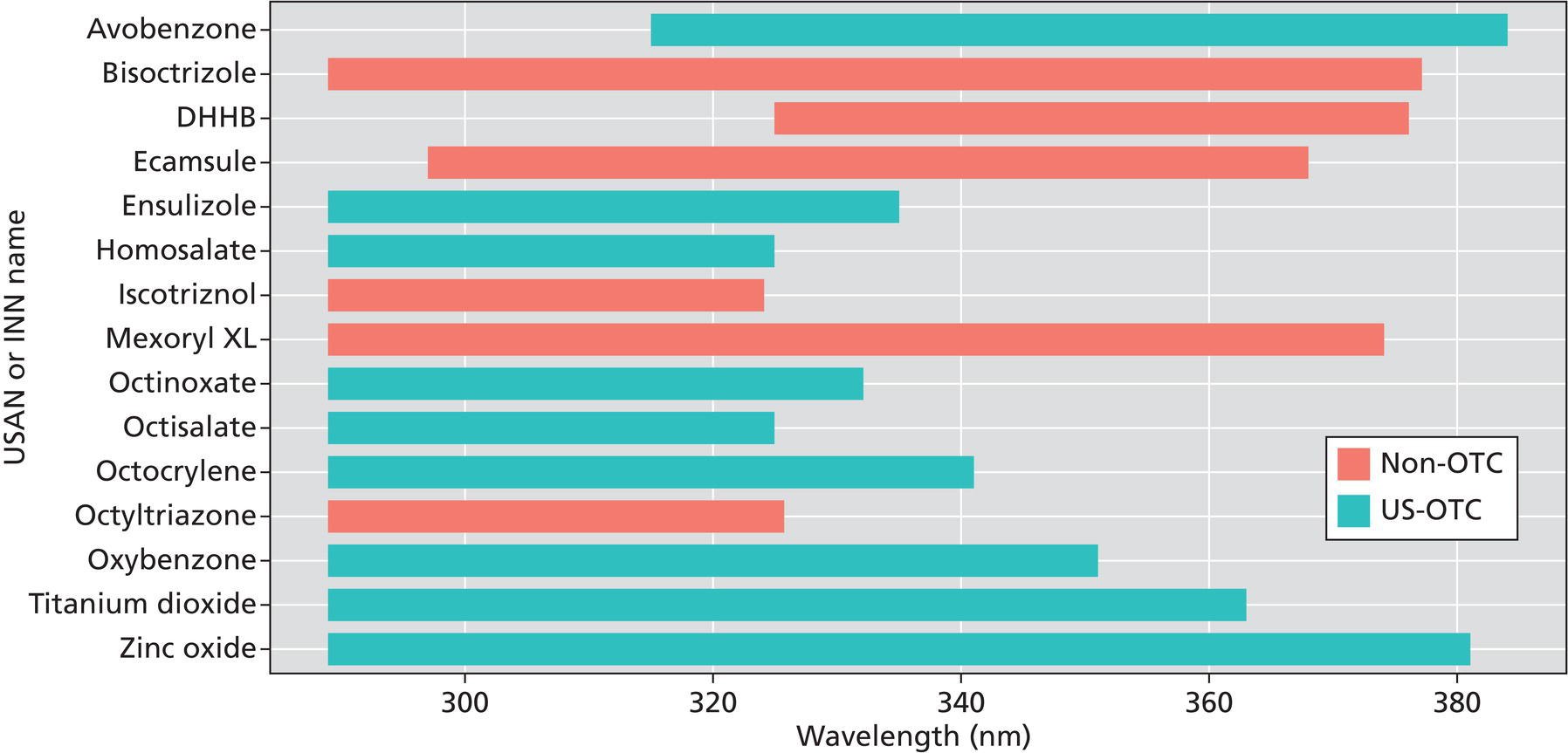

Angelike Galdi1, Peter Foltis1, Brian Bodnar1, Dominique Moyal2, and Christian Oresajo1 1 L’Oréal Research and Innovation, Clark, NJ, USA 2 La Roche‐Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique, Asnières sur Seine, France Human skin exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) from sunlight can cause many adverse effects. Therefore, it becomes necessary to protect the skin from damaging UVR through various means, one of which is through adequate application of sunscreen, especially when exposed to sunlight for prolonged periods of time. Ultraviolet (UV) light that reaches the surface of the Earth includes both UVB (290–320 nm) and UVA (320–400 nm). UVB rays are mainly responsible for the most severe damage being acute such as erythema (sunburn), and long‐term skin cancer included, and they can act by directly impacting deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and proteins [1]. In the case of sunscreens, the basis for measuring and reporting SPF uses erythema as an endpoint for subjects exposed to UVA and UVB radiation, yet erythema is mostly caused by UVB light (Figure 21.1). Although SPF can be understood only as a measure of protection from UVB light, it is important that while UVA rays are not directly absorbed by biological targets [3], they can still dramatically impair cell and tissue functions. In particular, UVA penetrates deeper into the skin than UVB. This particularly affects connective tissue, inducing the production of detrimental reactive oxygen species (ROS) which in turn damage DNA, cells, vessels, and tissues [4–9]. In addition, UVA light is a potent inducer of immunosuppression [10, 11] and contributes to the development of malignant melanomas and squamous cell carcinomas [12, 13]. Finally, photosensitivity and photodermatoses are primarily mediated by UVA radiation [14]. It is important to note that under all weather conditions, the UVA irradiance is at least 17 times higher than the UVB irradiance. For all these reasons, sunscreens must evidently contain both UVA and UVB filters to protect skin from these two associated harmful rays. In some zones, sunscreen products can be classified into two main categories according to their purpose: Sunscreen products can also be classified in terms of regulatory status. In the United States, all products with an SPF claim are regulated as over‐the‐counter drugs (OTC) by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [15]. Sunscreen products are classified as cosmetics in the European Union (EU), non‐EU European countries (e.g. Russia), most African and Middle‐Eastern countries, India, Latin America, and Japan. They are classified as “special” cosmetic products in China (special cosmetics), Korea and Ethiopia (functional cosmetics), South Africa (under South African Bureau of Standards (SABS) standard), Australia (under standards) [16], and Taiwan (medicated cosmetics). In Canada, they can be either OTC drugs or natural health products (NHP), where in such a case the sunscreen agents should only be “natural” ingredients: titanium dioxide, zinc oxide [17]. Figure 21.1 Overlay of erythemal action spectrum and reference solar spectrum irradiance (ASTM G‐173) [2]. As of this writing, there are 16 UV filters approved for use in OTC sunscreen formulations in the United States (Table 21.1). In February 2019, FDA issued the proposed rule, Sunscreen Drug Products for Over‐the‐Counter Human Use in order to finalize the monograph of this product class [18]. The proposed rule included many changes to the existing stayed final monograph issued in 2011. Due to the overwhelming response from industry, professional organizations, physicians, various lobbying group, and concerned citizens, the FDA has delayed the implementation as of this publication date. The proposed changes to the status of currently approved UV filters are summarized below: There are two main regulatory routes to market OTC products in the United States: use of a UV filter included in the monograph or an new drug application (NDA). The latter is necessary to obtain the approval of a formula containing a new UV filter, a new concentration for an approved active ingredient, or a new mixture of approved actives. As an example, ecamsule is available in the United States under NDA for four formulas only. A time and extent application (TEA) is a procedure established by the FDA in 2002 to approve an active ingredient already approved abroad. It allows the FDA to accept commercial data obtained from markets outside of the United States. However, the toxicological data file required for a TEA is similar to that for an NDA. To date, eight UV filters have been submitted to the FDA under a TEA but all require additional safety and toxicological data in order to support inclusion in the monograph as Category I, i.e. GRASE. Table 21.1 Sunscreens approved in the USA. Figure 21.2 Common UV filters and spectral coverage. DHHB = diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate. In the EU, 27 UV filters are listed in Annex VII of the Cosmetics Directive. In Australia, 26 UV filters are accepted by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and in Japan 31 UV filters are allowed. When comparing the approved UV filters in EU and the United States, only 11 filters appear in common. Because of the importance of being well‐protected against UVA radiation, there are many new UVA filters or broad spectrum UVB/UVA filters, which have been developed and approved in EU, Australia, and Japan. See Figure 21.2 for a list of commonly used UV filters and their spectral coverage A proper sunscreen product must fulfill the following critical requirements: In order to protect against both UVB and UVA, the sunscreen product must contain a combination of approved UV filters within a complex vehicle matrix. According to their chemical nature and their physical properties, they can act by absorbing, reflecting, or diffusing UV radiation. Organic filters are active ingredients that absorb UVR energy to a various extent within a specific range of wavelengths according to their chemical structure [19], which, absorbing energy, is called a chromophore. The latter consists of electrons engaged into multiple bond sequences between atoms, generally conjugated double bonds. An absorbed UV photon contains energy enough to cause electron transfer to a higher energy orbit in the molecule [19]. The filter that was in a low‐energy state (ground state) is converted into a higher excited energy state. From an excited state, different processes can occur:

CHAPTER 21

Sunscreens

Introduction

Effect of sunlight exposure on skin

Regulatory status of sunscreens

Sunscreen classification

![Schematic illustration of overlay of erythemal action spectrum and reference solar spectrum irradiance (ASTM G-173) [2].](http://plasticsurgerykey.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/c18f001.jpg)

Approved UV filters

Sunscreen approved in the US

Maximum concentration (%)

λmax (nm)

Status

p‐Aminobenzoic acid (PABA)

15

283

Proposed Category II

Avobenzone

3

357

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Cinoxate

3

308

Proposed Category III. Industry will not support

Dioxybenzone

3

284 and 327

Proposed Category III. Industry will not support

Ensulizole (phenylbenzimidazole sulfonic acid)

4

310

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Homosalate

15

306

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Meradimate (menthyl anthranilate)

5

336

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Octinoxate (octyl methoxycinnamate)

7.5

311

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Octisalate (octyl salicylate)

5

305

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Octocrylene

10

303

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Octyl dimethyl PABA (padimate O)

8

311

Industry will not support

Oxybenzone (Benzophenone‐3)

6

286 and 324

Proposed Category III. Industry to support

Salisobenzone

10

285

Proposed Category III. Industry will not support

Titanium dioxide

25

280–350

Category 1 – GRASE

Trolamine salicylate

12

298

Proposed Category II

Zinc oxide

25

280–390

Category 1 – GRASE

Development of sunscreens

Organic UV filters

How do organic filters work?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree