36 Facial Rejuvenation: Open Technique

Abstract

In the last few decades, facial aesthetic surgery has made enormous progress. A deeper understanding of the anatomy of facial aging and the development of new technologies and cosmetic procedures not only helped to improve the treatment of facial flaccidity, but also represented important tools in perioperative care. The redundant facial skin that usually is observed in elderly patients due to the aging process occurs at a much earlier age in massive weight loss patients and can lead to social embarrassment and psychological distress. This chapter presents the surgical treatment of the face in the patient after massive weight loss, emphasizing the correct repositioning techniques applied to the facial flaps, namely, the Pitanguy “round-lifting” technique and the forehead coronal “block” lifting and subperiosteal approach. These principles, which have evolved over 40 years of experience, have offered consistent and satisfactory results.

Introduction

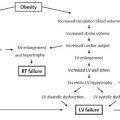

Facial aesthetic surgery has demonstrated enormous progress in the past few decades, due to a greater understanding of anatomy and the development of newer technologies and cosmetic procedures that complement the basic operation. In our beauty-centered global society, where life is fast-paced, people are rapidly judged by their appearance. Thus, the face is frequently the focus of a person’s anxiety, especially in individuals who are experiencing job competition and tense interpersonal relationships, motivating these patients to seek plastic surgery for a more youthful look. Bariatric surgery has permitted significant loss of weight in the morbidly obese. It has therefore become more common for the patient who has undergone a great amount of weight reduction to present to the plastic surgeon and request the removal of excess skin, from one region, or more typically, many regions of the body. Specifically, the redundant facial skin can cause social embarrassment and needs to be addressed by a surgical procedure, as the face is not as easily concealed as other parts of the body.

Indications

The surgeon must be knowledgeable in the details of different surgical approaches and variations to attain the best result for each patient. The Pitanguy “round-lifting” technique, as described by the senior author, is indicated for the treatment of excess facial skin in the massive weight loss patient, as the vectors reposition tissues without causing anatomic distortion, such as dislocation of the hairline and visible signs of skin traction.

The surgical treatment of the aging face in the patient with massive weight loss is presented here, emphasizing the correct repositioning applied to the facial flaps and the forehead, thus ensuring that all anatomic landmarks are precisely preserved. Patient assessment is discussed, and technical aspects are detailed and illustrated. Finally, complementary surgical procedures that may be useful are presented, with a brief discussion of indications.

Technique

A satisfactory outcome of an aesthetic facial procedure is attained when signs of an operation are undetectable and anatomic landmarks have been preserved. Visible scars and dislocation of the hairline are among the most common complaints, and great care must be exercised to avoid these stigmata. The Pitanguy round-lifting technique has evolved from these concerns.

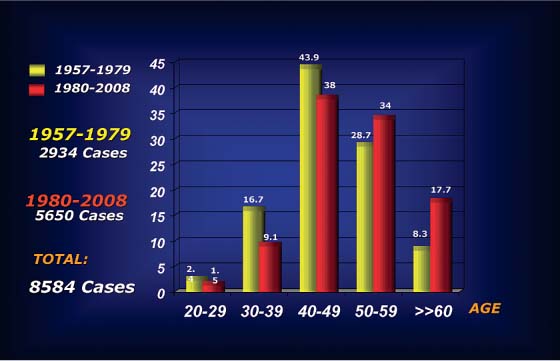

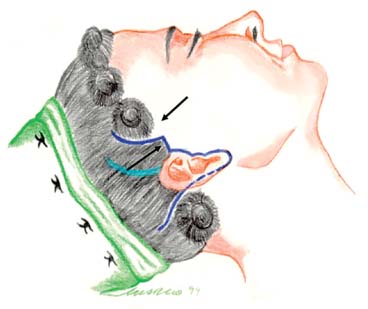

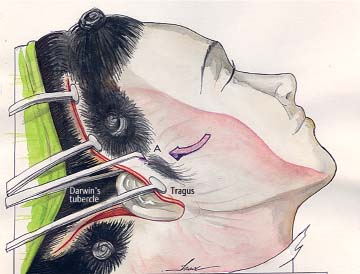

Photographic studies with computerized analysis were done in the same patient at different ages, determining the parameters of change that occurred during the aging process. The sample for this research was restricted to a group of 40 white female patients with a history of limited exposure to the sun and who first presented to our service in their childhood, usually for the correction of prominent ears, and returned later for additional surgery, such as rhinoplasty, and finally, at a more advanced age, returned for facelifting. All photographs were taken under the same conditions for preoperative documentation. The choice of aging parameters was based on facial changes that occurred over a period of time, so that the first photograph of each patient was used as a pattern for the subsequent study. The computer model suggests that the most adequate direction of repositioning of the facial flaps is the one described in the Pitanguy round-lifting technique. A line connecting the tragus to Darwin’s tubercle represents the best direction for repositioning of the aging face, with less tension exerted.1,2 Clinically, this has proven to be the most appropriate method for repositioning the facial tissues. Rhytidoplasty is one of the most frequently performed surgeries in the practice of plastic surgeons.3–9 In the senior author’s private clinic, a total of 8584 personal consecutive cases have been analyzed to date ( Fig. 36.1 ).

Combined procedures, when properly indicated, are helpful in selected cases. They are performed only by a well-trained and highly qualified team. The advantage of this approach is that different operations can be performed at the same time, the surgeon still being the one to perform all the essential steps of the surgery, while the assistant surgeons attend to the final aspects of the procedures.10–13 Our experience with combined procedures in patients with weight loss is shown in Table 36.1 . Weight loss was determined by a specialized medical team; this ranged from 10% (9 kg) to 43% (135 kg) of patient weight, with an average of 12 months required to achieve this plateau. The majority of the patients were female (75%), but more recently a noticeable increase in male patients has been noted. In the 1970s, men represented 6% of the patients seeking aesthetic procedures, and in the 1980s, about 15%; currently, 25% of patients who seek aesthetic surgery are men.

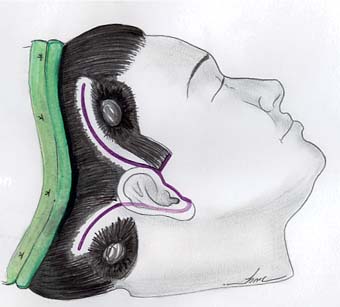

After appropriate intravenous sedation and preparation, local anesthesia infiltration is performed. The standard incision is outlined, beginning in the temporal scalp, proceeding into the preauricular area in such a way as to respect the anatomic curvature of this region. The incision then follows around the earlobe and, in a curving fashion, finishes in the cervical scalp ( Fig. 36.2 ). This S-shaped incision creates an advancement flap that prevents a step-off in the hairline, allowing the patient to wear her hair up without revealing the scar.

Variations of this incision are chosen depending on each case, such as a combined incision in the anterior hairline or with a prolongation inside the hair in cases of great excess of skin ( Figs. 36.3 and 36.4 ).14

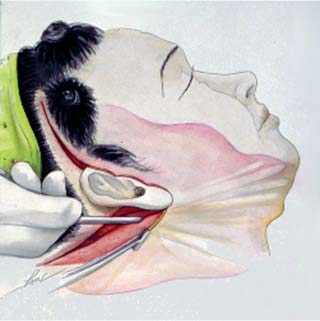

Undermining of the facial and cervical flaps is performed in a subcutaneous plane, the extension of which is variable and individualized for each case. A danger area lies beneath the non-hair-bearing skin over the temples, which we have called “no-man’s-land,” where most of the temporofrontal branches of the facial nerve and temporal artery are frequently found. The no-man’s-land is an area along a line connecting the tragus to the supraorbital rim.15,16 Dissection over this area should be superficial and hemostasis carefully performed.

Patients who have undergone a significant loss of weight usually complain of a very heavy, fatty neck. Treatment of this area requires that the dissection proceed all the way to the other side under the mandible. With the advent of suction-assisted lipectomy, submental lipodystrophy is primarily addressed by liposuction, in a criss-cross fashion ( Fig. 36.5 ). On the other hand, careful direct lipectomy using specially designed scissors may still be useful to defat the submental region, as has been described historically.17 Following this, treatment of medial platysmal bands is performed under direct vision. Approximation of diastasis is done with interrupted sutures, plicating down to the level of the hyoid bone. After this suture, the mandibular retaining ligaments are freed on each side of the submental incision, performing a superficial subcutaneous undermining from the medial to lateral area of the chin. This maneuver facilitates the correct replacement of the cervical flaps.

Undermining of the facial flaps is extended over the zygomatic prominence to free the retaining ligaments of the cheek and, in some cases, can reach the nasolabial fold. Dissection of the deeper elements of the face has evolved over the past 30 years. Almost no treatment was advocated before the publications that first described the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). The approach to this structure has been a topic of much discussion. Currently, we determine whether to dissect or simply plicate the SMAS only after subcutaneous dissection has been completed. Repositioning of the SMAS is done, noting the effects on the skin.

Although extensive undermining of the SMAS was performed in an earlier period, it has been noted that plication of this structure, with repositioning of the malar fat pad in a vertical direction, correcting what gravity has pulled down, has given satisfactory and natural results.18 The durability of this maneuver is relative to the individual aging process. Repositioning of the musculoaponeurotic system allows support of the subcutaneous layers, corrects the sagging cheek, and reduces tension on the skin flap.

Techniques that treat pronounced nasolabial folds include repositioning of the skin flaps and repositioning of the SMAS and the fascial fatty layer (malar fat pad), with variable results.18,19 Filling with different substances may also be done at the end of surgery, with either fat grafting or other material. When there is a very pronounced nasolabial fold, mainly in male patients, the direct excision of this fold is a technique that provides a definitive solution, with a barely noticeable scar that mimics the nasolabial fold itself.18

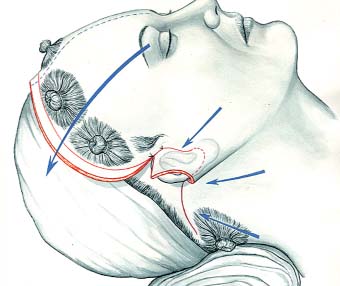

The direction of repositioning of the skin flaps is a fundamental feature of the Pitanguy round-lifting technique. In this manner, the undermined flaps are rotated rather than simply pulled, acting in a direction opposite to that of aging, and ensuring repositioning of tissues with preservation of anatomic landmarks. A second advantage in establishing a precise vector of rotation is that the opposite side is repositioned in the exact manner.6,9

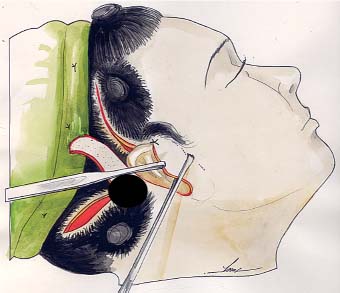

This vector of reposition connects the tragus to Darwin’s tubercle for the facial or anterior flap. A Pitanguy flap demarcator (Padgett Instruments, Kansas City, MO) is placed at the root of the helix to mark point A on the skin flap ( Fig. 36.6 ). The edge of the flap is then incised along a curved line crossing the supra-auricular hairline so that bald skin, not containing hair follicles, is resected. A key suture is located here.

Likewise, the cervical flap should be pulled in an equally precise manner, in a superior and slightly anterior vector of traction, to avoid a step-off of the hairline. Key stitches are placed to anchor the flap along the pilose scalp at point B so that there is no tension on the thin skin at the peak of the retroauricular incision. This incision creates an advancement flap that prevents a step-off in the hairline, allowing the patient to wear her hair up without revealing the scar.

Only when the temporary sutures have been placed will excess facial skin be resected. Skin is accommodated and demarcated along the natural curves of the ear, with no tension whatsoever ( Fig. 36.7 ). Final scars are thus not displaced or widened. The tragus is preserved in its anatomic position, and the skin of the flap is trimmed so as to perfectly match the fine skin of this region.

When performing a brow lift, placing these key sutures at points A and B is mandatory before any traction is applied to the forehead flap, essentially “blocking” the facial flaps7 from further movement.

Forehead Lifting

Weight-loss patients present significant excess skin in the face and neck, including the forehead. The upper face evidences a descent in the level of the eyebrow and the appearance of wrinkles and furrows, sometimes from an early age. These are a direct consequence of muscle dynamics and also due to loss of skin tone. The use of botulinum toxin has been a valuable adjunct to temporarily correct these lines of expression and has been widely indicated as a nonsurgical application, either by itself or as a complement to surgery.

Elements of the upper face that must be considered preoperatively for any procedure are the length of the forehead and the elasticity of the skin, muscle force and wrinkles, the position of the anterior hairline, and the quality and quantity of hair.7,20–22 An important decision to be made is the placement of the incisions. There are two classic approaches: the bicoronal incision and the limited pre-pilose or juxtapilose incision.23 The first allows for treatment of all elements that determine the aging forehead while hiding the final scar within the hairline. Certain situations, however, rule out this incision. Patients with a very long forehead or those who have already had surgery should not be considered for this incision, because they will have an excessively recessed hairline if the forehead is further pulled back.

Having “blocked” the facial flaps at points A and B, as described above, the forehead may be pulled in any direction, either straight backward or more laterally ( Fig. 36.8 ). The amount of scalp flap to be resected is determined by the length of the forehead and the effect that traction causes on the level of the eyebrows. The midline is positioned, demarcated, incised, and blocked with a temporary suture. Sometimes no traction is necessary, and no scalp is removed in the midline. Two symmetrical flaps are created, and lateral resection can now be performed, allowing the eyebrow to be raised as necessary ( Fig. 36.9 ).

The second approach is the juxtapilose incision,23 performed when the patient presents with ptosis of lateral eyebrow and scant lines of expression of the forehead. After the execution of a limited juxtapilose incision in the hairline, subperiosteal undermining is done in the whole forehead, reaching the superior orbital rim while preserving the supraorbital neurovascular bundle and frontal nerve. The orbital ligament near the zygomaticofrontal suture line and the periosteal attachments along the superior orbital rim and the temporal line are released by blunt dissection with a periosteal elevator. The elevation of the eyebrow and the frontal area as a whole is executed in a superolateral direction ( Fig. 36.10 ).

Endoscopic instrumentation has permitted treatment of the brow through minimal access and has proved useful in selected cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree