36 Outcomes and Reducing Complications in Breast Reduction

Summary

Breast reduction is a highly successful procedure but carries the potential for significant complications. This chapter outlines the main areas of concern, causes of complications, how to prevent them, and then how to deal with them once they have occurred.

Key Teaching Points

Understanding patients’ motivations and expectations is crucial in deciding which patients are good candidates for a reduction operation.

Periareolar and vertical scars generally heal with less hypertrophy and widening than inframammary fold scars.

The potential for lactation function is maximized when a major portion of the parenchyma and breast ductal system is preserved beneath the nipple.

Removal and tightening of breast skin should not be relied on to control and shape the breast—breast shape is influenced by resection of breast parenchyma.

It is not what is removed, but rather what is left behind that really matters in reduction surgery.

Patients should be warned that sensory return after a free nipple graft is unpredictable.

The distance from the nipple to the inframammary crease must be progressively longer as breast volume increases.

The nipple’s relationship to the inframammary crease is more important than measurements taken from the clavicle.

The larger the breast preoperatively, the greater the likelihood the postoperative breast will spring upward after the resection, leaving the nipple–areola too high.

Bottoming out occurs in all forms of reduction mammaplasty.

Breast reduction should be planned to reduce the potential for fat necrosis and folded pedicles that can complicate mammographic interpretation.

Fat necrosis presents as areas of whorled calcification rather than the fine stippling seen with cancer.

Regardless of the technique used, the greater the reduction resection, the greater the likelihood of impaired nipple sensation.

A patient may elect to undergo breast conservation therapy with postoperative radiation if tumor margins are clear after reduction surgery; if the margins are not clear, mastectomy should be performed.

36.1 Reducing Complications

Breast reduction is a commonly performed plastic surgical procedure and confers considerable health benefits on our patient population. Given the degree of skin undermining, lengthy scars and somewhat random nature of the pedicles used, complications can become significant. It is also one of the more litigated aspects of plastic and reconstructive surgery. An intimate understanding is required of the anatomy, risk factors, and the procedures available to correct the variations in breast morphology with which we are faced.

Problem Areas

Hollow upper poles in patients with involutional atrophy and severe ptosis.

Lateral fullness with poor lateral crease definition.

Adjacent upper abdominal fullness.

Dealing with elderly patients greater than 70 years of age.

Dealing with patients with high-risk breast disease.

Cancer found at the time of breast reduction.

Complications in Breast Reduction

Hematoma.

Infection.

Skin necrosis and delayed healing.

Inadequate reduction.

Dog-ears.

Asymmetry.

Nipple–areola problems.

Sensory loss.

Hypertrophic scarring.

Fat necrosis.

Over-reduction with upper pole deficiency.

36.2 Problem Areas

36.2.1 Reduced Augmentation for Upper Breast Fullness

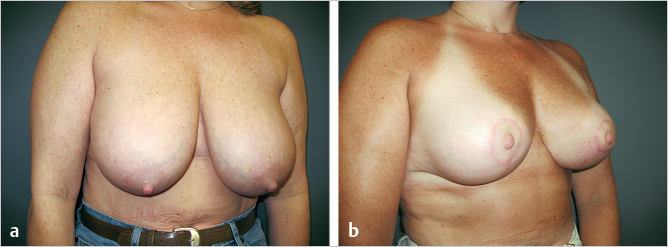

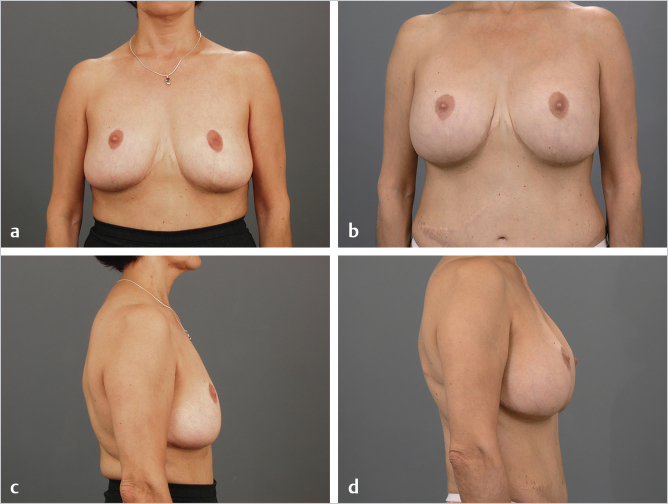

Patients with involutional atrophy of the upper poles and significant ptosis want smaller breasts but often desire a youthful fullness in the upper aspect. If significant ptosis accompanies the hypertrophy and practically all of the breast tissue is below the nipple–areolar complex (NAC), reduction mammaplasty with any of the techniques described previously will not permanently restore upper breast fullness. Bottoming out occurs in all forms of reduction mammaplasty, albeit somewhat less in the superior and superomedial approaches.

Good, long-lasting correction can be achieved by placing an implant in the dual-plane position with overlying reduction to achieve upper pole fullness. This strategy is particularly helpful in providing more permanent corrections for women with stretched, inelastic breast skin. Before this approach is chosen, it must be discussed in detail with the patient as it will commit her to implant maintenance and surveillance. Third-party providers and managed care companies may not reimburse for this procedure, given the fact that an implant is being added to a breast reduction. The approach merits consideration in this patient group to ensure satisfaction.

Technical Pearl

When combining breast reduction with an implant insertion, I prefer to move the nipple–areola up on a superior or superomedial pedicle, rather than using an inferior pedicle. This maximizes the nipple–areolar blood supply.

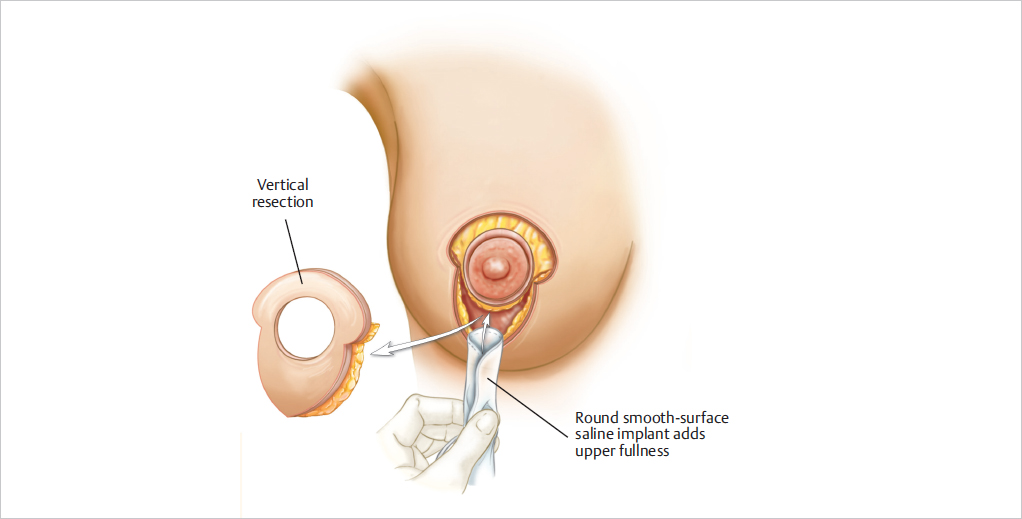

Dissection of the pocket for the breast implant may detach perforators when the area to be augmented is elevated beneath the inferior pedicle. If a Wise pattern skin resection is used, there should be no tension on the closure of the T juncture. The final breast form depends on the implant placement and preserved parenchyma, not on a tight skin closure (▶Fig. 36.1).

This technique can be used to obtain symmetry with an opposite breast reconstruction in which an implant or a postoperatively adjustable implant has been placed. Bilateral implants usually provide better long-term symmetry. When the final size is not fully defined, an adjustable implant can be used beneath both breasts to permit the patient to more accurately determine the desired final size and the surgeon to have more versatility in creating a symmetrical result (▶Fig. 36.2).

36.2.2 Liposuction and Surgical Excision to Treat Lateral, Axillary, and Presternal Fullness

Patients with mammary hypertrophy frequently complain of lateral chest wall fullness where the axillary tail of the breast blends into the roll of fat extending around the posterior axillary fold. This condition should be pointed out to the patient before the initial procedure and addressed at the time of the reduction mammaplasty. If extra lateral tissue is not removed, considerable fullness will persist in this region, and the lateral breast crease will be poorly defined.

Technical Pearl

The lateral tissue should be removed low and at the level of the inframammary fold with liposuction (my preference) or by excision.

Liposuction has the advantage of being able to feather the contour into the surrounding tissue and reduces the likelihood of seroma formation compared with a pyramidal wedge resection toward the axilla. Average liposuction volumes in this area are between 200 and 300 g but can be significantly higher in very large patients. Patients should be warned that the suctioned area may be more painful than the breasts postoperatively.

Anterior axillary fold and presternal fullness are also successfully managed with standard liposuction. This is particularly true in patients with gynecomastia. Ultrasound-assisted liposuction is more effective for cavitating and liquefying the fibrous parenchyma associated with gynecomastia; however, until further data on its safety for this application are evaluated, it is not recommended for reducing the female breast. Smaller degrees of deformity are reduced by standard liposuction through the reduction incision. Any thickening or mass remaining postoperatively is easily approached and excised (▶Fig. 36.3).

36.2.3 Liposuction for Abdominal Contouring

A distinct fatty roll in the upper abdomen is often accentuated and may appear larger than it really is if reduction mammaplasty is performed on a pendulous breast. Patients with this problem are often pleased with the results of upper abdominal and low chest wall liposuction.

36.3 Postoperative Considerations

After breast reduction, the incisions are covered with Steri-Strips, gauze, and a soft brassiere. The following day the patient can remove the dressing down to the Steri-Strips and shower without massaging or disturbing the breast area. If a drain has been placed, I remove it between 1 and 5 days after surgery when output is consistently less than 30 cc/d. Activities requiring raising the arms overhead are avoided for 4 to 6 weeks to prevent strain and pull on the incisions, which could result in widened scars.

Exposure to cigarette smoke should be avoided completely as it may compromise nipple–areolar vascularity and contribute to fat necrosis within the breast.

Breast sensation is predictably diminished for the first weeks to months after breast reduction. Patients are alerted to this condition and cautioned not to be alarmed by it. Sensory return and reinnervation can be accompanied by dysesthesias and paresthesias. To minimize these sensations, I ask patients to desensitize the breasts with massage. Data suggest that superior pedicle techniques are associated with a greater incidence of initial nipple numbness than inferior pedicle techniques, although sensation seems to be similar between the two groups by 12 months postoperatively.

36.4 Special Problems

36.4.1 Elderly Patients

I do not recommend breast reduction in women of 70 years or older, unless, after taking the history, performing a physical examination, and consulting with their personal physician, I am assured of their good health, appropriate motivation, and compelling physical findings and symptoms. If the nipple–areola needs to be moved to a considerable distance, I consider a free nipple graft. This technique increases the likelihood of nipple–areolar survival and avoids the very real risk of nipple–areolar loss from transposition and fat necrosis (▶Fig. 36.4).

Because women in this age group are prone to fat necrosis (it can sometimes even occur spontaneously), I try to reduce their breasts with a simple transverse excision and avoid complex techniques associated with an inferior or superomedial pedicle.

36.4.2 Women at Risk for Breast Cancer

When a woman is at high risk for breast cancer or has had breast cancer in one breast, breast reduction poses special concerns in that residual parenchymal scarring can make it difficult to differentiate breast cancer from normal tissue. I recommend preoperative mammograms for all of my patients at high risk for breast cancer. Questionable areas should be evaluated, consultation with a surgical oncologist considered, and biopsies performed.

Breast reduction operations, particularly in women at risk, should be planned to reduce the potential for fat necrosis and folded pedicles that can complicate mammographic interpretation. When fat undergoes necrosis, it becomes firm and can mimic a malignancy or develop later calcifications visible on a mammogram, presenting problems in monitoring for the woman and her physicians.

Technical Pearl

Fortunately, fat necrosis presents as areas of whorled calcification rather than the fine stippling or “stardust” seen with cancer.

Oncoplastic reduction has become a mainstream adjunctive technique in the treatment of breast cancer in patients with large breasts who will be facing radiation and wish to conserve their breasts rather than undergo mastectomy. Reducing the breast prior to radiation greatly reduces the risk of fat necrosis and severe shrinkage of the breast downstream. It is also indicated in smaller-breasted women wishing to preserve their breasts but requiring some degree of reshaping with local breast flaps in order to achieve a satisfactory aesthetic outcome following lumpectomy prior to radiation therapy. These techniques will be outlined in Chapter 61.

The woman and surgeon should become familiar with the feel of the patient’s breasts after reduction. Any change or new lump must be explained. Mammography is performed 9 months postoperatively for women over 30 years of age and then at yearly intervals, along with breast self-examination and yearly physician evaluation. The radiologist should be familiar and comfortable with interpreting mammograms for patients who have had aesthetic breast surgery.

Breast reconstruction in patients who have had a previous breast reduction is a difficult problem. Their breast skin is often thin. The lower flaps at the T are thin and subject to necrosis and delayed healing, although the argument can be made that these flaps have undergone a form of vascular delay procedure in the past.

36.4.3 Cancer Found at the Time of Breast Reduction

Cancer found at the time of breast reduction has potentially serious medicolegal implications. Breast reduction does not cause cancer; in fact, the risk of breast cancer has been shown to be slightly reduced after the resection of a significant amount of breast tissue. It is still imperative, however, that patients continue to perform breast self-examination and have regular mammograms at the appropriate age. In a recent study by Tang and colleagues, patients diagnosed with breast cancer at the time of breast reduction were shown to have earlier-stage lesions with a higher incidence of node-negative lesions. Their survival was also higher at 88% as opposed to a 77% survival for matched control subjects in the general population. Similarly, Brinton and colleagues found that patients who underwent previous breast reductions and then developed breast carcinoma had a lower risk than unreduced patients.

Technical Pearl

A patient may elect to undergo breast conservation therapy with postoperative radiation if the tumor margins are clear after reduction surgery. If the margins are not clear, mastectomy should be performed, because it will be nearly impossible to accurately identify the original tumor bed for safe re-excision.

36.5 Complications

The complications of breast reduction fall into two broad categories: aesthetic and operative. Most complications can be avoided by careful patient selection and preoperative planning. The most common aesthetic shortcomings of reduction mammaplasty are failure to sufficiently reduce the breast, asymmetries, dog-ears, unattractive scars, nipple–areolar problems relating to malposition and diminished vascularity, and over-reduction. Frequently, secondary procedures are required for correction of these conditions. These are usually delayed for 1 year after the initial operation to allow sufficient time for the breasts to heal and settle and a plan to be formulated.

36.5.1 Hematoma

Incidence: Less than 1%.

Occurrence: Typically, within the first 12 hours after surgery and are usually unilateral.

Signs and symptoms: Increasing pain, swelling, and bruising of the affected side and may be associated with evidence of vascular impairment to a previously viable nipple or skin envelope resulting from tension-induced ischemia. Bleeding intercostal perforators are the most common source.

Treatment: Surgical evacuation and sealing of the bleeding point. Late postoperative hematomas may occur 10 to 14 days after surgery when clot dissolution coupled with straining or sudden movements may trigger a bleed. Patients should not exercise or perform vigorous activities for 6 weeks after reduction surgery.

36.5.2 Seromas

Incidence: 1 to 5%.

Signs and symptoms: Swelling of the breast, usually without skin discoloration; fluid thrill may be palpable.

Treatment: Aspiration is usually adequate to deal with the problem, but ultrasound-guided aspiration with insertion of a seroma drain may be required in difficult cases. Instillation of 100 mg of doxycycline through a drain tube for 30 minutes, followed by evacuation, can help in reducing recurrence.

36.5.3 Infection

Incidence: Infection in the form of cellulitis requiring antibiotic agents, or abscess formation, is fortunately rare in the author’s experience, with an incidence of 1%.

Signs and symptoms: Erythema of the breast, swelling, and induration. If abscess formation is present, fluctuation is often palpable.

Diagnosis: Primarily made on clinical grounds. White blood count is usually elevated. Ultrasound of the breast may demonstrate a complex loculated fluid collection at the site of abscess formation.

Treatment: Cellulitis is treated effectively with antibiotic agents. Abscesses require open drainage and are usually a consequence of infection within an undiagnosed hematoma when accompanying breast reduction. Davis and colleagues reported a 12% incidence of cellulitis requiring antibiotic therapy, a figure that seems high. Dabbah and colleagues reported a 22% incidence of infection and fat necrosis using inferior pedicle techniques, which also seems unduly high. In my personal series of over 1,200 breast reductions, I have seen only one abscess and cellulitis occurring in less than 1%. Careful attention to detail, the use of alcohol–chlorhexidine–based skin preps (Chlora-Prep), appropriate use of perioperative antibiotic agents, and saline solution lavage of the reduction site before closure all help to minimize infection rates.

36.5.4 Skin Necrosis and Wound Healing Problems

Causes of skin necrosis:

Tension at T closure.

Wide undermining of thin skin flaps.

Operating on high-risk patients, for example, smokers.

Incidence: Unclear and obviously related to clinical judgment, surgical expertise, technique, and procedure selected.

Skin necrosis is often tension-related in the Wise pattern reductions and is virtually absent in vertical techniques. In the Wise pattern closures, tension at the inverted-T closure compromises blood flow to the tips of the skin flaps and necrosis occurs.

Technical Pearl

It is crucial to steal tension in from lateral to medial when closing, thereby ensuring that the flap tips are under no tension whatsoever. It is also important to avoid undermining the tips of these flaps to help maintain good vascularity to the tissues.

Skin necrosis and wound healing complications occur more frequently than invasive infection; Davis and colleagues reported a 19% incidence of wound healing problems related to skin viability underneath the breast (▶Fig. 36.5). Lejour and colleagues noted a 5.4% incidence of delayed healing at the inframammary crease associated with vertical reductions and wound healing problems that were directly proportional to the preoperative breast size and quantity of fat within the breast. Much of the delayed healing at the base of the vertical closure is related to purse-string type closures to minimize dog-ear formation rather than true skin necrosis. In my experience, minimizing the size of the inferior dog-ear deformity and paying careful attention to meticulous closure of the vertical incision are crucial to improving wound healing at this site. I no longer use purse-string closure at the base of the vertical incision in vertical reductions and delayed healing is now almost nonexistent.

Reductions attempted in high-risk patients, or extensive undermining beneath breast flaps, cause ischemia often accompanied by skin necrosis. This is graphically demonstrated in ▶Fig. 36.6. The patient was a heavy smoker referred for a second opinion having undergone an inferior pedicle reduction. She developed extensive tissue necrosis in the left breast resulting in delayed healing for almost 6 months, leaving her with severe deformity and asymmetry (▶Fig. 36.6).

36.5.5 Inadequate Reduction

Cause: Inadequate reduction tends to be more of a problem for the neophyte than for experienced surgeons. It can be a problem with vertical techniques due to an unwillingness to thin the pedicle adequately when first learning this approach. In inferior pedicle reductions, failure to debulk the inferolateral and inferomedial corners of the breast flaps cause “boxy breast” deformity, while an excessively large pedicle contributes to excess bulk in the lower pole of the reduced breast. The guide for estimating resection volumes should provide a rough estimate of how much tissue to resect for any given breast size. If a patient is planning significant weight loss after surgery, she should either defer her reduction until after weight loss has been achieved or reduction should be deliberately more conservative in an effort to prevent the excess volume loss later.

Inadequate reduction during the primary procedure, breast regrowth, or weight gain and consequent breast enlargement are the most frequent reasons for patients to request reoperation. Other patients, although initially satisfied, find that after weight gain, pregnancy, or lactation, their breasts enlarge and do not involute to their smaller, reduced size. Young patients who have a reduction mammaplasty before the completion of breast growth may also need a secondary reduction mammaplasty.

Treatment: Correction of inadequate production requires either of the following:

Redo reduction.

Localized excision of areas of fullness.

Localized liposuction.

This 32-year-old patient had reduction mammaplasty 5 years before her consultation for a second reduction procedure. Immediately postoperatively, she believed that her breasts had not been reduced enough. The original operative note showed that an inferior pedicle reduction technique was used. A transverse wedge resection was used to debulk the lower pole across the entire breast base without disturbing the NAC which was already in the correct position. She declined suction revision of the medial dog-ears as she was happy with the outcome. The patient is shown 1 year after her second reduction mammoplasty (▶Fig. 36.7).

Boxy breast deformity is another problem caused by inadequate inferolateral/inferomedial resections, particularly prevalent when using a Wise pattern–based technique. Failure to empty the medial and lateral inframammary quadrants causes fullness in these areas, contributing to the appearance of lower pole squareness, as seen in this patient who had been reduced 10 years prior and who complained of boxy shape and high-riding nipples (▶Fig. 36.8). Redo reduction through a traditional inferior pedicle technique was performed with some improvement, but the nipples were not lowered as the patient did not want scars above the areolar borders. Overall breast shape continues to give a pseudoptotic appearance, as the nipples could not be lowered to restore balance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree