62. Body Contouring in Massive-Weight-Loss Patients

Classification of Morbid Obesity

1 , 2 (Table 62-1)

Obesity: Body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2

Severe obesity: BMI >35 kg/m2

Morbid obesity: BMI >40 kg/m2. Morbidly obese patients exceed their ideal body weight (IBW) by >100 pounds or are >100% their IBW.

Super obesity: BMI >50 kg/m2. These patients exceed their IBW by >225%.

BMI (kg/m2) | Obesity Class | |

Underweight | <18.5 | |

Normal | 18.6-24.9 | |

Overweight | 25.0-29.9 | |

Obese | 30.1-34.9 | I |

Severely obese | 35.0-39-9 | II |

Extremely obese | 40.0+ | III |

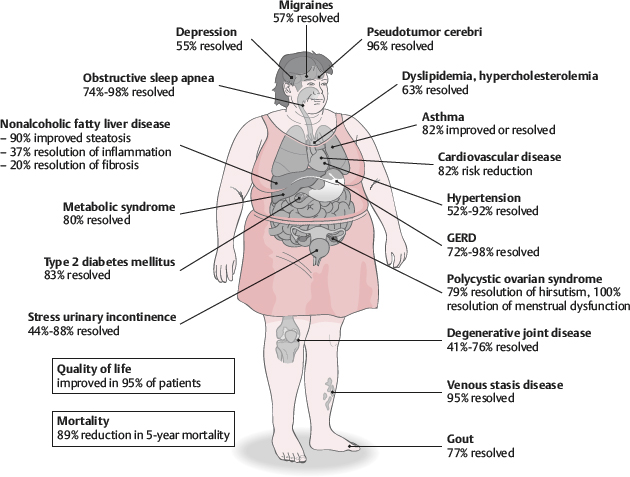

Comorbidities of Morbid Obesity

Osteoarthritis

Obstructive sleep apnea

Gastroesophageal reflux

Lipid abnormalities

Hypertension

Diabetes mellitus

Congestive heart failure

Asthma

Senior Author Tip:

Following massive weight loss (MWL), 70% of patients experience a significant reduction in self-image due to the deflated nature of their tissues.

Complications of Skin Redundancy

Intertriginous infections/rashes

Musculoskeletal pain

Functional impairment, especially with ambulation, urination, and sexual activity

Psychological issues such as depression and low self-esteem

Bariatric Surgery Techniques

Performed through traditional open techniques or laparoscopic techniques. Laparoscopic techniques substantially reduce the morbidity from postoperative wound infections, dehiscence, and incisional hernias.

Restrictive Procedures

Manipulate the stomach only

Reduce caloric intake by decreasing the quantity of food consumed at a single meal

Vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG): Not very effective, because >50% of patients unable to maintain weight loss

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (lap band): Achieves approximately 50% reduction of excess weight

Gastric sleeve

Gastric tube created by resecting greater curvature of stomach

70% remission of type 2 diabetes, which is less than with gastric bypass 3

Mean excess weight loss 50% at 6 years 3

Orbera weight loss balloon (Apollo Endosurgery)

Fluid-filled intragastric balloon to decrease gastric capacity

Combination Restrictive and Malabsorptive Procedures

Superior for weight reduction and decreases in comorbidities (Fig. 62-1)

The malabsorptive component limits the absorption of nutrients and calories from ingested foods by bypassing the duodenum and other specific lengths of the small intestine.

Biliopancreatic diversion (BPD): Achieves nearly 75%-80% reduction of excess weight, produces significant nutritional deficiencies

BPD with duodenal switch: Approximately 73% of excess weight loss

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB): This is the most common bariatric procedure performed and is considered the benchmark. It achieves excess weight loss >50%. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies present in 30%-40% of patients.

Senior Author Tip:

Space-occupying balloons are becoming more popular in the United States and worldwide. They have been shown to be effective for achieving weight loss, particularly for the low and moderate BMI patients. Laparoscopic adjustable bands are losing popularity because of subsequent weight gain that is frequently seen.

Fundamentals of Body Contouring after Massive Weight Loss

Liposuction

Not effective as a sole modality in massive-weight-loss patients

Can be used in areas of mild contour irregularities as an adjunct to excision procedures

Can be performed after recovery from major excisional procedures for refinement of contour

Can be performed at the excision or as a staged surgery. Table 62-2 presents the pros and cons of liposuction in massive-weight-loss patients. 6

Timing of Body Contouring after Bariatric Surgery

Delay surgery until the patient’s weight has stabilized for at least 6 months. This corresponds to ~12-18 months after gastric bypass.

Reasons to delay surgery until stable weight achieved:

Patients have time to achieve metabolic and nutritional homeostasis.

The period of rapid weight loss is detrimental to wound healing.

The risk of surgical complications decreases significantly from around 80% to 33% when patients approach their IBW.

Aesthetic outcomes are better for patients near their IBW.

Most patients will settle at a BMI of 30-35 kg/m2 after bariatric surgery.

Consider motivated patients in this category for an initial panniculectomy or breast reduction to improve comfort during exercise.

This may facilitate lifestyle changes that will result in further weight loss and provide better aesthetic outcomes with subsequent surgery.

The best candidates for extensive body contouring after massive weight loss will have a BMI of 25-30 kg/m2.

Senior Author Tip:

Massive-weight-loss patients can be considered either “complete” or “incomplete,” based on residual subcutaneous fat. Most massive-weight-loss patients fall in the “incomplete” category, requiring reduction of subcutaneous tissue in addition to skin resection.

Preoperative Evaluation

Record greatest and presenting BMI.

Assess stability of medical comorbidities and psychiatric problems.

40% of bariatric patients are treated for psychiatric diagnoses.

Determine smoking history.

Common nutritional deficiencies

Iron deficiency anemia

Vitamin B12

Calcium

Potassium

Zinc

Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K)

Protein deficiencies

Preoperative laboratory tests should include complete blood cell count (CBC), electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, uric acid, liver function tests, glucose, calcium, ferritin, total protein, albumin/prealbumin, B12/folate, prothrombin/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT), fat-soluble vitamins.

Senior Author Tip:

“Complete” weight-loss patients are more likely to have had a significant bypass procedure resulting in anemia, protein, and other deficiencies. Preoperative evaluation and treatment is imperative for proper wound healing.

Surgical Strategy

The goals of surgery are to alleviate the functional, aesthetic, and psychological impairments from skin redundancy.

Determine the priorities of the patient. However, general sequence should be:

Trunk, abdomen, buttocks, lower thighs

Upper thorax/breasts, arms

Medial thighs

Facial rejuvenation

Staging Considerations

Body contouring surgery in patients requiring several areas of correction is multistaged to best minimize complications, pain, and need for blood transfusions.

Solo surgeon versus team approach

The team approach can accomplish more in one stage.

Patient safety is paramount.

Longer operative times will increase likelihood of morbidities (e.g., hypothermia, anemia, thromboembolism, and wound complications).

Design operating times that are patient-, surgeon-, and practice-specific.

The greater the drop in BMI, usually the greater the deflation.

Generally, more resection can be accomplished at one time with greater deflation or lower BMI.

Determine patient’s ability to tolerate long procedures.

Evaluate patient’s assistance at home for recovery process.

Patients should be back to their preoperative health status before returning to the operating room. Recovery of at least 3 months is usually required before performing additional stages.

Senior Author Tip:

A sequence of three procedures is usually required to complete body contouring following massive weight loss. This can often require 1 year or more.

Physical Examination

Assess body habitus of patient.

Evaluate regional fat deposition.

Evaluate laxity of the skin envelope.

Evaluate quality of skin-fat envelope, which depends on degree of deflation.

Estimate extent of tissue resection using a pinch test.

Assess “translation of pull,” which is the extent that distant tissue is affected with region of resection.

Evaluate for old scars.

Anticipate location of scars and expect scar migration.

Tissue Characteristics and Surgical Techniques

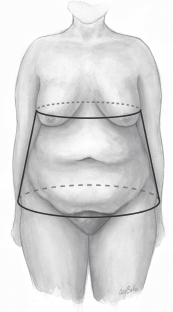

Trunk/Abdomen

The abdomen usually has the greatest deformity in massive-weight-loss patients.

Most tissue descent is seen along the lateral axillary lines.

The truncal tissues take on an appearance of an inverted cone (Fig. 62-2).

The mons pubis will have varying degree of ptosis.

Surgical goals

Flatten contour.

Tighten abdominal wall with fascial plication.

Repair ventral hernia, if present.

Elevate the mons pubis.

Preoperative Evaluation of the Trunk/Abdomen

Identify locations of old scars on the abdomen.

Determine the extent of the panniculus and descent of abdomen onto lateral thighs.

Identify any presence of hernias.

Assess extent of mons ptosis.

Assess for presence/extent of midback or lower back rolls.

Assess for buttock ptosis and contour. Determine if patient may benefit from buttock autoaugmentation.

Surgical Approach to the Trunk/Abdomen

Traditional abdominoplasty techniques fail to maximally improve body contour in this patient population, because they do not address the lateral tissue laxity.

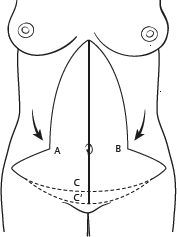

Fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty (Fig. 62-3) can be performed for patients without back and lateral thigh ptosis.

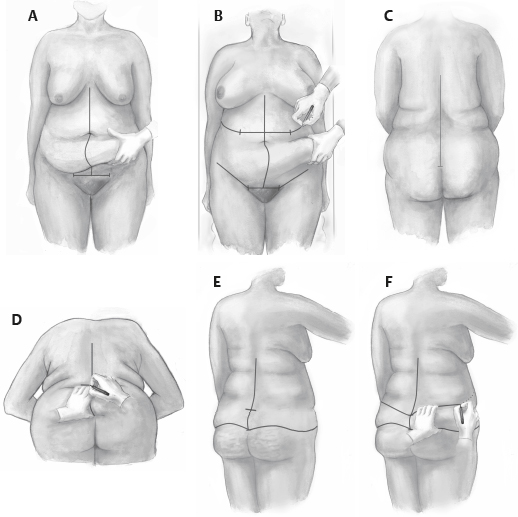

Circumferential belt lipectomy/lower body lift (Fig. 62-4) addresses the circumferential nature of the tissue ptosis seen in the trunk. 7

Allows resection of the entire lower section of the inverted-cone deformity

Allows elevation of the buttocks and lateral thighs to produce a comprehensive additional lower body lift

Patients with BMI >35 have higher risks for complications after belt lipectomy/lower body lift. 1

Key components of surgical technique

Mark patient as shown (see Fig. 62-4).

Start with the patient prone. Make superior incision first on back and dissect inferiorly.

The posterior resection should be taken down deep to the superficial fascia to maintain a layer of fat on the deep fascia. This will minimize seroma formation.

Perform liposuction on lateral thighs to release zones of adherence, which allows lateral thigh elevation.

Align final scars below pelvic rim (horizontal level across the superior aspect of iliac crests). This will keep scars hidden under most undergarments and bikinis.

Make inferior incision on the abdomen, similar to traditional abdominoplasty technique.

Perform an umbilicoplasty to shorten the umbilical stalk flush with the newly contoured abdominal skin, regardless of the contouring technique used.

Prevent excess tension on the mons, which can elevate the clitoris and urethral meatus.

Widely drain anteriorly and posteriorly to prevent seroma formation.

Tip:

Perform markings in the office on the day before surgery for patient comfort and to prevent time delays on day of surgery.

Mark the anterior/inferior incision at the level of the pubic bone, generally 4-7 cm above the introitus or base of the penis.

Minimize posterior skin resection to prevent competing anterior and posterior tension forces.

Be more aggressive with lateral and anterior resections, because these are most visible areas to the patient.

Contour the mons in two stages to prevent distortion of the clitoris and urethral meatus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree