syndrome, adult-onset Still disease, lupus erythematosus, and the hereditary autoinflammatory fever syndromes Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis: history of rheumatoid arthritis, nodules, and plaques |

Complications

Complications in patients with Sweet syndrome can be directly related to the mucocutaneous lesions or indirectly related to the Sweet syndrome-associated conditions. Skin lesions may become secondarily infected and antimicrobial therapy may be necessary. In patients with malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, reappearance of the dermatosis may herald the unsuspected discovery that the cancer has recurred. Systemic manifestations of Sweet syndrome-related conditions—such as inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis and thyroid diseases—may warrant disease-specific treatment.

Prognosis and Clinical Course

The symptoms and lesions of Sweet syndrome eventually resolved without any therapeutic intervention in some patients with classical Sweet syndrome. However, the lesions may persist for weeks to months.10,23,254,355 In patients with malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, successful management of the cancer occasionally results in clearing of the related dermatosis.13,15,23 Similarly, discontinuation of the associated medication in patients with drug-induced Sweet syndrome is typically followed by spontaneous improvement and subsequent resolution of the syndrome.13,15,23 Surgical intervention has also resulted in the resolution of Sweet syndrome in some of the patients who had associated tonsillitis, solid tumors, or renal failure.1,2,19,315,356,357,507

Sweet syndrome may recur following either spontaneous remission or therapy-induced clinical resolution.10 The duration of remission between recurrent episodes of the dermatosis is variable. Sweet syndrome recurrences are more common in cancer patients; in this patient population, the reappearance of dermatosis-associated symptoms and lesions may represent a paraneoplastic syndrome that is signaling the return of the previously treated malignancy.1,2,15,135

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree