Genetic and Acquired Bullous Diseases

Bullous diseases are defined as conditions where cavities filled with fluid form in the superficial layers of skin clinically manifesting as vesicles or blisters. Although vesicles and blisters can arise as secondary lesions in many conditions, in the bullous diseases they are the primary pathologic event. Genetic (hereditary) and acquired (mostly autoimmune) bullous diseases exist.

Classification

Based on level of cleavage and blister formation, there are three main types:

• Epidermolytic. Cleavage occurs in keratinocytes: EB simplex (EBS).

• Junctional. Cleavage occurs in basal lamina: junctional EB (JEB).

• Dermolytic. Cleavage occurs in most superficial papillary dermis: dermolytic or dystrophic EB (DEB).

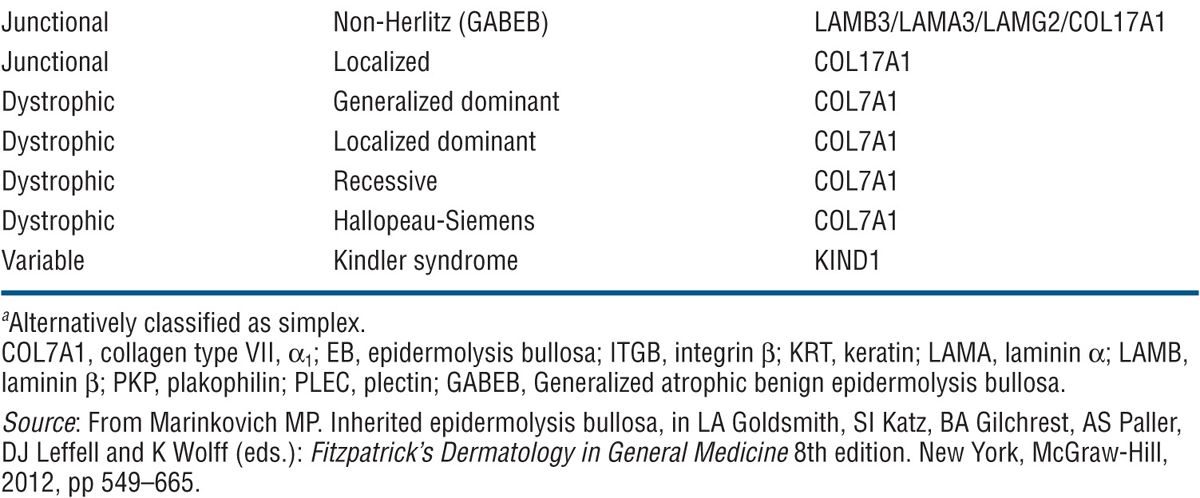

In each of these groups, there are several distinct types of EB based on clinical, genetic, histologic/electronmicroscopic, and biochemical evaluation (Table 6-1). Only the most important are discussed here.

TABLE 6-1 CLASSIFICATION OF EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA

Epidemiology

The overall incidence of hereditary EB is placed at 19.6 live births per 1 million births in the United States. Stratified by subtype, the incidences are 11 for EBS, 2 for JEB, and 5 for DEB. The estimated prevalence in the United States is 8.2 per million, but this figure represents only the most severe cases, as it does not include the majority of very mild disease going unreported.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

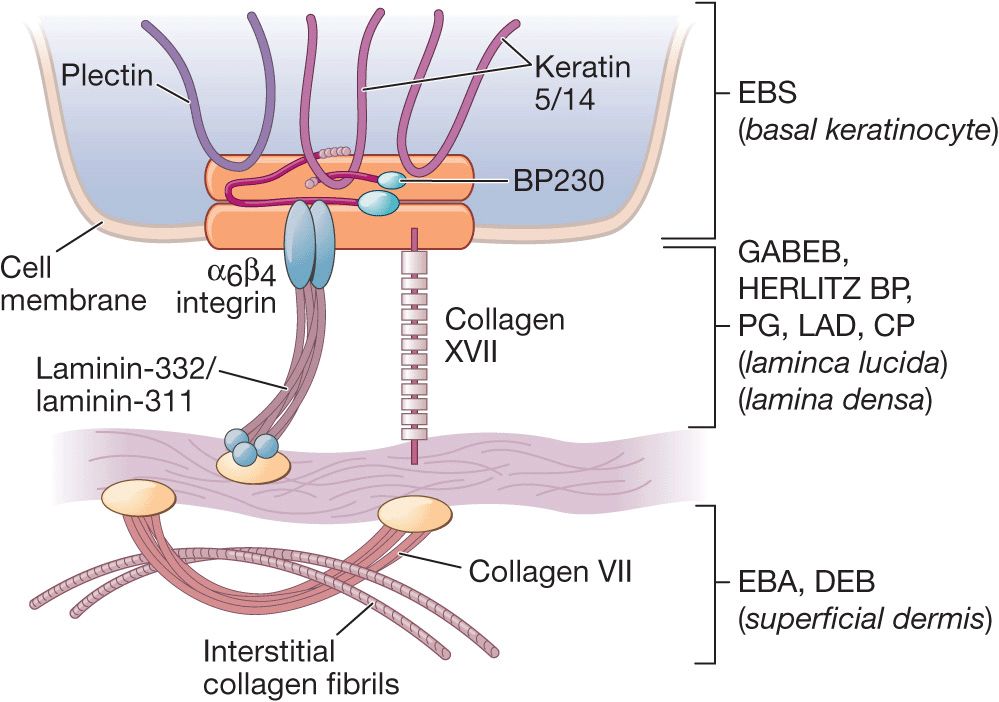

Genetic Defects. Molecules involved are listed in Table 6-1 and localization in the tissue and sites of cleavage are shown in (Fig. 6-1).

Figure 6-1. Schematic of the components of dermal-epidermal basement membrane (left panel) and levels of dermal-epidermal separation in hereditary and autoimmune bullous diseases with dermal-epidermal cleavage discussed in this Atlas. EBS, epidermolysis bullosa simplex; BP, bullous pemphigoid; PG, pempihgoid gestationis; LAD, linear IgA disease; CP, cicatricial pemphigoid; EBA, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita; DEB, dermolytic epidermolysis bullosa. Modified from Marinkowich MP. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa. [From Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, and Wolff K (eds.). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine 8th edition. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2012, p 649-665.]

Clinical Phenotypes

EB Simplex

A trauma-induced, intraepidermal blistering, based in most cases on mutations of the genes for keratins 5 and 14 resulting in a disturbance of the stability of the keratin filament network (Table 6-1). This causes cytolysis of basal keratinocytes and a cleft in the basal cell layer (Fig. 6-1). Different subgroups have considerable phenotypic variations (Table 6-1), and there are several distinct forms, most of which are dominantly inherited. The two most common are described below.

Generalized EBS (Table 6-1). The so-called Koebner variant is dominantly inherited, with onset at birth to early infancy. Generalized blistering following trauma with a predilection for traumatized body sites such as feet, hands, elbows, and knees. Blisters tense or flaccid (Fig. 6-2) leading to erosions. Rapid healing and only minimal scarring at sites of repeated blistering. Palmoplantar hyperkeratoses may be present. Nails, teeth, and oral mucosa are usually spared.

Figure 6-2. Generalized EBS (Koebner) This 4-year-old girl has had blistering since very early infancy with predilection for traumatized body sites such as palms and soles and also elbows and knees. Blistering also occurs in other areas such as the forearm, as shown here, and on the trunk. There is hardly any evidence of scarring.

Localized EBS. Weber-Cockayne subtype (Table 6-1). The most common form of EBS. Onset in childhood or later. The disease may not present itself until adulthood, when thick-walled blisters on the feet and hands occur after excessive exercise, manual work, or military training (Fig. 6-3). Increased ambient temperature facilitates lesions. Hyperhidrosis of palms and soles; secondary infection of blisters.

Figure 6-3. Localized EBS Thick-walled blisters on the soles. The disease presented itself for the first time during military training when this 19-year-old had to march over a long distance.

Junctional EB

All forms of JEB share the pathologic feature of blister formation within the lamina lucida of the basement membrane (Fig. 6-1). Mutations are in the gene for collagen XVII and laminin (Table 6-1). Autosomal recessive, several clinical phenotypes (Table 6-1), three of which are described below.

Herlitz EB (JEB Gravis). Mortality rate is 40% during the first year of life. Generalized blistering at birth (Fig. 6-4) or distinctive and severe periorificial granulation, loss of nails, and involvement of most mucosal surfaces. The skin of these children may be completely denuded, representing oozing painful erosion. Associated findings include all symptoms resulting from generalized epithelial blistering with respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary organ systems involved.

Figure 6-4. Junctional epidermolysis bul losa (Herlitz) There are large eroded, oozing, and bleeding areas that occurred intrapartum. When this newborn is lifted up, dislodgment of epidermis and erosions occur with manual handling.

Non-Herlitz EB JEB Mitis. These children may have moderate or severe JEB at birth but survive infancy and clinically improve with age. Periorificial nonhealing erosions during childhood.

Non-Herlitz EB Generalized Atrophic Benign Epider-molysis Bullosa (GABEB). Presents at birth with generalized cutaneous blistering and erosions on the extremities, trunk, face, and scalp. Survival to adulthood is the rule, but blistering on traumatized areas continues (Figs. 6-5 and 6-6). Pronounced with increased ambient temperature, and there is atrophic healing of the lesions. Nail dystrophy, nonscarring or scarring alopecia, mild oral mucous membrane involvement, and enamel defects may occur. Mutations are in the genes for laminin and collagen XVII (Table 6-1).

Figure 6-5. Generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa (GABEB) This 19-year-old man has had cutaneous blistering since birth, with blisters and erosions arising on the elbows and knees and also on the trunk and arms following trauma. There is no scarring but some spotty atrophy.

Figure 6-6. Generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa (GABEB) This 20-year-old man has had generalized cutaneous blistering since birth. Note: A large erosion on the left lower back and hemorrhagic crusts on the lower arms. Erythema on the back indicates sites of previous blistering.

Dystrophie EpidermOlySiS BullOSa (DEB)

DEB is a spectrum of dermolytic diseases where blistering occurs below the basal lamina (Fig. 6-1); healing is therefore usually accompanied by scarring and milia formation—hence, the name dystrophic. There are four principal subtypes, all due to mutations in anchoring fibril VII collagen (Table 6-1), two of which are described below.

Dominant DEB. Cockayne-Touraine disease. Onset in infancy or early childhood with acral blistering and nail dystrophy; milia and scar formation, which may be hypertrophic or hyperplastic. Oral lesions are uncommon, and teeth are usually normal.

Recessive DEB (RDEB). It comprises a larger spectrum of clinical phenotypes. The localized, less severe form (RDEB mitis) occurs at birth, shows acral blistering, atrophic scarring, and little or no mucosal involvement. Generalized, severe RDEB, the Hallopeau-Siemens variant, is mutilating. There is generalized blistering at birth, and progression and repeated blistering at the same sites (Fig. 6-7) result in remarkable scarring and ulcerations, syndactyly with loss of nails (Fig. 6-8) and even mitten-like deformities of hands and feet, and flexion contractures. There are enamel defects with caries and parodontitis, strictures and scarring in the oral mucous membrane and esophagus, urethral and anal stenosis, and ocular surface scarring; also malnutrition, growth retardation, and anemia. Squamous cell carcinoma in chronic recurrent erosions.

Figure 6-7. Generalized recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) In this severe disease, blistering occurs often at the same sites, as in this 10-year-old girl. Blisters lead to erosions and these become ulcers that have a low tendency to heal. When healing occurs, it results in scarring. This girl also has enamel defects with caries, strictures of the esophagus, severe anemia, and considerable growth retardation. It is obvious that the large wounds are portal entries for systemic infection.

Figure 6-8. Generalized recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) Loss of all fingernails, syndactyly, and severe atrophic scarring on the dorsa of hands.

Diagnosis

Based on clinical appearance and history. Histopathology determines the level of cleavage, which is further defined by electron microscopy and/or immunohistochemical mapping. Western blot, Northern blot, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, and DNA sequences may then identify the mutated gene.

Management

There is as yet no causal therapy for EB, but gene therapy is being investigated. Management is tailored to the severity and extent of skin involvement: supportive skin care, supportive care for other organ systems, and systemic therapies for complications. Wound management, nutritional support, and infection control are key.

In EBS, maintenance of a cool environment and use of soft, well-ventilated shoes are important. Blistered skin is treated by saline compresses and topical antibiotics or, in the case of inflammation, with topical steroids. More severely affected JEB and DEB patients are treated like patients in a burn unit. Gentle bathing and cleansing are followed by protective emollients and nonadherent dressings.

Although rare, EB and, in particular, JEB and DEB pose a major health and socioeconomic problem. Organizations such as the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DEBRA) offer assistance that includes patient education and support.

Classification (See Table 6-2)

TABLE 6-2 CLASSIFICATION OF PEMPHIGUS

Epidemiology

PV: Rare, more common in Jews and people of Mediterranean descent. In Jerusalem the incidence is estimated at 16 per million, whereas in France and Germany it is 1.3 per million.

PF: Also rare but endemic in rural areas in Brazil (fogo selvagem), where the prevalence can be as high as 3.4%.

Age of Onset. 40-60 years; fogo selvagem also in children and young adults.

Sex. Equal incidence in males and in females, but predominance of females with PF in Tunisia and Colombia.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

An autoimmune disorder. Loss of cell-to-cell adhesion in the epidermis (acantholysis). Occurs as a result of circulating antibodies of the IgG class, which bind to desmogleins, transmembrane glycoproteins in the desmosomes, members of the cadherin superfamily. In PV, desmoglein 3 (in some, also desmoglein 1). In PF, desmoglein 1. Autoantibodies interfere with calcium-sensitive adhesion function and thus induce acantholysis.

Clinical Manifestation

Pemphigus Vulgaris usually starts in the oral mucosa, and months may elapse before skin lesions occur. Less frequently, there may be a generalized, acute eruption of bullae from the beginning. No pruritus but burning and pain in erosions. Painful and tender mouth lesions may prevent adequate food intake. Epistaxis, hoarseness, dysphagia. Weakness, malaise, weight loss.

Skin Lesions. Vesicles and bullae with serous content, flaccid (flabby) (Fig. 6-9), easily ruptured, and weeping (Fig. 6-10), arising on normal skin, randomly scattered, discrete. Localized (e.g., to mouth or circumscribed skin area), or generalized with a random pattern. Extensive erosions bleed easily (Fig. 6-11), crusts particularly on scalp. Since blisters rupture so easily, only painful erosions in many patients (Fig. 6-11).

Figure 6-9. Pemphigus vulgaris This is the classic initial lesion: flaccid, easily ruptured bulla on normal-appearing skin. Ruptured vesicles lead to erosions that subsequently crust as seen in the two smaller lesions.

Figure 6-10. Pemphigus vulgaris Widespread confluent flaccid blisters on the lower back of a 40-year-old male who had a generalized eruption including scalp and mucous membranes. The eroded lesions are extremely painful.

Figure 6-11. Pemphigus vulgaris Widespread confluent erosions that are very painful and bleed easily in a 53-year-old male. There are hardly any intact blisters because they are so fragile and break easily. The blood tracts go sideways because the patient had been lying on his right side before the photograph was taken.

Nikolsky Sign. Dislodging of normal-appearing epidermis by lateral finger pressure in the vicinity of lesions, which leads to an erosion. Pressure on bulla leads to lateral extension of blister.

Sites of Predilection. Scalp, face, chest, axillae, groin, umbilicus. In bedridden patients, there is extensive involvement of back (Fig. 6-11).

Mucous Membranes. Bullae rarely seen, erosions of mouth (see Section 35) and nose, pharynx and larynx, vagina.

Pemphigus Foliaceus has no mucosal lesions and starts with scaly, crusted lesions on an erythematous base, initially in seborrheic areas.

Skin Lesions. Most commonly on face, scalp, upper chest, and abdomen. Scaly, crusted erosions on an erythematous base (Fig. 6-12). In early or localized disease, sharply demarcated in seborrheic areas; may stay localized or progress to generalized disease and exfoliative erythroderma. Initial lesion also a flaccid bulla, but this is rarely seen because of superficial location (see dermatopathology below).

Figure 6-12. Pemphigus foliaceus The back of this patient is covered by scaly crusts and superficial erosions.

Other Types (See Table 6-2)

Pemphigus Vegetans (PVeg). A PV variant. Usually confined to intertriginous regions, perioral area, neck, and scalp. Granulomatous vegetating purulent plaques that extend centrifugally. In these patients, there is a granulomatous response to the autoimmune damage of PV (Fig. 6-13).

Figure 6-13. Pemphigus vegetans Papillomatous, cauliflower-like, oozing growths in the groin and pubis of a 50-year-old man.

Drug-Induced PV. Clinically identical to sporadic PV. Several different drugs implicated, most significantly, captopril and D-penicillamine.

Brazilian Pemphigus (Fogo Selvagem). A distinctive form of PF endemic to south central Brazil. Clinically, histologically, and immunopathologically identical to PF. Patients improve when moved to urban areas but relapse after returning to endemic regions. Probably related to an arthropod-borne infectious agent, with clustering similar to that of the black fly—simulium nigrimanum. More than 1000 new cases per year are estimated to occur in the endemic regions.

Pemphigus Erythematosus (PE). Synonym: Senear-Usher syndrome. A localized variant of PF largely confined to seborrheic sites. Erythematous, crusted, and erosive lesions in the “butterfly” area of the face, forehead, and presternal and interscapular regions. May have antinuclear antibodies.

Drug-Induced Pemphigus PF. As in PV, associated with D-penicillamine and less frequently by captopril and other drugs. In most, but not all, instances, the eruption resolves after termination of therapy with the offending drug.

Neonatal Pemphigus. Very rare, transplacental transmission from diseased mother; spontaneous resolution.

Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

This is a disease sui generis and is discussed in Section 19.

Laboratory Examinations

Dermatopathology. PV: Light microscopy (select early small bulla or, if not present, margin of larger bulla or erosion): Separation of keratinocytes, suprabasally, leading to split just above the basal cell layer and vesicles containing separated, rounded-up (acantholytic) keratinocytes. PF: Superficial form with acantholysis in the granular layer of the epidermis.

Immunopathology. Direct immunofluorescence (IF) staining reveals IgG and often C3 deposited in lesional and paralesional skin in the intercellular substance of the epidermis. In PE Ig and complement deposits also found at the dermal epidermal junction.

Serum. Autoantibodies (IgG) detected by indirect IF or ELISA. Titer usually correlates with activity of disease. In PV, autoantibodies against a 130-kDa glycoprotein, desmoglein 3, located in desmosomes of keratinocytes. In PF, autoantibodies to a 160-kDa intercellular (cell surface) antigen, desmoglein 1, in desmosomes of keratinocytes.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

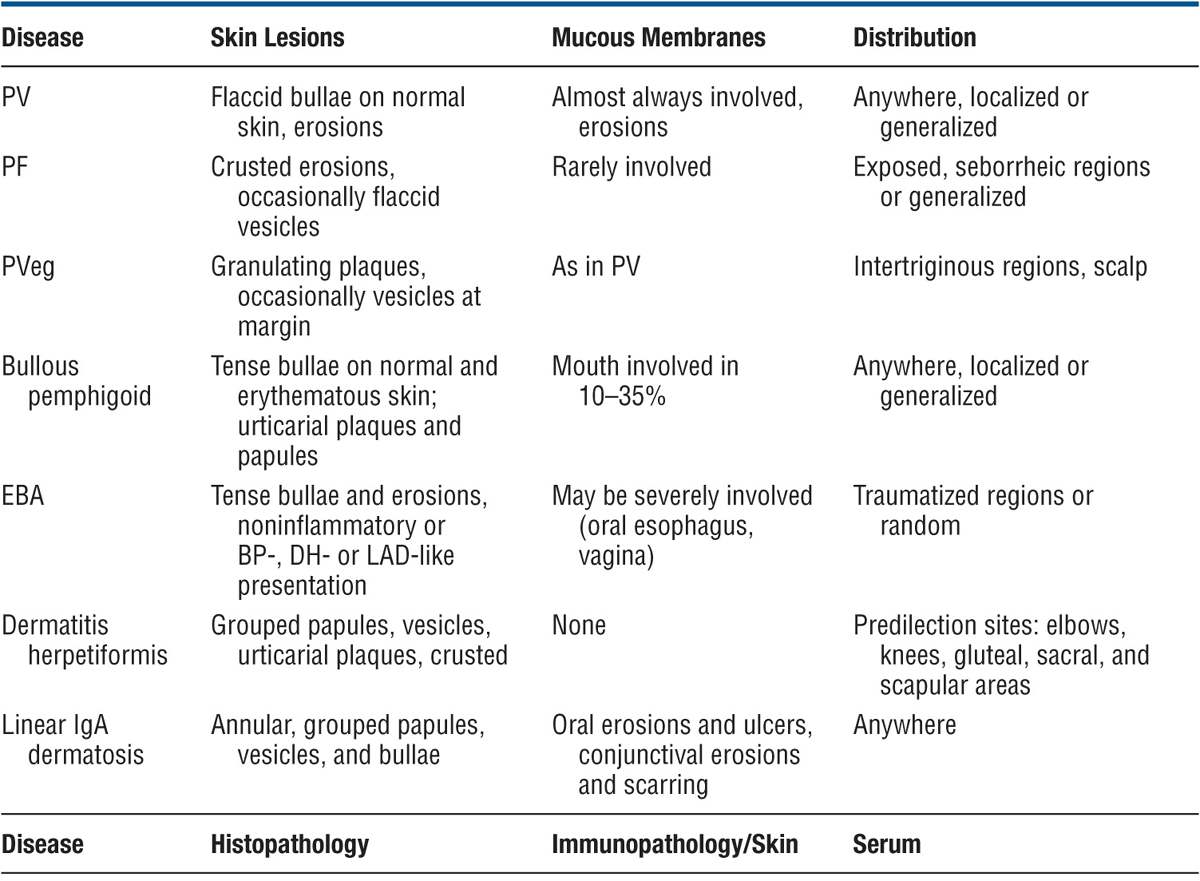

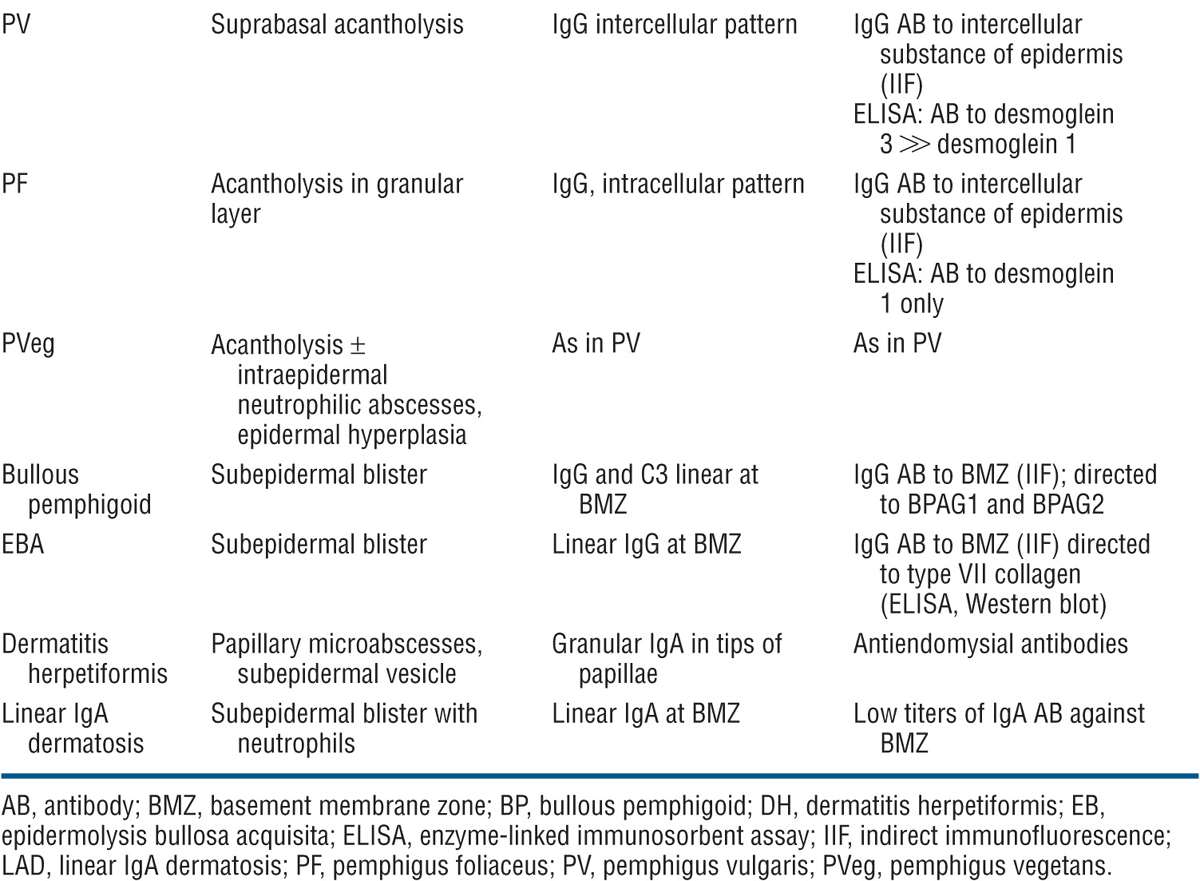

Difficult problem if only mouth lesions are present. Aphthae, mucosal lichen planus, erythema multiforme. Differential diagnosis includes all forms of acquired bullous diseases (see Table 6-3). Biopsy of the skin and mucous membrane, direct IF, and demonstration of circulating autoantibodies confirm a high index of suspicion.

TABLE 6-3 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF IMPORTANT BULLOUS DISEASES

Course

In most cases, the disease inexorably progresses to death unless treated aggressively with immunosuppressive agents. The mortality rate has been markedly reduced since treatment has become available. Currently, morbidity mainly related to glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapies.

Management

Requires expertise and experience. Treatment to be performed by dermatologist.

Glucocorticoids. 2-3 mg/kg body weight of prednisone until cessation of new blister formation and disappearance of Nikolsky sign. Then rapid reduction to about half the initial dose until patient is almost clear, followed by very slow tapering of dose to minimal effective maintenance dose.

Concomitant Immunosuppressive Therapy. Immunosuppressive agents are given concomitantly for their glucocorticoid-sparing effect:

Azathioprine, 2-3 mg/kg body weight until complete clearing; then tapered.

Methotrexate, either orally or IM at doses of 25-35 mg/wk. Dose adjustments are made as with azathioprine.

Cyclophosphamide, 100-200 mg daily, with reduction to maintenance doses of 50-100 mg/d. Alternatively, cyclophosphamide “bolus” therapy with 1000 mg IV once a week or every 2 weeks in the initial phases, followed by 50-100 mg/d po as maintenance.

Mycophenolate mofetil (1 g twice daily).

Plasmapheresis, in conjunction with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents.

High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (2 g/kg body weight every 3-4 weeks) has glucocorticoid-sparing effects.

Rituximab (monoclonal antibody to CD20) targets B cells, the precursors of (auto) antibody-producing plasma cells. Given as intravenous therapy once a week for 4 weeks shows dramatic effects in some and at least partial remission in other patients. Serious infections may be seen.

Other Measures. Cleansing baths, wet dressings, topical and intralesional glucocorticoids, antimicrobial therapy in documented bacterial infections. Correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance.

Monitoring. Clinical, for improvement of skin lesions and development of drug-related side effects. Laboratory monitoring of pemphigus antibody titers and for hematologic and metabolic indicators of glucocorticoid- and/or immunosuppressive-induced adverse effects.

ICD-10:Q 81

ICD-10:Q 81

A spectrum of rare genodermatoses in which a disturbed coherence of the epidermis and/or dermis leads to blister formation following trauma. Hence, the designation mechanobullous dermatoses.

A spectrum of rare genodermatoses in which a disturbed coherence of the epidermis and/or dermis leads to blister formation following trauma. Hence, the designation mechanobullous dermatoses. Disease manifestations range from very mild to severely mutilating and even lethal forms that differ in mode of inheritance, clinical manifestations, and associated findings.

Disease manifestations range from very mild to severely mutilating and even lethal forms that differ in mode of inheritance, clinical manifestations, and associated findings. Classification based on the site of blister formation distinguishes three main groups: epidermolytic or EB simplex, junctional EB (JEB), and dermolytic or dystrophic EB (DEB).

Classification based on the site of blister formation distinguishes three main groups: epidermolytic or EB simplex, junctional EB (JEB), and dermolytic or dystrophic EB (DEB). In each of these groups, there are several distinct types of EB based on clinical, genetic, histologic, and biochemical evaluation.

In each of these groups, there are several distinct types of EB based on clinical, genetic, histologic, and biochemical evaluation. ICD-10: L10

ICD-10: L10

A serious, acute or chronic, bullous autoimmune disease of skin and mucous membranes based on acantholysis.

A serious, acute or chronic, bullous autoimmune disease of skin and mucous membranes based on acantholysis. Two major types: pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF).

Two major types: pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF). PV: flaccid blisters on skin and erosions on mucous membranes. PF: scaly and crusted skin lesions.

PV: flaccid blisters on skin and erosions on mucous membranes. PF: scaly and crusted skin lesions. PV: suprabasal acantholysis. PF: subcorneal acantholysis.

PV: suprabasal acantholysis. PF: subcorneal acantholysis. IgG autoantibodies to desmogleins, transmembrane desmosomal adhesion molecules.

IgG autoantibodies to desmogleins, transmembrane desmosomal adhesion molecules. Serious and often fatal unless treated with immunosuppressive agents.

Serious and often fatal unless treated with immunosuppressive agents.